by Jan Raska, PhD, Historian

(Updated October 20, 2020)

Introduction

For centuries, child orphans have sought permanent resettlement in Canada. Refugee orphans seeking to enter Canada today must hold legal documentation and provide testimony to a federal immigration official that he or she is a minor. Otherwise, within Canadian immigration policy, they are treated as adult refugees. Accompanied by a lawyer, social worker, or trusted community member, refugee orphans must be interviewed by an official from the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada.[1]

Canadians are less aware of the past immigration of refugees and orphans to Canada. Many Canadians have heard of the ‘Home Children’ – over 100,000 adolescent migrants from orphanages and working-class backgrounds in Britain who were resettled in Canada, between 1869 and 1932. But little has been written about another, much smaller, experiment nearly a century ago that brought Armenian child orphans from Ottoman Turkey to Canada. Increased public awareness of the Armenian genocide, between 1915 and 1923, coupled with lobbying on the part of prominent Canadians, pressured federal immigration officials to admit 109 orphaned boys on an “experimental basis.”[2]

Armenians as “Asiatics” and Canadian Immigration Policy

Prior to the Canadian government’s decision to admit a small group of Armenian child orphans beginning in 1923, federal immigration policy prevented immigrants from the Middle East or Caucasus regions to enter the country. The 1910 Immigration Act gave the federal Cabinet discretionary powers to further control the movement of immigrants into Canada. Section 38 of the Immigration Act prohibited the entry of individuals “…belonging to any race deemed unsuited to the climate or requirements of Canada.”[3] In addition to “climatic unsuitability,” an Order-in-Council passed in March 1910 imposed a $200 head tax on immigrants of “Asiatic” origin. At the time, the federal government considered Armenians to be Asiatics.[4] As a result, Canada’s gates were virtually closed to Armenian immigration.

In 1922, the League of Nations, a predecessor to the United Nations, established the Nansen Passport, which provided stateless refugees with an internationally recognized travel document. Named after the League’s first High Commissioner for Refugees, Fridtjof Nansen, the passport served as a travel certificate establishing a refugee’s identity, and was destined for use by over 1.5 million displaced by the First World War and the Russian Revolution. Although recognized by more than 50 countries, Ottawa initially hesitated to legitimize the certificate out of a fear that it was a “one-way document.”[5] The Canadian government held on to its sovereign right to deport individuals it deemed as inadmissible and/or ‘undesirable.’ As many Armenian child orphans were stateless and therefore eligible to receive the Nansen Passport, their entry into Canada remained prohibited under existing immigration legislation.[6] In 1923, federal officials passed Order-in-Council P.C. 1923-182 (31 January 1923) further preventing "any immigrant of “Asiatic race" from entering the country.[7]

With such a stringent immigration policy in place, the Canadian press, voluntary aid organizations, and immigrant groups continued to pressure the federal government to help resettle survivors of the Armenian genocide. Two patrons of the Armenian Relief Fund in Canada, Sir Henry Pellatt, a Canadian soldier and financier, and the Governor-General, His Excellency, Lord Julian Byng, were prominent individuals who lobbied federal officials on behalf of the organization.[8]

With the Canadian press continuing to publish articles on the plight of the Armenians, public pressure soon forced the Canadian government to act. By creating an exemption to the order-in-council, federal immigration officials implemented a special scheme later labeled as “Canada’s Noble Experiment,” whereby 109 boys and 39 girls were brought to the country between 1923 and 1927.[9]

Armenian Relief Association of Canada (ARAC)

On 4 April 1923, the Department of Immigration and Colonization informed Dr. A.J. Vining, general secretary of the Armenian Relief Association of Canada (ARAC), that the organization would be permitted to bring Armenian child orphans to Canada subject to seven conditions:

- ARAC was responsible for the children until they reached the age of eighteen;

- Selected children for resettlement had to be “sound and healthy, without palpable predisposition to disease. No disablement of limb or mental defectiveness”;

- ARAC was to secure a suitable distributing home for the children prior to their departure to foster homes;

- Regular supervision of each child was to be maintained by ARAC with proper documentation for each visit;

