by Jan Raska, PhD, Historian

(Updated July 13, 2020)

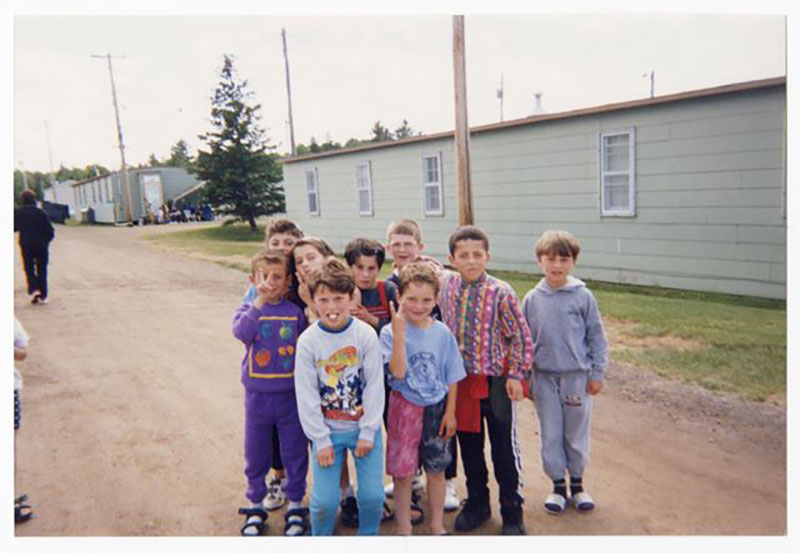

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2017.635.35)

Introduction: The Significance of the Kosovar Refugee Movement to Canada

In February 1998, widespread ethnic tensions in the Yugoslav province of Kosovo led to an outbreak of armed conflict between the forces of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY) and the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA). The conflict saw thousands of ethnic Albanians living in the province in fear of further ethnic cleansing seek refuge in neighbouring Albania and Former Yugoslav Republic (FYR) of Macedonia. Due to this large movement of people, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) appealed to the international community for political, financial, and logistical support. The UNHCR was concerned for the immediate protection of Kosovars who had sought safety and shelter outside of their homeland. For its part, the Canadian government offered to provide temporary safe haven for 5,000 Kosovar refugees. Once brought to Canada, the refugees would be permitted to apply for permanent resident status. In previous decades, the Canadian government resettled refugees in search of safe haven including some 37,500 Hungarians between 1956 and 1958, over 11,200 Czechs and Slovaks from 1968 to 1969, and approximately 60,000 Vietnamese, Cambodians, and Laotians, between 1979 and 1981. Following these important special programs for refugees, the Kosovar refugee movement set an important precedent: it marked the first time that the Canadian government participated in an emergency humanitarian evacuation program designed to provide temporary protection to vulnerable individuals fleeing from a place of mass exodus.[1]

The Kosovar refugee movement is significant in three notable ways: first, its duration was relatively short as thousands of refugees were brought to Canada in less than a month; second, the Kosovar movement was organized around sustainment centres on Canadian Forces Bases (CFBs), which provided accommodations and basic necessities to the refugees over several weeks; and third, Canadian officials resettled Kosovar refugees in Canada with the understanding that some of them might wish to be repatriated to Kosovo. Therefore, repatriation, as a final outcome, was included in the resettlement program.[2] This plan meets the conditions of the UNHCR’s “Durable Solutions” framework for refugee populations – in particular its three core tenets: voluntary repatriation, resettlement, and integration – which seeks to find workable resolutions to the plight of refugees and their families.[3]

Permanent Resettlement or Temporary Status for Kosovar Refugees

The origins of the Canadian government’s emergency humanitarian evacuation program for Kosovar refugees can be traced back to the UNHCR. The High Commissioner for Refugees, Sadako Ogata, lobbied national governments to help provide safe haven to approximately 350,000 individuals who fled Kosovo over a span of eleven days in March 1999.[4] After several failed attempts to reach a diplomatic solution that would prevent further displacement, ethnic cleansing, and regional instability, on 24 March, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) launched Operation Allied Force – an aerial bombardment of the FRY that successfully forced the removal of Yugoslav forces from Kosovo and thwarted the FRY from further exacerbating the refugee crisis.[5]

Initially, Canadian officials were cautious to bring Kosovar refugees to Canada. This was exemplified by the Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, Lucienne Robillard, who questioned why the Canadian government should not assist the Macedonian and Albanian governments rather than accept Kosovars into Canada. Several months earlier, Minister Robillard reviewed Canada’s refugee policy and concluded against temporary refugee protection status. This decision was consistent with previous determinations by the Canadian government which established a policy of permanent resettlement rather than temporary status for refugees. In a phone call with the minister, Citizenship and Immigration Canada’s (CIC) Director General, Refugees, Gerry Van Kessel, recalls that Minister Robillard agreed that it was preferable for Canada to provide financial assistance to FYR Macedonia and Albania rather than refugee resettlement. Despite this evaluation, CIC officials learned hours later that Prime Minister Jean Chrétien spoke with U.S. President Bill Clinton and agreed to accept 5,000 Kosovar refugees.

Despite past bureaucratic decisions, the policy surrounding the evacuation of Kosovar refugees remained unclear to Canada officials. In recalling the Kosovar movement, Van Kessel asserts that

…the evacuation of the Kosovars was a very political response that overrode the practical wisdom and experience of refugee experts. For Canada the policy issue remained unclear. The Kosovars were coming under temporary status, as officially the Kosovars would be returning to their homes as soon as possible. A policy to allow them to remain would play into the hands of [FRY President] Milosevic who wanted to rid Kosovo of its Albanian population. As Canada did not have a temporary status policy, this approach fitted badly within a permanent resettlement framework.[6]

The UNHCR’s proposed temporary resettlement of the Kosovars underscores the limitations of Canada’s resettlement-only policy. Further complicating matters was the reaction of the Macedonian government regarding the arrival of tens of thousands of refugees from Kosovo. Macedonian officials argued that the entry of these Albanian Kosovars threatened to destabilize a delicate ethnic balance between Slavs and Albanians in their country. Furthermore, the Macedonian president, Kiro Gligorov, demanded that the United Nations request assistance from the international community to relocate the Kosovar refugees.[7]

