by Jan Raska, PhD, Historian

(Updated August 21, 2020)

Forcible Displacement of Polish Nationals to Labour Camps in the Soviet Union

In August 1939, Germany and the Soviet Union concluded a treaty of non-aggression and neutrality. The Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Soviet Union – commonly referred to as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact – also delineated spheres of interest between both parties. The following month, German and Soviet forces invaded Poland and split the country into two zones according to the terms of their agreement. Between September 1939 and the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, Soviet forces – hostile to the Polish population and its culture – imprisoned some 500,000 Polish nationals and deported a further 500,000 individuals in four waves of mass deportations from eastern Poland to labour camps in Siberia.

In July 1941, Polish and Soviet officials concluded an agreement whereby thousands of Polish civilians and prisoners of war were released from Soviet camps. A Polish army was established under the command of General Wladyslaw Anders, from those Poles who had been forced to move eastward. In March 1942, Soviet officials agreed to move the Polish army to Iran after the Anglo-Soviet invasion of the country. In search of food and security, civilian deportees, including women and unaccompanied minors, followed the Polish unit to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, before reaching Iran. While ‘Anders’ Army’ eventually made its way to Palestine where it became the bulk of the Polish 2nd Corps, some 18,000 children orphaned or separated from their parents during the Soviet invasion of their homeland or in the Siberian camps, were sent across the world to East Africa, India, New Zealand, and Mexico.[1]

Some of these minors reached refugee camps in Uganda, Kenya, North Rhodesia (now Zambia), and Tanganyika (now Tanzania). A group of Catholic Polish orphans resided in Tengeru, home to one of Tanganyika’s largest camps for European displaced persons (DPs). Upon hearing of their plight, the Archbishop of Montreal, Joseph Charbonneau, decided to initiate a plan to sponsor their permanent resettlement in Canada.[2]

Canadian Catholic Church Proposes a Plan to Resettle Polish Orphans in Canada

The proposal to bring Polish orphan children to Canada was formulated while another group of unaccompanied children were resettled in the country. In 1942, the Canadian Jewish Congress received permission from the Canadian government, through Order-in-Council P.C. 1647, to bring approximately 1,000 Jewish children residing in Vichy France to Canada. Due to German occupation of the region, the scheme lay dormant until it was resurrected in 1947. Two years later, 1,123 Jewish orphans were successfully resettled in Canada under the War Orphans Project.[3]

During the movement of Jewish war orphans to Canada, in the winter of 1948, Archbishop Charbonneau proposed a plan to help resettle 1,000 Catholic orphan children in Canada. In February 1948, representatives of the Catholic Church met with Hugh Keenleyside, Deputy Minister in the Department of Mines and Resources – the federal department responsible for the Immigration Branch. During their meeting, Keenleyside informed church representatives that in order to consider their proposal, the department required specific information including: a) the number of children; b) what method would be used to select the children; c) what method would be used to allocate the children to their new homes in Canada; d) which particular organ of the church would be responsible for placing and maintaining the children in Canada; and e) the necessary approvals from provincial welfare authorities in Ontario and Quebec.[4]

When it came to the selection of children overseas, church officials noted that they were in a “happy position of being able to secure the services of such persons” who would be qualified to effectively examine the physical and mental health of prospective children in order to guarantee that they would “make good Canadian citizens.” Church authorities also felt that given the difficulties in securing the required consent for legal adoption under Canadian law, legal guardianship would enable individuals, who were to care for the children, to take responsibility for their medical care and well-being.[5] The Catholic Immigrant Aid Society was tasked with filing an application for the admission of 1,000 orphan children, and coordinating their screening, selection, transportation, and resettlement to Canada.[6] On 3 August 1948, the Canadian government approved the resettlement scheme with the enactment of Order-in-Council P.C. 3396.[7]