- Compliance with all provincial laws pertaining to the education of the children;

- Each child was to be placed in a foster home with a parent legally responsible for their custody;

- The children would remain under the jurisdiction of the office of the Supervisor of Juvenile Immigration and be visited by officials from the Department of Immigration and Colonization[10]

The ARAC was an interethnic and interdenominational public organization, established a year earlier, with a predominantly Protestant affiliation. The organization was responsible for educating the adolescent refugees, training them in agricultural techniques, and providing them with assistance in adjusting to Canadian society. The organization was later joined by the United Church of Canada in sponsoring Armenian adolescent women for eventual work as domestics in southern Ontario.[11]

The Georgetown Boys and Girls

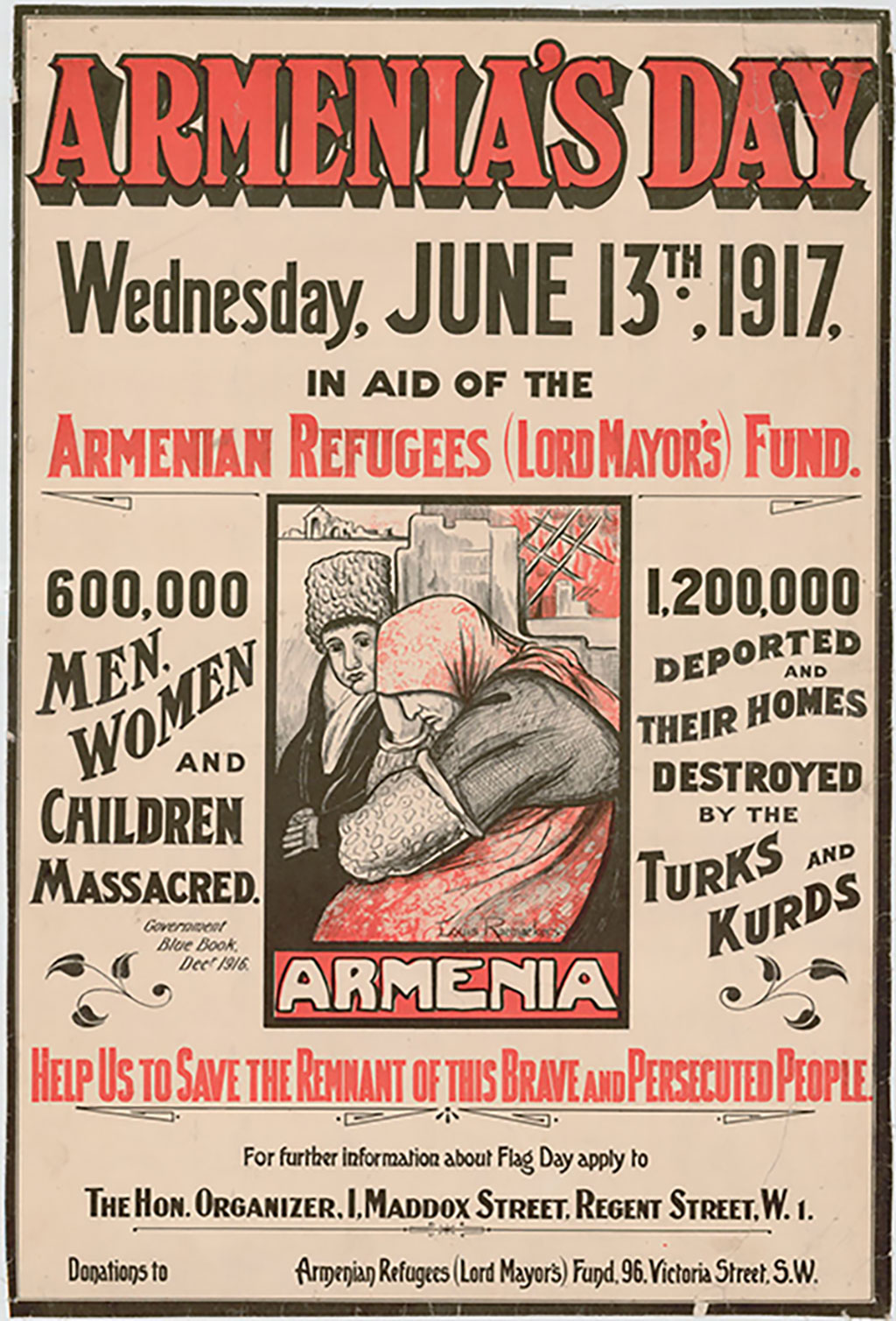

Beginning in May 1923, the Canadian government informed its High Commissioner to the United Kingdom, Hon. Peter Charles Larkin, that the Department of Immigration and Colonization would admit Armenian child refugees on the condition that they pass their medical inspection. Canadian diplomats in London were to inform the Armenian Refugees (Lord Mayor’s) Fund – an umbrella relief organization – of the resettlement plan. Although initially reluctant to resettle Armenian refugees in Canada, the federal government later granted $25,000 to the resettlement scheme.[12]

An initial group of 50 boys left from an orphanage in Corfu, Greece, and sailed by ship to Marseille, France, before boarding SS Minnedosa for its transatlantic journey from Cherbourg to Quebec City. The first group of boy orphans arrived on 29 June 1923. Ranging in age from eight to fourteen, the boys were later resettled at the Cedarvale Farm in Georgetown, Ontario, which became the site of the Armenian Boys’ Farm Home. The home was under the auspices of ARAC’s Farm and Home Committee. Once there, the Armenian children were educated in Canadian agricultural practices. A second group of Armenian orphans from Corfu sailed aboard SS Brage, arriving at Pier 2 in Halifax on 30 September 1924. These two waves brought over 90 Armenian boys and were eventually followed by a third group of 29 boys. In 1927, a group of 39 orphaned girls were resettled in Canada and brought to the Georgetown farm home.[13]

