By Haroon Khalid, Anam Zakaria, and Emily Burton, PhD, Oral Historian

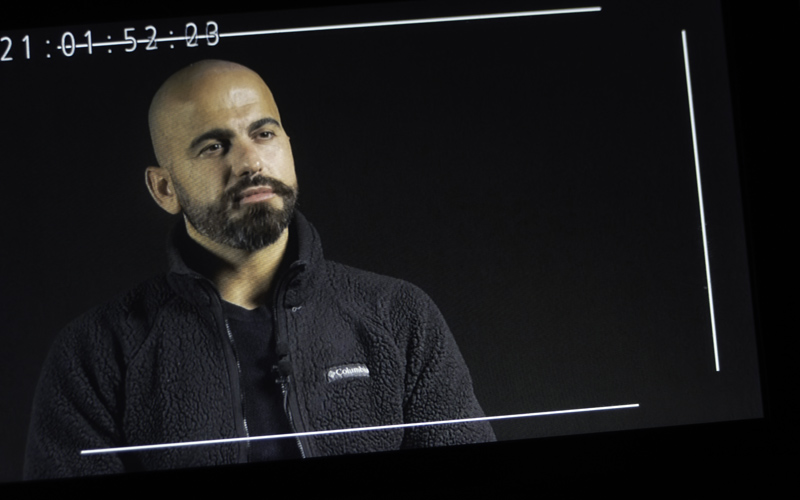

“Reality is reality. It is more difficult than imagination…We’re adapting, whatever’s happening. We were okay, we’re still okay, and we will always be okay, hopefully.” Rammah Mohammad.[1]

Introduction

In 2024, the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 (CMIP) collaborated with Qissa, a Toronto-based non-profit organization that documents, archives, and exhibits oral histories of immigrants to Canada, for the project Driving Canada: A Front Seat View of Immigration through Uber. The project documented diverse immigrant experiences, using Uber as a unique entry point into people’s journeys. We met in the Greater Toronto Area to collect oral histories of recent immigrants to Canada who are currently driving, or have driven Uber in the past.

In this article, Haroon Khalid and Anam Zakaria of Qissa, and Emily Burton of the CMIP, provide an overview of the collaboration, while also sharing some of our thoughts and reflections.

Project Background And Beginnings

Haroon Khalid:

While speaking about his experiences as an Uber driver, Yalgar Singh, one of the project participants, talked about seeing the early rumblings of an economic recession, experienced by a drop in the number of passengers, and more Uber drivers on the road: “Nowadays, I believe they are not even issuing licenses.”[2]

In many ways, this comment by Yalgar, captures the essence of what inspired Qissa to conceptualize this project. Anam and I were having conversations with the drivers every time we would take an Uber, and many of these conversations were reflecting some of the broader socio-economic challenges of the country. We met a professor who took up driving Uber to counter the rising cost of living. We met a young immigrant who had sent his infant daughter to his parents in India, because they could not get a spot in any daycare in the Greater Toronto Area, highlighting the challenges of finding affordable childcare. We meet numerous recent immigrants, who were struggling to transition into the Canadian job market, because of an over-emphasis on ‘Canadian experience,’ a systemic issue faced by many newcomers.

Anam Zakaria:

In many ways my interest to the project is connected with my own experiences of being a recent immigrant. After moving to Canada in 2019, I ran into several systemic barriers in the job market. At first, for months I would not hear back on my job applications. I was then advised to remove Pakistan from my resume. Interview calls started coming in after but soon I ran into another challenge. I was either overqualified for positions or did not have enough ‘Canadian experience’ for more senior roles. Eventually when I did finally land my first job a year later, at a settlement agency working with other newcomers and refugees, I saw how their international experience, particularly for immigrants from the Global South, was discounted and undervalued. I recall a particular case, of a pediatrician who had 15 years of work experience in India, struggling to land a job as a receptionist. I encountered many other such instances during my time at this agency.

