by Steve Schwinghamer, Historian

(Updated January 28, 2022)

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (DI2013.1197.1)

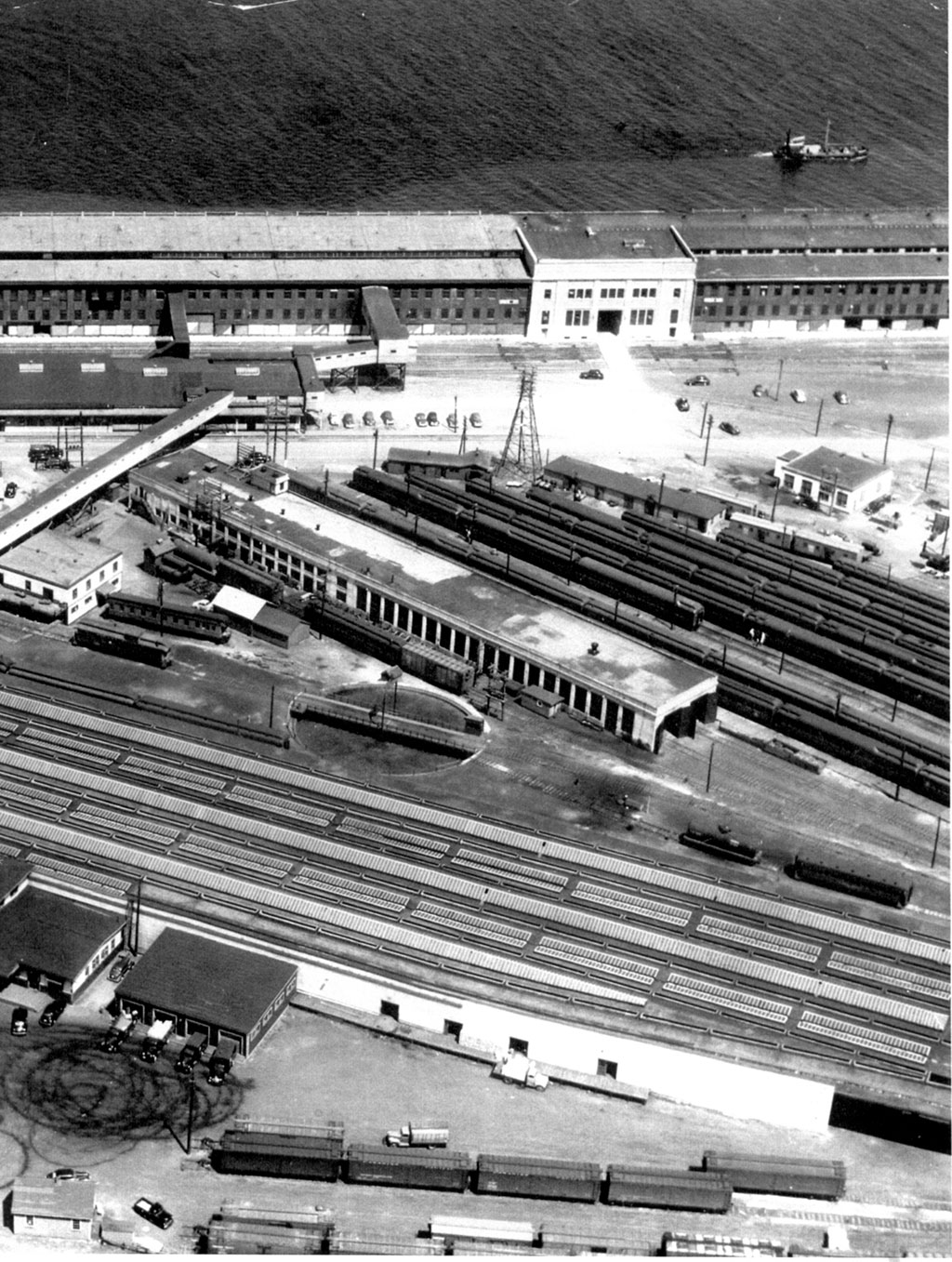

As Canada prepared for war in late 1939, the advantages of Halifax’s port were considered of value for military purposes. Halifax harbour was large and deep, ice-free and close to Great Circle shipping routes from Europe to the Eastern Seaboard of North America.[1] In addition, the city was linked to the transcontinental rail system.[2] Halifax’s immigration facility, Pier 21, was designed to handle the passengers and cargo of large ocean liners, and so could also accommodate the same vessels as troopships. With the outbreak of war in September of 1939, the Ocean Terminals complex in Halifax’s South End, including Pier 21, was put to use under the oversight of the military to support both civilian and military traffic. This switch in roles echoed that of Pier 21’s predecessor, the facility at Pier 2, which had been used for military logistics during the First World War.[3]

