by Jan Raska, PhD, Historian

(Updated October 16, 2020)

Introduction

In January 1971, the Ugandan government of President Milton Obote was overthrown in a coup d’état by the Ugandan military under the leadership of General Idi Amin. The Asian Ugandan community was initially relieved by Amin’s seizure of power since Obote’s socialist government had planned to take a 60 percent stake in the country’s Asian-owned businesses.[1] On 4 August 1972, President of Uganda, Idi Amin, ordered the expulsion of the country’s Asian population. Claiming that he had received an order from God, Amin gave Ugandans of Asian heritage ninety days to leave the country.

At the time, there were more than 80,000 Asians in the country, mostly of Indian or Pakistani origins.[2] Fearing for their personal security and those of their relatives, over 27,000 Ugandan Asians fled to Great Britain, and more than 6,000 departed for Canada in late 1972. This important movement of refugees from Uganda was one of the earliest programs to resettle non-Europeans in postwar Canada and as such, a significant milestone in the history of refugee settlement in Canada.[3] The first non-European refugees to be selected overseas and resettled in Canada were 76 Palestinian refugees in 1956, and 100 Chinese families from Hong Kong in 1962.[4] Seven years after the arrival of the Chinese refugees, Canada ratified the 1951 United Nations Convention relating to the Status of Refugees in 1969. A year later, the federal Cabinet directed that the refugee convention be used to select refugees and simultaneously adopted an “Oppressed Minority” policy which permitted the resettlement of oppressed individuals who did not fit the UN refugee convention definition because they had not fled their homeland. The policy proved useful in resettling refugees in the early 1970s.[5] The 1972 expulsion of the Ugandan Asians, followed a year later by the 1973 Chilean crisis, illustrated to Canadian officials that refugee resettlement programs would remain a necessity within Canadian immigration policy. As a result, the selection and resettlement of over 6,000 Ugandan Asians during 1972-1973 paved the way for future refugee programs including the admission of over 77,000 Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Laotian ‘Boat People’ between 1975 and 1981.[6]

Canadian Officials Respond to the Expulsion of the Ugandan Asians

The news of the expulsion of the Ugandan Asians was met with considerable interest across the world. Along with Canada, Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Italy, Australia, and the United States were all willing to grant the Ugandan Asians asylum.[7] In Canada, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau immediately established a taskforce to coordinate his government’s response to the crisis. Many of the Ugandan Asians carried British passports and sought to begin new lives in the United Kingdom. While British officials worked quickly to process applications for resettlement, some Ugandan Asians were soon disappointed with the reception they received from the British consular staff. For example, Jalal Jaffer, a Ugandan Asian refugee who resettled in Vancouver recalls that...

You may line up for five hours and then by the time you get anywhere near they say ‘Oh no, it’s closed now. Come tomorrow.’ So people were really, really completely shattered...when you treat people like animals, they start behaving like animals.[8]

On 18 August 1972, the British High Commission appealed to Western countries for assistance in getting the Ugandan Asian population out of the country. During discussions, the Canadian government expected many Ugandan Asians to meet the admission standards under Order-in-Council P.C. 1967-1616 (commonly referred to as the 1967 points system) but were aware that this would not be sufficient since processing individuals and families could take a significant amount of time. As a result, Canada announced that it would send an immigration and medical team to Kampala to process the applicants for resettlement. At the time, Trudeau stated that "this step will enable us to form a clearer impression of the numbers involved and of the extent to which exceptional measures may have to be taken to deal urgently with those who would not normally qualify for admission."[9]

Canada Sends an Immigration and Medical Team to Kampala to Select Prospective Immigrants

With a federal election looming and increasing public concern over high unemployment, Minister of Manpower and Immigration, Bryce Mackasey, was limited in the number of individuals that his department would be permitted to resettle. Mackasey had previously urged for a more considerable limit of 8,000 Ugandan Asians. A compromise of 6,000 persons was eventually agreed upon by the federal Cabinet. The Canadian government moved slowly sensing “marked public opposition to the exercise and fearing a backlash if the Asians were granted special concessions.”[10] With no facilities in Uganda, immigration officials and government doctors arrived to select prospective immigrants. Within six days, Canada had established an office full of immigration officers, visa typing specialists, and Health Canada doctors to examine the applicants.[11] The Canadian office opened its doors on 6 September 1972 to a lineup of applicants that spanned ten blocks. Jalal Jaffer remembers that...

