by Jan Raska, PhD, Historian

(Updated October 22, 2020)

Introduction

Before the arrival of Europeans, Algonquin and Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) nations were the primary inhabitants along the St. Lawrence River (known in Mohawk as Kaniatarowanenneh, meaning “big waterway”) and the area later encompassing Quebec City (known in Algonquin as Kébec, meaning “where the river narrows”). In 1535, French explorer Jacques Cartier discovered a Haudenosaunee village, Stadacona, where some 1,000 inhabitants lived primarily from cultivating corn, fishing, and hunting. In 1608, French explorer Samuel de Champlain established a trading post and habitation, and named it Québec. Following several military assaults on the town throughout the next 150 years, it was conquered by the British in 1759. Successfully repelling an American invasion in 1775-1776, the town remained a part of British North America until Canadian Confederation in 1867.[1]

Immigration and the “population flottante” profoundly marked the demographic, sociocultural, and economic fibres of Quebec City. The migrating local populace and incoming European immigrants had a major impact on the development of institutions, trade, and modes of transportation. This report argues that within Quebec City, one site was shaped by all three aforementioned areas: the Port of Quebec. In turn, the port later helped to diversify the sociocultural and political composition of the city. By 1850, forty percent of the city’s population was Anglophone with the Port of Quebec handling two-thirds of all European immigration to British North America (BNA).[2] At the time, Quebec City was home to the only large ocean port. Traditionally, the travel season began in mid-April after a long winter in which the St. Lawrence River lay frozen. Ships that were outfitted for travel in March in the harbours of Europe were often held up at La Traverse below Quebec City due to strong winds and high tides. From spring to fall, Quebec City opened up to the importation of goods and newcomers, while Canadian businesses and entrepreneurs sent their products off to the markets of Europe.[3]

Since the French regime, Quebec City had been home to Canada’s principal port, but began to decline in influence in the second-half of the nineteenth century. Due in part to the gradual reduction of the timber trade, an improvement of the ship channel to Montreal, and the rapidly-developing continental communications networks across North America, the Port of Quebec witnessed a decline in ocean shipping traffic and construction of wooden sailing vessels. In the twentieth century, local politicians, business leaders, immigration officials, and European immigrants were instrumental in shaping the port’s facilities, thereby increasing the flow of ‘human’ traffic and the port’s significance as a major Canadian shipping and transportation hub.[4]

