by Jan Raska, PhD, Historian

(Updated October 26, 2020)

Introduction

V-E (Victory in Europe) Day, May 8, 1945, marked not only the beginning of the return home from Europe for Canadian military personnel, but also a new period in immigration to Canada. During the war, immigration had slowed almost to a standstill. The postwar situation completely upended this inactivity. People from all over Europe began to arrive, and Pier 21 became the busiest ocean port of entry in the country. The circumstances of these newcomers varied greatly. Some were war brides seeking to rejoin their Canadian soldier husbands, some were displaced persons and political refugees who had undergone the destruction of their homes, environment, and security, and some were simply seeking greater opportunity.

War Brides

Even before the end of the war, women known as the war brides, who had married Canadian soldiers posted overseas, began to arrive in Canada. Almost all of the approximately 44,000 women and their 21,000 children were British, with the others of diverse European backgrounds. Almost all of them landed at Pier 21.

“...My last papers were checked and Orwell, who could wait no longer, came leaping over the barriers to sweep me up in the most wonderful hug there ever was. My hat flew off; I dropped my purse, which promptly spilled its contents over all the floor…” — Myra D. Ennis, arrived from Scotland, 1946.[1]

Credit: Photograph of Ethel Violet and William Keogh, February 1942, Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (ZDI2016.156.1)

Displaced Persons and Refugees

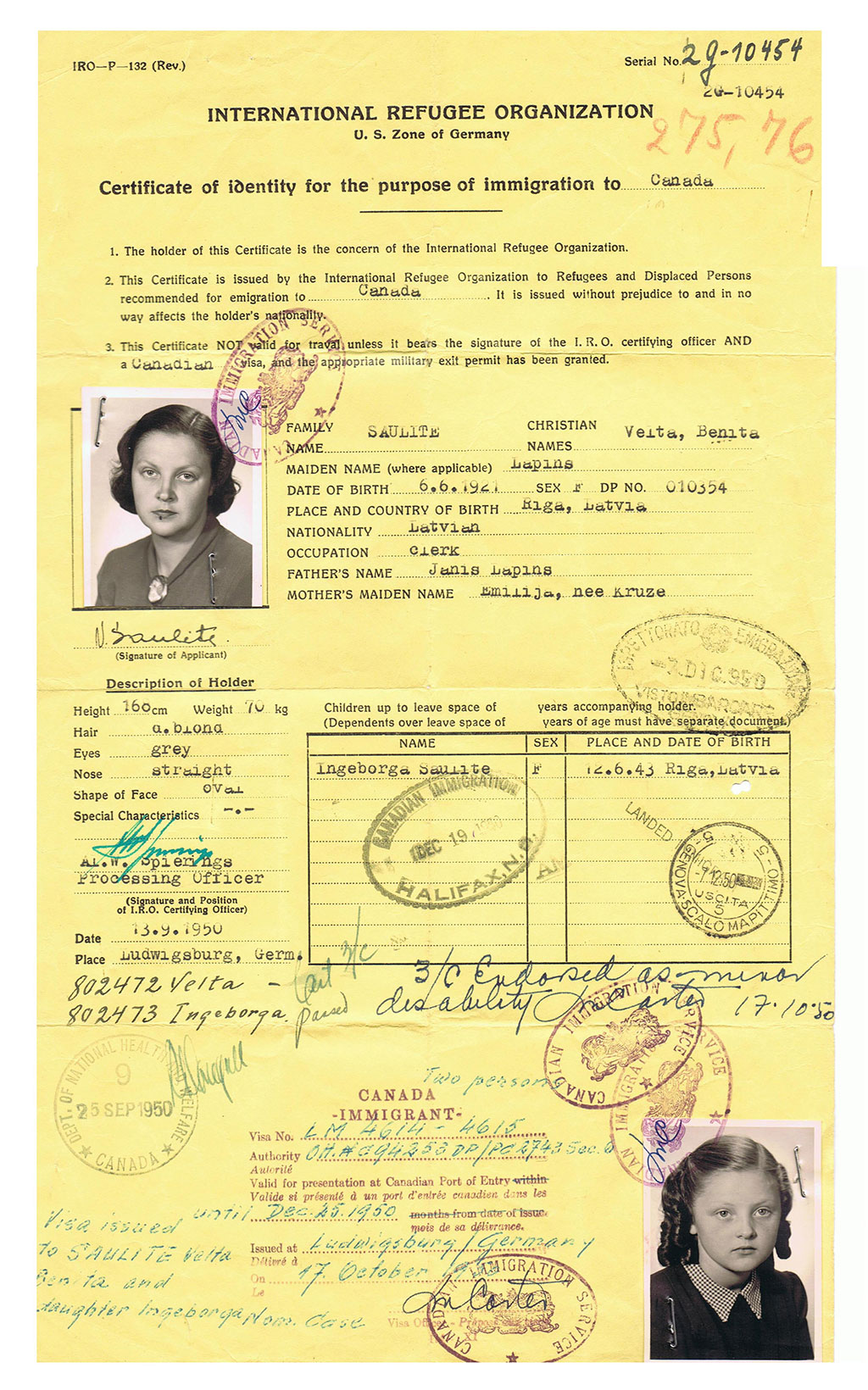

In 1947 Canada began accepting displaced persons and political refugees from war-torn Europe. Until 1952, almost 200,000 people were admitted under the Displaced Persons (DP) Movement. The economic boom in Canada created a labour shortage, so many of them were admitted as labourers. Others were sponsored, but some were admitted even without secured sponsorship, travel documentation, or personal identification. A majority of the Displaced Persons who arrived through Pier 21 were from France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy, Austria and Germany. Most of the political refugees fled from former Czechoslovakia, Soviet Union, and Yugoslavia, as well as Poland and Hungary.

“They came with almost no items of value; their few belongings were carried in sacks of various kinds and a few battered cardboard suitcases, these people came from many walks in life; farming, industrial trades, merchandising and, in many cases, professional fields. The ravages of war had taken away their homes, their livelihood and, in too many instances, their loved ones.” — Arthur J. Vaughan, Customs Officer at Pier 21, 1945 to 1965.[2]

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (DI2014.460.5)

Postwar European Immigrants

Many immigrants to Canada in the postwar period came simply to seek better opportunities. They came from all over Europe, the majority from the United Kingdom, Italy, West Germany, the Netherlands and Poland. They settled all across the country in both urban and rural areas. Largely due to the postwar boom, these newcomers found work in industries such as agriculture, manufacturing, and construction.

“...In 1952 my father received a letter from a friend from his hometown, Steenwijk, the Netherlands… He extolled the virtues of living in Canada, a land of opportunity for those who were ambitious and worked hard. My father was convinced that Canada was for him but my mother was not so sure...” — Albert deVos, arrived from the Netherlands, 1953.[3]

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (DI2013.1529.2)

Conclusion

Pier 21 witnessed three large movements of immigrants after the Second World War. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, 44,000 War Brides and their 22,000 children arrived in Canada. At Pier 21, these war brides and their children disembarked from their ships and were met by voluntary service agencies that cared for their needs, and arranged their train travel to their new homes across Canada. From 1945 to 1971, nearly a million postwar immigrants passed through Pier 21. More than a fifth of these newcomers were European displaced persons and political refugees fleeing the aftermath of war and/or repressive postwar regimes. Canada admitted these individuals who qualified as farm labourers and industrial workers. They arrived at Pier 21 with diverse sociopolitical backgrounds and ethnic identities. With little or no money, clothing, and documentation, they often required the assistance of social agencies before reaching their new homes.