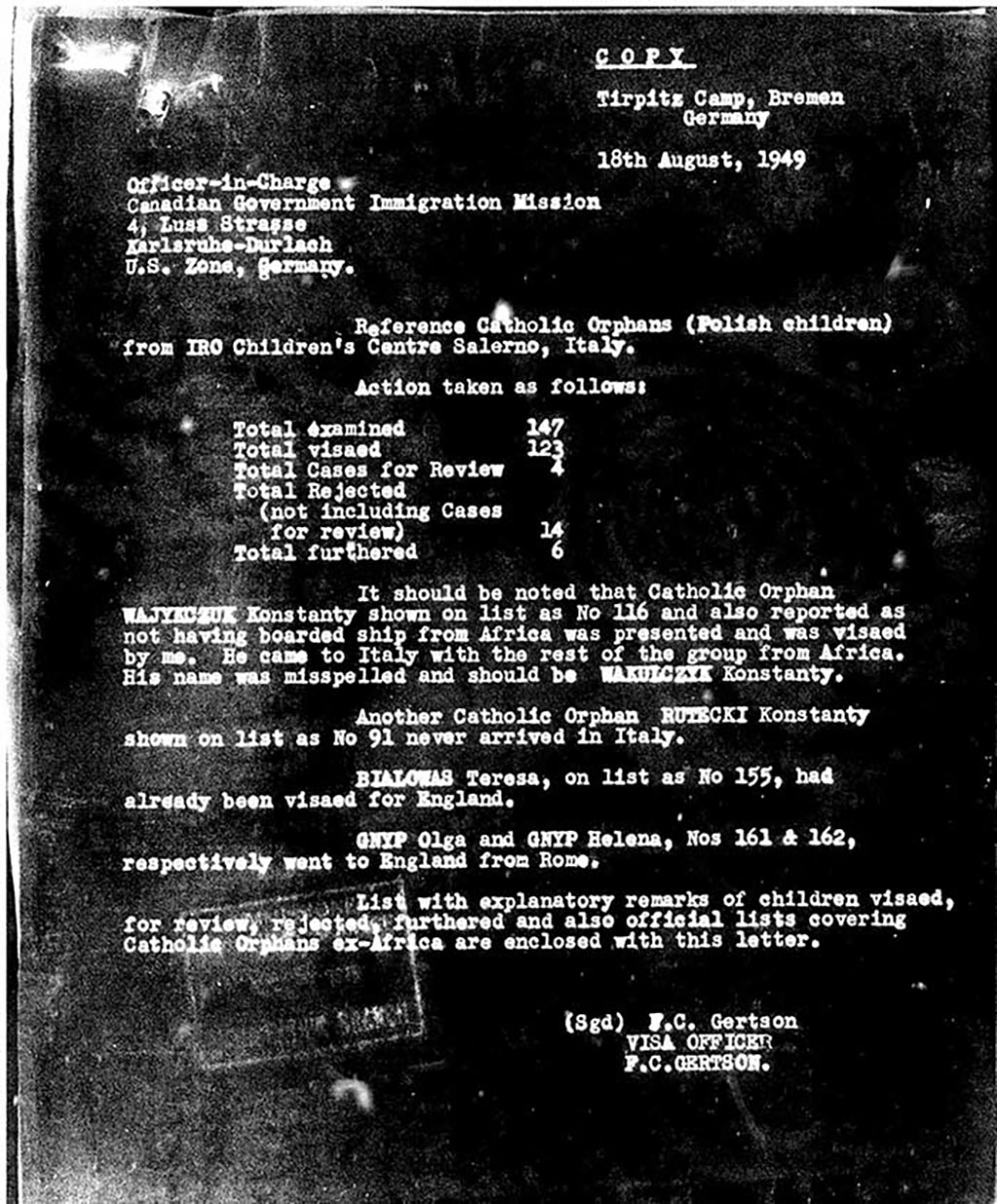

Canadian Officials Begin the Screening and Selection of Polish Orphans

In early 1949, Canadian officials began to consider the admission of an initial group of 79 Polish orphans from the Tengeru camp, but first sought to identify whether full medical examinations of the children would be possible. At the same time, Canadian diplomats were informed that another group of Polish orphans had arrived at Tengeru from refugee camps that had recently been closed in India, Northern Rhodesia, and Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). The list of prospective orphans seeking permanent resettlement provided to Canadian immigration officials now numbered 132. In March 1949, Canadian officials were informed that full medical screening was available at the camp, including X-ray examination of the chest and the Kahn blood test for syphilis.[8]

Canadian authorities soon learned of the International Refugee Organization’s (IRO) intention to move the Polish orphans to Italy by 1 May.[9] Without Canadian officials stationed in Tanganyika to administer medical screening, the Immigration Branch supported the IRO’s desire to move the children to Europe. In late June, the Polish orphans were successfully brought to the IRO Children’s Centre in Salerno, Italy.[10]

Cold War Politics: Communist Authorities and Catholic Officials

Cold War politics soon directly affected the movement of Polish orphans to Canada. Communist authorities in Poland had learned of their journey and sparked an international incident by publicly criticizing Canadian officials and the IRO for “kidnapping” the Polish orphans, rather than repatriating them back to their country of origin. Meanwhile, the Polish press depicted Canada as a “greedy capitalist nation” in need of children “as a source of cheap and exploitable labour.”[11] In an attempt to get the children back to their homeland, Polish communist representatives pursued the children from East Africa, to Italy and Germany, and eventually to Canada.[12]