Establishing the Port of Quebec

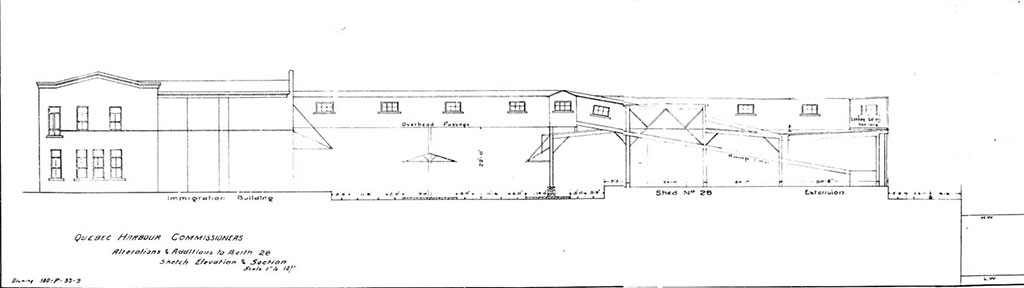

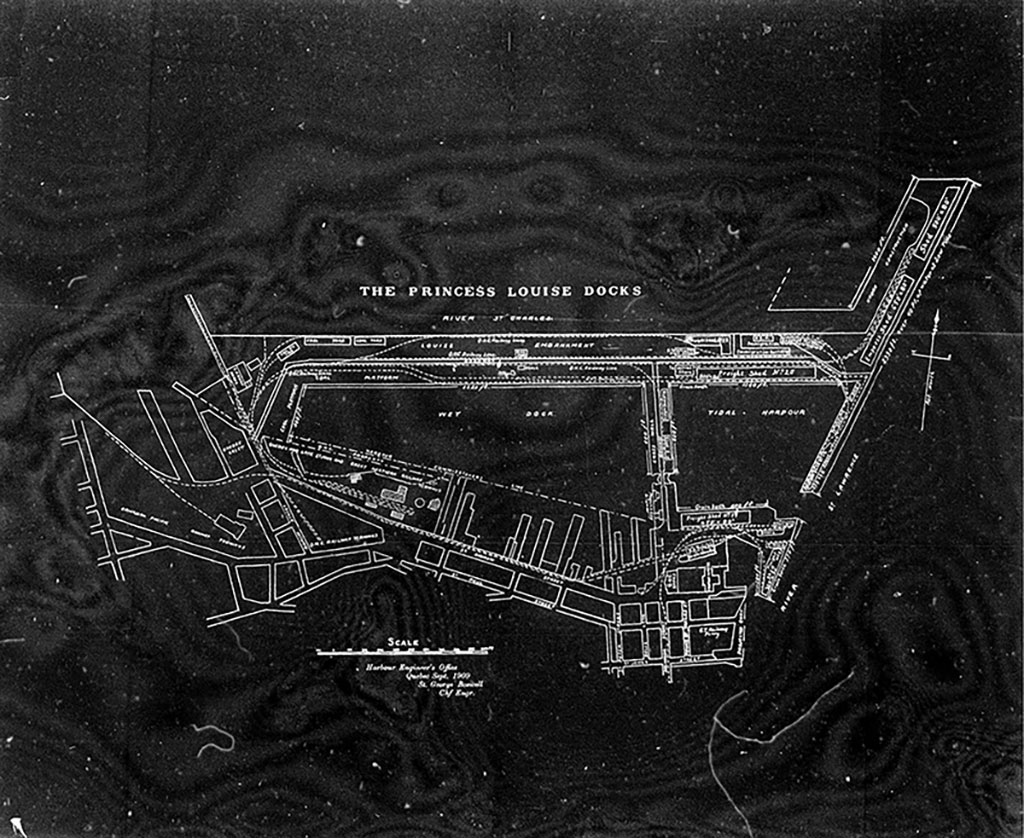

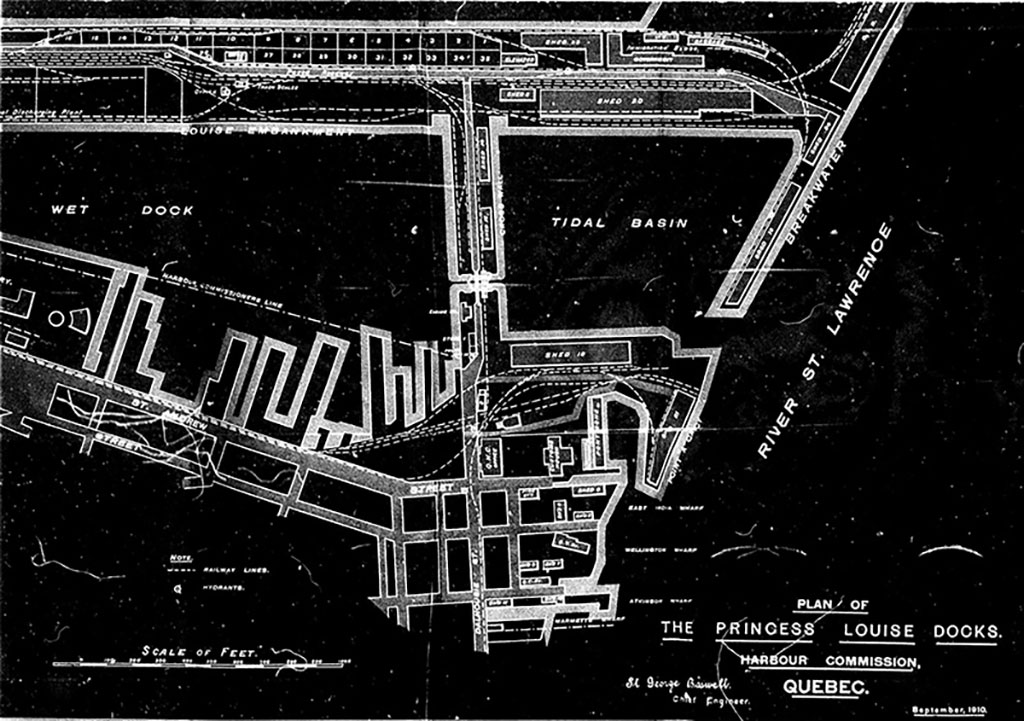

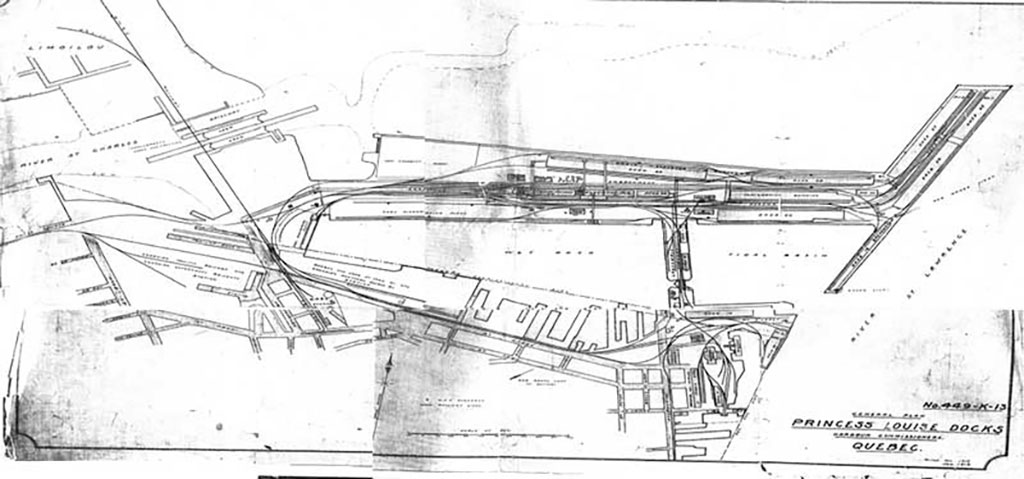

In 1858, the Quebec Harbour Commission (QHC) was created to improve the city’s marine facilities. With transatlantic traffic through Montreal’s harbour rapidly expanding, Quebec City’s economic dominance in the St. Lawrence began to wane by the 1870s. However, immigration remained robust. From 1869 to 1889, 538,137 immigrants landed at Quebec City in comparison to 91,910 at Halifax. During this period, the Bassin Louise (Louise Basin) opened and the adjacent Pointe-à-Carcy wharf was built. In 1875, the Canadian government dissolved the Trinity House of Quebec – which was responsible for maintaining order at the port – and vested its responsibilities in the QHC. Between the mid-1870s and 1890, the QHC constructed a large wet dock, the only one if its type in North America, ensuring that the Port of Quebec maintained a significant share of the Canadian overseas trade. During the same period, Canadian immigration officials expanded the port’s immigration facilities to handle the growing number of arrivals. The expansion of the Bassin Louise and the Princess Louise docks did not alter the growing flow of traffic to Montreal. In 1903, the QHC began work on a second phase of port expansion to serve two other important economic sectors: western grain exports, and transatlantic passenger traffic. The expanded Princess Louise docks necessitated an increase in passenger traffic, but failed to increase exports.[5]

