One of the things I love most about working in the Scotiabank Family History Centre (SHFC) at the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 is that every interaction is wildly different. But as diverse as our genealogy research can be, one thing that comes up constantly is the regret that people didn’t ask their family members about their lives and stories when they had the chance.

Too often we take our loved ones for granted, or forget that they had lives before we knew them; that our grandparents were once children with grandparents of their own - who had maybe been born in the 19th century! So when you think about it, while you don’t know someone who was alive in the 19th century, you probably know someone who has firsthand accounts from a person who did; history is much closer than it feels. When I was in high school I had to write a short story about Prohibition and decided to interview my two grandmothers about what it had been like to live in that time. That’s how I discovered that one grandmother used to watch the rum runners and coast guard have gunfights on the Niagara River and the other used to go to Chinese restaurants in Toronto and order “tea” that was suspiciously whiskey-flavoured. Those are incredible stories that, if I hadn’t asked, they might have never thought to tell me. I bet you want to give your grandparents a call now, right?

That’s the most important thing to remember: ask. Your family members might not offer up their stories unprompted because they don’t think anyone is interested, they need their memory jogged or don’t realise how compelling they are. Even when I’m not at work, as soon as I tell someone what I do for a living they immediately launch into their wildest family and personal stories. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been doing research for a family and my questioning gave people the chance to reveal amazing stories to me, stories that the other family members had never heard. All I had to do was ask questions and be interested; I guarantee that every single person has a good story to tell. Think your pie-baking housewife grandmother is boring? Wrong. My grandmother was a pie-baking housewife and in addition to casually watching river-based gunfights once snuck onto someone’s property in the dead of night to rescue an abused dog. Hearing people’s stories is the best part of genealogy and you don’t even have to be a genealogist to do it.

There’s also a practical reason for you to take this advice. Sometimes if a person didn’t take the opportunity to talk to their family and they come to us for genealogical research, it can make it harder for us to help them. Most people know a lot about their immediate predecessors, like their parents and grandparents, but, like me, a lot of people never had the chance to meet their great-grandparents. But in many instances, your parents and grandparents are too young for us to be able to research them - and while it can be very disappointing, grandparents generally like being told that they’re too young for things. Often, if we’re using documents like census records or birth, marriage and death records, more recent ones are not publicly available so we need to be able to research someone who would have been alive in the 1920s and earlier. I don’t blame people for not knowing the names of their great-grandparents, or even their grandparents sometimes, but it can be an obstacle if you’re trying to research your family. The more you know, the more we can help you.

Oral history and genealogical research are distinctly different things, but they are both at their best when used together. Yes, sometimes genealogical research will myth-bust your grandmother’s story that her grandparents met on the ship coming over, but I don’t enjoy disproving someone’s family story and I would never suggest that anyone in your family is a fibber. It was a long time ago! Human memory is imperfect, and it’s natural for stories to evolve over the years. It’s like a multi-generational game of telephone; a few things will inevitably become garbled. But just because oral histories are imperfect (as are many historical documents - they were still created by humans after all), that doesn't mean they’re not meaningful and valuable. Often, those oral histories will inform our research and give us a sense of what to look for and where. A lot of times the records confirm the stories, partially or fully.

Oral histories also function as irreplaceable sources of contextual information. Researchers might be able to find your great-grandfather emigrating from Russia in 1913, but that record can’t tell you why he immigrated or what his personal experience on the ship was like. That’s where oral histories come in! The Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 is a museum of stories precisely for this reason. With just one or the other, you won’t get the full picture. It’s when you use them together that you can get a more complete narrative.