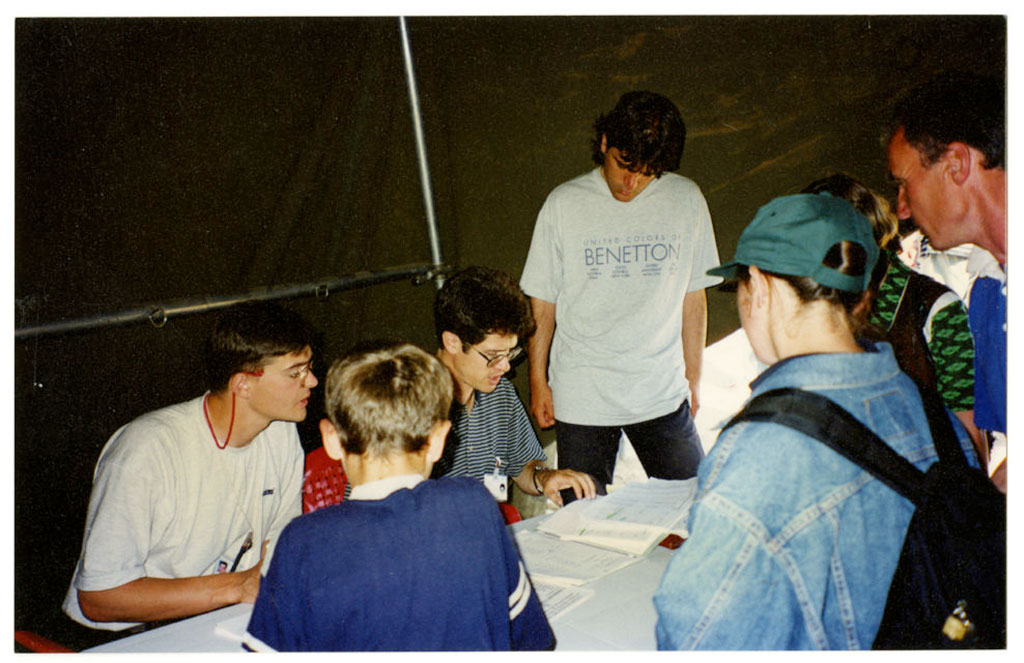

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2017.635.116)

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2017.635.110)

Operation Parasol: An Emergency Humanitarian Evacuation Program

On the following day, 4 April (Easter Sunday), Ottawa responded to the UNHCR by agreeing to evacuate 5,000 refugees. This number eventually grew to over 7,000 individuals. The Canadian government consolidated its efforts under a humanitarian evacuation program, “Operation Parasol,” which brought together federal government departments, provincial authorities, non-governmental organizations, and volunteers to help coordinate the resettlement of Kosovar refugees in Macedonian and Albanian camps to Canada. Soon thereafter, Canadian officials formed partnerships with the UNHCR and the International Organization for Migration (IOM). From within CIC, an official introduced procedures that had been developed two decades earlier during the resettlement of the Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Laotian ‘boat people’ to Canada.[8]

Essential to the success of Operation Parasol was the cooperation of the Department of National Defence (DND), which was called upon to provide temporary shelter for the refugees on military bases. In previous decades, the Canadian military had played a vital role in the resettlement of refugees and internally displaced persons, including the 1972 expulsion of Asians from Uganda.[9] Federal officials first requested the assistance of the DND on Easter Sunday and within the span of a few days were able to prepare and open previously unused military facilities. On 6 April, Canadian military authorities issued a Warning Order placing CFBs Borden, Kingston, Meaford, Petawawa, and Trenton in Ontario on 72 hours’ notice regarding the reception of some 5,000 Kosovar refugees. Meanwhile, Quebec City’s CFB Valcartier became a backup site. On 9 April, CFBs Aldershot, Greenwood, and Halifax in Nova Scotia, and Gagetown in New Brunswick were also included in the list of military sites participating in Operation Parasol. While CIC provided operational leadership, Canadian military authorities delivered logistical support including: transportation, shelter, food, and medical screening.[10] The Canadian Red Cross also played an important role as the organization believed the refugees should continue to receive assistance from an organization they were familiar with in Albania and FYR Macedonia. National Director of Disaster Relief and Prevention Services for the Canadian Red Cross, John Mulvihill, notes that “We were in Kosovo until the day before NATO took action.”[11]

At the time, Canada’s Ambassador to Yugoslavia and FYR Macedonia, Raphael Girard, informed High Commissioner Ogata that if the relocation of some Kosovar refugees was necessary, then they should be brought to neighbouring countries rather than relocated to overseas countries, such as Canada, Australia, and the United States, which had established policies of permanent resettlement rather than temporary relocation.[12] In the days following its initial appeal to the international community, the office of the UNHCR reassessed its need for overseas evacuation and instead turned its attention towards family reunification and persons with special needs. The UNHCR informed non-European member states that the situation on the ground was still volatile and that their assistance could still be required at a moment’s notice. The Canadian government decided to maintain a state of preparedness in order to help evacuate a large number of refugees (within three days) should the need arise. While many aspects of the Canadian government’s operation remained on standby, Canadian officials in the field began to fast-track the UNHCR’s priority cases, including people with urgent medical issues, at-risk and vulnerable individuals such as women and children, the elderly, babies, and persons with family members in other countries. The UNHCR informed Canadian officers that refugees could not be evacuated without their consent nor could families be separated, even if extended family members had to be accommodated, and that the refugees selected had to be registered and deemed fit to travel. With these requirements, Canadian officers began their pre-screening and selection work without sufficient infrastructure: no offices and no phones.[13]

Identification and Registration of Kosovar Refugees in Albanian and Macedonian Camps