Credit: Library and Archives Canada, Immigration Branch fonds, RG 76, vol. 667, file C1596, pt. 1

Credit: Library and Archives Canada, Immigration Branch fonds, RG 76, vol. 683, file 802, pt. 5

Credit: Library and Archives Canada, Immigration Branch fonds, RG 76, vol. 683, file 802, pt. 5

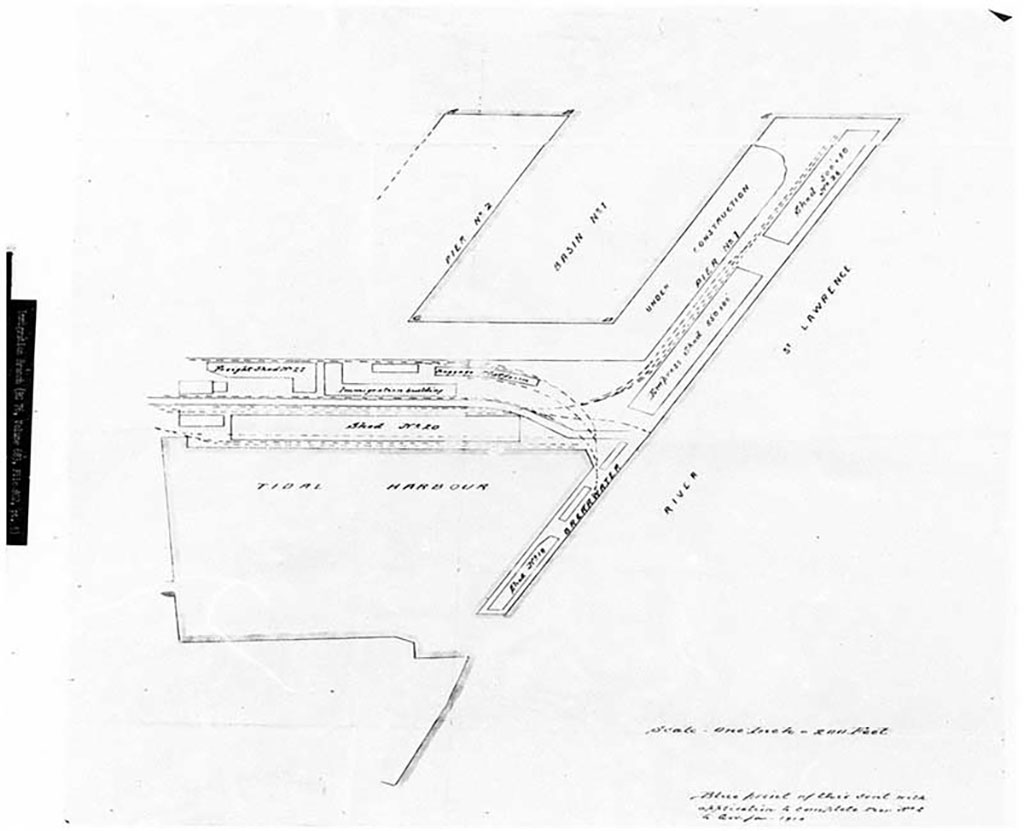

Credit: Library and Archives Canada, Immigration Branch fonds, RG 76, vol. 683, file 802, pt. 8

Credit: Library and Archives Canada, Immigration Branch fonds, RG 76, vol. 683, file 802, pt. 9

Credit: Library and Archives Canada, Immigration Branch fonds, RG 76, vol. 684, file 802, pt. 16

Credit: Library and Archives Canada, Immigration Branch fonds, RG 76, vol. 684, file 802, pt. 16

Renovations for the Improved Reception and Accommodation of Arriving Immigrants

During the transatlantic passenger travel season of 1907, improvements to the reception and accommodation of immigrants became a necessity. Unable to secure the necessary funds from Ottawa, immigration officials negotiated an agreement with the Canadian Pacific Railway Company (CPR) whereby they would carry out the necessary changes for a sum totalling $11,649.93.[6] A year later, representatives of the Allan Lines of Royal Mail Steamships complained that railway tracks at the immigration facility at the Port of Quebec were not prepared for the upcoming travel season. Similarly, baggage handling was poorly arranged with transportation companies working on a narrow platform that led to travel delays.[7] With these complaints in mind, the QHC undertook to improve the railways platforms at the Port of Quebec.[8] In an effort to prevent immigrants from “moving about” between the immigration shed and the “Empress” shed, immigration officials introduced new directions for the processing of passengers disembarking from Empress steamers. Second class passengers disembarked at the same time as their baggage was unloaded. Once they had boarded trains heading westward, passengers arriving in third class were disembarked and their luggage was made available for train travel. With an expanded platform and baggage handling facilities, immigration officials at the Port of Quebec sought to streamline passenger disembarkation. Transportation companies disapproved of these new instructions and claimed that delays of more than four hours could be expected in getting trains to leave Quebec. Immigration officials disagreed with these assertions.[9] Two years later, a fire razed a grain shed located in the Port of Quebec’s Pointe-à-Carcy sector. This tragic event did not slow down immigration through the Port Quebec. Once repairs were concluded, the QHC chose to build its new offices at the location.

