by Jan Raska, PhD, Historian

(Updated October 1, 2020)

Introduction

History is often seen by the public as the study of dates, names, places and events. As a discipline, history is much more diverse and multilayered than many individuals realize. The discipline of history can be viewed as a complex interplay between continuity and change.

Identifying Continuity and Change during Research to Support Exhibit Development

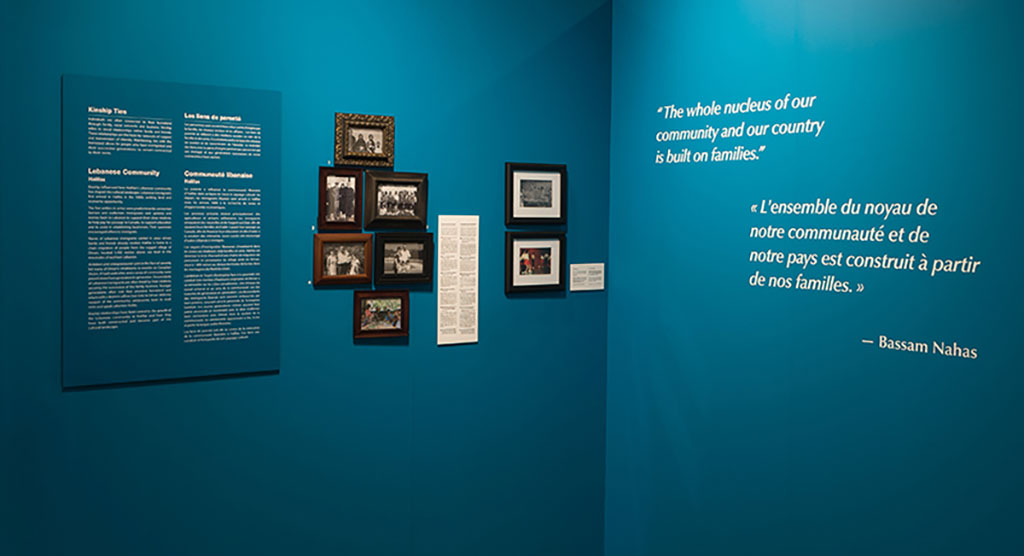

Today, we are going to discuss the third concept presented in the Historical Thinking Project (www.historicalthinking.ca)— identifying continuity and change.[1] In researching a particular project, historians do not simply note when continuity or change occurred, but rather they investigate further to find whether continuity happens when change is abundant or if change occurs when continuity is present. In our 2012 temporary exhibition, Shaping Canada: Exploring Our Cultural Landscapes, the case study of the Lebanese community in Halifax, Nova Scotia provides us with a unique example of the interplay between continuity and change.

In researching Lebanese immigration to Canada, and in particular Halifax, previously published scholarly literature and archival records discussed the role of emigration. These works often portray a painful journey of leaving the homeland for Canada’s shores. Existing research also discussed how these immigrants maintained agency in their new lives as they transplanted their families and their experiences to a new country. In conducting research for Shaping Canada, I found that many of the earliest immigrants to Halifax were from the village of Diman located 1,400 metres above sea level in the mountains of northern Lebanon.

Over several generations, a chain migration network took root. Relatives of those Lebanese who came earlier were now sending home information about life in Canada and even financially assisting their kin in coming to Canada. In many instances, early Lebanese immigrants, who arrived in Halifax, often sent funds back to the old country to pay for their relatives’ passage to Canada and also supported them in commencing school and starting a business. Where previous research indicated uprootedness, resettlement, struggle, ambition and success as examples of change, I also found continuity which indicated human agency. Lebanese immigrants maintained ties to their old country and also re-established or rather transplanted their identities to Halifax. Over time, many Lebanese families were reconstructed and lived in the same areas of the city as did other Lebanese families. They opened their own businesses, such as convenience stores, and hired close relatives to work for them.

The lives of Lebanese immigrants in Halifax illustrated that they were agents of their own destiny. Ambition and entrepreneurial spirit in the face of poverty led many of Diman’s inhabitants to resettle on Canadian shores. A hard work ethic and a sense of community were passed down from generation to generation. Descendants of those same immigrants were often hired by their relatives securing the succession of the family business. Successive generations continue to visit their ancestral homeland and return desiring to emphasize their historical links to Diman.

Conclusion

In the case of Lebanese Canadians from Diman, their resettlement to Canada’s shores did represent a change in their personal histories, but also served as an example of continuity. Kinship links permitted immigrants to preserve their language and identity after resettlement and maintain ties with their families in Canada and Lebanon.

Some images of the Kinship Ties section of Shaping Canada, featuring Naomi Harris’ contemporary portrait photography.

- Historical Thinking Project, “Concepts,” accessed: 20 November 2012, http://historicalthinking.ca/historical-thinking-concepts.