On 10 April 1999, two CIC foreign service officers were sent to FYR Macedonia and worked in two refugee camps outside the capital, Skopje: Stenkovac 1 (Brazda) and Stenkovac 2. With the help of a Canadian officer already in the field, one of the officials was tasked with locating refugees named on Relative Identification forms provided by their Canadian relatives. Meanwhile, the other official worked alongside the UNHCR and the IOM to register Kosovar refugees in the camps and later helped the UNHCR select refugees for resettlement in other European countries. In Albania, Canadian officials found the local conditions to be more difficult than in FYR Macedonia. Michael Boekhoven, a CIC foreign service officer in Albania, notes that “Communication was difficult…Cell phones died around two o’clock in the afternoon…Moving the refugees required a lot of resources…Interviews could be very time-consuming where large families with many adults were involved, and might take anywhere from half an hour to an entire day."[14] By the end of April, the camps in FYR Macedonia were overcrowded with Kosovar refugees who were at risk of being forced to return to their homes. Recognizing that the situation was increasingly dire, the UNHCR requested the assistance of the American, Australian, and Canadian governments in evacuating the refugees overseas. Within three days of the UNHCR’s request, Canadian authorities, who had maintained a state of preparedness, responded by accepting the call for assistance.

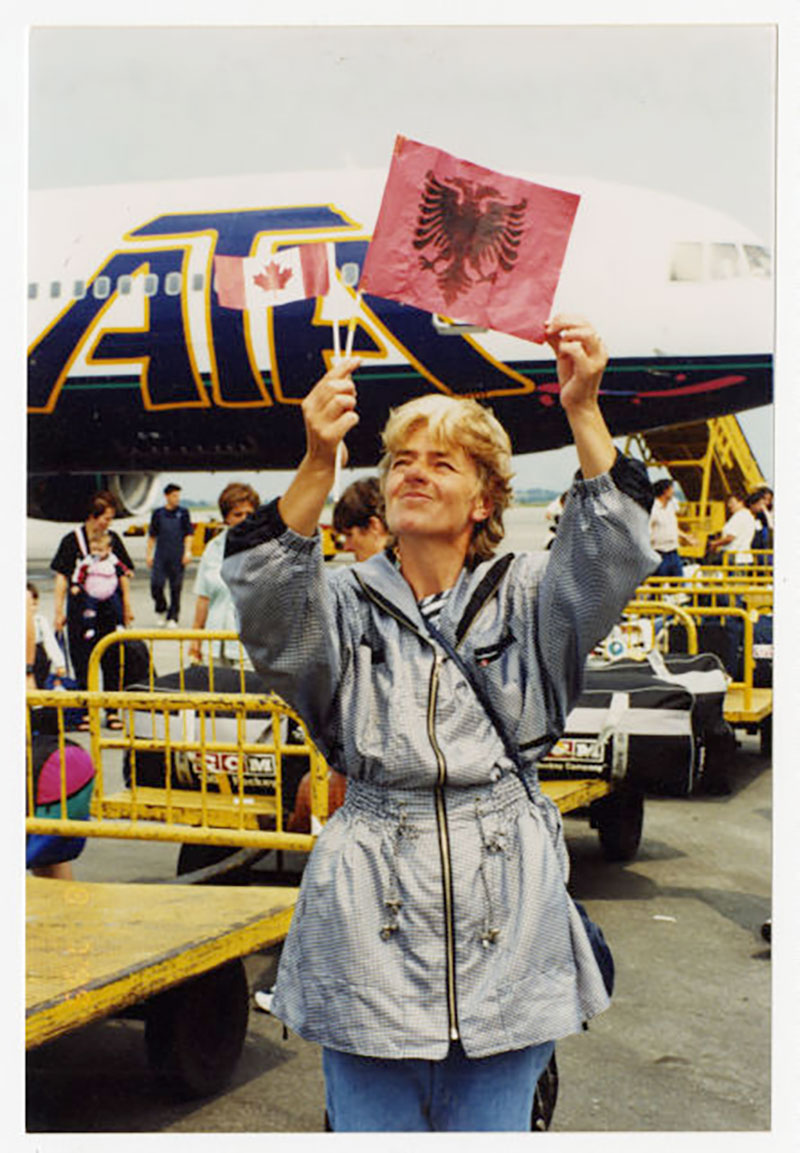

The Canadian government participated in this emergency evacuation program on the basis of providing refugees with temporary refuge. Canadian officials chose to provide the Kosovar refugees with temporary shelter in Canada, and they would be able later to apply for permanent residency. Canadian officials in the refugee camps of FYR Macedonia and Albania found that many of the Kosovar refugees were reluctant to resettle in Canada.[15] Some of the refugees believed that Canada was too far away and too cold for a successful resettlement. They sought to stay relatively close to their homeland and awaited a possible return to their homes. Despite these perceptions of Canada, the Kosovar refugees who had resided in the camps the longest were often the most willing to be resettled overseas. Canadian officers in the field implemented a system to fill each day’s charter flight to Canada. Once the list of refugees registered in each camp had been computerized, it was then posted across the camp. Heads of families were requested to visit the Canadian tent with their documents to confirm whether they wished to be resettled in Canada. A flight manifest and standby list were prepared daily in order to fill each aircraft. Subsequently, the IOM was responsible for making all the transportation arrangements and the refugees were brought to Canada aboard the former Canadian carrier, Royal Airlines.[16]

