by Jan Raska, PhD, Historian

(Updated October 19, 2020)

Introduction

After the Second World War, Canada’s response to international refugee crises varied, driven by Cold War ideology, economic self-interest, humanitarian considerations, political necessity, and public opinion. During this period, Canada became one of the world’s foremost refugee-receiving states. Successive federal governments attempted to meet Canada’s international obligations to find a permanent settlement to the plight of refugees around the world. With thousands of war-torn displaced persons and political refugees fleeing Soviet satellite states scattered across European camps, in 1951, the international community ratified the United Nations Convention relating to the Status of Refugees. The convention defined a refugee as an individual who

As a result of events occurring before 1 January 1951 and owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.[1]

At the time, Canada opted not to become a signatory to the UN refugee convention. This was because of a fear on the part of federal ‘gatekeepers,’ including the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, that refugees deemed ‘undesirable’ and ‘inadmissible’ would be irremovable from the country because they were protected from deportation under the UN convention. The UN refugee convention guaranteed asylum as an international human right and protected convention refugees from deportation to their country of origin (non-refoulement).[2]

Following the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, close to 200,000 individuals left their homeland for the West. The events of 1956 were some of the earliest images of an uprising broadcast on television to the world. Soon after, the Canadian public began to call on federal officials to help these “freedom fighters.” Since many of the refugees were anti-communists, young, educated, and experienced professionals with multilingual abilities who could make a significant contribution to the Canadian economy, federal immigration officials viewed them as the ‘cream of the crop.’ Canada waived existing admissions criteria, including medical and security screening, to resettle approximately 37,500 Hungarian refugees between 1956 and 1958.

Nearly a decade later, in 1967, federal officials liberalized Canadian immigration policy with the introduction of Order-in-Council P.C. 1967-1616. Commonly referred to as the points system, this regulation removed all ethnoracial and geographic restrictions. A year later, Canada once again waived its admissions criteria including medical examinations and security assessments to resettle close to 12,000 Prague Spring refugees who fled the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia. Similar to the Hungarian refugees, many of the individuals who fled their homeland in 1968 were young and well-educated professionals who were also anti-communist. Canadian immigration officials viewed these refugees as ‘good material’ due to their linguistic abilities and work experience. Although Canada became a signatory to the UN refugee convention in 1969, the country remained without an official refugee policy until the implementation of the 1976 Immigration Act, which defined Canada’s legal obligations toward refugees. Under the Immigration Act, three separate classes for admission were recognized: independent immigrant selected through the points system, family reunification, and refugees.

What about some of the refugee movements that were admitted to Canada since the events of Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968? Below, three summaries of comparative cases highlight these governmental and public concerns: the 1973 Chilean refugees; the Indochinese refugees who fled civil war in Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos between 1975 and 1981; and the Somali refugees who sought refuge elsewhere from drought, famine, and civil war between 1989 and 1995.

Chilean Refugee Movement, 1973

In September 1973, a military coup led by General Augusto Pinochet displaced left-wing elements in the Chilean government and led to the death of the country’s democratically elected socialist-communist President, Salvador Allende. Initially, Canada moved slowly to admit refugees due to their leftist political leanings, and more than a year after Allende’s assassination, Canada reluctantly accepted Chilean refugees. Immigration officials were cautious to admit left-leaning refugees fleeing right-wing states, as opposed to admitting large groups of refugees fleeing communist regimes during the Cold War. Indeed, the Canadian government demonstrated greater caution and remained reluctant to implement a liberal refugee policy than with previous refugee resettlement programs.[3] It is telling, for example, that the early press releases and public statements made by federal officials regarding the Chilean crisis came from the Department of External Affairs rather than Manpower and Immigration. In short ideological considerations replaced racial criteria as a discriminatory factor in refugee admissibility.[4] Due in part to pressure from university committees, church and humanitarian groups, the federal government eventually permitted nearly 7,000 Chilean refugees to permanently resettle in Canada.

Indochinese Refugee Movement, 1975-1981

When compared with the admission of Chilean refugees, the Canadian government was far more charitable in its response to the predicament of the Indochinese ‘boat people’ – individuals who fled communist regimes in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. Following the fall of Saigon in 1975, thousands of individuals and families fled their homelands in search of safe refuge across south Asia. It took three years before Canada responded to this movement of refugees. The catalyst for the federal government’s response was the plight of the freighter Hai Hong. With a broken engine, the vessel held approximately 2,500 refugees. Denied permission to dock in Malaysia, the ship anchored off the coast of Port Klang. The Hai Hong was short of water, food, and medical supplies. It was overcrowded and facing a dire situation. In 1978, the Canadian government announced that it would resettle 600 refugees on board the vessel. The election of Prime Minister Joe Clark coincided with an increase in the number of refugees fleeing Vietnam. Largely due to intense political lobbying by church and humanitarian groups, in July 1979, the federal government agreed to admit 50,000 refugees by the end of 1980. During the Indochinese refugee program, over 60,000 individuals were permanently resettled in Canada between 1979 and 1981. In all, over 77,000 Indochinese refugees were permanently resettled in Canada between the fall of Saigon and the conclusion of the special program for Indochinese refugees.[5] The Hai Hong incident initiated a large-scale private sponsorship movement in Canada that also led to the widespread implementation of Canada’s new refugee policy.[6]

