by Western University's MA Public History Program Students

The migration of the New England Planters was the first significant migration to the Atlantic colonies in British North America. In the wake of the deportation of the Acadians in 1755, newly cultivated lands opened up in Nova Scotia, which needed to be populated. Roughly eight thousand men and women from New England came to settle in the Annapolis Valley of Nova Scotia, and in the Upper St. John River Valley of present-day New Brunswick, between 1759 and 1768. They left a legacy that can be found in the social, religious, and political life of Atlantic Canada.

Did You Know?

8,000 New Englanders came to present-day Nova Scotia and New Brunswick from 1759 to 1768.

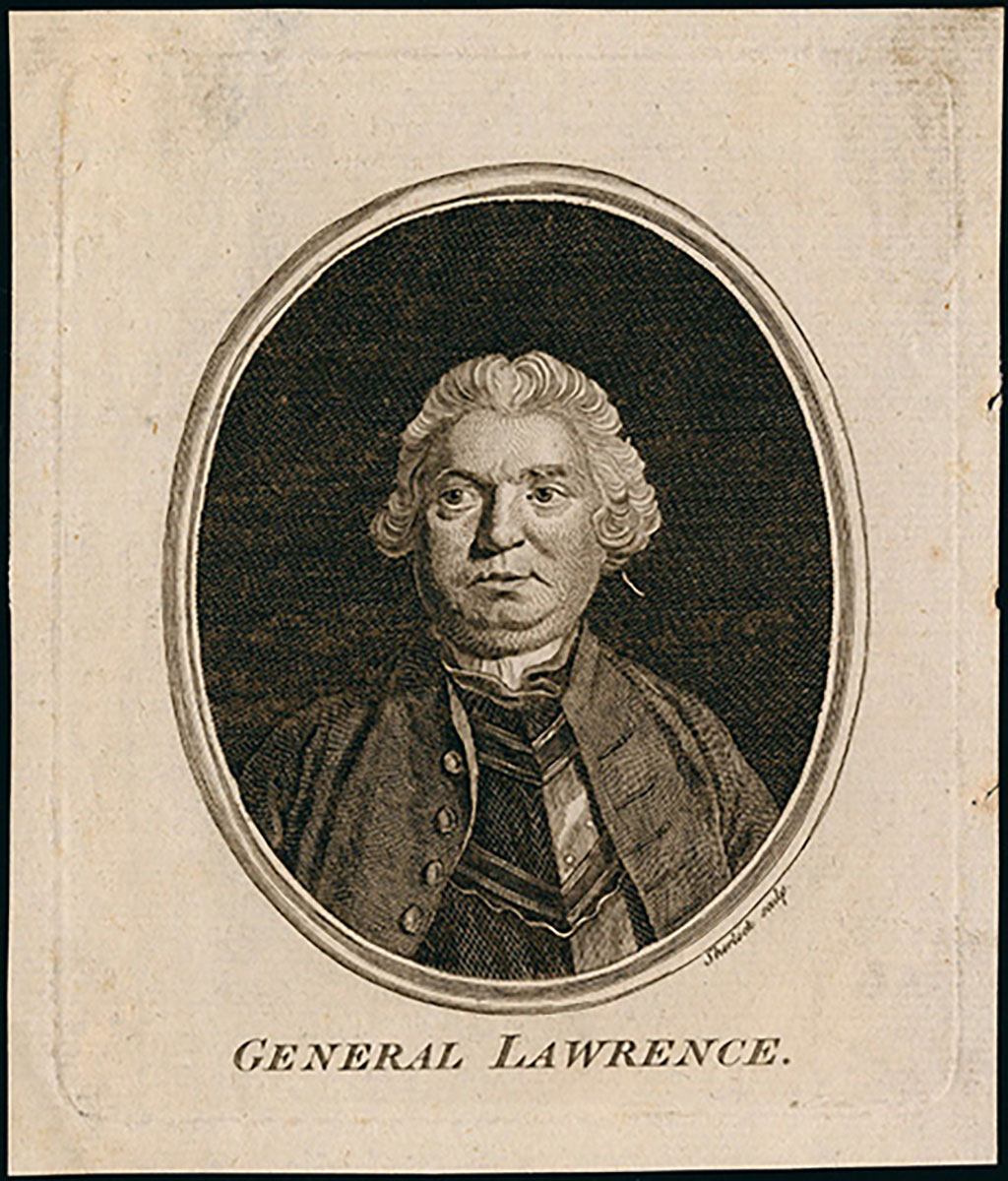

The first move towards settling the newly vacated lands after the Acadian Deportation was made via the Proclamation by General Charles Lawrence to the Boston Gazette on 12 October 1758, inviting settlers in New England to immigrate to Nova Scotia. The agriculturally fertile land in Nova Scotia would be a driving force in enticing the emigrants, but the New England colonists were wary.[1] Lawrence sent a second Proclamation on 11 January, 1759 stating that in addition to land, Protestants would be given religious freedom, and a system of government similar to that in New England would be in place in the Nova Scotia settlements.[2]