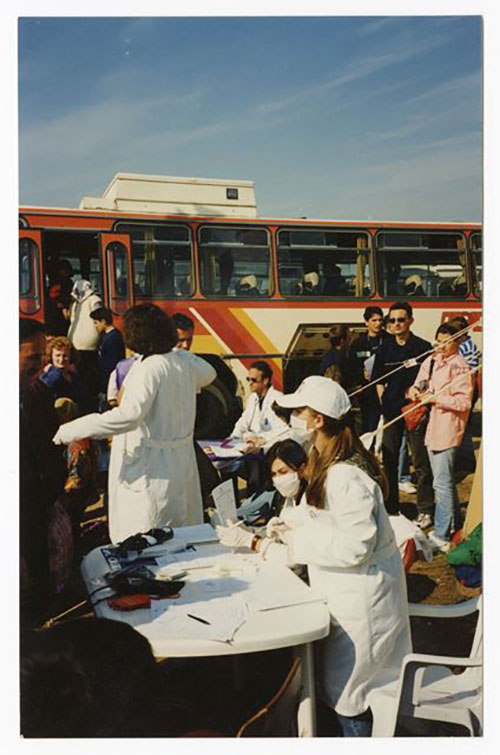

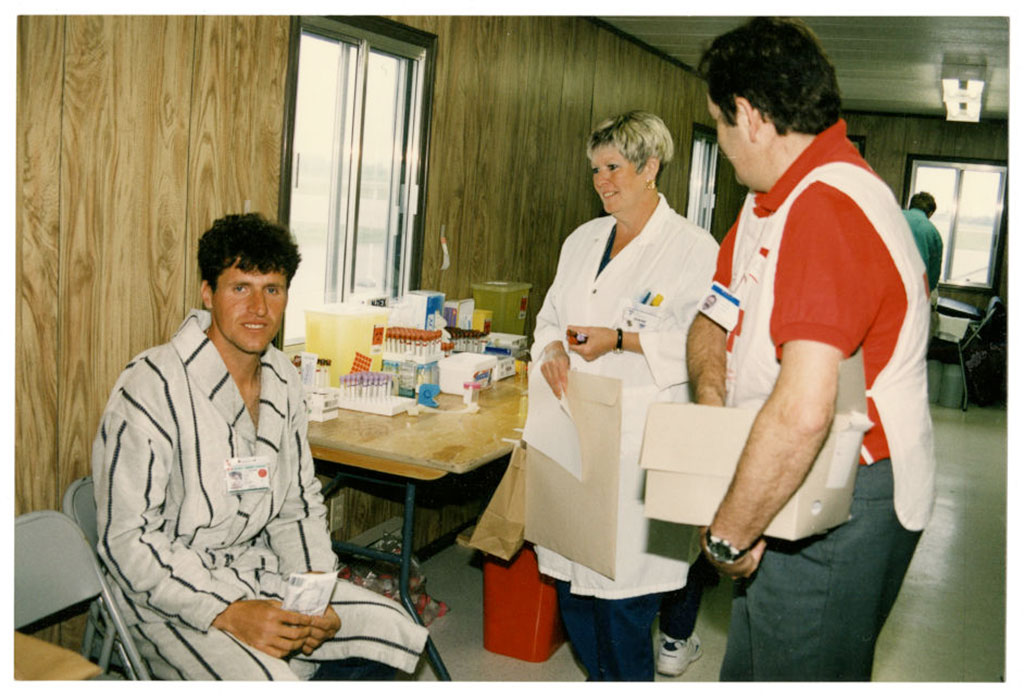

“Fit to Fly”? Medical Screening before Departure for Canada

Before a Kosovar refugee boarded a flight, Canadian doctors had to determine whether they were “fit to fly.” Each person was given a colour-coded identification: ‘red’ indicated persons in need of immediate medical attention upon arrival in Canada, ‘yellow’ specified individuals with potential problems that would require assistance soon after arrival, and ‘green’ designated persons who could wait until the following day, after arrival, to see a doctor. Medical information was faxed from the camps to reception centres at CFBs Trenton and Greenwood where medical staff could prepare for their arrival. Among the refugees brought to Canada, few serious medical issues were reported. Only 1 percent of the refugees were coded ‘red,’ 5-6 percent were coded ‘yellow,’ and the remainder were coded ‘green.’ The Kosovar refugees were briefed during their bus rides to the airport about resettlement in Canada and acquiring employment, but most individuals did not want to hear this information, opting instead to focus on a return to Kosovo. Boekhoven notes that “Many spoke very forcefully about their desire to return to their country…They are very tied to the land and the extended family.”[17]

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2017.827.47)

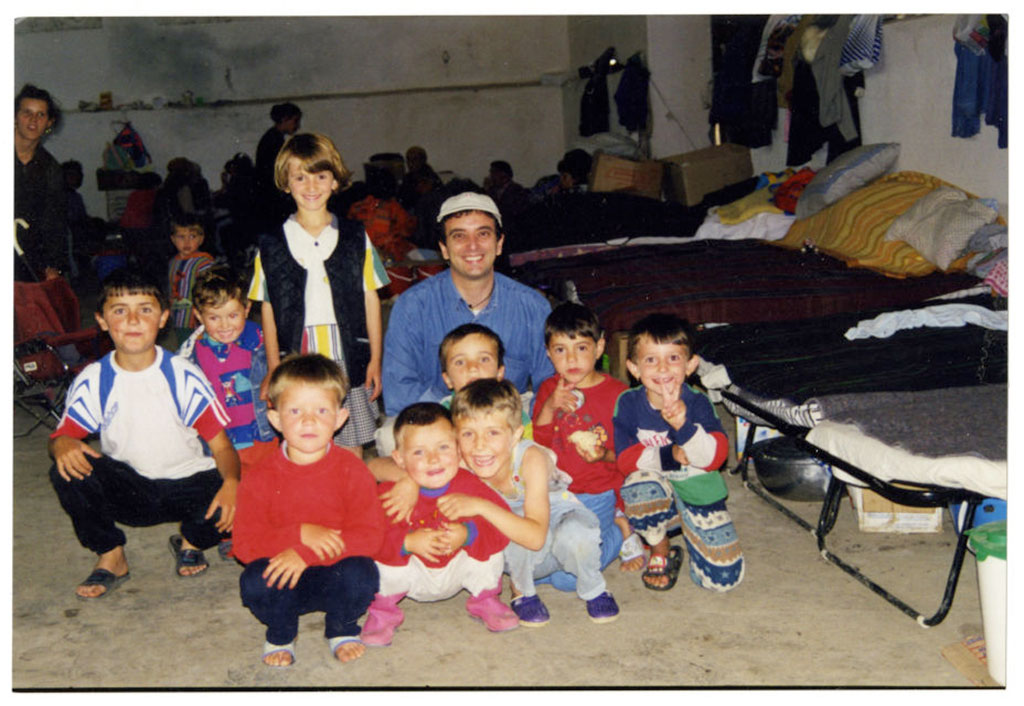

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2017.827.40)

