by Western University's MA Public History Program Students

Fugitive or Free?

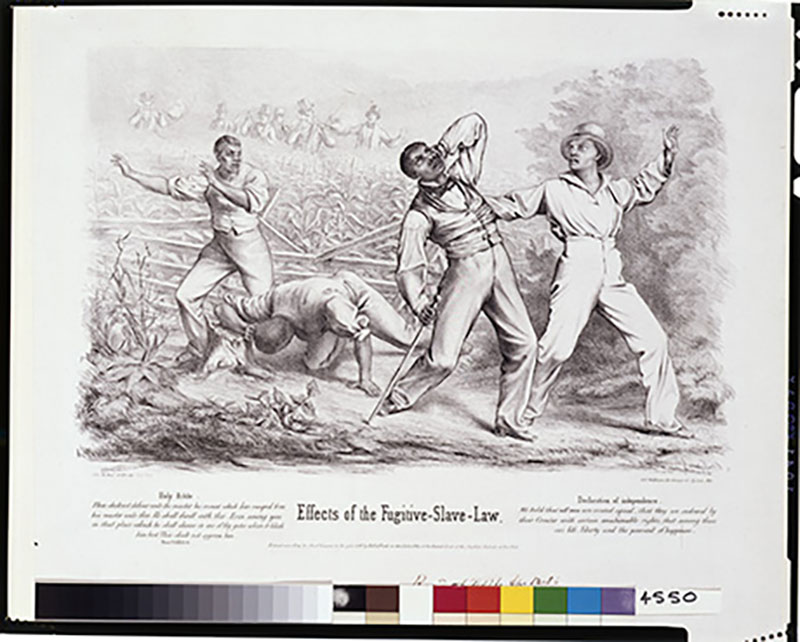

Prior to 1850, fugitive slaves who escaped from the southern United States to the northern states were considered to be free. However, after the passing of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, the northern states were no longer a safe haven. Escaped slaves could be captured by slavecatchers and returned to their owners.[1] This also meant that people who had escaped slavery by entering a free state years earlier could be returned to slavery. Because of racism in American society at the time, it was much easier for a white slave owner to claim that someone was their escaped slave than for a black person to prove they were not. The same threat existed for all free blacks. The Act Against Slavery, passed in 1793, made Upper Canada (part of what is now Ontario) the first British colony to prohibit slavery. Once crossing into Upper Canada, all men, women, and children, were free.[2]

Credit: Library of Congress, LC-USZC4-4550

The Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a system of safe houses run by abolitionists in both free and slave states, as well as in Canada. Those who helped fugitive slaves on their journey to freedom -- free blacks, Quakers, and other activists -- risked their lives fighting against slavery. Though there was never a real railroad, safehouses were called stations, those who lived in them were called stationmasters, and those who led fugitive slaves towards freedom were called conductors.

New Land, New Life

In Canada West (formerly Upper Canada), black men had the right to own property and vote if they met property requirements.[3] All black persons could earn a living, get married, and start a family. With assistance from Canada’s government and abolitionist societies in Canada and the United States, building a new life in Canada was possible. Land was sold to refugees at a reduced rate and education subsidies were available.[4]

Did You Know?

After 1841 Upper Canada was re-named Canada West, which makes up part of the present-day Canadian province of Ontario.

Reception

When fugitive slaves first came to Canada West, most of them settled near the American border. This allowed them to stay closer to family members who were dispersed across the United States. At this time white citizens behaved in a mostly neutral way towards them.[5] After 1840, white citizens started to become fearful when fugitive slaves began to arrive in larger numbers. Some were scared that these fugitive slaves would be unable to work and would live off government assistance.[6] During the American Civil War, residents of Canada West started a petition to close the Canadian border to all new black immigrants. They feared an unmanageable influx of newly freed blacks once slavery was abolished.[7]

