A man drives down Terminal Road towards Pier 21. He is wearing a blue shirt; next to him his wife holds a bouquet of flowers. He is nervous and excited. He is coming home in a sense and he cannot stop thinking about what brought him to Pier 21 the first time, all that had happened before and all that has happened since.

A woman stands in the foyer of Pier 21 National Historic Site. She is wearing a navy blue, slightly military style jacket and studying everyone as they walk through the doors. He said that he would be wearing a blue shirt. How is it that on this, an uncommonly busy day, every man who enters is wearing some variety of blue shirt? She glances at the time, watches and waits.

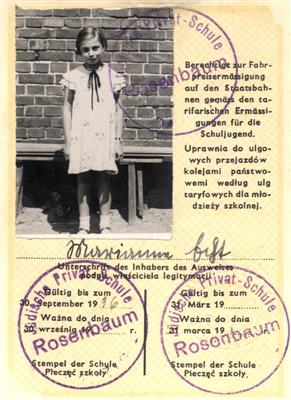

When Marianne Ferguson (nee Echt) was a young Jewish girl in 1939, her family had the remarkable good fortune of escaping from the Free State of Danzig (now Gdansk, Poland) before the Holocaust. As both a pharmacist and a hobby farmer her father was uniquely qualified to become one of the mere five thousand Jews given permission to enter Canada during the Hitler years.

Once her family was living peacefully in the Nova Scotian countryside a sixteen-year-old Marianne decided to record her memories of growing up in Broesen and of her family’s escape. Her account details the transformation that occurred in that summer resort town where she spent an idyllic childhood.

The Echts were leading citizens in the community of 4,000. There was one church in the town and though the Echts, as Jews, were not members they were invited to all special services and parties that their Christian neighbours held. Her parents did charity work. They had a beautiful home and garden that were always filled with friends and relatives. In the summer they had frequent guests who came to enjoy the beach, park and good company in the pretty seaside town.

All of this changed when Hitler became Chancellor of Germany in 1933. Jews, Marianne writes, were not even allowed to visit the beach or walk in the park. She notes that although ninety percent of the people of Broesen weregentiles, most were anti-Nazi and would have resisted if any attempt had been made to hurt her family; but the good people of Broesen would not be exempt from the madness engulfing the world outside their little town.

There were Nazis in the town but they would not risk the wrath of their neighbours, so the government sent in Nazis from other towns. Marianne writes, "These men came at night, broke the doors and windows of some of the people's houses, and brought the head of the family to a place which was unknown to all other people. The next day, the family of such persons would get a little gift. This gift consisted of a dainty, little parcel, mostly a box, wrapped in tissue paper and tied with a brightly colored ribbon. When it was opened, one found in the box the remains or ashes of the person of the family which had disappeared the night before. Also a little card was enclosed, a card of sympathy."

Marianne recalls a shocking incident in which the minister of the local parish found on his doorstep two halves of a cat on a gallows, accompanied by a note which said, "Today the cat, tomorrow you.'" The same minister found his chicken-house robbed with a note reading, "God is everywhere, but not in the minister's chicken-house" posted on the wall.

Her father knew that it was time to get out. There were strip-searches, threats and questions, but they were finally able to leave. After tearful goodbyes with relatives the time came for the Echt family to leave for Canada. For Marianne and her sisters this departure was both cause for optimism and heartbreak. Marianne writes, "Everyone asked us to take them with us, but that was impossible."

At the same time in the town of Sandomierz, one of the oldest Jewish communities in Poland, eight-year old Nathan Wasser was sitting at his grandfather's feet. There were no happy bedtime stories for the little boy; instead his grandfather was teaching him lessons that he feared the boy would need. It was going to get worse for the Jews before it got better and he would not always be there. "Sleep with one eye open", his grandfather warned, "Be aware of everything that is going on around you, analyze, comprehend, find solutions." Over and over his grandfather reinforced, "analyze, comprehend, find solutions" and taught Nathan that he had to be able to do all of that in a split second. To this day Nathan Wasser remembers the exact words of the warnings, and credits his grandfather with saving his life when so many around him fell.

The Wasser family survived three ghetto liquidations and two slave labour camps before being sent to Auschwitz and what they thought was certain death. They had already been separated from two of their sons and feared for the two children that they had with them. Everyday brought new challenges to their survival. Upon arriving in Auschwitz the Wassers were miraculously reunited with their son Kopel who gave them instructions on how to survive in the camp. In Auschwitz prisoners declared 'unable to work' were sent to Birkenau to be killed in the gas chambers; healthy workers would be sent from Auschwitz to the slave labour camps. At inspection time Nathan, now thirteen-years-old, threw back his shoulders, stuck out his chest and willed himself to look bigger. It worked and he, his father and uncle all made the forced march to Glavitz #1.