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2017.635.127)

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2017.827.45)

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2017.827.52)

Kosovar Refugees Arrive in Canada

On 27 April 1999, two Kosovar families arrived in Toronto and were greeted by Minister Robillard.[18] They were the first refugees to arrive in Canada under the accelerated Kosovo Family Reunification program (KOF).[19] A few days later, on 4 May, the Humanitarian Evacuation program’s (KOS) first flight arrived at CFB Trenton in Ontario. The chartered flights alternated between CFBs Trenton and Greenwood in Nova Scotia. In total, twenty-one flights brought over 7,000 Kosovar refugees to Canada, with arrivals occurring almost on a daily basis.[20] Only nine years old when he landed at CFB Greenwood, Kushtrim Vuniqi remembers that “…the airplane doors opened, I could see a crowd of people waiting with teddy bears and Canadian flags, cheering. I had a warm feeling and happiness, I felt like a child again.”[21] On 26 May, the last evacuation flight arrived in Canada. Over 90 percent of the refugees were received at CFBs Trenton and Greenwood. The Canadian government brought 5,051 Kosovar refugees to Canada under the KOS (Operation Parasol), and a further 2,292 were admitted into the country under the KOF, which continued for several months after the end of the evacuation.[22]

As the refugees disembarked from their flights at CFB Trenton, they were welcomed by Minister Robillard, the UNHCR representative in Canada, Yilma Makonnen, and the President of the Canadian Red Cross, Gene Durnin. Afterwards, immigration and customs officers, military personnel, medical officers, and Red Cross workers greeted the refugees. At CFB Trenton, the Kosovars arrived around 5 p.m. every other evening. Medical staff quickly conducted an “airport triage” for each group of arrivals based on the colour-coded list faxed to them from FYR Macedonia and Albania. There were 1-4 individuals identified as “red” on each arriving flight. They were sent by ambulance to a nearby hospital in Belleville. Due to the long journey, dehydration was common among the refugees, and in some cases, this worsened health conditions. One 94-year-old woman suffered heart failure after disembarking from her plane and was sent immediately to Belleville General Hospital where, after a few days, she made a healthy recovery. Those refugees deemed to be “yellow” or in need of limited care were also tended to by Canadian military medical officers.[23]

Processing Kosovar Refugees upon Arrival in Canada

In order to effectively process the refugees, Canadian officials implemented escort teams, comprised of a military member and a volunteer, who were assigned to a group of seven to fourteen refugees. The groups were to consist of entire families, including pets, to ensure that no one was left behind or became lost. Each escort team was responsible for knowing the whereabouts of each refugee in their group and for their movement through each station: immigration, medical screening, identification, showering, meals, and clothing and shoe distribution. Each refugee received three sets of clothing and new shoes. An important component of processing the refugees was the latter station, often referred to as “the shoe store.” This station fitted the refugees with proper shoes and exchanged footwear deemed by Canadian officials to be “agriculturally unsound” or too dirty to clean. In effect, footwear brought to Canada could have contained organic materials, such as foreign soil, and was considered harmful and even dangerous to Canadian agriculture. Such items were confiscated and later incinerated. Similarly, Canada Customs officers inspected baggage and confiscated any prohibited items such as food. Altogether, the entire reception process lasted less than an hour.[24]

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2017.827.11)

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2017.635.61)

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2017.827.7)

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2017.635.76)

