By Steven Schwinghamer, Historian

Like Canada, soccer is beautiful…anyone can do anything. There are no restrictions, and if there are restrictions, they can be challenged, like in a soccer match. Like Canada, soccer can make you equal. If there are others on your team that are stronger than you, they will support you, they will help you. Canadian society is like this too.[1]

Joe Pereira, Portuguese Canadian

Introduction

Sport has long been a tool for culture production and exchange; now, many people use it formally and informally as a device for migrant expression and contribution, as well as adaptation and integration. Sociologist Ramón Spaaij argues that “[s]port serves as a significant site for civic participation, potentially enabling resettled refugees to foster social relationships with, and cultural knowledge of, the host community.”[2] The global nature of football, or soccer, means that many people arrive with skills and knowledge of the game. In Canada, that previous experience is a useful foundation for adaptation after arrival. Participating in soccer aids adaptation for migrants in Canada.

The sport benefits those who play, volunteer, administer, officiate, coach, and cheer for teams across the country. Part of recognizing the value of soccer, though, is to understand that the stories that can be produced around sport can be instrumentalized in ways that can erase or obscure certain aspects of migrant experience to serve other goals; and that the stories and identities produced through soccer are often multiple and not just national. Tracing player experiences, adaptations off the field, and some of the complexity of identities around sport shows that migrants build communities and make their homes in Canada through soccer.

On the Field

Sport can be a potent tool to promote the adaptation and inclusion of marginalized people, including immigrants and refugees. One refugee youth interviewed by sociologist Greg Yerashotis recalled this affecting his life well before arrival in Canada:

When I was little we moved around a lot. In Afghanistan, because of war we got kicked out from [there] so we went from Afghanistan to Tajikistan, from Tajikistan to Kazakhstan. But the one thing I loved, and I looked for in all these different places was football. That’s how I kind of connected with people from these new places.[3]

The long familiarity with the game, built from playing all over the world, is reflected in Alan Efetha’s memories of growing up in Kenya:

We were supposed to be taking care of the cows, but once in a while, we’d forget and we’d get playing. And the cows would eat grass in the pasture—it was a community pasture—and we were so much involved in playing that the cows would take off and head back home when the evening came. By the time we realized the cows had gone home, they were already at home. They knew where to go. Yeah. So, we took care of the cows and we played when we were young. And then we also played soccer a lot—football, we call it.[4]

Efetha brought his love of football to Saskatchewan, where as his studies progressed after his immigration, soccer was a significant part of his social life, including through the African student association at the University of Saskatchewan. His student association joined with the Central & South American student group to play football together—again, something they had in common from before and after migrating to Canada—and this gave the groups a chance to make broader social ties.

Credit: CMI (DI2019.66.1).

Soccer can help people build community, in part, through the feelings and relationships of players on the field. The empowerment and exhilaration of sport matter greatly to immigrant athletes, especially where they might otherwise feel lonely and marginalized. The sport can afford a chance to challenge cultural frontiers with their participation, too. A young woman interviewed by Yerashotis remarked,

I liked things that made me feel strong, I liked Taekwondo and soccer. I liked things where I could be a little bit physical and not get in trouble…in society women especially have to look a certain way and act a way, when you play a sport, it doesn’t matter how you look if you don’t have the skills…the Hijab wasn't relevant at that point. I never felt, when I was in the zone playing sport, like I was different — I felt attached to my body and my skin.[5]

Overcoming difference appears, too, in the words of a Portuguese immigrant interviewed by anthropologist Marcelo Herrera:

In soccer we found a way to recreate a bit of home here in London. Through our pick-up games we finally began to integrate with our community because we felt relaxed enough. Though some of us had been here for years, none of us felt we had integrated with anyone…Soccer became [our] way to relax, to forget about many anxieties and inadequacies in this country. Soccer was something we could do without good English or knowing Canadian culture and customs. This helps a person […] in their heads and in their hearts.[6]

Overcoming difference on the field can run into eliding or collapsing important distinctions, though. In the case of star players, there is a risk of storytelling that overwrites the individual athlete in creating or promulgating an instrumental and ideal representation of migrant experiences. In contemporary Canadian soccer, this is notable in the case of Alphonso Davies, whose trajectory from refugee camp to international soccer star presents him “comme incarnation de « l’immigrant idéal » (McLaren et Dyck 2004) et sa constitution comme figure de « la diversité » au Canada.”[7] Bachir Sirois-Moumni and Jean-Charles St-Louis trace this production of Davies’ experiences, including the obscuring of any complications for the family after arrival in Canada.[8] This signals some necessary caution for representation of case studies and stars, to avoid losing their historical particularity in the service of alignment with useful myth.