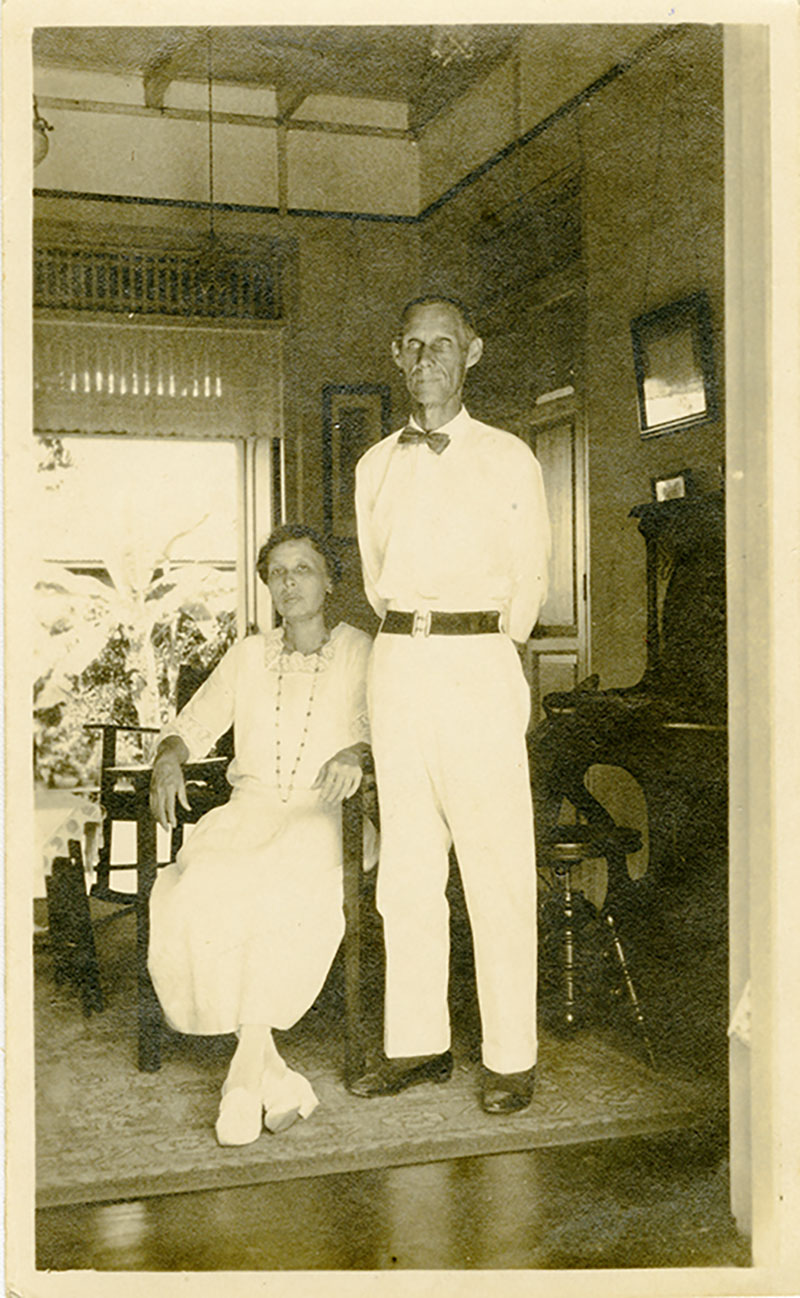

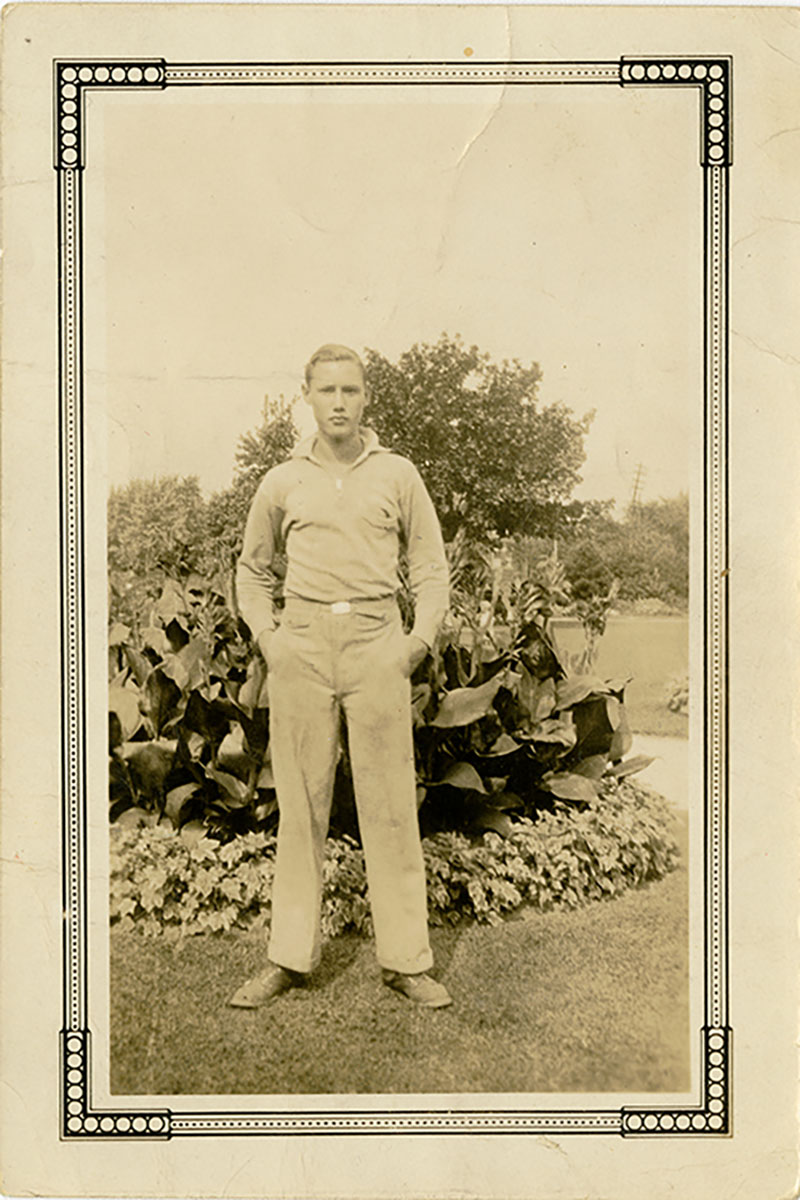

Like everyone at SFHC, as soon as I started working I immediately dove into my own family’s history. My first stop was one of the most outrageous stories: that my great-great-grandmother was a Siamese Princess and a daughter of King Mongkut of King and I fame - and by that I mean the real-life 19th-century King and not Yul Brynner. The story goes that my great-great-grandfather was a Danish sea captain from the island of Heligoland in the North Sea who had a prosperous shipping route to Siam (now Thailand). King Mongkut was so grateful for the wealth the Danish sea captain brought to Siam that he gifted him one of his daughters as a wife who the Captain brought back to Heligoland. I now know that he had 82 children by 32 wives, so it’s maybe a little more plausible than I’d originally thought. His daughter, my great-grandmother Annie (née Edlefsen), was born and lived on Heligoland until the ethnically Danish family fled to Siam after the island came under German control. In Siam, Annie met my Canadian-born great-grandfather Walter Toye (the “e” in Toye comes and goes), a University of Toronto MD, who was working as the royal physician. My grandfather, Cecil Toye, and his four brothers were born in Bangkok and in the 1930s the family immigrated to Niagara-on-the-Lake. I’m guessing that it was not a great time and place to be visibly biracial, as illustrated by one of my great-uncles who started officially using his mother’s maiden name, Edlefsen, after settling there.

(Note: For the sake of transparency I sent this to my parents before posting it and they told me that upon immigrating, Cecil had lived in Toronto and didn’t move to Niagara until after the Second World War. This is exactly when I mean about a game of telephone - I’ve unwittingly been telling this story slightly wrong for years!)

That’s the story as I know it. It was supplemented by the knowledge that Annie’s trunk, the one she’d fled Denmark with, was and remains in the possession of my first cousin once removed who has promised to bequeath it to me - one of the perks of being the family historian. We also have a certificate naming Walter Toye to the Order of the White Elephant, which is still an award given to public officials in Thailand. There are also photos of Walter’s medical office in Bangkok; the juxtaposition of palm trees and old, mildly frightening medical equipment is particularly striking. So those items confirm a number of parts of the story already, and things like that can be a great way to initiate these types of conversations with your family members if you’re not sure how to start. Ask them to tell you the stories behind old photos, or ask about the history, or “provenance”, of family heirlooms.