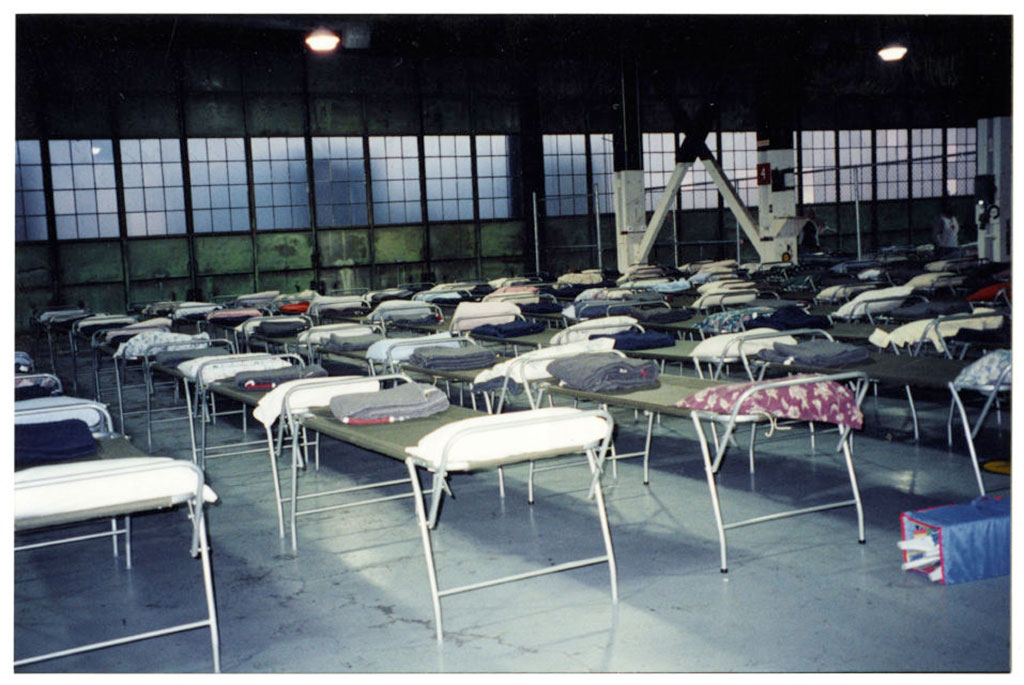

On the first evening of the emergency evacuation program, 550 meals were served to refugees, volunteers, and staff. Children received “Zeddy Bears” courtesy of former Canadian department retailer, Zellers. At CFB Trenton, the refugees were bused to nearby CFB Mountain View where large hangars were ready to receive them. A “medical mall” consisting of a “cluster of 8 trailers, some tents and 2 World War hangars, all joined together by plywood tunnels” served as initial accommodations for hundreds of Kosovar refugees during their first night in Canada. It was also the centre of medical examinations for all Kosovars arriving in Ontario. After their first night of rest, the following morning, the refugees began their medical examinations at 7 a.m. and the process took 2 or 3 hours to get through the “medical mall.” Reminiscent of the support provided by the Canadian Armed Forces in screening arriving Ugandan Asians at CFB Montreal (Longue-Pointe) in 1972, processing an entire planeload of arrivals took approximately 12 to 16 hours. At Mountain View, the Kosovars received an identity card, and were sent to the medical wing which housed examination rooms that had portable X-ray machines, a pharmacy, and bathrooms. The refugees were examined and received vaccinations. Each flight required the services of approximately a dozen doctors.[25] CIC’s on-site manager, Doug Corrigan, remembers that…

Their medical condition really surprised me…They were very fragile. They’d be fine one minute, but after they got through the medical wing, they sometimes had to be taken to the hospital…The whole Mountainview experience was really challenging…We worked long hours into the night with the military, the Red Cross, Health Canada, local and provincial authorities – everybody to make sure all the mandates were respected. We had to move people through that process within 24 hours in order to clean up and prepare for the arrival of the next flight.[26]

From Reception Centres to Sustainment Sites: Kosovar Refugees Receive Accommodations

Once the Kosovar refugees had been processed by Canadian officials, military authorities, and the Canadian Red Cross, they were sent to “sustainment sites” at other military bases. These sites provided accommodations to the refugees for their first eight to twelve weeks in Canada. Afterwards, the Kosovar refugees would be placed with private sponsors across Canada. As CIC’s Director of Resettlement, Rick Herringer was responsible for managing and coordinating Operation Parasol for the Canadian government. He notes that “Our past experience with the Indochinese and Bosnian refugees indicated that the best way to assist the refugees was by working with local communities and organizations. The one difference with the Kosovo program was that the newcomers stayed longer (several weeks) at the sustainment sites before being moved.” In the case of the Indochinese movement (1979-1981), refugees stayed at reception centres for only two or three days before their placements with private sponsors.[27] Nevertheless, the Kosovars’ prolonged accommodation at the sustainment sites was warranted. Ismael Aquino, a trained nurse who worked for the Canadian Red Cross in Nova Scotia, describes welcoming the Kosovar refugees at CFB Greenwood…

Well, part of it was to receive them and make sure that they were being taken care of. Because they were going to be processed…medically through…[the] airport in Greenwood….they needed to be settled into sustainment sites, so we want to make sure they had all their needs taken care of, and dealing with things like, translation, making sure that they were getting to medical appointments, you know, and the psycho-social support because some of the refugees would have experienced some, a lot of traumatic things in the…conflict…And many of them…were exposed to…some traumatizing scenarios…[28]

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2017.827.5)

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2017.827.4)

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2017.827.3)

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2017.827.8)

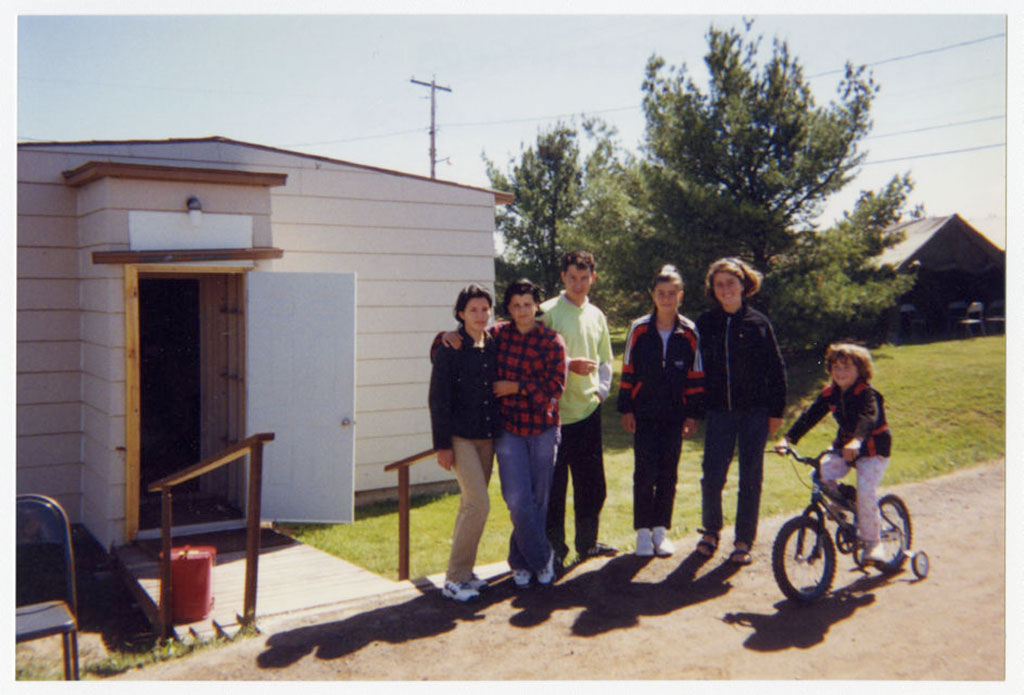

The Kosovar refugees at CFBs Trenton and Mountain View were brought to CFBs Kingston and Borden in Ontario, while those who arrived at CFB Greenwood were brought to CFB Aldershot and CFB Halifax in Nova Scotia, and CFB Gagetown in New Brunswick. Within the confines of the military base at Gagetown, the Kosovar refugees were housed at a training complex for Army cadets known as Argonaut Army Cadet Summer Training Centre.[29] Following their arrival at the various sustainment sites, the Kosovar refugees could access medical clinics, dining facilities, laundry rooms, recreational and child care facilities, and shops for basic necessities. Canadian immigration officers finalized the interview process with each family. The refugees received Minister’s permits in order to enter the country, employment and student authorizations, a health card, and a Social Insurance Number.