The Canadian government had sent in a small team to help the British by taking in some of the refugees and the experience at that office was markedly different… They provided chairs on the street so the people lining up in the hot sun could sit down and even served them water...[12]

Immigration officer Mike Molloy noted that in late September 1972 two instances shaped the character of the program. First, followers of deposed President Milton Obote staged a failed invasion which led to bloodshed and a general deterioration of army discipline. Second, Amin ordered Asians with Ugandan citizenship to report to have their citizenship confirmed. This ploy permitted the military to seize the documents of those who had followed instructions to report.[13] As a result, thousands of Ugandan Asians were rendered stateless. The Ismaili Muslim community, which made up 30 percent of the Asian community in Uganda that had previously opted for Ugandan citizenship, rather than remain British citizens after Ugandan independence, were hard hit by the loss of citizenship.

Canadian Officials Urged to Use “Humanitarian Considerations” to Resettle Desirable Applicants

Canadian officials believed that the highly educated and multilingual Ugandan Asians would meet the requirements of the points system, but were hesitant to solely depend on this piece of legislation to admit the Ugandan Asians to Canada. As a result, Canadian officials in Kampala were urged by Ottawa to use “humanitarian considerations” in an effort to resettle desirable applicants who might not otherwise be admitted into Canada. Seven airplanes were fully loaded with selected applicants and departed the week of 22 October. Another ten charters departed Kampala for Canada during the week of 29 October. With the expulsion deadline of 6 November fast approaching, Canada granted 6,175 visas to 2,116 families. In all, thirty-one charters carrying 4,426 individuals left Uganda for Canada. Later, another 1,725 Ugandan Asian refugees decided to find their own way to Canada on commercial flights from the United Kingdom and other countries in which they had been stranded after their expulsion. Three days after the Ugandan expulsion deadline of 6 November 1972, Canadian officials emptied their office and departed for home.[14]

Resettlement of Ugandan Asian Refugees in Canada

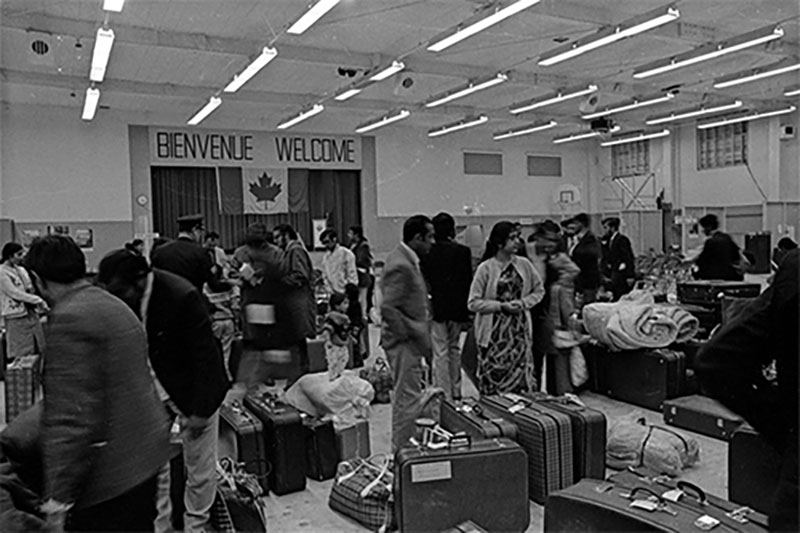

Many of the Ugandan Asians that Canada selected for resettlement had university degrees from England. Ginette Leroux, a Canadian visa worker, helped hand out over 2,600 immigration applications during her four weeks in Kampala. Leroux recalls that “they were very pleasant people and they were very educated people. I think we were lucky to get them … I think as far as immigrants and immigration goes, we got the cream of the crop.”[15] Most of the Ugandan Asian refugees arrived at Montreal, and were temporarily accommodated at Canadian Forces Base Longue Pointe, where they were interviewed, fed, and given information about resettlement in Canada. Other Ugandan Asians flew to Toronto where the next morning they were taken to Ontario House, a reception centre where they were given coffee and winter clothes.[16]

Immigration officials went about sending individual refugees and families to cities across the country. In many cases, the refugees were resettled in cities where they had friends, family, or business contacts. Eleven committees including national, provincial, and municipal representatives were established to assist the refugees during their initial resettlement.[17] By the end of 1973, more than 7,000 refugees were resettled in Canada.[18] Officials in Ottawa were quick to assist in resettling a further 2,000 Ugandan Asians who had become stateless during the 90-day eviction period, many of whom thought they had successfully requested Ugandan citizenship after independence from Great Britain in 1962. With no passports, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees temporarily sheltered the refugees in Spain and Malta before Canadian officials permanently resettled them.[19] In a follow up interview a year after their arrival, 89 percent of Ugandan Asian respondents who wished to be employed had found work, and 90 percent of respondents intended to permanently stay in Canada.