Canadianization of Armenian Orphans

An interesting aspect of the resettlement of Armenian child orphans to Canada is the attempt by ARAC staff to rapidly integrate the youngsters upon their arrival. Unbeknownst to the children, Dr. A.J. Vining, who was responsible for the idea of resettling the Armenian orphans in Canada, had contacted federal immigration officials approximately six months prior to their arrival to suggest that in the spirit of Christian idealism, “we propose to drop the Armenian names of these children when they arrive here and give them Canadian names…” In an attempt to hasten the integration and “instant Canadianization” of the youngsters, Vining created a list of Canadianized names to help them avoid “…any difficulty they may have in holding property when they reach their majority” due to their foreign-sounding names.[14]

From their arrival at the home, the boys detested their new Canadian names. Having lost their parents, siblings, and homeland, many of the orphans sought to hold onto their Armenian names as an important piece of their ethnocultural heritage. In early 1925, Rev. I.W. Pierce, who replaced Vining as general secretary of ARAC, visited Georgetown upon hearing of the boys’ vehement opposition to their new names. Pierce later wrote to Acting Deputy Minister F.C. Blair in the Department of Immigration and Colonization, to suggest that the Farm and Home Committee had disapproved of Vining’s initiative and noted that during his presence on the farm, the orphans resented their new names. As a result, the boys’ use of their Canadianized names simply lapsed.[15]

A visually striking example of the ‘Canadianization’ of the Armenian boys’ names can be found in an ARAC document listing the first contingent of 50 boys. Sarkiss Tapandjian, age 12, became Peter Tapandjian Robinson, while Hagop Abrahamian, age 9, became James Abrahamian Gourlay. In most other cases, the boys’ first names were phonetically similar to their new Canadian names, for example, Tavit became David. All the boys’ family names were used for middle names.[16] By 1928, the orphans acquired the necessary farming skills and were placed with farm families across southern Ontario.[17] Most of the Georgetown boys actively maintained their Armenian names and heritage throughout their lives in Canada.