Civilian Traffic

Canada continued to welcome an average of almost 13 000 immigrants per year during the Second World War, only a slight drop from admissions during the Depression.[4] Until significant movements of soldier dependents began in 1944, the majority of immigrants were citizens of the United States, presenting themselves at the land boundary rather than arriving by sea.[5] Wartime immigrant entries included a steady trickle of immigrants who were not ordinarily acceptable under the highly restrictive policies enacted during the Great Depression. These entries had to be sanctioned by Orders in Council.[6]

This modest ocean immigration traffic was not demanding on the resources at Pier 21. However, the perceived dangers of war brought another notable type of the civilian traffic through Pier 21 during the Second World War: the humanitarian evacuation of children to Canada from the United Kingdom. Adrienne Downs was brought to Canada for safety as a nine-year old girl in 1940, and she recalls that she “was so excited over this big adventure which I thought would just be a holiday.”[7] Underneath this adventure, however, was a grim fear of the danger of aerial bombing to civilian populations. In September of 1939, almost 1.5 million civilians were on the move in the United Kingdom, evacuating from major cities to rural areas to seek safety based on planning begun the year before.[8] To February of 1941, evacuated civilians included almost 6000 privately- and publicly-funded children, and about 2000 adults.[9] Some estimates place the total number of wartime civilian evacuees to Canada at over ten thousand.

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (DI2014.535.1a)

Another major group entering Canada during and just after the war were the dependents of Canadian soldiers. This group included women married to Canadians abroad during the war, known as “War Brides”, and the children of Canadian soldiers born abroad. This was the largest coherent movement of immigrants to pass through Pier 21: 64 446 women and children came to Canada as soldier dependents from 1942 through 1948.[10] The vast majority traveled by way of Pier 21, although some arrived by way of other ocean ports or by air travel. Beyond the mechanics of the administered system for soldier dependent transport, there were a notable number of military marriages that were unreported, after which private transportation arrangements were made.[11]

Halifax’s immigration staff spent a great deal of time resolving the wartime cases of foreign merchant mariners. Arriving ships might have a crew that included allies, neutrals and enemy nationals. Crew might disembark legally, desert or be brought in as survivors of a sinking. All of these factors, together with the strict regulations governing immigration and service in the merchant navy during the war, made substantial work for the immigration office. One administrator in the Pier 21 office claimed that they handled forty percent more files early in the war than in average peacetime years preceding the conflict.[12] The merchant mariners were often in circumstances that required accommodation or detention, and those who refused shipping assignments could find themselves confronted by local authorities. In 1940, seamen held at the city jail for rejecting shipping assignments demanded to be held at the immigration quarters instead.[13] Throughout the war, the accommodation and detention area remained busy with merchant seamen, although rarely was it as crowded as in March of 1942, when the immigration quarters held more than 170 seamen.[14]

Another group of civilians entered Pier 21 during the war, although they were unexpected even in the tightly regulated wartime transit environment: German refugees sent to Canada intermingled with a movement of prisoners of war from Britain. Prepared for 7000 hardened enemies, Canada received only 3000. However, they were sent alongside, and without distinction from, 2500 German civilians, many of whom had fled from persecution in Germany.[15] Many of these civilians were released during the war; others benefited from a substantial change in their living conditions in 1941. For instance, in Sherbrooke, Quebec, the internees established junior and senior grade schools, an engineering faculty, vocational training, professional musical performance instruction, and other programs. They co-ordinated accreditation and exams with other camps and with McGill University, among other institutions.[16] It is perhaps one of the most absurd episodes of the war, but the “accidental” internment ended well for many, with about 1000 of the civilians eligible for and accepting naturalization in Canada after the war.[17]

