Credit: Photo by Steven Schwinghamer

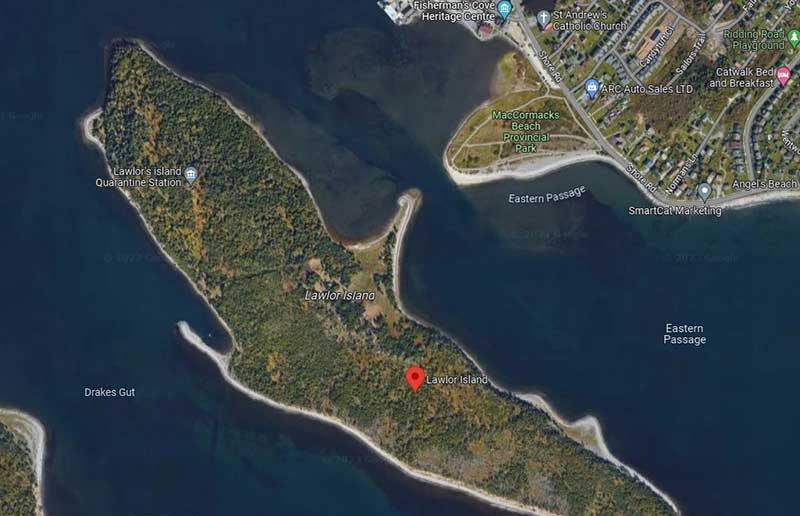

Historians tend to pay close attention when a public site seems “silent” in public memory. This is true of a place quite close to Pier 21 in Halifax Harbour. Lawlor’s Island is next to McNabs Island, close to Eastern Passage. People in Halifax love the harbour islands. We’re all over these things. Devil’s Island, Georges, McNabs – people can’t get enough. But strangely, few people in town know very much about Lawlor’s Island (or its history) at all.

Now this is weird. Why all the love for the other islands, and no joy for this one? Well, Lawlor’s has a complex history. It was the quarantine facility for Halifax in the latter 19th century through to the mid-1930s. It was also a venereal disease hospital during the Second World War. Perhaps a kind of stigma attached to the place based on that history? Or maybe the designation of the island as an environmentally-protected area (and the consequent prohibition on casual visits) has marginalized it in the public mind? If few people go, does the lack of interaction write the site out of public conversation and knowledge? People don’t usually get over to Georges Island, either, but that site occupies a strong place in the public mind – and has been the subject of much historical work, including an energetic restoration and commemoration project by Parks Canada.

I can’t propose a single answer yet as to why we seem to look past this beautiful and historically important island in Halifax Harbour. However, it was a quarantine facility, significant for many immigrant arrivals headed out all across the country, so it’s within our mandate at the Museum to work with that heritage a bit.

We’re lucky in the case of Lawlor’s: Dr. Ian Cameron, a medical doctor and an accomplished historical researcher, has done a great deal of work on the history of the island, including authoring a recent book on the topic. It’s been eighty years since the quarantine facility wound down and a hurricane blew straight through the place in 2003 – but we were hoping a survey of the island would let us tally up what heritage resources survive. See below for more historical background; my next post will discuss what we found!

Credit: Photo by Sara Beanland

Historical Background

Dr. Cameron’s work was a great start for us in understanding the role of the Lawlor’s Island quarantine station. There were a series of public health issues in Halifax during the 1860s after imperfect quarantine procedures led to cholera spreading to a few residents of the city. In the 1870s, the first buildings were set up on Lawlor’s for medical care, and in 1876, a wharf was put in place.

After sporadic use for about twenty years, the island was filled beyond capacity with the arrival of the Doukhobors in 1899. Almost two thousand Russian immigrants had to be accommodated on Lawlor’s, which had a maximum capacity of fourteen hundred patients. The Doukhobors had to pick up the slack in the over-stretched facility, and they did so: they completed a building, did their own cooking and laundry, and so on. However, the size of the group meant they ran out of water on the island after only six days. Despite these and other minor issues, the group fared well medically, and was soon approved to carry on to their new homes in the Canadian West.

(I might mention that the Doukhobor community features in our temporary exhibition, Shaping Canada: Exploring our Cultural Landscapes, presented in 2012.)

Quarantine touched military transit as well, with typhoid outbreaks and the “Spanish flu” leading to quarantines and some loss of life among passengers arriving in Halifax with military transits in the early 1900s.

Lawlor’s Island was never a great location for a quarantine facility. It doesn’t have a source of fresh water, it is sometimes ice-bound in the winter and – of all things – people used to really enjoy picnicking there, regardless of whether people were in quarantine. (More potato salad, Bill? Thanks, Jenny, and I’ll have the cholera too, please!)

These different pressures meant that from 1906 on, health officials in Halifax were looking for another place to house quarantine. It took thirty years, but they finally moved on to Rockhead Hospital in the North End. Over that time, the need for quarantine declined: microscopes and that crazy idea, “germ theory,” brought around serious work in the field of microbiology. Medical science advanced enough that the bacteria or viruses responsible for many of the most serious contagious diseases contained by quarantine were identified. In many cases, vaccines or treatments followed. Quarantine wasn’t needed as much after these advances.