Now, I know what you’re asking: “Sarah, how many people have to die before you become the Queen of Thailand?” And the answer is: too many to count. Don’t you remember the part about 82 kids? But, if this is true, it would make me fourth cousins once removed with the current King of Thailand, which I did need to use a chart to figure out. So I’ve covered the oral history and the provenance of relevant objects, but does the story hold up with the genealogical research? The answer, as it is most of the time, is partially, yes. I have the immigration document for my grandfather and his brothers in 1931, which confirms their birthplaces as Bangkok. I have lots of instances of Walter travelling between Canada and Siam for medical and missionary work. I assume Annie’s birth record is in Denmark and her marriage record is in Thailand, so I couldn’t use those to confirm the names and ethnicities of her parents. I have managed to find a Danish census record that showed a Siamese woman named Su Fang living in Heligoland in the right time, married to Captain Michael Classen Edlefsen with a daughter Anna who was the right age to be my great-grandmother. I’m confident saying that those details confirm just about everything in the story except the royal connection. But absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, so I’m still working on it.

In summation, I strongly encourage you to talk to the people in your family while you can. I think you’ll be pleasantly surprised by what they have to tell you. If you’re not sure how to start, I would recommend sitting down and going through old photo albums together. And this is the most important part: write the information on the back of the photo. Make sure that the information doesn’t get lost! And, if you can, digitize the photos and documents and save them (with descriptions) for posterity. Then you can post those old photos (or new ones!) on twitter with the hashtag #FamPhoto21 to have your photo included in the digital portrait wall in our new temporary exhibit, Family Bonds & Belonging. In addition to photos, the Museum relies a lot on audio and video recordings of oral interviews. It can be very meaningful to preserve people telling their own stories, and very doable for an amateur genealogist. I have included some resources about how to interview someone below, because it can be hard to know how to prepare and what questions to ask to get the best results.

So go forth and, if you can, call your grandparents!

Oral history resources:

- http://www.library.ucla.edu/destination/center-oral-history-research/resources/conducting-oral-histories-family-members

- https://blog.myheritage.com/2013/06/10-tips-for-interviewing-family-members-2/

- https://www.familytreemagazine.com/premium/20-questions/