To conclude with regard to civilian traffic, there were a small number of people who entered Canada on the strength of diplomatic or professional demands. For example, in July of 1940 Polish government staff and some family members entered Canada via Halifax on diplomatic or service passports, along with classified wireless equipment and an operator to help co-ordinate the diplomacy of the Polish government-in-exile. This was preceded by a request for their entry by the Consul General of Poland in Canada to the Department of External Affairs.[18] Similarly, in June of 1940, immigration staff attended the arrival of Princess Juliana of the Netherlands and her children in Canada via Halifax, albeit not directly at Pier 21.[19] Finally, Winston Churchill made several trips to Canada during the war, including one in August of 1943, when he arrived at Pier 21 aboard Queen Mary.[20] These cases underscore the variety and significance of civilian movements encountered by Halifax’s immigration staff during the Second World War.

Military Personnel

Credit: NS Archives H.B Jefferson Collection, 1992-304 / 43.1.4 250

The broad scope of civilian traffic at Pier 21 during the Second World War is often overshadowed by the scale of military movements through the site. Halifax’s Ocean Terminals were used as a primary embarkation point for Canada’s service personnel headed for service in Europe during the Second World War.[21] About 368 000 military personnel passed through the Ocean Terminals complex, including Pier 21, during and just after the Second World War. In 1942, over the course of three months, almost 60 000 soldiers embarked at the Ocean Terminals for service overseas.[22] The importance of the site for military movements was recognized during the war. Celebrities such as singer Gracie Fields participated in events at the Embarkation Unit or aboard ship.[23] At other points, bands played to bid farewell or welcome personnel home.[24] Despite the local fanfare, security was tight around these movements during wartime.[25] After the war, returning soldiers were greeted with fanfare and exuberant press. Sometimes children in the city would run down to meet the ships, although their motives might be less than patriotic or sentimental. John Connolly remembers counting the stacks on the ships coming in, and if it was a large vessel, he and his friends would go to the brow of the piers at the Ocean Terminals,

“[n]ot so much to welcome the troops back, but to say, "Throw us some money," and they would throw the English coins overboard, or over the ship, which would land on the cement dock and bounce all over. Whichever kid was the fastest, the toughest, the roughest, we’d get the most coins by pushing the others out of the way.”[26]

The return for many Canadian service personnel was more sombre: the Embarkation Transit Unit at the Ocean Terminals also served hospital ships that repatriated wounded Canadians. Victor Gray, a bandsman and stretcher-bearer who worked at the Embarkation Unit regularly, reflected on seeing “a young lieutenant being taken off by two other soldiers, him in the middle, and them with his arms around their shoulders, holding on to him, and dragging his feet, right out of it completely with shell shock.”[27]

Although the main job for military personnel stationed at the Ocean Terminals was embarkation, there were others supporting this task. A band and local transport units all worked regularly out of the area of Pier 21 and the Annex.[28] There were barracks in the Annex building, and a military unit was briefly barracked in the immigration facility’s Assembly Hall.[29] Military medical personnel complemented the existing Department of Health and Welfare staff, adding a medical inspection room and a dispensary to support military personnel at the terminal. Finally, personnel also made use of the large waiting spaces in the Annex while waiting for trains.[30] This continued until 1944, alongside normal immigration operations.[31]

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (DI2014.536.1)

On 5 March 1944, a major fire swept through Pier 21, gutting the immigration quarters and causing an estimated $250 000 in damage. The fire was traced to fumigation equipment used by the Department of National Defence’s Embarkation Unit to clean ship’s bedding in Pier 22.[32] The Immigration Department took up residence in the Annex Building and in temporary wooden sheds nearby while shed 21 was repaired.[33] Although Army personnel immediately undertook the task of clearing loose debris, the damage was profound: the National Harbours Board described the second storey of the shed as “almost entirely destroyed” and sought contracts for its complete demolition as the first step in repairs.[34] Pier 21’s second storey immigration quarters did not reopen until December of 1946.[35] The Embarkation Unit continued to operate from temporary buildings near the Annex, from the Annex itself and out of the waterfront sheds until 1947.[36]