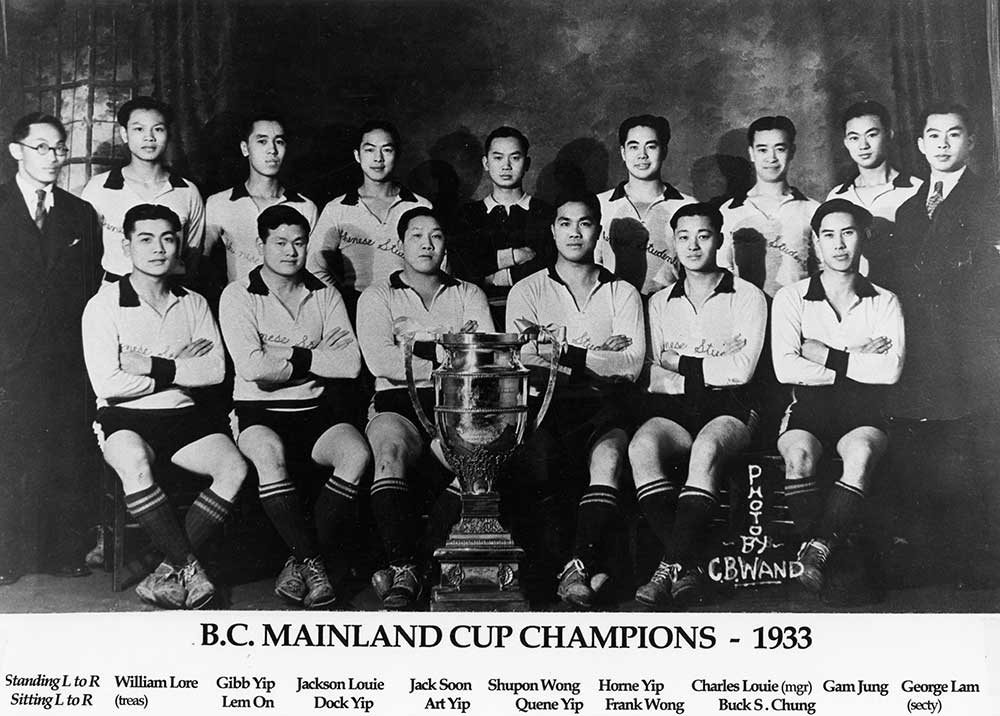

A striking example of migrant community adaptation and empowerment through sport may be found in the soccer history of British Columbia. The Chinese Students football team was formed in 1919, in Vancouver, British Columbia, and they became a celebrated soccer team in the Lower Mainland.[9] They played in a league against white teams at a time when discrimination against Chinese Canadians was pervasive and acceptable in almost every facet of Canadian life. Chinese Canadians were excluded from voting and, lacking this power, were readily targeted by federal, provincial, and municipal laws and bylaws meant to block their entry and prevent their participation in Canadian society.

Credit: BC Sports Hall of Fame.

In this context, the storied Chinese Students—called this because when they formed many of the players were still in secondary school—represented their community, which adopted and enjoyed their success. In particular, the 1933 team’s victory in the Mainland Cup triggered a holiday and enthusiastic festivities in Vancouver’s downtown East Side, then home to many Asian immigrants.[10] The son of one of the team’s stars remembers their impact, saying,

He was born here, but my father had none of the rights of other Canadians. Soccer was one of the only opportunities he had to compete as an equal…Those players won more than a trophy. They broke down barriers, they won respect for their community and they left a legacy that continues to this day.[11]

In the Stands and Minivans

As we see with the Chinese Students, the inclusive influence of soccer extends well away from the pitch and the players. Spectators, sponsors, officials, and others all participate in identities forged through football. As argued by historian Stephen Fielding, “[s]ports clubs were among the first entities created by newcomers, who hinged many of their aspirations for community, recognition, and inclusion on the backs of the athletes who represented them…Such teams formed the heart of a vibrant soccer scene on the social margins of postwar Toronto.”[12] Further, as Hugo Santos-Gomez notes in his work on immigrant soccer in California, “soccer players are compelled to become civic and politically engaged in order to make possible the minimum conditions required to play, i.e., access to public spaces amenable to practice the sport.”[13]