Somali Refugee Movement, 1989-1995

Unlike the previous two case studies, the arrival of Somali refugees was not the result of a government-sponsored refugee program that responded to a specific international event or crisis. Following widespread droughts in the 1970s, Somalia was ravaged by famine and later civil war. Popular opposition to the Marxist government of President Siad Barre was soon organized by diverse political groups who were divided by clan membership. In 1986, a civil war erupted in Somalia which forced the UN and various international aid agencies to withdraw from the country. Facing droughts, famine, starvation, and civil war, thousands of Somalis fled their homeland in search of refuge. In 1989, the acceptance rate for Somali refugee claimants in Canada was 95 percent. This led to an expedited process a year later. In 1991 and 1993, Somalia was the largest source of refugee claimants in Canada, and the third-largest in 1992. In December 1992, the UN Security Council authorized an international peacekeeping mission. Humanitarian relief soon followed saving an estimated 300,000 Somalis from starvation. As clan factionalism increased, Somalis continued to resettle elsewhere including the United States and Canada. In 1995, the international peacekeeping mission ended. The Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada later indicated that by the mid-1990s, the migration of Somali refugees to Canada had reached the stage of family reunification.[7]

Conclusion

Due largely to lobbying efforts by international organizations, domestic humanitarian groups and churches, pressure from the press, and political will on the part of the federal government, immigration officials ultimately admitted these aforementioned refugees into Canada.

Initially, some Canadians feared the admission and resettlement of these refugee movements. Over time, the Chilean, Indochinese, and Somali refugees adapted well to their new country, becoming fully integrated into Canadian society.

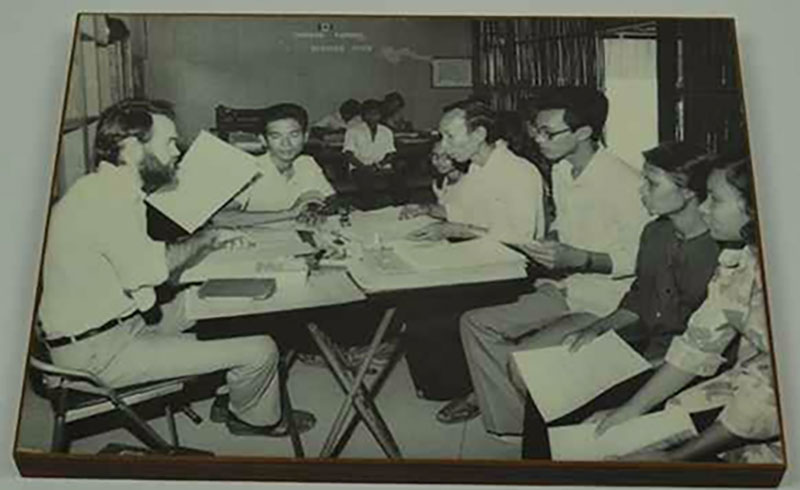

Credit: “Faces behind the Lines” by Liza Linklater & James Trottier, August 1983, Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2014.377.12)

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees,” http://www.unhcr.org/3b66c2aa10.html, 14.

- Library and Archives Canada, PCO fonds, RG 2, Series A-5-a, vol. 2648, file “Cabinet Conclusions,” item 11117, title “United Nations; Convention on Refugees and Protocol on Stateless Persons,” 4 July 1951, reel T-2367.

- Gerald Dirks, Canada’s Refugee Policy: Indifference or Opportunism (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1977), 247; Reginald Whitaker, Double Standard: The Secret History of Canadian Immigration (Toronto: Lester & Orpen Dennys, 1987), 255-261; Freda Hawkins, Canada and Immigration: Public Policy and Public Concern (Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1988), 385.

- See for example, Dirks, Canada’s Refugee Policy, 244-250; Whitaker, Double Standard, 254-261; Valerie Knowles, Strangers at Our Gates: Canadian Immigration and Immigration Policy, 1540-2006 (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2007), 215; Francis Peddie, Young, Well-Educated and Adaptable: Chilean Exiles in Ontario and Quebec, 1973-2010 (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2014.

- Valerie Knowles, Forging Our Legacy: Canadian Citizenship and Immigration, 1900-1977 (Ottawa: Public Works and Government Services, 2000), 91-93; Knowles, Strangers at Our Gates, 216-217.

- Dara Marcus, “The Hai Hong Incident: One Boat’s Effect on Canada’s Policy towards Indochinese Refugees,” Canadian Immigration Historical Society / Société Historique de l’immigration Canadienne (CIHS-SHIC), accessed 22 November 2021, http://cihs-shic.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Marcus_IMRC_Submission.pdf, 2, 16.

- John Sorenson, “Somalis,” In Encyclopedia of Canada’s Peoples, ed. Paul Robert Magocsi, 1195-1201 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999), 1196-1197.