Pier 21 and the Ocean Terminals were crucial for the transportation of Canadian service personnel, but members of the armed services of allied nations passed through as well. One of the major Canadian contributions to the war effort was its participation in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), an organization with more than one hundred schools and employing more than 100 000 Canadian personnel throughout the war. Over the duration of the conflict, almost 60 000 personnel trained in Canada through this program for the air forces of Great Britain, New Zealand and Australia. Among these were Polish, Norwegian, Belgian, Dutch, Czech and Free French allies serving in the Royal Air Force (RAF).[37] The core of the teaching personnel for this plan, eighty-five experienced RAF members, arrived at Pier 21 in January of 1940; more followed to a total of about three hundred experts.[38] Pier 21 and the Ocean Terminals continued to serve the BCATP as its only significant ocean embarkation depot through the duration of the plan.[39]

The movement of military personnel through Pier 21 during the Second World War also included enemy prisoners of war. The prisoners joined trains immediately to go to detention camps further inland.[40] Many of the prisoners provided valuable labour in Canada, such that at the end of the war, a movement of veterans of service in Polish forces was conceived to replace them. Public messaging of this replacement of enemy prisoner labour by largely allied veterans was delicate, and drew considerable attention within the immigration department.[41] Nevertheless, one of the signal outcomes of the transit and internment of the prisoners of war in Canada was this follow-up, which was in turn an important leading movement in Canada’s post-war acceptance of displaced persons and refugees via bulk labour arrangements.

Conclusion

Halifax was a major strategic port during the Second World War. Part of the key infrastructure in Canada’s war effort was the Ocean Terminals facility, including Pier 21. The combination of the capacity to serve several ships at once and immediate access to the railway made the terminal an important transportation nexus. Alongside the military embarkation unit, Pier 21 continued to operate as an immigration facility during the Second World War. Although the annual rate of immigration was very low during the war, the immigration authorities dealt with many other kinds of cases, including evacuated civilians, refugees, foreign service personnel, and merchant mariners from all over the world.

(For information on cargoes sent via the Ocean Terminal during the Second World War, see my prior blog entry on the Wawel Treasures.)

- James D. Frost, “Halifax: The Wharf of the Dominion, 1867-1914”, Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society Journal, 8 (2005), 35.

- William Naftel, Halifax At War: Searchlights, Squadrons and Submarines, 1939-1945 (Halifax: Formac Publishing, 2008), 12.

- J.B. Hunter, Deputy Minister, Public Works, to G.A. Bell, Deputy Minister Railways and Canals, 5 November 1920, in Department of Immigration, “Immigration Building – Halifax, NS”, Library and Archives Canada, RG 76 Volume 666 File C1594, Part 1

- Statistics Canada, Historical Statistics of Canada, Immigration: Immigrant Arrivals in Canada, 1852 to 1977 (Table A350), http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11-516-x/sectiona/A350-eng.csv

- Dominion Bureau of Statistics, The Canada Year Book, 1945 (Ottawa: Edmond Cloutier, 1945), 168; Dominion Bureau of Statistics, The Canada Year Book, 1946 (Ottawa: Edmond Cloutier, 1946), 185.

- Department of Mines and Resources, “Orders in Council – Immigration Branch, 1940-1945”, Library and Archives Canada RG 26 Volume 87

- Adrienne Downs, interviewed by Steven Schwinghamer, 2 July 2002, Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Oral History Collection, 02.07.02AD, 00:07:03ff.

- Judith Tydor Baumel, “Twice a Refugee: The Jewish Refugee Children in Great Britain during Evacuation, 1939-1943”, Jewish Social Studies, 45:2 (Spring 1983), 175

- Department of Citizenship and Immigration, “Evacuees to Canada, 1940-1941”, Library and Archives Canada RG 26 Vol 16 (no file number)

- Melynda Jarratt, The War Brides of New Brunswick, (University of New Brunswick, Masters Report, 1995), p. 12, accessed via http://www.canadianwarbrides.com/thesis1.asp

- Department of National Defence, “History of Special Assistant to the Adjutant General Office and Directorate of Repatriation, 1942-1947”, Library and Archives Canada RG 24, HQS 8536-1, 34.

- Fenton Crosman, “Recollections of An Immigration Officer: The Memoirs of Fenton Crosman, 1930-1968”, No. 2 in Perspectives on Canadian Immigration (Ottawa: CIHS, 1989), 128

- Crosman, “Reflections”, 130.