Credit: John Woodruff / Library and Archives Canada / PA-021672

Credit: Topley Studio / Library and Archives Canada / PA-010275

Credit: William James Topley / Library and Archives Canada / PA-010278

Credit: William James Topley / Library and Archives Canada / PA-010283

Public Health and Prohibiting “Unfit” Immigrants from Entering Canada

In an address to the Annual Congress of the Canadian Public Health Association, J.D. Pagé, Chief Medical Officer, Port of Quebec, and Medical Superintendent, Quebec City Immigration Hospital (locally referred to as Hôpital du Parc Savard (Park Savard Hospital)) noted that the “medical inspection of immigrants must be considered in the present evolution of Canada as a problem of capital importance from a public health point of view.” The chief medical officer illustrated that while local health authorities devoted their attention to the conservation and improvement of personal health through preventive means and promoting fitness, federal officials were tasked with a “heavier responsibility” to control the numbers of “unfit” immigrants arriving in Canada. In 1906, the Canadian government enacted a new Immigration Act, the first major legislative overhaul pertaining strictly to immigration in almost four decades. Under the new Act, inspecting officers at ports of entry had the authority to prohibit entry based on an applicants’ health, finances, or character. They also had discretionary authority to use some of the Act’s vague clauses to bar individuals who they deemed undesirable due to cultural background or ethno-racial identity. The 1906 Act was primarily used to prevent the entry of immigrants of African or Asian descent, political undesirables such as anarchists, mentally or physically disabled persons, and any individual likely to become a ‘public charge.’

Four years later, the federal government expanded the list of prohibited immigrants and increased immigration officials’ discretionary powers in selecting, admitting or preventing immigrants from entering Canada. The 1910 Immigration Act also made inadmissible individuals who were deemed to be unsuitable to Canada’s climate. The designation of “climatic unsuitability” was targeted primarily against racialized groups including applicants of African or Asian descent. This permitted Canadian officials to argue – speciously - that there was no “colour bar” in Canadian legislation. This kind of veiled, discretionary authority enjoyed increased protection from scrutiny under the 1910 Act, as the federal and provincial judiciary was prevented from reviewing or reversing the rulings of the federal minister responsible for immigration. Following the restrictive measures put in place in the 1906 and 1910 Immigration Acts to prevent the admission of ‘undesirables’ and the medically unfit, 80 to 90 percent of detentions and rejections were due to eye troubles, mostly trachoma among continental European immigrants who were a majority of those detained at Canadian ports of entry.[10]