Providing Language and Settlement Support to Kosovar Refugees

Each refugee family was then matched with sponsors across Canada. Each military base required approximately 40-50 interpreters who could understand Albanian and could also assess the refugees’ level of English- and French-language competency. Once the Kosovar refugees had been successfully processed, many began to take language courses. Children occupied their time playing, while older women joined knitting clubs. Known as the unofficial mayor of the Kosovar refugee camp at CFB Trenton, Muharrem Krasniqi states that “The conditions we have been offered here are five hundred times better than those of the Stenkovac camp.”[30] Meanwhile, twenty-one-year-old Alba Rahmani, from Kosovo’s capital, Pristina, worked as an interpreter for Canadian immigration officials and asserts “I can’t believe how kind Canadians are. Everybody is always smiling.”[31]

In Nova Scotia, the Metropolitan Immigrant Settlement Association (MISA), a predecessor of the Immigrant Services Association of Nova Scotia (ISANS), was contracted by CIC to provide Kosovar refugees with on-site settlement support at military bases across the province. From 5 May to 5 August 1999, MISA employed four staff members at Camp Aldershot, five employees at Windsor Park (CFB Halifax), and three replacement staff for the organization’s Settlement unit. Personnel assisted recently-arrived refugees with cultural orientation and played an important role in bridging any gaps between local partners – who may have had no experience in refugee resettlement – and the refugees themselves. MISA provided individual and group meetings, informal drop-in sessions, and helped to publish an Albanian-language newsletter for new arrivals. [32]

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2017.827.18)

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2017.827.16)

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2017.827.28)

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2017.827.33)

Appeal for Sponsors

In May 1999, Minister Robillard and refugee-serving organizations appealed to sponsors for help in permanently resettling refugees in communities across Canada. CIC officials decided that the Joint Assistance Sponsorship (JAS) program would best enable the Kosovar refugees to recover from their traumatic experiences overseas. The JAS program provided two years of financial assistance from the Canadian government and moral support and friendship from groups of Canadians who had agreed to sponsor a refugee or refugee family. Existing Albanian communities across Canada also provided support. Sponsors could be affiliated with a Sponsorship Agreement Holder, such as a church or community organization, or could form groups of five or more Canadians with the support of an association to privately sponsor a refugee family. While provincial authorities agreed to take their share of Kosovar refugees, federal officials were surprised by the number of private sponsors who offered their support. CIC officials believed that they required approximately 1,200 to 1,400 sponsors; however, they received interest from some 1,700 sponsors.

A day later, Prime Minister Chrétien, Minister Robillard, and Secretary General of the Canadian Red Cross, Dr. Pierre Duplessis visited the Kosovar refugees housed at CFB Borden. They were impressed with the large number of volunteers working with the refugees. The Canadian Red Cross was responsible for coordinating volunteers, organizing activities, and collaborating with donors. Organized activities included a Blue Jays game for the refugees housed in Trenton and a city tour for those residing in Kingston. Donations to the Red Cross included toys, bicycles, clothing, and services – including a boat cruise of the Thousand Islands, and cosmetic facials for 200 women.[33]

After the Peace Agreement: Permanent Resettlement or Repatriation?

Following the 10 June 1999 peace agreement between the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) and Yugoslav authorities, thousands of Kosovars who had fled their homeland in search of refuge elsewhere began to return home. Soon, this news reached Kosovar refugees in Canada. The first repatriation flight to leave Canada departed on 7 July, bound for Skopje, FYR Macedonia. Despite the interest of some of the refugees to return home, by 2001, Canadian officials had noted that nearly 70 percent of the Kosovars had decided to resettle permanently in Canada. On 31 August 1999, following the successful reception of the Kosovar refugees in Canada, federal officials terminated Operation Parasol, while the family reunification program concluded a few months later.[34]

In recalling his experiences of helping resettle Kosovar refugees, Ismael Aquino asserts that Canada’s reception of Kosovar refugees “…was a—real eye-opener in terms of recognizing those who were vulnerable even in other countries, having to come to Canada…for safety…” Many of the Kosovars settled across Canada, but a few chose to reside in Nova Scotia. Aquino recalls getting reacquainted with a Kosovar refugee who arrived at the age of twelve. Now 27 years of age, she settled in Canada and had two children.[35] According to the Albanian Canadian Community Association of Nova Scotia, nearly 200 Kosovar refugees permanently settled in the province. However, language barriers, a lack of favourable employment, and a desire to live near other Kosovar refugees forced many to seek opportunities in other parts of Canada.[36]

Conclusion

According to CIC officials, the Kosovar movement demonstrated that Canadian officials, humanitarian organizations, and community groups could collaborate effectively for a common cause – the evacuation, resettlement, and integration of refugees in Canada.[37] In recalling his experiences during the Kosovar refugee crisis, Canada’s former Ambassador to Yugoslavia and FYR Macedonia, Raphael Girard, recognizes that the Canadian government had no means of providing temporary assistance except through its refugee resettlement program. Therefore, the 1999 Humanitarian Evacuation program (KOS) or Operation Parasol is “…the exception that proves the rule.”[38]

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2017.827.36)

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2017.827.37)

- Valerie Knowles, Strangers at Our Gates: Canadian Immigration and Immigration Policy, 1540-2015 (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2016), 245. Canada participated in the larger Kosovo crisis as a member of the United Nations Kosovo Force (KFOR) by providing pilots that flew combat missions over FRY and deployed troops and tanks. Canada’s military deployment to the Balkans was its largest since the Korean War (1950-1953). See Canada, Department of National Defence (hereafter DND), “Kosovo Force (KFOR),” last modified 11 December 2018, https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/services/military-history/history-heritage/past-operations/europe/kinetic.html; Veterans Affairs Canada, “Historical Sheet – The Canadian Armed Forces in the Balkans,” last modified 14 February 2019, https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/history/canadian-armed-forces/balkans/information-sheet-balkans.↩