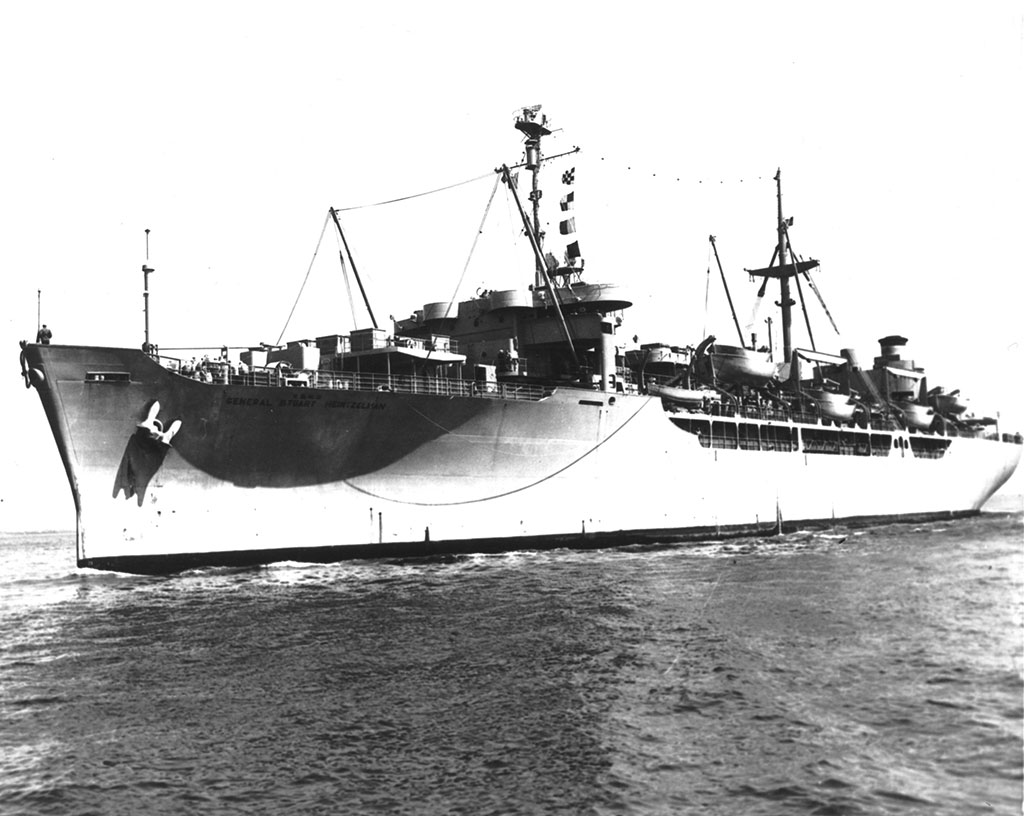

Under the auspices of the IRO, which had provided transportation to Canada, on 7 September 1949, USAT General Stuart Heintzelman docked at Pier 21 with some 300 DPs aboard ship, including 123 Polish Catholic orphans. Several weeks after their arrival, the orphans were followed by another smaller group of their compatriots. Upon reaching Pier 21, Father Lucjan Krolikowski, a Polish Catholic priest who had accompanied the children from East Africa, informed the gathered press that the Polish government’s accusation that the children had been kidnapped from Europe was false. Many of the older children added that they had voluntarily chosen to come to Canada despite communist claims to the contrary.

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (DI2013.146.1).

Credit: Library and Archives Canada, Immigration Branch Fonds, RG 76, vol. 660, file B74072 “Admission of Polish Orphan Children from Europe (lists),” microfilm reel C-10596.

Orphans at Pier 21

The Halifax Mail-Star reported that the orphans ranged in age from two to twenty. While the children under the age of ten “clamoured joyfully” around Pier 21’s immigration quarters, some of the older children remained quiet and feared to speak with the gathered press, who were interested in learning more about their journey. Eighteen-year-old Sofia Wakulczyk informed the press that after her parents had died in Siberia, she and her compatriots “…wanted to come to Canada, we do not want to go back to Poland.”[13] Meanwhile, a nineteen-year-old orphan, who wished to remain anonymous, indicated that “you don’t know what fear is until you’ve been in a Russian camp.” His parents had perished from typhoid while in Siberia, where he remembers being fed bread and hot water if he worked the whole day. When asked about what the young newcomer thought of Poland, he replied, “we like our country very much but it is not our country – now.”

