by Jan Raska, PhD, Historian

(Updated October 1, 2020)

Introduction

When historians take a historical perspective, they must also remain mindful of the responsibilities they have as scholars to critically analyze, discuss and remember historical events including: crimes, injustices and sacrifices. What obligations are there for historians to recall sensitive and controversial historical events?

Ethical Dimension of Historical Interpretations

Today, we are going to discuss the sixth concept presented in the Historical Thinking Project (www.historicalthinking.ca) — understanding the ethical dimension of historical interpretations.[1] As historians research and write history for a public audience, they must remain vigilant about what kind of historical perspective they are taking — and the ethical dimensions associated. A historian cannot avoid controversial historical events and must understand the difference between what they know to be common ethical ground in contemporary society with what constituted ethics in a bygone era. Therefore, it is vital that historians are careful not to impose their own judgements, using a contemporary lens, on controversial events of the past.

The Chinese Immigration Act of 1885 is a powerful symbol of racial discrimination and exclusion. The Act became law on 20 July 1885. Among its most controversial aspects was the Head Tax of $50 on all Chinese immigrants, further limiting most individuals from entering the country. By 1903, the Chinese Head Tax reached $500. Approximately 81,000 individuals paid the fee to enter Canada. On 1 July 1923, the Canadian government enacted a new Chinese Immigration Act, often referred to as the Chinese Exclusion Act. This new piece of legislation banned all Chinese immigration to Canada except for persons who fit one of three categories: diplomat, foreign student or ministerial permission as a “special circumstance” as listed under Article 9 of the act. For over 24 years, few Chinese were able to enter Canada. Due in part to the participation of Chinese Canadians in the Canadian military, during thee Second World War and a postwar awareness of racism and discrimination in the aftermath of the Holocaust, the federal government repealed the Chinese Immigration Act in 1947.

As a historian, it is quite easy to point out the discriminatory and exclusionary nature of the Chinese Immigration Act in Canadian history. But how do we ethically examine such an event? We make sure to critically situate successive Chinese Immigration Acts in their respective historical periods. These periods demonstrate what Canadian society was like in the 1880s and 1920s—one in which Chinese Canadians were viewed as racially inferior in the broader Canadian community, which also feared foreigners and their labour.