Creating Community

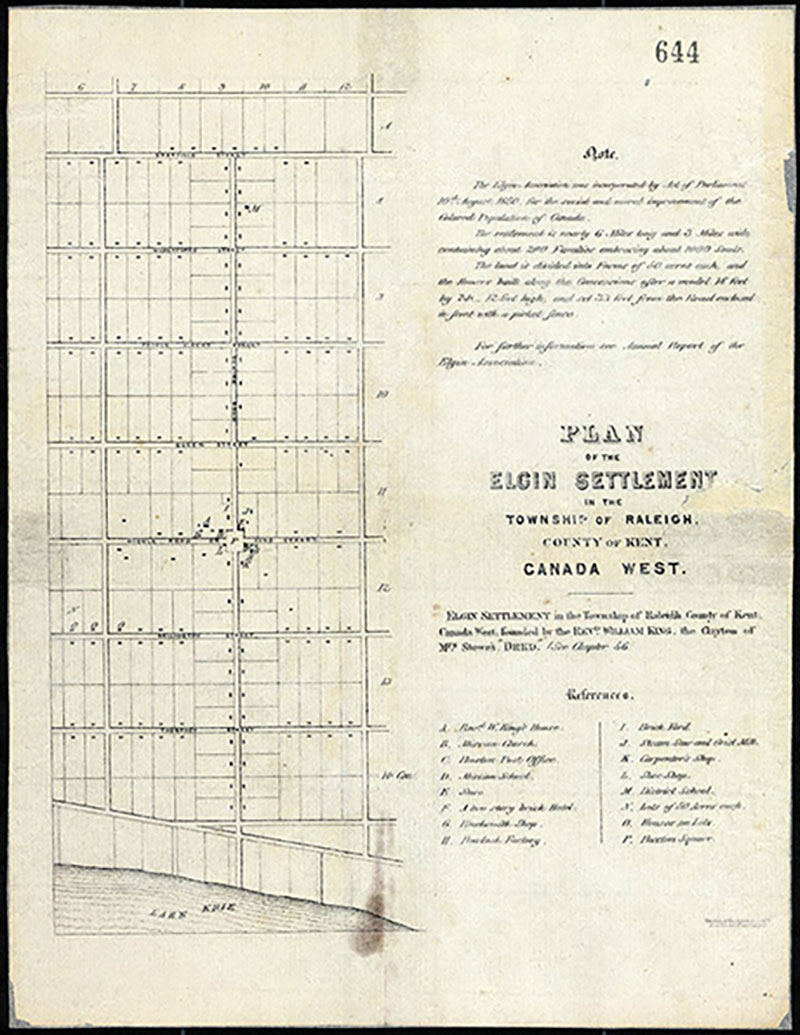

Black immigrants spread out around various towns and settlements, including Hamilton, St. Catharine’s, Windsor, and Toronto. The largest concentration of black immigrants and refugees was in the Chatham-Kent region of Canada West.[8] As early as the 1820s a number of all-black settlements were established. The first settlement of this kind was Wilberforce, founded by former slave, James C. Brown.[9] In 1834, escaped slave Josiah Henson founded the Dawn Settlement .[10] Both of these settlements were a beacon to those travelling along the Underground Railroad. Eventually Wilberforce and the Dawn Settlement were abandoned or annexed into other towns. The most successful settlement was the Elgin Settlement, including the Buxton Mission developed by abolitionist Reverend William King. The Buxton Mission still exists today as North Buxton, Ontario.[11] There were disagreements within black communities in Canada about whether self-segregation was a good idea. Some believed it was the best way to protect themselves while others worried that it was maintaining inequality.[12] Despite these disagreements, these all-black settlements provided escaped slaves with the opportunity to gain a formal education or learn skilled trades within their own communities.[13]

Plan of the Elgin Settlement, ca. 1860.

