by Steve Schwinghamer, Historian

(Updated January 28, 2022)

Perfect Landings was created by the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 to coincide with the Canadian Tire National Skating Championships in Halifax, to draw some of the guests interested in the event to the Museum, and to connect our existing visitors with other aspects of the city’s present and past. The basic theme of the exhibit is that figure skating in Canada has been profoundly influenced by the contributions of immigrants, as athletes, as coaches, and as builders of the sport and community.

Halifax is a great place to explore this topic. The local social and historical links to skating are significant. First, the production of millions of skates by Starr Manufacturing of Dartmouth in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The popularization of recreational and figure skating at the turn of the twentieth century was in part possible thanks to the availability of skates that actually stayed on people’s feet, and at the time, that often meant Nova Scotia’s innovative Starr skates. We are fortunate to have a pair in the exhibit, borrowed from the Nova Scotia Museum. Second, Halifax has hosted a few other major skating competitions over the past two or three decades (notably the Worlds in 1990) and so the competition here draws on a competitive legacy. Finally, skating has a fine history in Halifax’s Commons, linking back to the late 1800s, when people waltzed on ice in the Public Gardens. More recently, I think it is fair to say that the city has both surprised and delighted itself with the success of our outdoor oval, a wonderful and enjoyable legacy of the Canada Games that the city and citizens took up as a suitable use of the storied Commons of the city. (Aside: one of the builders featured in Perfect Landings is Joe Geisler, a German immigrant who arrived in 1927. He received the Centennial medal in part for his role organizing the first Canada Winter Games.)

These links form a good foundation, but still we might ask how an exhibit on figure skating came to be at the museum of immigration. The idea of this exhibit grew out of our experience some years ago hosting a temporary exhibit from the Canadian Museum of History, Lace Up!, which addresses the history of skating in Canada. It was apparent to us then, as we surveyed our collections and prepared to host the visiting display, that the development of the sport owed a great deal to the contributions and influences of newcomers. Once news arrived that Halifax would be the venue for another major skating event, we were happy to have the opportunity to explore that history and introduce it publicly – the result being Perfect Landings.