Credit: William James Topley / Library and Archives Canada / PA-010436

Credit: William James Topley / Library and Archives Canada / PA-010388

Credit: William James Topley / Library and Archives Canada / PA-010389

Credit: William James Topley / Library and Archives Canada / PA-010390

Credit: William James Topley / Library and Archives Canada / PA-010483

Credit: William James Topley / Library and Archives Canada / PA-010279

Credit: William James Topley / Library and Archives Canada / PA-010282

Credit: William James Topley / Library and Archives Canada / PA-010384

Improvements to Immigration and Transportation Infrastructure

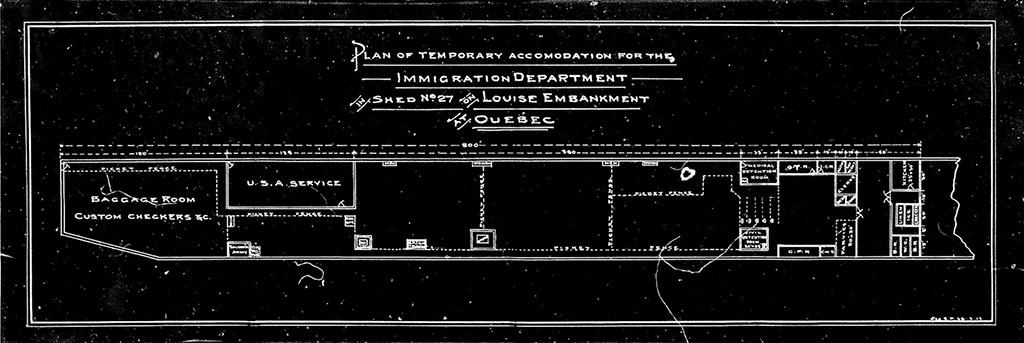

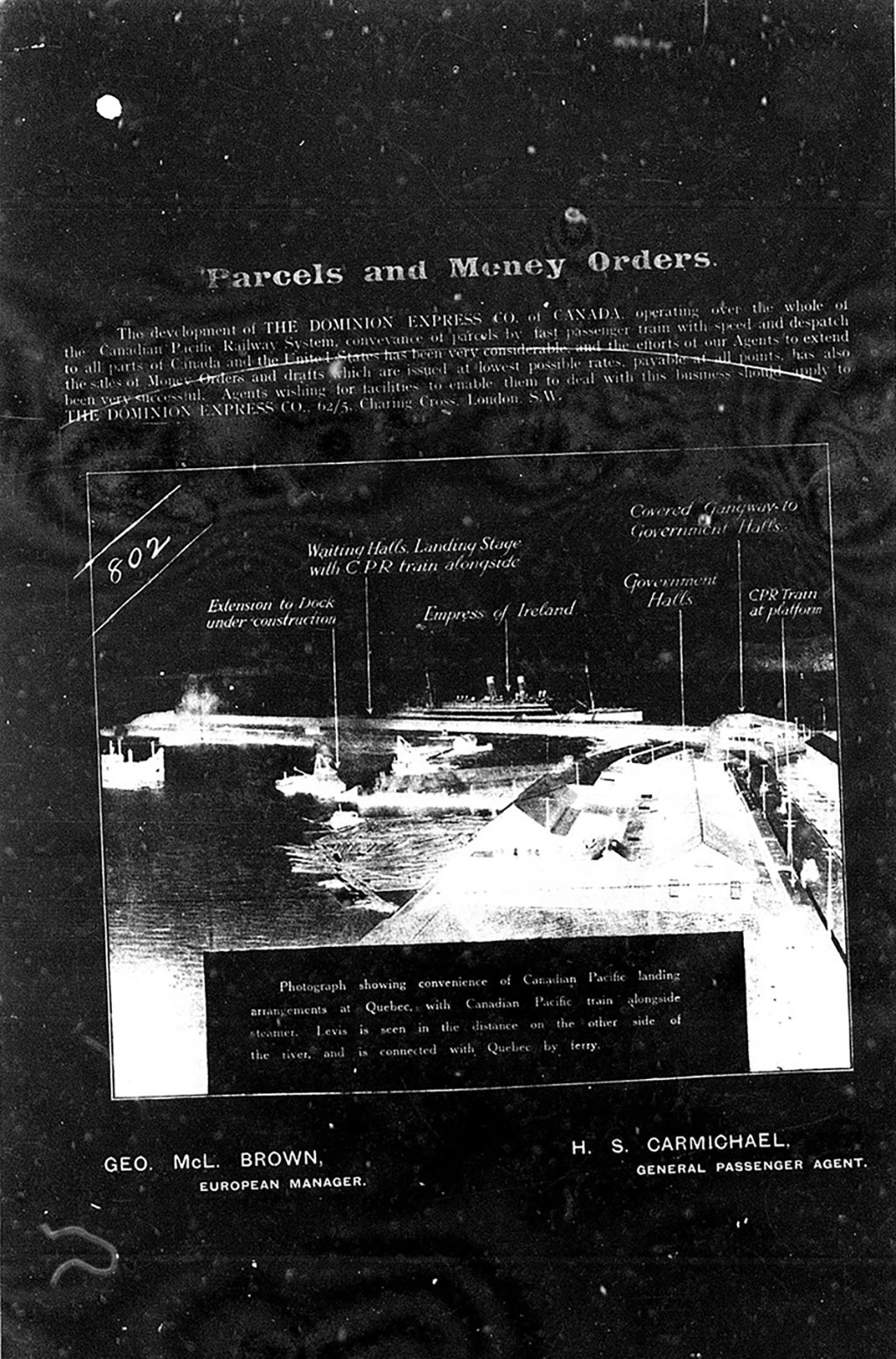

As immigration officials were concerned with the health of disembarking immigrants at the Port of Quebec, improvements to the site’s immigration and transportation infrastructure were underway. In December 1912, CPR began to demolish the existing immigration building at the port. While the demolition was ongoing, immigration officials occupied the offices of the United States Immigration Service on the ground floor. Later, the QHC approved the use of freight shed no. 27 as a temporary immigration facility until the new building was erected at Pier 1 on the Louise Embankment later in 1913. Shed no. 27 was originally built to serve the Allan Line’s transportation needs. The CPR agreed to make the necessary alterations and partitions to the building on behalf of the Department of Public Works with repayment for its services to take place at a later date. The CPR’s outlay of shed no. 27 was to cost no more than $3,000. The freight shed to be used as a temporary immigration facility was 800 feet in length and consisted of a baggage room and U.S. Immigration Service office on its western side, and separate civil and medical detention rooms, transportation companies’ offices, washrooms, a kitchen, and quarters on its eastern side. Renovations were finished prior to the arrival of the first passenger vessel in the spring of 1913.[11] With a considerable number of immigrants arriving in Canada at the Port of Quebec, the Department of Agriculture felt it necessary to station an agent at the immigration facility in April 1913.[12] Two months later on 16 June, a hurricane struck the Port of Quebec and damaged the immigration facility. While the devastation could be found across the city, shed no. 27 was badly damaged with broken windows and doors, and the offices were left uninhabitable.[13]

Credit: William James Topley / Library and Archives Canada / PA-010382

Credit: William James Topley / Library and Archives Canada / PA-010386

Credit: William James Topley / Library and Archives Canada / PA-010274

Credit: William James Topley / Library and Archives Canada / PA-010451

Provincial Authorities and Voluntary Service Agencies Request Office Space

With immigration to Canada through the Port of Quebec rising considerably, provincial governments requested office space at the new immigration building under construction in an effort to entice settlers. The government of Nova Scotia attempted to station a representative at the port in an effort to promote settlement in the province, and assist immigrants in reaching their final destinations in Nova Scotia. Immigration officials also had to accommodate voluntary agencies and religious groups who sought office space at the Port of Quebec. Superintendent of Immigration, W.D. Scott, noted that if all requests for space were granted “there would be no space left for the immigrants.” Scott concluded that provincial government representatives from Ontario and Nova Scotia would share an office, while any future requests from the other provinces would share the same space.[14] In the case of religious groups, five denominations shared office space at the Port of Quebec: Roman Catholic, Presbyterian, Bible Society, Methodist, and Anglican. They were later followed by the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), and the Jewish Immigrant Aid Society (JIAS). In the summer of 1913, a two-storey immigration facility was opened at the Port of Quebec. In September, immigration officials in Ottawa declined a request from the Dominion Immigration Agent at the Port of Quebec, J.P. Stafford, to appoint additional guards to the immigration facility. Ottawa believed that immigration would decline since only agriculturalists and domestics were permitted to enter Canada. During the travel season, civil detentions were looked after by hospital staff at Savard Park.[15] Immigration officials at the Port of Quebec were proven wrong. In 1913, 400,870 immigrants arrived in Canada representing 5.3 percent of the country’s population. The Port of Quebec processed the majority of these arrivals. The year marked the height of immigration to Canada during the twentieth century.