Credit: Library and Archives Canada/William King collection/e000755345

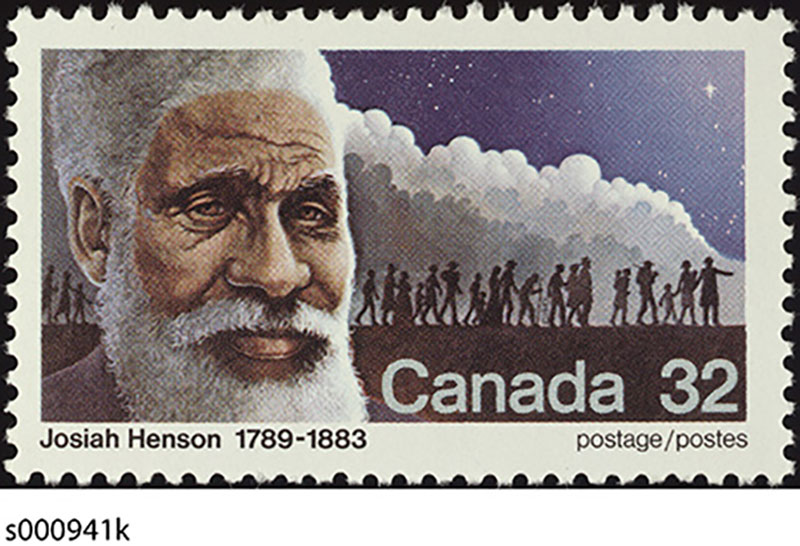

Josiah Henson

Josiah Henson was born a slave in Maryland in 1789, and eventually escaped with his family to Canada in 1830.[14] He founded the all-Black settlement of Dawn Township, which became the Dawn Settlement. Henson established himself as a Methodist preacher in the region and believed in the importance of employment and education for black refugees.[15] He was the inspiration for the anti-slavery novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, by Harriet Beecher Stowe, published in 1852. Henson was also a prominent abolitionist speaker, and lived in Canada until his death in 1883.[16]

Credit: Library and Archives Canada/Canada Post Corporation

Making Their Mark

Regardless of where they settled in Canada, black immigrants who came to Canada on the Underground Railroad made lasting contributions to their communities. Many became farmers, growing crops like wheat, peas, tobacco, and hemp. Others were skilled tradesmen, working as blacksmiths, shoe makers, and wagon makers.[17] Like their white counterparts, most black women did not work outside the home. They raised their children, or worked for wages as seamstresses and washerwomen. Most importantly they proved that they were capable of forming and participating in communities when given the opportunity to do so.

EXTRA EXTRA!