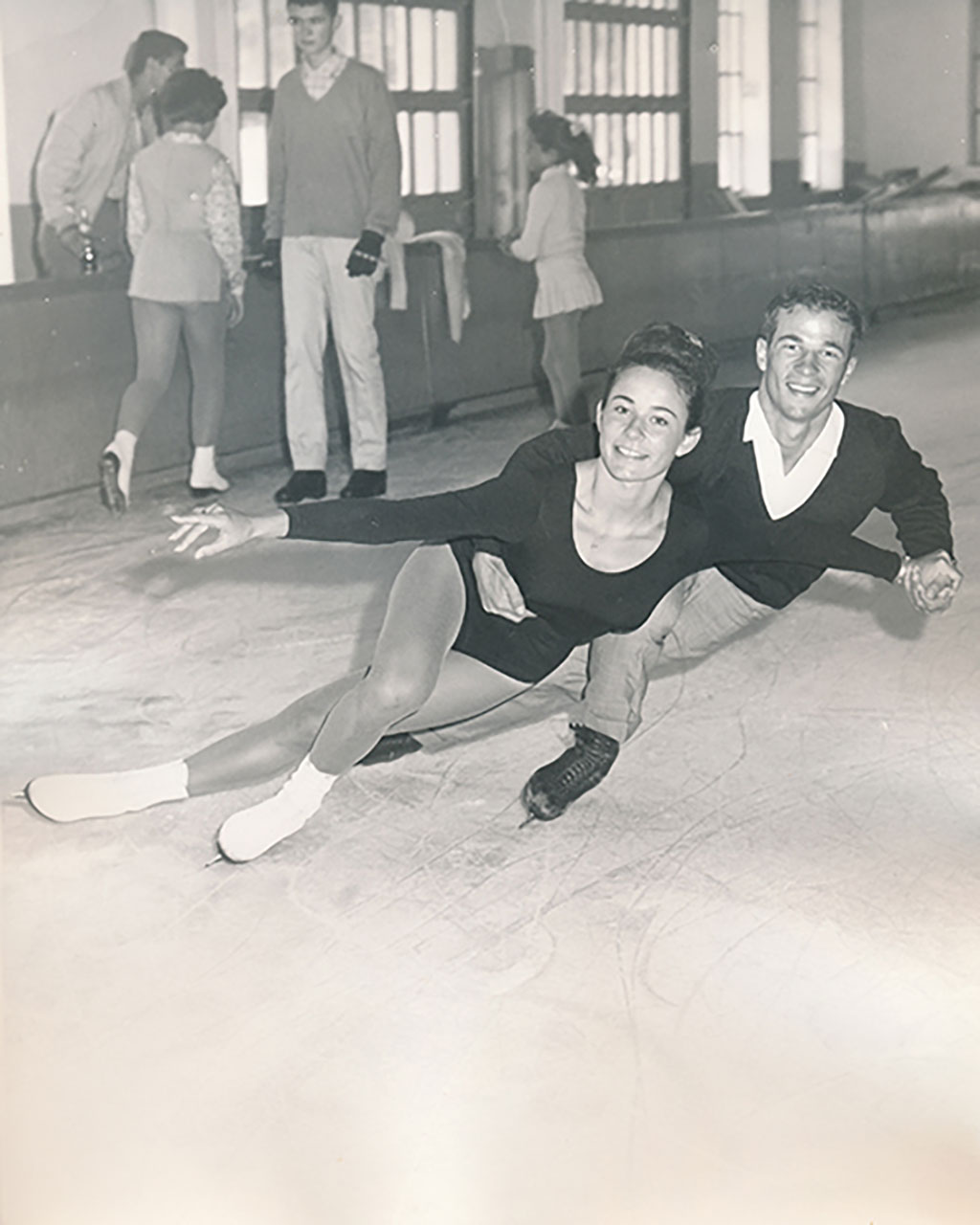

So, we have a fitting location. What can we point out as concrete evidence of the formative impact of immigration in the discipline of figure skating in Canada? After surveying the history, we find that the tools or equipment, the technique and style, and the training and professionalization of the sport, are all areas that have all been transformed by the contributions of immigrants. Regarding equipment, we could look to John Knebli’s role as a skate-maker to many of Canada’s premier athletes in the latter half of the twentieth century. Knebli’s story also has a particular weight in the place of the museum, as he first arrived in Canada in March of 1930 at Pier 21, as a passenger aboard Karlsruhe. On technique, the combined artistic vision of Ellen Burka (who arrived in Canada in 1951) and Toller Cranston is a fine illustration of integration and innovation—perhaps even disruption—in figure skating. Burka introduced a sensibility and aesthetic she sometimes termed “theatre on ice” to the performance of her skaters, a style developed out of her own broad artistic experience in the Netherlands. Finally, the professionalization of coaching in the sport owes a debt to the leadership of newcomers to Canada, such as Hellmut May. May visited Canada in 1954 to teach on a contract in New Brunswick and liked the experience, such that in 1955 he returned as an immigrant, bound for British Columbia. Besides establishing himself as the head coach of Kerrisdale Skating Club for more than fifty years, he also was instrumental in devising provincial and national coaching curricula. It is easy to think of more examples of leaders in the sport, including among those who were just here in Halifax, competing and contributing.

Credit: Skate Canada

Perfect Landings makes use of short biographical case studies to develop the connections between immigrants and figure skating. However, as an historian of immigration, I confess to an ulterior motive in my curation of the biographies. Through the lens of the personal stories in this small exhibit, we can access and explore some of the biggest issues in Canadian immigration history. Who is admissible to Canada? Why? How do they integrate? Are their credentials respected? What of humanitarian or ideological issues? How do we collectively imagine and create belonging in Canada?

These topics are addressed in our permanent galleries, and a quick tour gives access to many of the key points of intersection. For instance, if we consider again the story of John Knebli, he was travelling to Canada claiming to be a farmer, just at the very close of Canada’s prioritization of agricultural settlement. The small deception, along with the other aspects of his entry to Canada, reflect on the major patterns of entry at the time as well as on some key concerns of immigration authorities. For example, one of the principal concerns among immigration agents and planners in Canada during the period of promoted Western agricultural settlement was that many “desirable” immigrants were in fact artisans or urban labourers who would not stay on the land, but rather would take short-term work for a few years on a farm as a reasonable exchange for the opportunity to move and settle in one of Canada’s emerging cities. Knebli did exactly that when he brought his wife to Canada in 1938: he left farming, moved to a major centre (Toronto) and set up as a skilled craftsman.

The question of integration might be approached through Ellen Burka’s experience. She arrived amid one of the defining waves of immigration following the Second World War: the massive emigrations from the Netherlands. Married to a Czech-born artist she met while surviving the persecutions of the Nazis, her story also opens the question and exploration of the gendering of nationality and citizenship in that period of enormous tumult. Many women inadvertently found themselves either stateless or estranged from their citizenship of birth thanks to citizenship laws that forced them to adopt the national affiliation of their husbands. Out of these origins, Burka arrived in Toronto in the early 1950s – and was soon separated from her husband.

Credit: Azam Chadeganipour for the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21

A single immigrant mother with two young daughters, she needed to find a way to support herself and her children in an unfamiliar country. Coaching skating provided her a living and a means to negotiate the conventions of the time. While any approach to a large issue by way of a personal story runs many risks, Burka’s biography is a unique lens that helps us consider the interplay of powers, authorities, and events, from geopolitics to the intimate and personal. In Perfect Landings, we have the opportunity to consider this story alongside her daughter Petra’s Olympic medal and world championship sash (borrowed for this display from Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame in Calgary, Alberta).

Finally, on the question of belonging and identities, several modern Canadian figure skaters have forged public identities that draw on their roots abroad as well as and their place in Canada. After his early success in Canada, Victor Kraatz was invited to return to Switzerland or Germany to represent those countries as an athlete. He stuck with his choice after immigrating, and continued to represent his new home on the international stage, up to his world championship with ice dance partner Shae-Lynn Bourne in 2003. Second-generation Canadians and well-known skaters Elvis Stojko (parents from Slovenia and Hungary) and Patrick Chan (parents from Hong Kong) have both drawn attention to their own transnational identities. This is sometimes controversial, but modern professional sports occur in a space of remarkable fluidity around national borders. Figure skaters often live in one country, and train and are coached in others. They also travel extensively for competition. These professional migrations may layer on top of personal heritage of immigration, too. In this way, athletes can have a web of connections spanning the globe, which complicates the simple picture of a person competing for their one home country.

In sum, Perfect Landings proposes that immigrants made profound contributions to the development of the sport of figure skating in Canada. By covering personal stories from the 1890s to the early 2000s, and dealing with figure skating history from Nova Scotia to British Columbia, the exhibit represents a good range of content within the history of the sport. These examples also have great value as reflections on some major themes in Canadian immigration history, particularly through the twentieth century.