Nathan’s brother, Leibchu Wasser had found a way to stay behind in Poland and hide in the underground. Nathan’s mother and sister Helen were sent to a different camp and Nathan lost touch with them. It would be a long time before he would know that for his mother there would be no liberation, no reunion, no ship on the North Atlantic.

In April of 1945 Nathan’s sister and mother were traveling aboard a train that was bombed. The Wasser women survived, crawled out of the wreck and walked to a neighboring farm. The next morning Nathan’s sister and two other survivors went into town hoping the Russians would give them passes allowing them to go home. While they were in the town the German’s discovered the hiding place where the others had stayed behind and threw grenades into the farmhouse killing everyone.

Mrs. Wasser would travel to Canada only in the hearts and minds of the survivors.

The Echts settled in Nova Scotia in late 1939 and bought a farm. Marianne and her sisters went to school, learned the language quickly and made friends. The family rejoiced in their freedom and new community but were always aware of those they had left behind. They did everything they could to gain permission to bring their relatives to Canada, but no promise of sponsorship or employment would soften the uncompromising stance of the Canadian government. In 1946 word reached the Echt family that there was no family left in Europe to try and save. The last letter they received was telling. It explained that there were no more ships leaving - it had been written hastily in a park in Hamburg where their aunts, uncles and cousins were gathered just before they were picked up by the Gestapo and taken to Auschwitz where they perished.

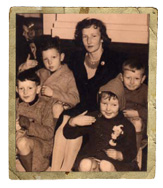

It was too late to help them, but there was still good that could be done. The Echt family had been welcomed to Canada at Pier 21 by Sadie Fineberg of the Jewish Immigrant Aid Society. Sadie had become a close friend of the family so when she was appointed as a representative of the Mayor of Halifax Meta Echt assumed her role and became the representative of the Jewish Immigrant Aid Society. Marianne’s younger sisters were still in school but she would be her mother’s constant companion at Pier 21.

It was early September of 1944 months before Nathan’s arrival in the labour camp when American bombers destroyed large parts of the 'Oberschlesische Hydrierwerke AG' in Blechhammer and the oil refinery in nearby Trzebinia. It had to be a good omen. The end of the war had to be near.

The Wassers worked and survived in Glavitz. In early January 1945 they were forced to make another death march, this time to Blechhammer. With only a little bit of bread the prisoners had to walk for days; many died of exhaustion and hunger or were shot by SS officers but still the Wassers survived. By the time the Wassers reached Blechhammer Labour Camp they could barely stand.

The day after their arrival a Russian bombardment ensued with many bombs falling on the camp. Luckily a bomb pierced one of the camp’s retaining walls and Nathan and his father were able to escape. They fled to the forest and with the help of the Russian Army, survived the final days of the war.

At this stage in his young life Nathan wanted only to find the rest of his family, to go back to school and to spend his life in the Poland that he loved, the Poland of his boyhood, his grandfather's Poland.

When Nathan and his father returned to Sandomierz they did not find Leibchu waiting for them as they had expected. Betrayed by his Polish school friends from the underground, Leibchu had been murdered by those that he trusted the most. As devastating as the loss of his beloved brother was, more sadness was to come and there would be an inconceivably evil event that would compel his departure across the sea.

By 1947 when Canada began admitting Jewish war orphans and large numbers of displaced persons, Meta Echt and her daughter worked long hours in the immigration shed. Marianne, now a young woman, had married Lawrence Ferguson, Sadie Fineberg’s nephew.

In time one hundred thousand refugees would come to Canada; many of them would remember the volunteers who aided and reassured them - Sadie with the bread and kleenex that she brought from her husband's dry goods store, Meta and Marianne with their smiles and kindness. For Marianne every face she saw could have been one of her relatives and she lavished all of the love that she had for them on the lucky strangers who survived and made it to Canada.

In 1945 good fortune finally called on Nathan and his father, Helen Wasser found them and the reunited trio found Kopel who had just been released from an American military hospital. Helen told her father and brothers what had happened after the train was bombed. They grieved together and then the little family set out to look for other relatives and friends.

When originally interviewed, Nathan Wasser simply said, "When we reached Kielce they had a party for those of us who returned." It was almost a month before he telephoned to explain what he had meant. For months the Wassers had observed the post-war horrors occurring in Poland as Jewish survivors of the Holocaust attempted to reclaim their homes. Murder was common and survivors frequently realized they were not wanted in their birthplaces and that if they did not leave willingly they would be forced out. The Wassers visited Kielce in 1945. They found no relations but felt the tension in the air, witnessed the abuse of fellow survivors and knew that they would not be safe there.