Not finding jobs in line with their professional career, many newcomers join the gig economy, for survival as well as the flexibility. In Toronto, I found that most Uber drivers and food delivery workers were racialized, recent immigrants. Some of them were ENTs, veterinarians, professors, and engineers in their home country. I wanted to tell their story – their story after arriving in Canada.

We often view immigration as a journey of upward mobility. For many it is. For many it is not. For many it is both. This nuance is important to understand and document, so that we can begin to explore the layered and diverse experiences of newcomers. This helps breakdown uniform ideas of immigrants and their stories, both before and after coming to Canada.

Emily Burton:

I first connected with Qissa in January, 2024. Anam reached out to me with an interest in exploring a possible collaboration. As Anam noted then, she had been working with oral histories in South Asia since 2010, and was interested in documenting oral histories of immigrants in Canada. Anthropologists and oral historians, Anam and Haroon had worked on several oral history projects prior to moving to Canada, with eight published books between them that use oral histories as primary methodologies.

I responded right away. As the CMIP’s Oral Historian, I am very interested in collaborative oral history projects that help us collect interviews and share stories in different ways, and in working with people whose migrant experiences are closer to the people being interviewed.[3] I came to Canada initially as a young child, with immigrant parents from England and Peru. We lived in four different provinces growing up, and also moved back to Peru, as my parents pursued educational and economic opportunities. This personal connection to experiences of dislocation and migration, including the struggles families face in adjusting to a new country, helps me understand other migration journeys, although many journeys are also very different from my own and that of my family. There are always varying degrees of similarity and difference between myself and the people I interview, and collaborative projects like Driving Canada help emphasize similarities. The project also affords us an opportunity to talk about the challenges and contradictions in the immigration system of seeking high levels of education from migrants, while not always acknowledging credentials.

The project Driving Canada: a front seat view of immigration through Uber emerged after a series of preliminary conversations, and the signing of a formal collaboration agreement, a process that involved Museum staff from several departments. Qissa, in consultation with the CMIP, was responsible for project outreach and conducting pre-interviews with possible participants. Some of the people who participated in a pre-interview decided not to participate in the recorded interview, for different reasons, but the stigma of being seen as an ‘Uber driver’ came across as a primary deterrent. The pre-interviews help with the process of building informed consent in oral history, where potential interview participants learn about the project and the group or institution behind it, and share elements of their life experiences and migration stories in preparation for an interview.

The Interviews

Haroon, Anam, Emily:

Taken together, the interviews help us understand first-person experiences of newcomers facing employment challenges and systemic barriers in a major urban centre—and crucial receiving area for new arrivals in Canada—while also seeking opportunities and building lives in Canada. All eight interview participants migrated to Canada between 2018 and 2024. Five are of Indian origin, two of Pakistani origin, and one person is from Syria. All interview participants have a bachelor’s degree, and five have master’s degrees. Subject areas include anthropology, Arabic, computer applications, information technology, and pharmacy.[5]

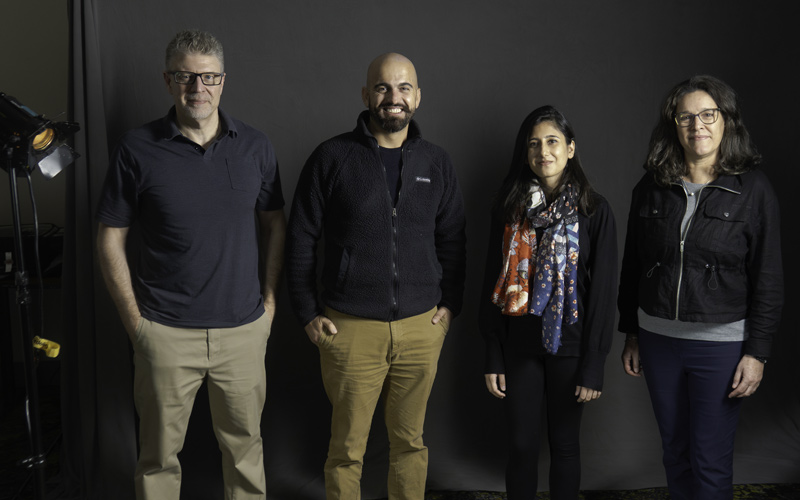

We conducted seven interviews in Toronto, with Darryl Leblanc as the videographer.[7] Each interview was about an hour and a half long. Anam and Haroon were the interviewers for six of the oral histories, and Emily interviewed Anam and Haroon together, as the last interview (about three hours long) to provide broader context to the project. Here is a bit more information about individual interview participants:

Kulbir Singh, a Sikh-Marathi immigrant and former Microsoft professional from India, moved to Canada in 2024, driving Uber for up to 19 hours a day to support his family while struggling with fatigue and separation from his daughter. Mehakjot Singh, a Punjabi immigrant with a post-graduate degree in pharmacy, arrived in 2019, working factory shifts before securing a logistics job, while continuing to drive Uber to supplement his income. Rammah Mohammad came to Canada as a refugee from Syria and is an award-winning musician. He turned to Uber for financial stability after struggling to secure steady employment despite earning a diploma in community services. Yalgar Singh is an IT professional from Punjab who moved to Canada in 2022, navigating underemployment before securing a full-time transit job. Niharika Aggarwal is a data analytics professional. She struggled to find work after immigrating in 2022, but was eventually able to join the Canadian office of her Indian employer. Mohd Javed Khokar, a Mumbai-born pharmacy graduate, switched fields due to visa delays, balancing studies and work before transitioning from Uber to a job aligned with his skills after gaining Permanent Residency in 2023.

Reflections And Outcomes

Haroon:

As recent immigrants ourselves and having spoken with so many others, there were aspects of the interviews that were not surprising at all. We anticipated that they would likely talk about the undervaluing of their international education and experience.

However, something that surprised me was the incredible vulnerability that many of these immigrants experienced. With limited financial reserves, and sometimes even borrowed money, a lot of newcomer immigrants do not have the ‘luxury’ of time to get additional diplomas, take courses or volunteer, so that they have something ‘Canadian’ to show on their resumes. Time acts as a barrier for many, even to wait to get a job commensurate with their backgrounds. This vulnerability forces several newcomers into the gig-economy.

While Uber was a choice borne out of necessity for all of the participants, a highlight from all the interviews was how several participants used this situation to enhance their professional skill. For example, Mohd Javed Khokar spoke about how he used his Uber experience to brush up on his communications skills. Kulbir Singh talked about how he brought his experience of customer services into Uber, ensuring that his passengers have the best experience they possibly can. Mehakjot Singh used this opportunity to learn more about the different cultures and histories, while Yalgar Singh used his experience to get an insight into the work culture of Canada. It was truly heartwarming to see how several participants made the best out of their situation.

Anam:

There were many themes and experiences that emerged from these interviews that reinforced my earlier understanding of the systemic barriers newcomers face. At the same time, there were other aspects to these stories that showed me how much more complex immigrant experiences were. The impact of COVID-19 on visa applications, processing times and on people’s decisions about wanting or not wanting to come to Canada showed the importance of conducting oral history interviews at particular moments in time. These issues came up in the interviews of Yalgar and Niharika Aggarwal. Mehakjot’s story of separation from his child spoke of the emotional cost of immigration. Stories of turning to Uber to have more control and flexibility over one's life disrupted my own preconceived notions of what driving Uber meant to highly skilled immigrants, as was the case for Rammah Mohammad and Mohd Javed. The larger impact of macro events like economic recession and the precarity of the gig economy, including its shifting policies and rules, also pointed to the vulnerability of the drivers. Ultimately this was an experience of humanizing folks who drive for Uber around the city, including immigrants who quite literally drive Canada.