Land was the most influential reason for this emigration from New England, and the primary incentive for the move to Nova Scotia. Under the terms of Lawrence’s Proclamations, every head of family was entitled to one hundred acres of wild land and another fifty acres for each member of his household, up to one thousand acres.[3] The land would be free of charge for ten years, after which a small rent would be charged. Grantees would have to improve one-third of their land every ten years, until all was cultivated. Lawrence’s offer made available a vast amount of quality farmland at a time when there was virtually no free land left in New England, due to a massive population increase to the area.[4]

Credit: Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1965-52

In the mid-eighteenth century, most New Englanders were desperately poor. For many generations, fathers had split up their lands to give to their sons, which meant they had very little land to farm themselves. The promise of over a hundred acres of land in Nova Scotia was enticing. Others were excited about the prospect of being close to the Grand Banks, which had a seemingly unlimited supply of fish. Unfortunately the promises and expectations of the settlers were initially not fully realized. The devastation of Acadian farms arising from the war between the British and the French made much of the offered land initially unusable.[5] Regardless of these issues, the “Planters” emigrated and adjusted to the new circumstances that presented themselves in Nova Scotia, implementing a societal structure similar to that in New England. Although they were physically separated from family members left behind in New England, many maintained close ties through letters and occasional visits.[6]

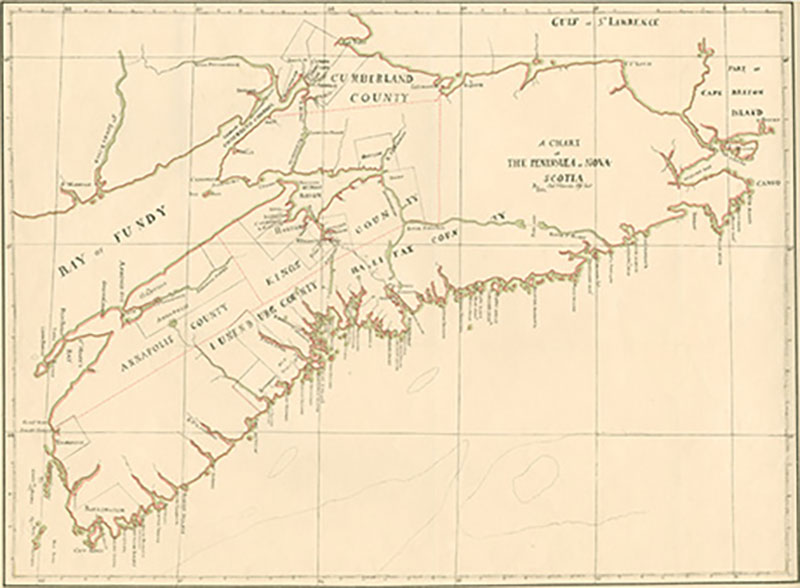

Credit: Nova Scotia Archives Map Collection: 3.5.3 1761 Nova Scotia (scan 201001026)

Did You Know?

The British government issued two different proclamations inviting New England Planters to settle in Nova Scotia.

Planters also came to Nova Scotia with extended family networks; it was rare for single men of marriageable age to come by themselves. Families were often large and multi-generational, ranging in age from newborns to individuals in their mid-eighties.[7] The migration to Nova Scotia saw the continuation of the multi-generational family unit, which was a key structure of New England society. Sarah Foster, a New England Planter, came to settle Granville Township in the Annapolis Valley with her multi-generational family unit. She immigrated with her six children, four of whom were already married with young families of their own. Sarah’s two remaining children married shortly after their arrival.[8] Looking closely at the family histories of the Planters, it is apparent that family was of high importance in Planter settlements. For example, the distribution of lands was often re-organized by Planters upon arrival in Nova Scotia, in order to support a more convenient familial relationship. Families would arrive to discover that their allotted properties were scattered and separated from other family members, so they would often trade and sell in order to settle closer to one another. This allowed easier access to family members and the continuation of the family relationship. Two of Sarah Foster’s sons lived on adjoining lots, for example, while their sister Judith Chute, lived a mile away. Sarah Foster’s son Jeremiah, however, returned to New England, settling in Winthrop, Maine.[9] This reflected another Planter dynamic, in which the return of family members to New England strengthened the relationship between the colonies of New England and Nova Scotia.

