by Steven Schwinghamer, Historian

(Updated January 28, 2022)

In summer 2012, we offered an “historian’s tour” of our temporary exhibition, Shaping Canada: Exploring Our Cultural Landscapes. Rather than being a detailed tour of the exhibition in itself, the tour used parts of the exhibit as background to discuss the historical process at our museum. We took that approach for a couple of reasons. First, we want to be as transparent as we can about our work: as a public heritage institution, we’d like members of the public to be able to come and talk with us about how we think about the past and how we relate that to specific studies and exhibitions. Second, we think that practicing public history almost always entails a certain amount of teaching about the discipline itself. If we help our audiences extend their critical historical thinking, they may “read” our institution more deeply and be better able to participate with us in making meaning about the past. Finally, Canadians encounter public representations of our past everywhere! A structure of historical literacy lets us all make better decisions about what representations are well-founded and what may be dubious.

The first thing we should do is introduce our premises for our “historian’s tour”, including a definition of history: for our purposes, the discipline of history is the process of understanding change over time. People who work with making meaning out of this process are historians. That work happens in a variety of different settings: some historians work and teach in universities, others for professional research firms, provincial and federal departments or for museums and historic sites.

However, as historians, our process of approaching the past is similar no matter where we may be employed. That process is individual in some ways. For example, every historian has their own habits for writing or working in detail within evidence. Even though all of us have our own routines for personal work, the field of history does have a set of key principles that are essential for a responsible and fair approach to the past.

There have been many different efforts to make an exact and final list of those ideas, none of which has been embraced as authoritative. We’ve decided to follow a model created here in Canada: the Historical Thinking Project (more information at www.historicalthinking.ca). According to this model, there are six key concepts in critical historical literacy:

- Establish historical significance

- Use primary source evidence

- Identify continuity and change

- Analyze cause and consequence

- Take historical perspectives

- Understand the ethical dimension of historical interpretations

Each of the concepts lines up with a particular case study or research problem we dealt with during the development of Shaping Canada. We’ll be following this blog post with an entry on each concept as it relates to our exhibition. We hope, beyond thinking about our exhibition, that you can use these tools to critique other representations of the past. The past is often used to argue in the present, and these ideas may help you decide if you are being given a trustworthy and responsible historical argument.

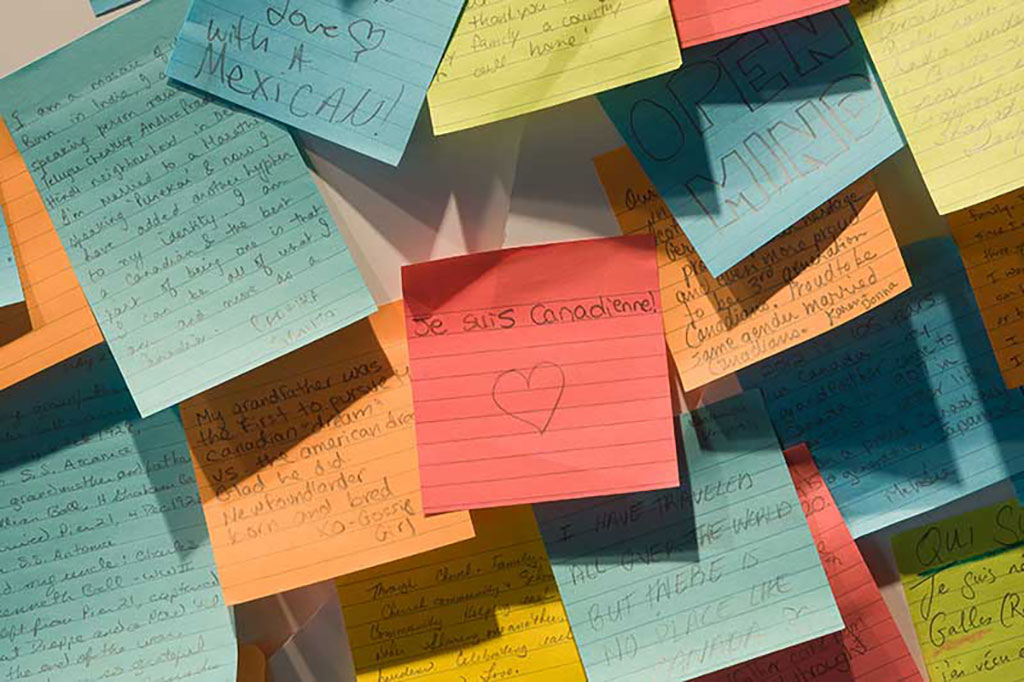

Some images of the Museum’s Shaping Canada: Exploring Our Cultural Landscapes exhibition.