Immigrant engagement to establish and grow the sport is reflected in the earliest development of soccer in Canada. David Forsyth, known as the “father” of Canadian soccer, was a Scottish immigrant. He arrived as a baby from Scotland in 1853. Forsyth had a notable career as a player in early international and university games but also worked to expand the sport in Canada. He founded the Western Football Association, a league of 19 teams in Southern Ontario, in 1880, and he coached many future soccer stars through his work as a teacher in a Berlin (now Kitchener) / Waterloo, Ontario area high school through the late 1800s and early 1900s.[14]

This sport leadership work continues to the present, and at every level of the game. At the grassroots level, Kenyan immigrant Alan Efetha had played football as a child in Africa and continued with the game at the University of Saskatchewan after coming to Canada in 1984. When Efetha moved to Lethbridge, he took up coaching. He links coaching to his value of service, noting “Lethbridge is too big to be a volunteer fireman, so I made a choice of—because I’m all, like, don’t move around like I used to move around, but I have a passion for football soccer. I started coaching. So I coach soccer for the Lethbridge Soccer Association.”[15] Efetha notes the challenge of coaching with his sons also active in the sport, but he is evidently proud of sharing the sport in his family: “I’m coaching my seven-year-old, but he’s playing with older boys. He’s a big boy. He wanted to be challenged. He wanted to play with ten-year-olds. So he’s playing with ten-year-olds. And he seems to be doing pretty good.”[16]

In team and league offices across Canada, immigrants—and notably women volunteers—can gain administrative working experience and a social and professional network to support their move into both Canadian identities and possibly paid Canadian employment.[17] With this in mind, we see the framework for Herrera’s assertion that a league like the Muslim Youth Soccer League, with its core of volunteer women leaders, “is not meant to ideologically separate Muslim women from other Canadians but to integrate them to Canadian society” as they reproduce Canadian norms.[18]

This integration extends beyond the ways migrants produced identity to casual and social networking. Immigrant soccer parents, for instance, recalled in interviews that “they made their first Canadian friends through their involvement with their daughter’s or son’s soccer.”[19] The social, off-the-pitch importance of soccer was reflected in a study of soccer and integration in Germany, which found that their participant soccer players reported visiting resident Germans in their homes.[20] A practical but important example of the engagement soccer fosters can be found among immigrant parents with children in the sport, who are pushed along in getting a driver’s license to help with team transportation.[21] In sum, the benefits for the communities and the parents can be profound. As Sonia Pereira tells Herrera,

At the fields I met other Portuguese immigrants, and immigrants from other countries. We shared stories about our lives back home and our new lives here – made me feel heard and seen as something other than a mother and wife. I felt part of a larger community of immigrants, and of the bigger general community. I felt real. There is such a thing, you know, as being real but still feel invisible.[22]

The use of soccer for reinforcement of cultural ties works in complex ways. Parents of second-generation immigrant children in Canada turned international soccer trips into occasions for their children to forge or recover links to their ancestral homelands. Fielding observes that “[b]y travelling to the ancestral homeland, they transformed youth sport from what had been an ordinary local practice into an event of transnational significance.”[23] These trips, often organized by community leaders who were invested in the diasporic consciousness of their youth, also complemented state policy and community transnational networks.[24] Fielding quotes an interview with Italian immigrant Michael di Biase, who says “We called it ritorno ai radicci” (returning to our roots). Di Biase is himself an example of an immigrant who took up leadership in Canada both within the soccer community and in politics: he was president of the Woodbridge Strikers Soccer Club and mayor of Vaughan.[25]

Multiple Identities

These trips reflect the kind of double consciousness we often mark in migrant and diasporic communities. Every World Cup is a spectacle of competing fandoms in Canada thanks in part to this polyvalence. In 2014, CBC’s David Common remarked that it is “no surprise in a country built on immigration you can find supporters here of all 32 teams.”[26] This public expression of fandom for other countries follows a turning point in Canadian sport multiculturalism. Following the World Cup victory of Italy over West Germany on 11 July 1982, a quarter of a million Italian Canadians erupted onto the streets of Toronto (especially around St. Clair West) for a tremendous street party. Historian Stephen Fielding argues that “The 1982 World Cup Street Party gave Italian Toronto an ‘identity-giving past,’ around which it built a collective memory to explain their story of settlement, struggle, and success.”[27] This massive taking to Canadian streets in Italian colours is a fine example of the multiple ways soccer fandom produces identity: the fans are asserting they belong in Canadian public places as Canadians—and rejoicing in the identification with the Italian champions. The fluid semiotics of football are captured by communications scholar Francesco Ricatti and historian Matthew Klugman, who argue that “it is clear that the ethnic/national signifiers, such as the names of the teams and the flags brought at the stadium, should not be simply conflated with the defence of a fixed identity.”[28]

The potential belongings fostered by sport are particular and local, too, not just national. As sociologist Federico Genovesi points out, “solidarity grassroots football can provide opportunities for shared senses of belonging with the wider local community… [and] can play a vital role in the resistance of the liminality imposed by autochthonic politics of belonging.”[29] That is, organizing and playing community football is a way for a group to place themselves in public, in Canada, pushing out of the margins and into mainstream activity. It is an effective challenge to nativist thinking about who belongs, as the sport (although global) is seen as “Canadian” too.