Credit: Nova Scotia Archives (scan 201002424)

The first generation of Planters in Granville, Nova Scotia, grew up in a very different environment than their parents. Regardless of the ties of family and the relationship to their home country, Nova Scotia was not New England. During the mid-eighteenth century, Nova Scotia was a multicultural place, thus this first generation became neighbours to settlers who came from different ethnic origins, spoke different languages and practiced different religions. And not all settlers who came as Planters had been native to New England either – some had origins in Germany, Scotland, Ireland and England.

However, the choice of marriage partners demonstrates the apprehension that some New England settlers felt about this new diverse society. Some families were so hesitant to integrate that they chose to marry within their own family rather than marry into other families in the community. This practice is evident in the Foster-Chute family, some of whose members continued the practice of intermarriage well into the mid-nineteenth century.[10] But many of the Planters in Granville did not share similar reservations about the diversity of the community. Despite maintaining close ties with those back in New England, there is little indication of parents contacting old networks of family and friends to find suitable brides and grooms for their children. For the most part, those who lived in Planter settlements in Nova Scotia would marry those with whom they grew up.[11]

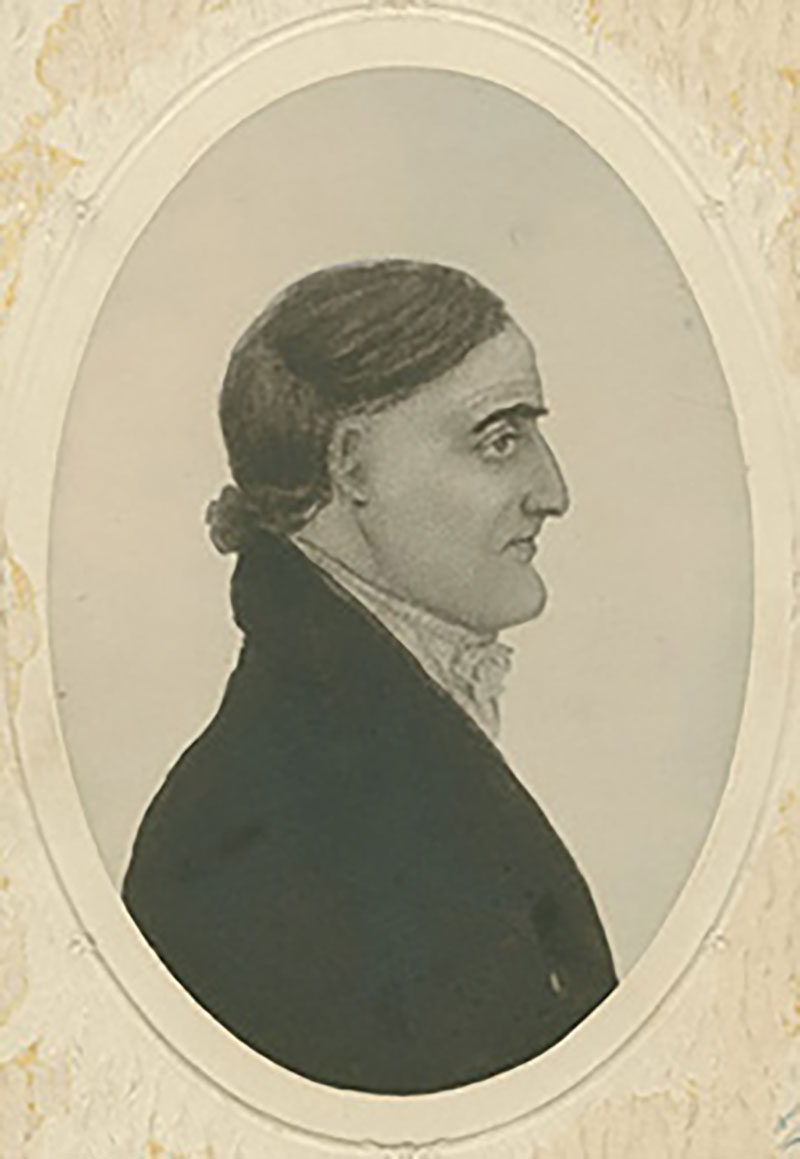

Credit: Nova Scotia Archives, Documentary Art Collection, 1979-147 no. 230 (scan 201002434)

Did You Know?

Planters were critical to the founding of Acadia University in 1838.