- Michael J. Molloy, “The Kosovar Refugee Movement: Introduction,” CIHS Bulletin 48 (April 2006): 7. See the Canadian Immigration Historical Society’s website, http://cihs-shic.ca/bulletin/.↩

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Framework for Durable Solutions for Refugees and Persons of Concern, May 2003, https://www.refworld.org/docid/4124b6a04.html. See page 11 of document. When “Durable Solutions” are not achievable, the UNHCR seeks to secure “complementary pathways for admission to third countries” for refugees.↩

- Pamela Currie, “Kosovo: A unique humanitarian experience for Canada,” Vis-à-Vis: The CIC Magazine (Summer/Fall 1999): 4.↩

- DND, Directorate of History and Heritage (hereafter DHH), “Details/Information for Canadian Forces (CF) Operation PARASOL,” last modified November 28, 2008, http://www.cmp-cpm.forces.gc.ca/dhh-dhp/od-bdo/di-ri-eng.asp?IntlOpId=196&CdnOpId=236.↩

- Gerry Van Kessel, “The Kosovar Refugee Movement: Comments 1: as seen by a participant,” CIHS Bulletin 48 (April 2006): 10.↩

- Raphael Girard, “The Kosovar Refugee Movement: Comments 2: Policy context,” CIHS Bulletin 48 (April 2006): 11. See also, Patrick Quinn, “Macedonia Won’t Accept Refugees,” Associated Press News, April 3, 1999, https://apnews.com/0aec17159895c77a79a0c46d5303eadb.↩

- Currie, “Kosovo,” 4.↩

- For context, see “Op Parasol,” Canadian Forces Logistics Association, 2019, https://www.cfla-alfc.org/stories/op-parasol/; Canadian Armed Forces and Kelsey Berg, “Canadian Armed Forces: Logistical; Leaders in Resettlement,” NATO Association of Canada, 23 April 2016, http://natoassociation.ca/canadian-armed-forces-logistical-leaders-in-resettlement/. Canada permanently resettled close to 8,000 Ugandan Asians between 1972 and 1974.↩

- DND, DHH, “Details/Information for Canadian Forces (CF) Operation PARASOL.”↩

- Currie, “Kosovo,” 6.↩

- Girard, “The Kosovar Refugee Movement: Comments 2: Policy context,” 11↩

- Currie, “Kosovo,” 6.↩

- Currie, “Kosovo,” 8.↩

- Canadian officials could refer to an earlier precedent. Between September 1992 and August 1994, Canadian officials evacuated 10 medical patients and their family members from the territories of the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. For further context, see Jacqueline Weekers, Paola Bollini, Harald Siem, and Barbara Dean, “Medical Evacuations from the Region of Former Yugoslavia,” European Journal of Public Health 6.4 (December 1996): 257-261.↩

- Currie, “Kosovo,” 10, 12.↩

- Currie, “Kosovo,” 12.↩

- Book of newspaper clippings titled, Memories of Kosovo, ca. 1999. Canadian Museum of Immigration (hereafter CMI) Collection (D2017.902.5). See Citizenship and Immigration Canada, news release 99-22, “Minister Lucienne Robillard Welcomes Refugees from Kosovo.” Before the families and gathering media, Robillard declared “I am pleased, on behalf of all Canadians, to welcome this refugee family coming to Canada from Kosovo. Being with their loved ones in Canada will give them the support they need in these difficult times.”↩

- Kosovo refugees arrive in Canada,” CBC News, April 27, 1999, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/kosovo-refugees-arrive-in-canada-1.194436.↩

- Currie, “Kosovo,” 14; Knowles, Strangers at Our Gates, 245-246.↩

- Arta Rexhepi, “‘We will always be grateful:’ Kosovo refugees reflect on how Canada shaped their lives,” CBC News, June 17, 2019, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/kosovo-refugees-anniversary-greenwood-1.5156189.↩

- Currie, “Kosovo,” 14; Knowles, Strangers at Our Gates, 245-246; DND, DHH, “Details/Information for Canadian Forces (CF) Operation PARASOL;” “The Kosovar Refugee Movement,” CIHS Bulletin 48 (April 2006): 12.↩

- Currie, “Kosovo,” 14, 16; Barbara Sibbald, “Canada’s Kosovar refugees ‘Surprising healthy,’” Canadian Medical Association Journal 160.12 (15 June 1999): 1755.↩

- DND, DHH, “Details/Information for Canadian Forces (CF) Operation PARASOL”; Currie, “Kosovo,” 14, 16.↩

- Currie, “Kosovo,” 14, 16; Sibbald, “Canada’s Kosovar refugees ‘Surprising healthy,’” 1755.↩

- Currie, “Kosovo,” 14, 16.↩

- Rick Herringer, “The Kosovar Refugee Movement: Speaking Notes for the Kosovo Seminar, Geneva, 2002,” CIHS Bulletin 48 (April 2006): 8.↩

- Oral History with Ismael Aquino, interviewed by Lindsay Van Dyk, Halifax, 7 November 2014, CMI Collection (14.11.07), 00:10:03. Aquino and his family immigrated to Canada from the Philippines in 1969. Today, he serves as the provincial director of the Red Cross in Nova Scotia.↩

- “Argonaut Cadet Training Centre,” Army Cadet History.↩

- Currie, “Kosovo,” 16.↩

- Currie, “Kosovo,” 16.↩

- “Looking Back: Operational Parasol – Canada responds to Kosovar refugee crisis,” Immigrant Services Association of Nova Scotia (ISANS), 18 August 18, 2015, https://www.isans.ca/looking-back-operation-parasol-canada-responds-to-kosovar-refugee-crisis/.↩

- Currie, “Kosovo,” 18.↩

- Currie, “Kosovo,” 20; “Op PARASOL.”↩

- Oral History with Ismael Aquino, 00:10:03.↩

- Rexhepi, “‘We will always be grateful.’”↩

- Currie, “Kosovo,” 20.↩

- Girard, “The Kosovar Refugee Movement: Comments 2: Policy context,” 11-12.↩