Anti-Semitism was fierce in the Polish town and it crystallized on July 4, 1946. A father in Kielce had told his young son to go to the next town so that he could claim the boy had been kidnapped and blame the repatriated Jews. In response to a fabricated story the community became enraged and started killing Jews. People of all ages participated in burning the synagogue and Jewish-owned homes. The police lured Jews out of their homes so that their neighbours could kill them. By three o'clock in the morning over forty people had been killed in the pogrom, including a Jewish mother and baby who were carried out of their house and murdered in the street. Seventy people were injured and countless others like Nathan Wasser would never be the same after learning of the incident.

This was no longer their Poland, if it ever had been. It was decided that Munich would be the first stop and then they would leave Europe for good. Nathan began attending school in Munich and quickly made up for the six years he had missed. Nathan went to the ORT centre for education and training and learned an electrical trade paving the way for his later success in Canada.

While Nathan studied, his father, with the assistance of a friend in the Canadian Jewish Congress, and relatives in Canada, organized their emigration. Although Nathan admits his father didn't know anything about the trade, he agreed to go to Montreal to be a furrier. Canada needed furriers, and like many refugees at the time, his father agreed to do whatever it took to get his children to Canada.

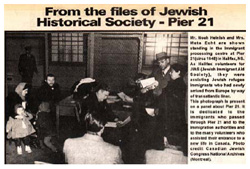

When Nathan Wasser finally arrived at Pier 21 he was seventeen years old, undernourished and frail-looking. He had been so busy with his studies and his preparation for Canada that he hadn't fully absorbed what he had been through, what he had lost and who he had become. It finally began to swirl in his mind when two women helped him up onto a counter at Pier 21, began feeding him candy, and told him that now, in Canada, everything was going to be all right.

There had been a problem with the currency he had procured on the black market in Germany before departure so one of the women gave him twenty dollars. He could not accept such generosity, how would he ever pay it back? Her words, "We trust you, we have faith in you, you are going to be a good Canadian citizen", hit him like a ton of bricks. Maybe it was their kindness, maybe there was something in the hug that the young woman had given him that reminded him of his mother. Whatever it was Nathan felt walls inside of him begin to crumble as Meta and Marianne Echt comforted him. Their time together was brief but he never forgot it.

The Wassers boarded the train and Nathan claimed a window seat. Beside the tracks the two woman stood blowing him kisses and waving goodbye. As the city and then the countryside passed his window Nathan put his forehead against the cool glass. The words began repeating themselves over and over in his mind, "We trust you, we have faith in you, you are going to be a good Canadian citizen." His voice cracks even now as he repeats them like a mantra. In those moments one life ended and another began; with a few kind words and a gesture of faith, Meta and Marianne had unknowingly given a young man the courage to look both backwards and ahead.

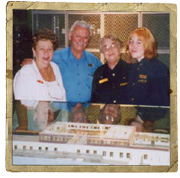

Now here he was, following the Halifax road that runs parallel to where the train tracks used to be. With his wife of forty-eight years at his side, he was going to repay a debt.

Months before Nathan had begun planning the trip to Halifax. Friends had given him the contact information of Jon Goldberg, Director of the Atlantic Jewish Council. It would be Mr. Goldberg that would hear Nathan's story and know by his descriptions that it was Meta and Marianne he sought. Meta Echt had since passed away but Marianne was not only still in Halifax but still volunteering at Pier 21, now in its most recent incarnation as a National Historic Site - walking the same halls where she and her mother had welcomed and comforted so many people like Nathan Wasser.

The foyer grows more crowded, women push strollers, children run up and down as men in shirts of every possible shade of blue file by. Then she sees him; he wears a blue shirt and holds a bouquet; there can be no mistaking him. They smile, walk towards each other, embrace and the crowded foyer seems to go silent.

Nathan presents Marianne with two cheques for the Atlantic Jewish Council; one is made out for “10 times double Chai” which represents life to the Jewish people and one for the original twenty dollars given to him by Meta Echt. Nathan Wasser is an elegant gray haired gentleman, a successful businessman, a family man, a good Canadian citizen. His debt, had there ever really been one, is repaid.

Note: After their reunion Nathan and Shirley Wasser accompanied Marianne into Rudolph Peter Bratty Exhibition Hall. Their tour guide, one of Pier 21’s summer students, was a pretty sixteen-year-old girl named Becky. Becky is Marianne’s granddaughter working at her first job. Marianne and Lawrence have three children and four grandchildren. Nathan and Shirley have three children and eight grandchildren. All are a living tribute to those who came before, the relatives huddled in the park, the mother and brother, the wise grandfather.