Credit: CMI / Colin Timm.

Sociologist Greg Yerashotis points to interlinked urban, political, and group belongings as part of his calling to move “discussions on integration beyond instrumental perspectives of how sport influences youth’s settlement and toward considerations of how sport can facilitate multiple different forms of belonging in participants’ lives.”[30] These sets of complex and charged possible belongings negotiated through sport underscore the importance of paying attention to adaptation and integration at levels besides the national.

Keeping up with the fortunes of a favoured football club abroad, or most famously, cheering on a country of origin in the World Cup, brought a subtle but significant change to Canada’s sport and leisure culture. Fielding describes immigrants bringing “a sidewalk culture from regions where men mingled as groups and moved seamlessly between indoor and outdoor spaces. In sport, these streets fused with small businesses, the private homes, workplaces, and community centres to create an alternative geography of locations to watch, discuss, and play their favourite games.”[31] This was radically different from the existing general culture of leisure in Canada that did not include public spaces like streets or sidewalks, and it made for a contest around the space, even including policing.[32]

Adaptations of soccer are also an important part of cultural exchange, and in the North, indoor soccer has slowly made inroads, such that it was included in the Arctic Winter Games from 1980 to 2014. Sport scholar Vicky Paraschak notes that this was part of a movement on the part of the games to host events “more suited to native participants from the smaller communities.”[33] A local example for our Museum community in Halifax is the Mundialito, a little World Cup, run by Latispánica for the growing Latin American community.[34] Hosted at public sports facilities around Halifax, this again gives an example of soccer being the avenue for migrant communities to claim public space in their new home. Notably, in Canada and in the United States, as much as the migrant Latin American community comes together around football, the way it is practiced also reflects adaptation to new norms. Women, futboleras, take to the field, claiming a space that is, for many, culturally masculine and crafting a hybrid identity that reflects both an abiding love of the sport (brought from their old home) and an inclusion of women as players (adopted from their new home).[35] As one Latina woman told Herrera of this difference between soccer here and there, “[b]eing aware that things in Canada are different and then playing by those rules doesn’t make us hypocrites, it makes us conscious citizens.”[36]

Conclusion

Participating in soccer aids adaptation for migrants. From David Forsyth to Alphonso Davies, from the Muslim Youth Soccer League of London to indoor soccer in Nunavut, the game is founded on complex cultural exchanges and reciprocal adaptations. Some of the most significant benefits and adjustments happen out of the spotlight, however, as supporting or participating in soccer can push previous cultural norms and provide a venue for new social and professional networks. In this way, migrants can produce (and reproduce) many identities through soccer, including reinforcing or adding connections with cultural groups on one hand, while asserting belonging in Canadian public space on the other. The very act of embracing another country’s team is itself seen as not only acceptable but desirable within the constraints of sanctioned Canadian multiculturalism. Migrants build communities and make their homes in Canada through soccer.

- Marcelo Eduardo Herrera, ‘Soccer, Space, and Community Integration: Being and Becoming Canadian in London, Ontario through the World’s Game’ (London, ON, University of Western Ontario, 2018), 42, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses.↩

- Ramón Spaaij, ‘Beyond the Playing Field: Experiences of Sport, Social Capital, and Integration among Somalis in Australia’, Ethnic and Racial Studies 35, no. 9 (September 2012): 2, https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2011.592205.↩

- Greg Yerashotis, ‘Kickin’ It in “the Hood:” Soccer and Social Inclusion in Global Toronto’ (Doctor of Philosophy, Kinesiology and Physical Education, Toronto, ON, University of Toronto, 2022), 188.↩

- Alan Efetha, Oral History, Digital video, 25 May 2014, CMI Collection.↩

- Yerashotis, ‘Kickin’ It in “the Hood:” Soccer and Social Inclusion in Global Toronto’, 236.↩

- Herrera, ‘Soccer, Space, and Community Integration: Being and Becoming Canadian in London, Ontario through the World’s Game’, 33.↩