While the interviews were often very heavy and emotional, I really enjoyed the lighter moments both during but also before and after the interviews. One particular moment was watching the back and forth between Niharika and Yalgar, a couple we interviewed separately. They knew each other in another lifetime, both ambitious students in Punjab, India. They met again in Canada when they were both struggling to land a job, and when Yalgar was still driving Uber. Navigating the loss of community, Niharika and Yalgar found community in each other, eventually getting married. Their story was such a poignant glimpse into the intimacy between the personal and political and a reminder that life stories are never linear or one-dimensional.

Emily:

It was a rewarding experience to be able to interview Anam and Haroon as fellow oral historians, and also to observe the interviews conducted by them. The rapport between them and the people interviewed, including sometimes speaking in Urdu/Hindi and Punjabi before and after the formal recorded interviews, helped create a welcoming atmosphere for interview participants, and confirmed the benefits of collaboration based on shared experiences.

The interviews have all been added to the CMIP’s permanent oral history collection. The collection helps document first-hand experiences of people who have come to Canada as refugees, migrants and immigrants, as well as people who work in immigration-related areas. The interviews, subject to restrictions, are available to both the CMIP and Qissa, and potentially other external researchers as well, to learn from, and possibly create additional content, including exhibitions, public programs, videos, articles and so on.

Conclusion

We have now finished this phase of the project collaboration, which focussed on the outreach and interview recordings. Thank you to all the interview participants for so generously sharing your stories with Qissa and the CMIP, and through us with the Canadian public! Thank you also to CMIP staff who facilitated the collaboration in various ways.

Filtered through different institutional and interpretive lenses, we may each have subsequent phases of the project in which we draw out different threads from the interviews, and in the process take different paths.[9] We may also decide to collaborate again in a joint project of making meaning from the interviews, with each other and possibly with the interview participants, but the structure of the project also allows us to each pursue this independently.

Stay tuned!

- Rammah Mohammad, interviewed by Anam Zakaria, 25 October, 2024 in North York, Ontario. CMIP in collaboration with Qissa (24.10.25RM): 01:27:55.↩

- Yalgar Singh, interviewed by Haroon Khalid, 26 October, 2024 in North York, Ontario. CMIP in collaboration with Qissa (24.10.26YS): 01:18:55.↩

- For an overview of past CMIP collaborations in oral history, see: https://pier21.ca/blog/emily-burton-phd/collaboration-oral-history-research↩

- Photographs from interviews: Kulbir Singh; Mehakjot Singh with Haroon, Anam and Emily; Mohd Javed Khokar.↩

- Qissa, “Driving Canada: A Front Seat View of Immigration through Uber. A project by Qissa in collaboration with the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21,” 2025.↩

- Photographs from interviews: Yalgar Singh; Yalgar Singh and Niharika Aggarwal with Haroon and Anam; Niharika Aggarwal.↩

- Mehakjot Singh, interviewed by Anam Zakaria, 25 October, 2024 in North York, Ontario. CMIP in collaboration with Qissa (24.10.25MS); Rammah Mohammad (24.10.25RM); Yalgar Singh, (24.10.26YS); Naharika Aggarwal, interviewed by Anam Zakaria, 26 October, 2024 in North York, Ontario. CMIP in collaboration with Qissa (24.10.26NA); Mohd Javed Khokar, interviewed by Haroon Khalid, 27 October, 2024 in North York, Ontario. CMIP in collaboration with Qissa (24.10.27MJK); Kulbirsingh Bhullar, interviewed by Anam Zakaria, 27 October, 2024 in North York, Ontario. CMIP in collaboration with Qissa (24.10.27KSB); Anam Zakaria and Haroon Khalid, interviewed by Emily Burton, 28 October, 2024 in Toronto, Ontario. CMIP in collaboration with Qissa (24.10.28AZHK).↩

- Photographs from interviews: Rammah Mohammad, Rammah Mohammad with Darryl LeBlanc, Anam and Emily; Haroon, Anam, and Emily.↩

- The Museum aims, in every oral history project, to build the collection for both current use and future generations, so collaboration beyond the interview phase may or may not be part of a collaborative project.↩