Credit: William James Topley / Library and Archives Canada / PA-010283

Credit: National Film Board of Canada. Phototèque / Library and Archives Canada / PA-048700

Credit: National Film Board of Canada / Library and Archives Canada / PA-048703

The Port of Quebec and the First World War

Prior to the outbreak of hostilities in Europe in the summer of 1914, the federal government recognized that the Port of Quebec was one of the sites likely to be of interest to the enemy. Military officials were concerned with the possibility that German submarines in the Atlantic could attempt to restrict access or outright embargo the port to commercial and military vessels. In order to fend off all threats including the possibility of mines in the St. Lawrence River between Île d’Orleans and the south shore, two batteries were built at Pointe-de-la-Martinère, east of Lévis. The Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) was invited to implement a system whereby the military would board ships and inspect their personnel and cargo as they headed up the river towards the Port of Quebec. The RCN was also responsible for marshalling convoys destined for Europe.[16]

Following Canada’s declaration of war against Germany in September 1914, the Port of Quebec became a boarding point for soldiers and food supplies destined for Europe. On September 14, Colonel Eugène Fiset, Deputy Minister of Militia and Defence, asked the Ministry of the Interior for permission for the militia’s medical authorities to use the Louise Basin immigration facilities at the port of Quebec. The purpose of this request was to store medical supplies for the foreign contingent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, and to provide accommodation for a small number of personnel prior to embarkation. The department required enough space for 1,000 to 1,500 tonnes of supplies.[17] The storage of these supplies did not hinder the work of the immigration officials or the landing of passengers. The dining room and kitchen were placed at the disposal of the District Commanding Officer.[18] Later, Major General Sam Hughes, Minister of Militia and Defence, ordered the military authorities in Quebec City to paint the immigration facility’s baggage room with alabaster or white kalsomine in order to make the room brighter for drilling purposes. Immigration officials in Ottawa did not object to the alteration of their building.[19]

Hiring Additional Personnel to Manage the Flow of Immigration Traffic

Less than a year after the First World War, Dr. J.D. Pagé decided that in the future two separate gangways would be used in an effort to prevent first class passengers from mixing with their fellow travelers in steerage. Pagé’s proposed change of August 1919 was the result of an incident aboard SS Scotian where passengers were able to come ashore before passing inspection. Due to the existence of only one gangplank, confusion between the ship’s passengers escalated to a point beyond the control of immigration officials.[20] In a letter to his superiors in Ottawa, Pagé noted that the new quarters at the immigration building at the Port of Quebec required a nurse who upon being hired would be paid $100 per month, while a "maid" who was deemed as a necessity, would be employed with a salary of $40 each month. Both positions were to be filled in an effort to staff multiple wards.

The northern ward consisted of quarters comprising 90 beds, a lavatory opening in the hall with six wash basins, five washrooms, and three shower baths. Ward D contained thirty-six beds divided into three sections and included rooms dedicated to special medical treatment, diet, writing and recreation rooms. Ward F was divided into four sections opening onto the verandah with 66 beds, five washrooms, six wash basins, and five shower baths. The Acting Dominion Immigration Agent questioned Ottawa’s insistence that no more guards were needed to handle the duties associated with the arrival of passengers and detainees. Staff at the Port of Quebec was often required to request the assistance of the Canadian Militia to handle the flow of passenger traffic. While Pagé sought additional approval to hire staff for the immigration building, the Canadian Militia stationed at the site during wartime agreed to hand over control of the premises to the Department of Immigration and Colonization following the armistice. While travellers continued to arrive at the Port of Quebec, the Acting Dominion Immigration Agent indicated to his superiors that for several months, no eastbound ships had stopped at Quebec City. Detainees scheduled to be deported for Europe were unable to leave. It was Pagé’s hope that immigration officials in Ottawa would resolve the matter with the steamship companies.[21]

Lacking Detention Facilities at the Port of Quebec

In September 1919, immigration officials at the Port of Quebec were notified by the Canadian Patriotic Fund that many of the immigrants entering Canada, especially women and soldiers’ dependents, did not have any money with them and were stranded on arrival. Although immigrants without sufficient means were not permitted to enter Canada, the Canadian Militia which had until recently been responsible for the building allowed these detained immigrants to enter the country due to a lack of detention space. Individuals found not to be within the requirements of the Immigration Act were held and forwarded to detention quarters in Montreal, either on the ships they came into Canada with or by train under the supervision of an official.[22]

Immigration Officials and Transportation Companies Dispute Responsibility for Sick and Infirm Immigrants