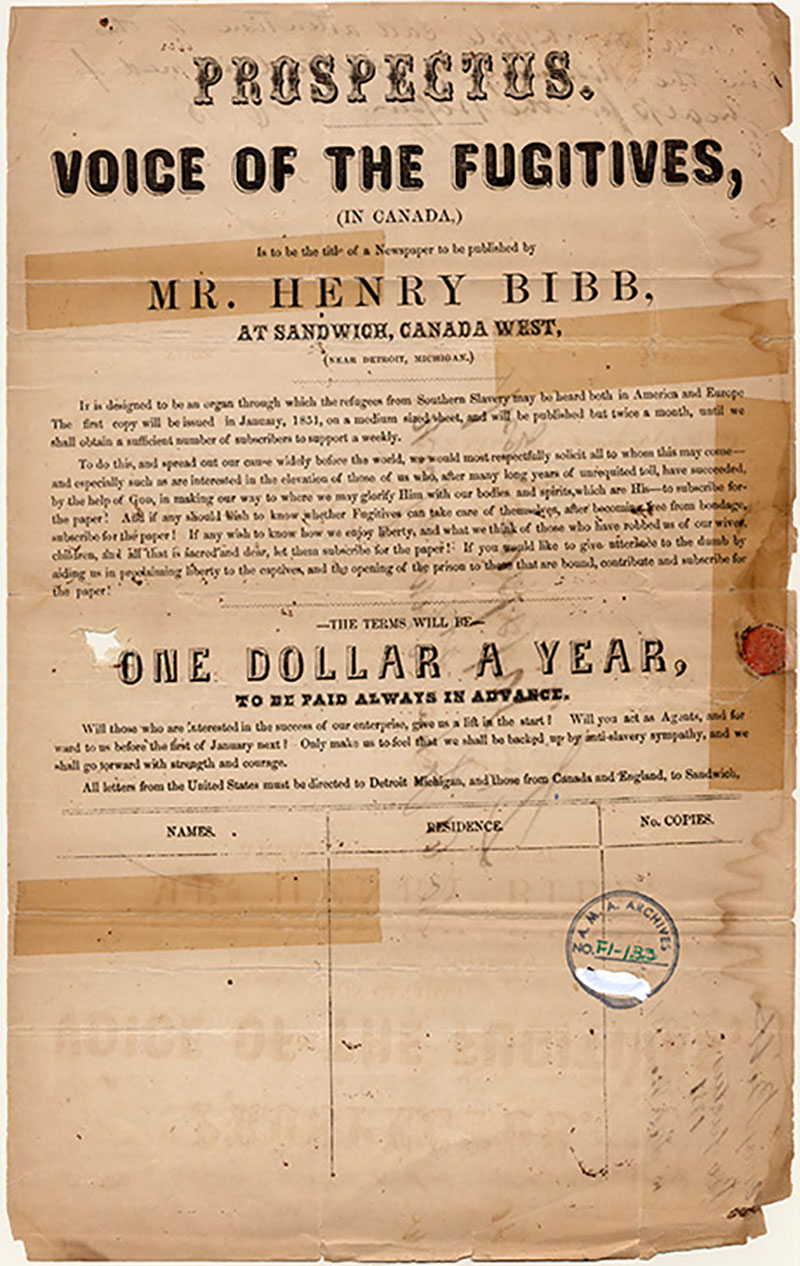

Credit: Library and Archives Canada/C-029977

Several newspapers were founded in order to increase awareness of the opportunities for blacks in Canada, to share news, and to promote the abolition of slavery. The Voice of the Fugitive was first published in Sandwich, Canada West, in 1851, and was one of the earliest black newspapers in Canada.[18] Henry Bibb, a fugitive slave from Kentucky, was the editor. A few years later, Mary Ann Shadd Cary created a second newspaper, called the Provincial Freeman.[19] Shadd Cary was from Delaware, and was the daughter of a free black man, Abraham Shadd, the first black man to be elected to political office in Canada in 1859.[20] Bibb and Shadd Cary’s early friendship eventually developed into a bitter rivalry, as their views differed on the integration of blacks into white society.[21]

Voice of the Fugitive, 1851

Credit: Amistad Research Center/American Missionary Association Archives ama0015

Did You Know?

With some qualifications, upon arriving in Canada, black men were given the right to vote. Women in Canada could not vote in federal elections until 1919, and Aboriginal Peoples were not given the right to vote until 1960.

Conclusion

On the surface, life appeared to be much better in Canada; however, this newfound freedom had limits. Although slaves were granted freedom in Canada, they still faced racism, oppression and segregation. Over time these sentiments pushed blacks away from Canada, while other factors pulled them back towards the United States. Conditions for blacks improved immensely in the United States with the passing of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, which abolished slavery.

After the Emancipation Proclamation was signed, about two thirds of the black refugees in Canada returned to the United States. Those who stayed in Canada continued to contribute to their communities and in time tore down many racial barriers. Many of the descendants of those who returned to the United States can trace their heritage back to Canada, following the footsteps of their ancestors who travelled via the Underground Railroad.

Timeline:

1793 - The Act Against Slavery is passed by John Graves Simcoe in Upper Canada.

1834 - British Emancipation Act officially eradicates the institution of slavery throughout the British Empire.

1842 - The Dawn Settlement is founded near Dresden, Canada West.

1849 - The Elgin Settlement, Canada West is founded.

1850 - The Fugitive Slave Act is passed in the United States.