Conclusion

In 1970, the federal Cabinet directed that the recently signed UN refugee convention be used to select refugees for resettlement to Canada. The federal Cabinet simultaneously adopted an “Oppressed Minority” policy that permitted for the resettlement of individuals who did not meet the UN definition of a convention refugee, because they had not fled their homeland. The policy was used in the fall of 1972 when over 80,000 Ugandan Asians were expelled by President Idi Amin and given 90 days to leave the country. Ultimately, thirty-one charters carrying 4,426 individuals left Uganda for Canada. Later, another wave of 1,725 individuals boarded commercial flights destined for Canada. The federal government successfully resettled over 7,000 Ugandan Asians in 1972-1973. The 1972 expulsion illustrated that refugee resettlement programs would remain a necessity in future Canadian immigration policy.

Credit: Library and Archives Canada, accession no. NPC, archival reference R112-5134-4-E, item no. IM72-162

- Tara Carman, “‘We did it the Canadian Way’: A dedicated team of Canadians brought to safety almost 6,000 Asians kicked out by Idi Amin,” Vancouver Sun, 29 September 2012, E2.

- Mike Molloy, “Molloy: Reflecting on the Ugandan refugee movement,” Western News, http://news.westernu.ca/2012/10/molloy-reflecting. The Asian community consisted of Gujarati Hindus (50 percent), Ismaili Muslims (30 percent), with the remaining 20 percent divided between Sikhs, Goans, Punjabi Hindus, Ithnasharis, Boras, and a few Parses.

- Laura Madokoro, and Mike Molloy, “Remembering Uganda,” Active History, http://activehistory.ca/2012/03/remembering-uganda/.

- David Scott Fitzgerald, and David Cook-Martín, Culling the Masses: The Democratic Origins of Racist Immigration Policy in the Americas (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014), 181; Jan Raska, “Forgotten Experiment: Canada’s Resettlement of Palestinian Refugees, 1955-1956,” Histoire sociale / Social History 48.97 (November 2015): 445-473.

- Molloy, “Molloy: Reflecting on the Ugandan refugee movement.”

- Madokoro and Molloy, “Remembering Uganda.”

- Mobina Jaffer, “Expression of Thanks,” http://mobinajaffer.ca/senate-chamber/senate-chamber-statements.

- Tara Carman, “Shamshad and Jalal Jaffer: Vancouver was third-time lucky for young couple,” Vancouver Sun, 29 September 2012, E6.

- Madokoro and Molloy, “Remembering Uganda.”

- Valerie Knowles, Forging Our Legacy: Canadian Citizenship and Immigration (Ottawa: Public Works and Government Services, 2000), 90; Valerie Knowles, Strangers at Our Gates: Canadian Immigration and Immigration Policy, 1540-2006 (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2007), 213.

- Madokoro and Molloy, “Remembering Uganda.”

- Carman, “Shamshad and Jalal Jaffer.”

- Madokoro and Molloy, “Remembering Uganda.”

- Madokoro and Molloy, “Remembering Uganda;” Canada, Department of the Secretary of State, Multiculturalism Directorate, The Canadian Family Tree: Canada’s Peoples (Don Mills: Corpus, 1979), 222; Ninette Kelley, and Michael Trebilcock, The Making of the Mosaic: A History of Canadian Immigration Policy (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010), 367.

- Marcus Guido, “Historic documents of 1972 immigration of Ugandans to Canada given to Carleton,” Carleton Now (August 2012), http://carletonnow.carleton.ca/august-2012/historic-documents.

- Carman, “Shamshad and Jalal Jaffer.”

- Canada, Department of the Secretary of State, Multiculturalism Directorate, Canadian Family Tree, 222. Over 1,200 individuals were sent to British Columbia, mostly to Vancouver. Ontario received 1,847 individuals of which more than forty percent resettled in Toronto. Other settlements included Quebec (625), Alberta (211), Manitoba (200), Nova Scotia (139), Saskatchewan (73), New Brunswick (67), Prince Edward Island (15), Newfoundland and Labrador (10).

- Natasha Fatah, “Escaping a dictator’s whim,” CBC News, 27 May 2010, http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/escaping-a-dictator.

- Gerald E. Dirks, Canada’s Refugee Policy: Indifference or Opportunism? (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1977), 243.