In the fall of 1919, the practice of detaining immigrants at Montreal was discontinued as larger movements of immigrants continued to arrive through Quebec City. Detainees were held in quarters on the second floor of the immigration building. Steamship companies and Canadian immigration officials disagreed on how to handle sick, infirm, and pregnant travellers. At the Port of Quebec, officials argued that transportation companies were financially responsible for all expenses related to any sickness or condition brought to Canada aboard a vessel docked at the city. In one particular case, immigration authorities and representatives of the Compagnie canadienne transatlantique squabbled over who was to pay a pregnant woman’s hospital bill. On 19 September, Guiseppa Briffa, a Maltese immigrant arrived in Quebec City aboard SS Californie. Due to complications with an abortion aboard ship, she was admitted to the Hotel-Dieu Hospital for treatment. Her stay cost $21 dollars. While Pagé claimed it was the steamship company’s duty to pay the hospital bill after bringing Briffa to Canada, the Compagnie canadienne transatlantique informed the Department of Immigration and Colonization in Ottawa that she had been pregnant two and half months before her abortion aboard ship. Ship officials claimed that prior to departure, they had “obviously no means of knowing her condition” which led to the abortion, and her husband did not have the means to pay the bill. The steamship company argued that the Department could not claim that it had “failed to exercise proper vigilance or care in bringing the woman to Canada.”[23] While officials and transportation companies squabbled over the costs involved in landing immigrants in Canada, section 34 (Medical Treatment of Sick and Disabled Passengers) of the 1910 Immigration Act noted that if the passenger was not in a position to defray the costs of any expenditure associated with their passage, the transportation company would be held liable.[24]

Conclusion

From the eighteenth century onwards, Quebec’s demographic, sociocultural, and economic fibres were profoundly marked by immigrants from the United Kingdom, Scandinavia, and Central and Eastern Europe. These movements of immigrants had a major impact on the development of institutions, trade, and modes of transportation. Within Quebec, one site was shaped by all three aforementioned areas: the Port of Quebec. In turn, the port later helped to diversify the sociocultural and political composition of the city. Since its inception, the Port of Quebec’s main purpose was economic trade; in particular the export of goods overseas, and transportation. Immigration was an important economic activity in the latter area through transatlantic passenger travel. While transatlantic transportation companies sought to increase their business in bringing travelers to Canada, federal immigration officials regulated the movement of passenger travel – through admission, detention, denial, and quarantine of individual arrivals – all in an effort to maintain Canada’s sociocultural composition as a Eurocentric settler country. After Confederation, Immigration Acts, Orders-in-Council, and departmental regulations all served Canada’s need to control immigration, however, the Port of Quebec’s infrastructure also shaped how immigration legislation, and immigrant processing were conducted.

By the 1850s, Quebec City was home to BNA's only large ocean port. As a result of this infrastructure and geographical proximity to Europe, its port handled two-thirds of all European immigration to BNA. From spring to fall, Quebec City opened up to the importation of goods and newcomers, while Canadian businesses and entrepreneurs sent their products off to the markets of Europe. In both New France and BNA, as well as Canada after 1867, Quebec City was home to Canada’s principal port, but began to decline in influence in the second-half of the twentieth century. Due in part to the gradual reduction of the timber trade, an improvement of the ship channel to Montreal, and the rapidly developing continental communications networks across North America, the Port of Quebec witnessed a decline in ocean shipping traffic and construction of wooden sailing vessels. In the twentieth century, local politicians, business leaders, immigration officials, and European immigrants were instrumental in shaping the port’s facilities, thereby increasing the flow of ‘human’ traffic and the port’s significance as a major Canadian shipping and transportation hub.

- Native Land Digital, “Native Land,” https://native-land.ca/; Port Québec, “Then and Now: 1535 to 1899,” https://www.portquebec.ca/en/about/port-authority/history; “Marc Vallières, “Quebéc City,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, last edited 12 March 2019, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/quebec-city.↩

- David-Thierry Ruddel, Québec: L’évolution d’une ville coloniale, 1765-1832 (Hull : Musée canadien des civilisations, 1991), 31; Robert J. Grace, “A Demographic and Social Profile of Quebec City’s Irish Populations, 1842-1861,” Journal of American Ethnic History 23.1 (2003): 55. One-quarter of the total urban population was composed of Irish immigrants and their children. See Robert J. Grace, “Irish Immigration and Settlement in a Catholic City: Quebec, 1842-61,” Canadian Historical Review 84.2 (2003): 217.↩

- Rudolphe Vincent, Quebec: Historic City (Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1996), 17.↩

- For an overview of the Port of Quebec, see Pierre Camu, “Le déclin du Port de Québec dans la deuxième moitié du XIXe siècle,” Northern Mariner/le marin du nord 20.3 (2010): 251; Charles N. Forward, “The Development of Canada’s Five Leading National Ports,” Urban History Review 10.3 (1982): 26. A sizable amount of literature exists on the Port of Quebec, see Albert Faucher, “The Decline of Shipbuilding at Quebec in the Nineteenth Century,” Canada Journal of Economics and Political Science 23.2 (1957): 195-215; Judith Fingard, “The Decline of the Sailor as a Ship Labourer in 19th Century Timber Ports,” Labour/Le Travailleur 2 (1977): 35-53; Forward, “The Development of Canada’s Five Leading National Ports;” Judith Fingard, Jack in Port (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1982); Grace, “Irish Immigration and Settlement in a Catholic City;” Grace, “A Demographic and Social Profile of Quebec City’s Irish Populations, 1842-1861;” Christopher Andreae, “Evolution of the Port of Quebec, 1858-1936” (PhD diss., University of Western Ontario, 2006); Marc Vallières and Yvon Desloges, “Les échanges commerciaux de la colonie laurentienne avec la Grande-Bretagne, 1760-1850,” Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française 61.3-4 (2008): 425-467; Serge Rouleau, “Un regard archéologiques sur le port colonial français de Québec,” Archéologiques 22 (2009): 208-223; Camu, “Le déclin du Port de Québec dans la deuxième moitié du XIXe siècle;” Keith Mercer, “Northern Exposure: Resistance to Naval Impressment in British North America, 1775-1815,” Canadian Historical Review 91.2 (2010): 199-232.↩