The first local institutions created by the New England settlers were largely associated with maintaining social order and the protection of property. For this first generation of Planters in Nova Scotia, survival was dependent on becoming economically self-sufficient. Schools, for example, were scarcely visible in the first generation of settlements because children were needed at home to help with the farm. Churches were rare as well. One of the first institutions that affected the townships was the court system. Jonathan Belcher, Supreme Justice of the Nova Scotia Supreme Court and acting Governor, called for strict laws against profanity and Sabbath-breaking.[12] Although the early years of Planter settlement lacked an organized congregation or ministers, they were determined to maintain proper behaviour, which was a fundamental belief of their Puritan ancestors. The courts not only controlled social aspects of the community, but infrastructure as well. Some of the first court documents in the settlements, for example, reflected the importance of road-building to the communities. Farming communities depended on roads for accessibility to larger centres, which gave them access to broader markets that were accessed through ocean ports in Halifax.[13]

Credit: Nova Scotia Archives Photograph Collection: People: Perkins, Simeon (scan 200716218)

Did You Know?

Prime Ministers Sir Charles Tupper and Sir Robert Borden were direct descendants of New England Planters.

By the mid-1760s, the immigration of the Planters began to dwindle. Some had returned to New England and some sought new land west of the Appalachian barrier, or in newly developed areas in present day Vermont and New Hampshire.[14] But many stayed and some of the descendants of the original Planters became people of influence in Nova Scotia and elsewhere in Canada. Sir Charles Tupper and Sir Robert Borden, both Canadian Prime Ministers, were direct descendants of the New England Planters. Planters also played an important role in the founding of Acadia University in Wolfville, Nova Scotia, in 1838.[15]

The Planter settlements had a strong impact on Nova Scotia and what is now New Brunswick. The Planter immigration scheme specifically targeted a group of people that the colonial authorities deemed as desirable to populate land formerly owned by Acadians. Although the first Planters were met with hardship, the communities they built helped to create the unique makeup of two Atlantic provinces.

Timeline:

1755 - The Acadian Deportation begins.

12 October 1758 - The first proclamation is sent out by Lieutenant General Lawrence calling for New England immigrants to send settlement inquiries for the available Acadian lands of Nova Scotia.

11 January 1759 - The second proclamation is issued by Lieutenant General Lawrence addressing the initial concerns Planters had about immigrating to Nova Scotia.

November 1759 - A terrible storm hits Nova Scotia affecting the flow of immigrants into Annapolis, Minas, and Chignecto. Here the advanced dyke systems are destroyed, allowing great areas of land to be flooded with salt waters and consequently unable to bear grain crops for the next three years. A decision is made to check the effects of the damage before the migration of the New Englanders, pushing their migration to 1760.

1760-1768 - The largest influx of Planter immigration brings roughly 8,000 New England Planters to Nova Scotia and present-day New Brunswick. By the mid-1760s migration slows and many Planters either return to New England, or seek new lands and opportunities in the West.

May 1760 - Charles Morris, Chief Surveyor, travels to the township of Annapolis, Nova Scotia and is greeted by the first wave of settlers who sailed on the ship Charming Molly.

1775-1783 - The American Revolution breaks out between Great Britain and its Thirteen Colonies in North America.

1783 - Those who remained loyal to the British Crown begin to seek refuge in Canada when the Revolution ends. Roughly 35,600 Loyalists migrated to Nova Scotia.

- R.S. Longley, “The Coming of the New England Planters to the Annapolis Valley,” In They Planted Well: New England Planters in Maritime Canada, edited by Margaret Conrad (Fredericton: Acadiensis Press, 1988) 17-18.↩

- Longley, “Coming,” 18; Charles Lawrence, Proclamations, Nova Scotia Archives, MG100 Vol. 47 #50.↩

- Longley, “Coming,” 18.↩

- Longley, “Coming,” 18.↩

- Barry Moody, “Growing Up in Granville Township, 1760-1800,” In Intimate Relations: Family and Community in Planter Nova Scotia, 1759-1800, edited by Margaret Conrad (Planter Studies 3. Fredericton: Acadiensis Press, 1995) 82-83, 85.↩

- Moody, “Growing Up in Granville,” 81.↩

- Moody, “Growing Up in Granville,” 79.↩

- William Edward Chute, A Geneaology and History of the Chute Family in America, (Salem, Mass., 1894) 322.↩

- Chute, Geneology, 322.↩

- Moody, “Growing Up in Granville,” 84.↩

- Moody, “Growing Up in Granville,” 84.↩

- Patricia A. Norred,“Reinventing Community: Connecticut Planters in Nova Scotia, 1759-1779,” (University of Missouri-Colombia: ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1996) 159.↩

- Norred, “Reinventing,” 161.↩

- George Rawlyk, Nova Scotia’s Massachusetts: A Study of Massachusetts-Nova Scotia Relations, 1630-1784 (Montreal and London: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1973) 222.↩↩

- James E. Candow, “The New England Planters in Nova Scotia,” ed. John Thomas, Planter Notes 6, no. 2 (April 1995), 1-6.↩