- Bachir Sirois-Moumni and Jean-Charles St-Louis, ‘La Star de soccer, figure de « la diversité » au Canada’, International Journal of Canadian Studies 61 (1 March 2023): 87, https://doi.org/10.3138/ijcs-2022-0005.↩

- Sirois-Moumni and St-Louis, 88.↩

- Rod Mickleburgh, ‘Nearly 70 Years on, an Act of Inclusion’, Globe and Mail, 11 January 2011, sec. A.↩

- Jason Beck, ‘1933 Chinese Students’, BC Sports Hall of Fame (blog), accessed 6 December 2024, https://bcsportshall.com/honoured_member/1933-chinese-students/.↩

- Mickleburgh, ‘Nearly 70 Years on, an Act of Inclusion’.↩

- Stephen Fielding, ‘Sporting Multiculturalism: Toronto’s Postwar European Immigrants, Gender, Diaspora, and the Grassroots Making of Canadian Diversity’ (PhD (History), Victoria, BC, University of Victoria, 2018), 30.↩

- Hugo Santos-Gómez, Immigrant Farmworkers and Citizenship in Rural California: Playing Soccer in the San Joaquin Valley, The New Americans : Recent Immigration and American Society (El Paso: LFB Scholarly Pub. LLC, 2014), 144.↩

- Canada Soccer, ‘Profile - David Forsyth’, 28 January 2020, https://canadasoccer.com/profile/.↩

- Efetha, Oral History.↩

- Efetha.↩

- Herrera, ‘Soccer, Space, and Community Integration: Being and Becoming Canadian in London, Ontario through the World’s Game’, 104–5.↩

- Herrera, 104.↩

- Herrera, 69.↩

- Martin Lange, Friedhelm Pfeiffer, and Gerard J. Van Den Berg, ‘Integrating Young Male Refugees: Initial Evidence from an Inclusive Soccer Project’, Journal for Labour Market Research 51, no. 1 (December 2017): 9, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12651-017-0234-4.↩

- Herrera, ‘Soccer, Space, and Community Integration: Being and Becoming Canadian in London, Ontario through the World’s Game’, 68–69.↩

- Herrera, 38–39.↩

- Fielding, ‘Sporting Multiculturalism: Toronto’s Postwar European Immigrants, Gender, Diaspora, and the Grassroots Making of Canadian Diversity’, 105.↩

- Fielding, 109.↩

- Fielding, 105–6.↩

- ‘Canada Has Supporters of All 32 FIFA Soccer Teams’, The National (Toronto, ON: CBC, 12 June 2014).↩

- Fielding, ‘Sporting Multiculturalism: Toronto’s Postwar European Immigrants, Gender, Diaspora, and the Grassroots Making of Canadian Diversity’, 168.↩

- Francesco Ricatti and Matthew Klugman, ‘“Connected to Something”: Soccer and the Transnational Passions, Memories and Communities of Sydney’s Italian Migrants’, The International Journal of the History of Sport 30, no. 5 (March 2013): 479, https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2013.770735.↩

- Federico Genovesi, ‘Spaces of Football and Belonging for People Seeking Asylum: Resisting Policy-Imposed Liminality in Italy’, International Review for the Sociology of Sport 59, no. 1 (February 2024): 84, https://doi.org/10.1177/10126902231179624.↩

- Yerashotis, ‘Kickin’ It in “the Hood:” Soccer and Social Inclusion in Global Toronto’, 306.↩

- Fielding, ‘Sporting Multiculturalism: Toronto’s Postwar European Immigrants, Gender, Diaspora, and the Grassroots Making of Canadian Diversity’, 42.↩

- Fielding, 211–12.↩

- Vicky Paraschak, ‘Sport Festivals and Race Relations in the Northwest Territories of Canada’, in Sport, Racism and Ethnicity, ed. Grant Jarvie (London: Falmer, 1995), 64.↩

- Javier Ortega-Araiza, ‘Amid a Booming Latin American Population in Canada, This Halifax Group Is Building Community from the Ground Up’, Canadian Press, 7 February 2024, sec. Wire Feed.↩

- Paul Cuadros, ‘We Play Too: Latina Integration through Soccer in the “New South”’, Southeastern Geographer 51, no. 2 (June 2011): 228, https://doi.org/10.1353/sgo.2011.0021; Herrera, ‘Soccer, Space, and Community Integration: Being and Becoming Canadian in London, Ontario through the World’s Game’, 54–55.↩

- Herrera, ‘Soccer, Space, and Community Integration: Being and Becoming Canadian in London, Ontario through the World’s Game’, 59.↩