- Andreae, “Evolution of the Port of Quebec, 1858-1936.” See abstract.↩

- Library and Archives Canada (hereafter LAC), Immigration Branch (hereafter IB) fonds, RG 76, vol. 683, file 802, pt. 4 “Immigration Building, Quebec City, Quebec,” letter from L.M. Fortier for Superintendent of Immigration, Department of the Interior to Secretary, Department of Public Works, 23 November 1907.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 683, file 802, pt. 4 “Immigration Building, Quebec City, Quebec,” letter from G.H.M., Allan Lines of Royal Mail Steamships to W.D. Scott, Superintendent of Immigration, Department of the Interior, 14 April 1908.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 683, file 802, pt. 4 “Immigration Building, Quebec City, Quebec,” letter from William Stitt and George C. Wells, Canadian Pacific Railway Company, Montreal to W.D. Scott, Superintendent of Immigration, Department of the Interior, 15 February 1909.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 683, file 802, pt. 5 “Immigration Building, Quebec City, Quebec (plans),” letter from George Hodge, Superintendent, Montreal to C. Murphy, Superintendent, 19 June 1909.↩

- J.D. Pagé, “The Medical Inspection of Immigrants on Shipboard,” Public Health Journal 3.1. (1912): 25; K. Tony Hollihan, “‘A brake upon the wheel’: Frank Oliver and the Creation of the Immigration Act of 1906,” Past Imperfect 1 (1992): 96, 106-107; Ninette Kelley and Michael Trebilcock, The Making of the Mosaic: A History of Canadian Immigration Policy (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010), 131-133, 137-138; Barbara Roberts, Whence they Came: Deportation from Canada 1900-1935 (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1998), 57-58; Valerie Knowles, Strangers at Our Gates: Canadian Immigration and Immigration Policy 1540-2006 (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2007), 85-86.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 683, file 802, pt. 8 “Immigration Building, Quebec City, Quebec (plans),” letter from J.P. Stafford, Acting Dominion Immigration Agent, Quebec to W.D. Scott, Superintendent of Immigration, Department of the Interior, 18 January 1913; LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 683, file 802, pt. 8 “Immigration Building, Quebec City, Quebec (plans),” letter from W.D. Scott, Superintendent of Immigration, Department of the Interior to A. Johnston, Deputy Minister, Department of Marine and Fisheries, 30 January 1913.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 683, file 802, pt. 9 “Immigration Building, Quebec City, Quebec (plans),” letter from J. Daggett, Secretary for Agriculture to W.D. Scott, Superintendent of Immigration, Department of the Interior, 7 April 1913.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 683, file 802, pt. 9 “Immigration Building, Quebec City, Quebec (plans),” letter from J.P. Stafford, Dominion Immigration Agent, Quebec to W.D. Scott, Superintendent of Immigration, Department of the Interior, 17 June 1913.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 684, file 802, pt. 11 “Immigration Building, Quebec City, Quebec (plans),” memorandum from W.D. Scott, Superintendent of Immigration, Department of the Interior to Mr. Mitchell, 23 April 1914.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 684, file 802, pt. 10 “Immigration Building, Quebec City, Quebec,” letter from J.A. Coté, Acting Deputy Minister, Department of the Interior to J.P. Stafford, Dominion Immigration Agent, 26 September 1913.↩

- Serge Bernier et al., Military History of Quebec City, 1608-2008 (Montreal: Art Global, 2008), 258-260.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 684, file 802, pt. 12 “Immigration Building, Quebec City, Quebec, (plans),” letter from Colonel Eugène Fiset, Deputy Minister, Department of Militia and Defence to Deputy Minister, Department of the Interior, 14 September 1914.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 684, file 802, pt. 12 “Immigration Building, Quebec City, Quebec, (plans),” letter from W.D. Scott, Superintendent of Immigration, Department of the Interior to J.P. Stafford, Dominion Immigration Agent, 6 November 1914.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 684, file 802, pt. 12 “Immigration Building, Quebec City, Quebec, (plans),” telegram from W.D. Scott, Superintendent of Immigration, Department of the Interior to J.H. Stafford, Dominion Immigration Agent, 16 December 1914.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 665, file C1077 “Inspection of Immigrants,” letter from J.D. Pagé, Acting Dominion Immigration Agent to L. Fontaine, CPOS Agent, 5 August 1919.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 665, file C1077 “Inspection of Immigrants,” letter from J.D. Pagé, Acting Dominion Immigration Agent to Department of Immigration and Colonization, September. 1919.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 665, file C1077 “Inspection of Immigrants,” Letter from Dr. J.D. Pagé, Acting Dominion Immigration Agent to W.M. Bancroft, Joint Honourary Treasurer, Canadian Patriotic Fund, 29 September 1919.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 665, file C1077 “Inspection of Immigrants,” letter from Pringle & Guthrie, to F.C. Blair, Secretary, Department of Immigration and Colonization, 12 Nov. 1919. Luigi (age 31) and Giuseppa Briffa (age 22) were born in Malta and sailed to Canada via Le Havre, France. Luigi was a plater by occupation. The Briffas brought $100 in cash to Canada. Immigration officials believed it had a value of fifty Canadian dollars. Eventually, Canadian officials attempted to get a portion of these funds to settle the hospital bill. It is not clear whether they were successful.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 665, file C1077 “Inspection of Immigrants,” letter from J.I. Little, Commissioner to Dr. J.D. Pagé, Acting Dominion Immigration Agent, Department of Immigration and Colonization, 7 October 1919.↩