Conclusion

In the early 1920s, ARAC lobbied the Canadian government to resettle over 2,000 refugee children. With Armenian immigration prohibited under existing Canadian immigration policy, federal officials refused to permit entry. Public pressure on the part of Canadian press outlets, voluntary aid organizations, immigrant groups, and prominent Canadians, including the Governor General, prompted federal immigration officials to permit a small group of Armenian orphans to enter Canada. The resettlement of Armenian refugee children is significant in Canadian immigration history. The scheme represents the Canadian government’s initial involvement in international humanitarian aid by providing assistance to non-British and non-Commonwealth refugees.[18]

The 148 Armenian child orphans, who were resettled in Canada as part of “Canada’s Noble Experiment” survived the genocide of their ethnocultural community. In many instances, the children brought to Canada as part of a concerted public-private effort to help Armenian survivors began new lives elsewhere, remembered very little of the First World War and its aftermath. A child of Armenian genocide survivors, historian Isabel Kaprielian-Churchill notes that the Armenian children retained “only tiny glimpses” of memory including a family member’s embrace, the taste of their mother’s cooking, sounds of constant wartime shelling or stress from the disappearance of a loved one.[19] With little or no memory of their family’s history, it is not surprising that many of the orphans at the Georgetown Farm Home wanted to preserve any attachment or links to a familial past and a shared Armenian ethnocultural heritage.

In all, the Armenian children brought to Canada received an education in agriculture, and Canadian customs and traditions. Upon leaving the Georgetown Farm School, many of the boys and girls joined existing Armenian communities across the country and continued to reshape their lives in Canada.

Credit: Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1983-28-291

Credit: Canada. Immigration Branch / Library and Archives Canada / PA-147570

- Fram Dinshaw, « Immigration Minister Explains Why Canada Can’t Accept Syrian Orphans » National Observer, 24 December 2015, http://www.nationalobserver.com/2015/12/24/immigration-minister-explains-why-canada-cant-accept-syrian-orphans.

- Jack Apramian, The Georgetown Boys (Zoryan Institute of Canada, 2009), 73-77; Armenian Genocide Centennial Committee of Canada (hereafter AGCCC), “Georgetown Boys,” http://genocidecentennial.ca/armenian-genocide. Apramian’s monograph was posthumously edited and revised by Lorne Shirinian who also wrote an introduction. In April 2004, the House of Commons passed a resolution (Motion 380) acknowledging the Armenian Genocide of 1915 and condemning this act as a crime against humanity. See “Canadian Parliament recognizes Armenian genocide,” CBC News, 25 April 2004, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/canadian-parliament-recognizes-armenian-genocide-1.509866.

- Library and Archives Canada, Statutes of Canada. An Act Respecting Immigration, 1910 (Ottawa: SC 9-10 Edward VII, Chapter 27). See page 14.

- Apramian, xvii.

- Apramian, xxxv.

- Apramian, xxxv-xxxvi.

- Library and Archives Canada, Privy Council fonds, RG 2, vol. 1322, item number 400139. This regulation excluded agriculturalists, farm labourers, female domestic servants, and “the wife and child under 18 years of age of any person legally admitted to and resident in Canada, who is in a position to receive and care for his dependents.”

- Apramian, xxxv-xxxvi.

- Apramian, xvii; Isabel Kaprielian-Churchill, Like Our Mountains: A History of Armenians in Canada (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2005), 161-163.

- Apramian, 25-26; AGCCC, "Georgetown Boys."

- Isabel Kaprielian-Churchill, "Armenians" in Encyclopedia of Canada’s Peoples, ed. Paul Robert Magocsi, 215-231 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999), 218.

- Apramian, 25-26.

- Apramian, xxxvi, 73-77; AGCCC, "Georgetown Boys."

- Apramian, 73-77; AGCCC, "Canada and the Armenian Genocide", http://genocidecentennial.ca/canada-and-the-armenian-genocide.

- Apramian, 73-77; AGCCC, "Georgetown Boys."

- Apramian, 73-77.

- AGCCC, "Georgetown Boys."

- Ontario Heritage Trust, "Armenian Boys’ Farm Home, Georgetown" 5. See https://www.heritagetrust.on.ca/plaques/armenian-boys-farm-home-georgetown.

- Kaprielian-Churchill, Like Our Mountains, 200-204.