New Arrivals Receive Safe Escort and Government Protection

Soon, another cause for concern arose for the children and their chaperones. A small group of Polish communists had awaited the arrival of the children at Halifax. As Catholic officials oversaw the orphans’ resettlement in Canada, they were quickly processed through immigration and customs. With the help of several Catholic priests and nuns including representatives of the Catholic Immigrant Aid Society, the orphans were safely escorted past the “Soviet Poles” before boarding a train destined for Montreal. Proponents of the Warsaw government unsuccessfully followed the children to Catholic summer camps near Drummondville, Quebec, where they were temporarily housed before reaching their final destinations. A small number of the orphans had remained on the train and arrived in Montreal to find Polish communists waiting with sweets. Once again, the children were protected by Catholic representatives before eventually being placed in day and boarding schools, while their older compatriots attended university or found employment in industry or as domestic servants.

For its part, the Canadian government refused to surrender the orphans to Polish officials. Once it became clear to the communist authorities that the children would not be returned to Poland, they abandoned their efforts. With the help of the Catholic Church and the Polish community in Canada, the orphans turned their attention towards becoming Canadians.[14]

Conclusion

In 1949, the initial movement of 123 orphans, followed by another smaller group several weeks later, formed only a small contingent of the 19,184 Polish-born individuals who entered Canada that year.[15] Many arrived under the Canadian government’s Displaced Persons movement, between 1947 and 1952, which brought over 186,000 individuals to Canada. While much has been written about the postwar resettlement of DPs as contract labourers in the agricultural, industrial, mining, forestry, and domestic service sectors, the admission and resettlement of displaced minors remains understudied and deserves further examination.

- Jan T. Gross, “Sovietisation of Poland’s Eastern Territories,” in From Peace to War: Germany, Soviet Russia, and the World, 1939-1941, edited by Bernd Wegner, 63-78 (Providence: Berghahn Books, 1997), 77-78; Halik Kochanski, The Eagle Unbowed: Poland and the Poles in the Second World War (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012), 163-173; “120 000 People,” Anders Army, http://www.andersarmy.com.↩

- Lynne Taylor, Polish Orphans of Tengeru: The Dramatic Story of Their Long Journey to Canada, 1941-1949 (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2009), 9-10.↩

- Gerald E. Dirks, Canada’s Refugee Policy: Indifference or Opportunism? (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1977), 167; Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, “Welcome to Canada,” Open Hearts, Closed Doors, http://www.virtualmuseum.ca/sgc-cms/expositions-exhibitions/orphelins-orphans/english/themes/welcome/page1.html.↩

- Library and Archives Canada (hereafter LAC), Immigrant Branch (hereafter IB) fonds, RG 76, vol. 660, file B74072 “Admission of Polish Orphan Children from Europe (lists),” H.L. Keenleyside, Deputy Minister, Department of Mines and Resources to A.L. Jolliffe, Director, Immigration Branch, Department of Mines and Resources, Ottawa, 11 February 1948.↩

- Permanent Secretariate of the Canadian Episcopate, “Immigration to Canada of Unaccompanied Orphan Children from Europe,” n.d.↩

- Memo for file, A.L. Jolliffe, Director, Ottawa, 3 May 1948.↩

- W.R. Baskerville, Supervisor, Juvenile Immigration, for Acting Commissioner, Immigration Branch, Department of Mines and Resources, Ottawa, 16 September 1948.↩

- A.L. Pennington for Acting Chief Secretary to Acting Under-Secretary of State for External Affairs, Ottawa, 26 March 1949.↩

- Laval Fortier, Associate Commissioner, Overseas Service, Immigration Branch, Department of Mines and Resources to Monsignor J.-L. Beaudoin, French-Speaking Secretary of the Episcopate, Permanent Secretariate of the Canadian Episcopate, Ottawa, 9 April 1949.↩

- Laval Fortier to Monsignor J.-L. Beaudoin, Ottawa, 13 April 1949; Taylor, Polish Orphans of Tengeru, 178.↩

- Monika Katarzyna Payseur, “‘I don’t want to go back’”: The Complicated Case of Polish Displaced Children to Canada in 1949,” (M.A. thesis, Ryerson University, 2009), 20.↩

- Taylor, Polish Orphans of Tengeru, 9-10.↩

- Jack Regan, “‘Kidnapped’ Polish War Orphans Reach Halifax,’” Halifax Mail-Star (8 September 1949): 1, 6. In the article, Wakulczyk was improperly identified as “Wakillcyk.” See Taylor, Polish Orphans, 275.↩

- Regan, “‘Kidnapped’ Polish War Orphans Reach Halifax,’” 1, 6; Taylor, Polish Orphans of Tengeru, 9-10, 223-224, 237-239.↩

- Canada, Department of Trade and Commerce, Dominion Bureau of Statistics, The Canada Year Book 1952-53 (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer and Controller of Stationery, 1953), 169.↩