1851 - The Voice of the Fugitive newspaper is first published in Sandwich, Canada West.

1853 - The Provincial Freeman newspaper is first published in Windsor, Canada West.

1854 - Henry W. Bibb passes away at the age of 39.

1861 - American Civil War begins.

1863 - President Lincoln issues the Emancipation Proclamation, thus freeing all slaves in the United States.

1865 - American Civil War ends.

1883 - Josiah Henson passes away in Dresden, Ontario.

1893 - Mary Ann Shadd Cary passes away in Washington, D.C.

- Robin Winks, The Blacks in Canada: A History (Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 1971 Blacks in Canada: A History, 217.↩

- William R. Riddell, "The Slave in Upper Canada," The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 14, no. 2 (1923): 256-258.↩

- Fred Landon, "Henry Bibb, a Colonizer," The Journal of Negro History, 5, no. 4 (1920): 447.↩

- Ibid., 442-443.↩

- Jason H. Silverman, Unwelcome Guests: Canada West's Response to American Fugitive Slaves, 1800-1865 (Millwood, N.Y.: Associated Faculty Press, 1985), 22.↩

- Silverman, Unwelcome Guests, 34.↩

- Ken Alexander and Avis Glaze, Towards Freedom: The African-Canadian Experience (Toronto: Umbrella Press), 1996, 79.↩

- Boulou Ebanda de B’beri et al. The Promised Land: History and Historiography of the Black Experience in Chatham-Kent’s Settlements and Beyond. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014), 22.↩

- Kerry Walters. The Underground Railroad.: A Reference Guide. (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2012) 109.↩

- Jacqueline Tobin, From Midnight to Dawn: The Last Tracks of the Underground Railroad. (Toronto: Doubleday 2007), 16.↩

- Buxton Museum, Buxton, 21975 A. D. Shadd Rd, North Buxton, Ontario, N0P 1Y0, Visited Nov. 6, 2015↩

- Alexander and Glaze, Towards Freedom, 66.↩

- Alexander and Glaze, Towards Freedom, 65↩

- Josiah Henson, Father Henson’s Story of His Own Life. (Cleveland: H.P.B. Jewett, 1858), 2-3.↩

- Ibid., 24.↩

- Peggy Bristow, “Whatever you raise in the ground you can sell in Chatham: Black Women in Buxton and Chatham, 1850-1865” in We’re Rooted Here and they Can’t Pull us Up, Essays in African Canadian Women’s History (Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 1994), 87-90↩

- The Voice of the Fugitive. INK-ODW Newspaper Collection. Accessed October 1, 2015. http://ink.ourdigitalworld.org/vf.↩

- The Provincial Freeman. INK-ODW Newspaper Collection. Accessed October 1, 2015. http://ink.ourdigitalworld.org/pf.↩

- The Provincial Freeman. INK-ODW Newspaper Collection. Accessed October 1, 2015. http://ink.ourdigitalworld.org/pf.↩

- The Provincial Freeman. INK-ODW Newspaper Collection. Accessed October 1, 2015. http://ink.ourdigitalworld.org/pf. Gael Greene, "Shadd, Abraham Doras," Accessed, March 14, 2016, http://www.blackpast.org/gah/shadd-abraham-doras-1801-1882↩

- The Provincial Freeman." INK-ODW Newspaper Collection. Accessed October 1, 2015. http://ink.ourdigitalworld.org/pf↩

Did You Know?

- The Right to Vote: “Women's Suffrage" The Canadian Encyclopaedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/collection/womens-suffrage-in-canada Accessed March 22, 2016;

- Natasha L. Henry, "Black Voting Rights," The Canadian Encyclopedia, Published Jan 18, 2016, Accessed, March 14, 2016, http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/black-voting-rights/;

- Jackal, Susan. "Women's Suffrage" The Canadian Encyclopaedia. Published August 6, 2013. Accessed, March 14, 2016.http://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/womens-suffrage/;