- Crosman, “Reflections, 161-162.

- Ernst Koch, Deemed Suspect: A Wartime Blunder (Toronto: Methuen, 1980), xv

- Koch, Deemed Suspect, 151

- Koch, Deemed Suspect, 255

- Victor Podoski to William Lyon Mackenzie King (as Secretary of State for External Affairs), 11 July 1940, in Department of External Affairs, “Entry into Canada of Polish officials, art treasures and radio equipment”, Library and Archives Canada, RG 25 Volume 2803 File 837-40

- Canadian Press, “Princess Juliana and Children Land in Halifax”, Halifax Mail, 11 June 1940, 1, 5; Alison Trapnell, interviewed by James Morrison, 16 April 1998, Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Oral History Collection, 98.04.16AT, 00:52:31ff

- H.B Jefferson, Journal, August 1943, Nova Scotia Archives 1992-304 489 A, accessed via http://novascotia.ca/archives/virtual/eastcoastport/archives.asp?ID=341&Page=200900592

- Naftel, Halifax At War, 82-83.

- Parks Canada, “Backgrounder: Pier 21, Halifax”, updated 26 September 2013, accessed 16 April 2014 at http://www.pc.gc.ca/APPS/CP-NR/release_e.asp?bgid=134&andor1=bg; Parks Canada, “Pier 21 Recognized as National Historic Site”, 17 August 1999, accessed 16 April 2014 at http://www.pc.gc.ca/APPS/CP-NR/release_e.asp?id=45&andor1=nr; C.P. Stacey, The Canadian Army, 1939-1945 (Ottawa: Edmond Cloutier, 1948), 1.

- Carrie-Ann Smith, “We’ll Meet Again: The Gracie Fields Story”, Web log, http://www.pier21.ca/blog/carrie-ann-smith/we-ll-meet-again-the-gracie-fields-story, accessed 17 April 2014

- Victor Gray, interviewed by Amy Coleman, 10 July 2001, Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Oral History Collection, 01.07.10VG, 00:04:53ff

- Joyce Woodford, interviewed by Amy Coleman, 28 May 2003, Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Oral History Collection, 03.05.28JW, 00:08:59ff

- John Gerald Connolly, interviewed by Steven Schwinghamer, 5 July 2000, Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Oral History Collection, 00.07.05JC, 00:01:46ff.

- Gray interview, 00:14:30ff

- Naftel, Halifax At War, 84-86.

- Canada Employment and Immigration Commission (CEIC), “The Pier 21 Story, Halifax: 1924-1971”, unpublished report, 17; “Fire-Gutted Pier Had Colorful History”, Halifax Mail, 6 March 1944, 1, 3, 13

- Woodford interview, 04:40ff

- Crosman, “Reflections”, contains useful commentary on wartime operations in Halifax.

- “Fire-Gutted Pier Had Colorful History”, Halifax Mail, 6 March 1944, 1, 3, 13; National Harbours Board, Minutes of Meeting Held at Ottawa, 1 May 1944, in “National Harbours Board Minutes of Meetings 1936-1945”, Library and Archives Canada RG 66 Box 23 No 83-84/130

- “Fire-Gutted Pier Had Colorful History”, Halifax Mail, 6 March 1944, 1, 3, 13; Trudy Duivenvoorden Mitic and J.P. LeBlanc, Pier 21: The Gateway that Changed Canada, (Halifax: Nimbus, 1988), 73

- National Harbours Board, Minutes of Meeting, 1 May 1944

- Mitic and LeBlanc, 73.

- CEIC, “Pier 21 Story”, 18.

- Veterans Affairs Canada, “The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan”, Web site, http://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/history/second-world-war/british-commonwealth-air-training-plan

- F.J. Hatch, The Aerodrome of Democracy: Canada and the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, 1939-1945 (Government of Canada: Ottawa, 1983), 37.

- Hatch, Aerodrome of Democracy, 208.

- Naftel, Halifax at War, 92-94.

- For the body of this discussion, see Department of Immigration, “Admission of 4000 former Polish soldiers for agricultural work in Canada”, Library and Archives Canada, RG 76 Volume 648 File A85451