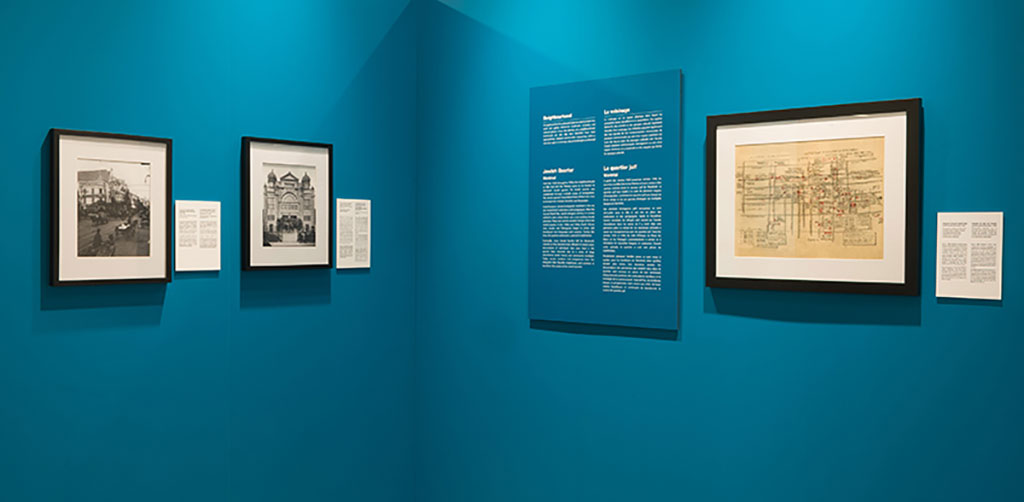

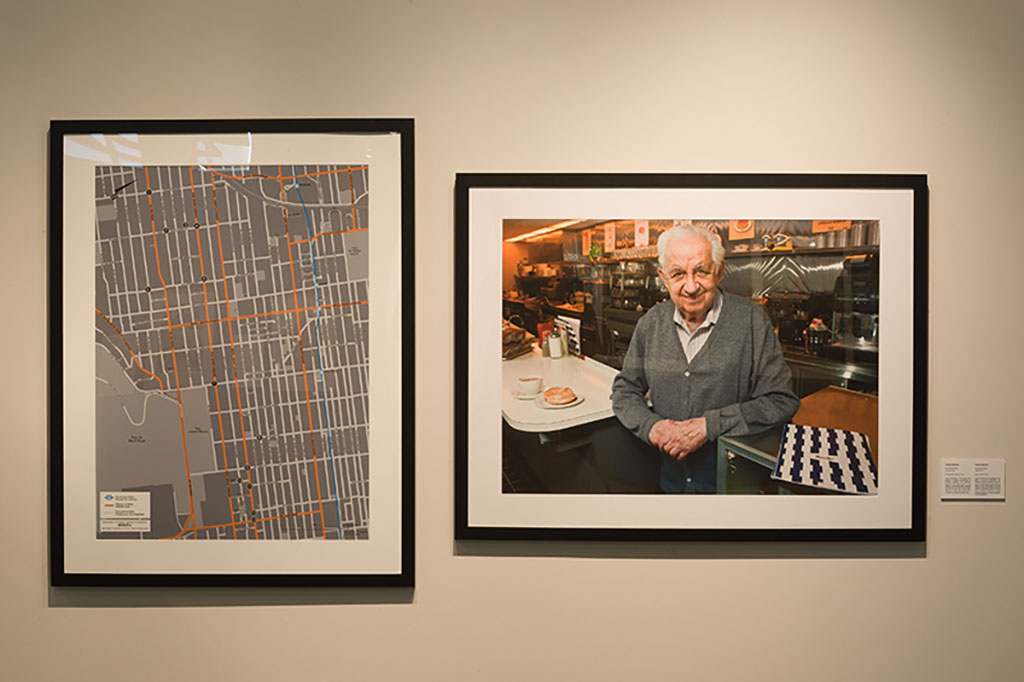

As historians and citizens, we need to treat past events ethically. An example of this is Montreal’s old Jewish quarter which served as a case study in our 2012 temporary exhibit Shaping Canada: Exploring Our Cultural Landscapes. In researching this case study, the historian must remain aware of past events and their impact on the community under study. In this case, we were mindful of the effects of antisemitism in Quebec prior to the Second World War and the Holocaust. During this period, existing scholarship noted that Quebec was a conservative and Catholic province whereby ethnic minorities were often marginalized and subjected to discrimination. The type of discrimination that ethnic and religious minorities experienced daily on a personal level at the hands of the majority French Canadian population is not only indicative of the existence of discrimination, but also illustrates the social environment in Quebec before, during and after the Second World War. After 1945, thousands of Jewish refugees fled war-torn Europe and were admitted to Canada. With the assistance of the Jewish Immigrant Aid Society, Jewish refugees found accommodations and employment and acquired basic necessities, such as clothing. Throughout this period, members of the Jewish community continued to be marginalized by antisemitism.

Conclusion

Historians should remain cognizant of using a contemporary lens to judge events, people and societies in the past. When discussing past historical events, historians oftentimes do not remain neutral. Good historical scholarship does not ignore or attempt to whitewash discrimination, crimes or events of the past, but treats them ethically by contextualizing them within the period they took place. As a result, historians avoid making ethical judgements about the past until they have examined and contextualized the surrounding historical period.

Some images of the Neighbourhood section of Shaping Canada, featuring Naomi Harris’ contemporary portrait photography.

- Historical Thinking Project, “Concepts,” accessed: 20 November 2012, http://historicalthinking.ca/historical-thinking-concepts.