by Steve Schwinghamer, Historian

(Updated July 20, 2021)

“There is no Exclusion Act in the Dominion of Canada”

“The doors which once were opened wide are now but slightly ajar. The countries that boasted of their liberal attitudes toward new settlers – particularly the countries of the Western Hemisphere – are much more strict in their requirements today in permitting a foreigner to enter their boundaries for permanent settlement.”

– Harold Fields, The American Journal of International Law, 1932.[1]

Introduction: The Great Depression and Canadian Nativism

In the 1930s, Canadians experienced a profound economic recession complicated by drought and the collapse of trade: the Great Depression. Since many immigrants came to Canada as farmers or labourers, they were particularly vulnerable during the economic downturn. Further, Canadian public debate at the time often included a strong element of nativism, as expressed by Rev. W.B. Williston of Cochrane, Ontario:

“The public rightly ask, that you remove from this place, the Russian and other European people, who have only been in this country for a short time, and particularly the men of this class who are sending all their earnings back to Europe, should not be allowed to have the work on the Power and R.R. construction, while hundreds of Canadians are standing in the bread line.”[2]

Sentiments like Rev. Williston’s were widespread in Canada during the early 1930s, when about one-quarter of the Canadian labour force was unemployed.[3] This created tremendous pressure on governments to respond to the dire labour conditions with exclusionary immigration policies.

Severe Immigration Policies

In 1930-31, the Canadian government responded to the Great Depression by applying severe restrictions to entry. New rules limited immigration to British and American subjects or agriculturalists with money, certain classes of workers, and immediate family of Canadian residents. The result was dramatic. In the 1930s, an average of about 16,000 immigrants entered Canada per year, an enormous drop from an average of about 126,000 per year during the 1920s.[4] Clifford Sifton, one of the architects of the turn-of-the-century boom in immigration to Canada, stated in 1899 that “there is no Exclusion Act in the Dominion of Canada” and that “it is no part of the duty of the Government…to appoint agents for the purpose of keeping people from coming to Canada.”[5] Thirty years later, the policies of Canadian immigration shifted to perform exactly that function.

With screening abroad and at the border tightened, the immigration branch intensified its work in another area of exclusionary immigration practice: deportation. This had been developing for some time. After restrictive amendments to the Immigration Act passed in 1919, Secretary of Immigration F.C. Blair asked the Minister of Immigration and Colonization to sign blank deportation orders in bulk. By way of reassurance, Blair stated that he was “convinced that this would not open the door to any abuse.”[6] Following these changes in policy and practice, the deportation rate during the Great Depression spiked to about six times prior rates, and about 25,000 immigrants were sent out of Canada. Although unemployed workers were key targets, illness, ideology, or perceived immorality were also grounds for deportation.

Poverty and Exclusion

Poverty was one of the main reasons a person might be excluded by Canadian immigration authorities. It was addressed in all the historical immigration acts and was particularly relevant during the hard times of the Great Depression. The 1869 Immigration Act singled out pauper immigrants, making ships’ masters responsible for their maintenance and transportation to their destination in Canada. The 1906 Immigration Act developed this further, prohibiting any immigrant “who is a pauper, or destitute, a professional beggar, or vagrant, or who is likely to become a public charge,” as well as those who became “a charge upon the public funds…or an inmate of or a charge upon any charitable institution” after arrival.[7] Despite these regulations, the commissioner of immigration wrote in 1930 that “…where the complaint in regard to a single man bears no reference to any physical or other disabilities and the extent of relief is negligible, the Department does not propose to issue a Minister’s Order unless there is additional material submitted in support”.[8]

Credit: Library and Archives Canada, PA-034947

This tolerant approach weakened as the burden of public charges related to unemployment escalated. In her study of deportation, historian Barbara Roberts pointed to the example of Winnipeg, where the cost of public relief amounted to just over $31,000 in 1927-28. In 1930-31, the same cost was more than fifty times higher, at over $1.6 million.[9] This led to many petitions from cities and charities, requesting that the federal department of immigration take responsibility for—and deport—immigrants in a variety of situations. One petition dealt with a woman living with mental illness, despite both her and her parents being permanent residents in Canada; another, the return of young boys brought to Canada to failing farms.[10] One city relief officer from Toronto went to the press and recorded his complaint that “about 50 per cent of the people whom I report to the immigration authorities should never have been admitted” under the headline, “Many Undesirables Admitted to Canada.”[11] The immigration department explained its position to the public by arguing that it acted “at the instance of the provincial authorities” and asserted that “Canada is not deporting immigrants because they are unemployed but mainly because they were unemployable.”[12]

Deportation and Unsuitability

The divisions in public opinion on deportation are evident in a letter Rev. Canon C.W. Vernon, an Anglican minister active in social services, wrote to W.J. Egan, the deputy minister of immigration, in 1930:

“I have seen the reports in the newspapers from a number of western cities of the movement to deport all who have been in Canada for less than five years and are now applying for relief. I have also noted with pleasure that the Minister and the Department apparently fully realize the undesirability, to put it mildly, of such wholesale deportations.

I believe that the present economic distress and consequent slowing up of migration work should be used as giving the Department an opportunity gradually and quietly to arrange for the deportation of all recent arrivals, who have at once proved themselves physically, mentally or morally unsuitable for settlement in Canada.”[13]

That unsuitability took several forms. Immigrants in jail had convictions that could be used to support deportation apart from their costs to the public purse. The immigration department also pursued immigrants staying in hospitals at public expense. Repeated directions to both immigration and deportation officers, as well as to hospital and other institutional authorities, underscore an atmosphere of confusion that surrounded the deportation of the unwell.[14] A 1931 letter warning that “the wrong person has been delivered to the Deportation Officer by the hospital” indicated the difficulties in transferring the care of an immigrant between authorities.[15] Departmental reports indicate that medical grounds accounted for about ten percent of deportations, but this may be a low estimate. Immigrants who incurred public expense for hospital stays were often listed deported for being a public charge rather than for medical reasons.[16] Whether they were accounted unsuitable due to criminality, ill-health, or poverty, the resulting process was the same.

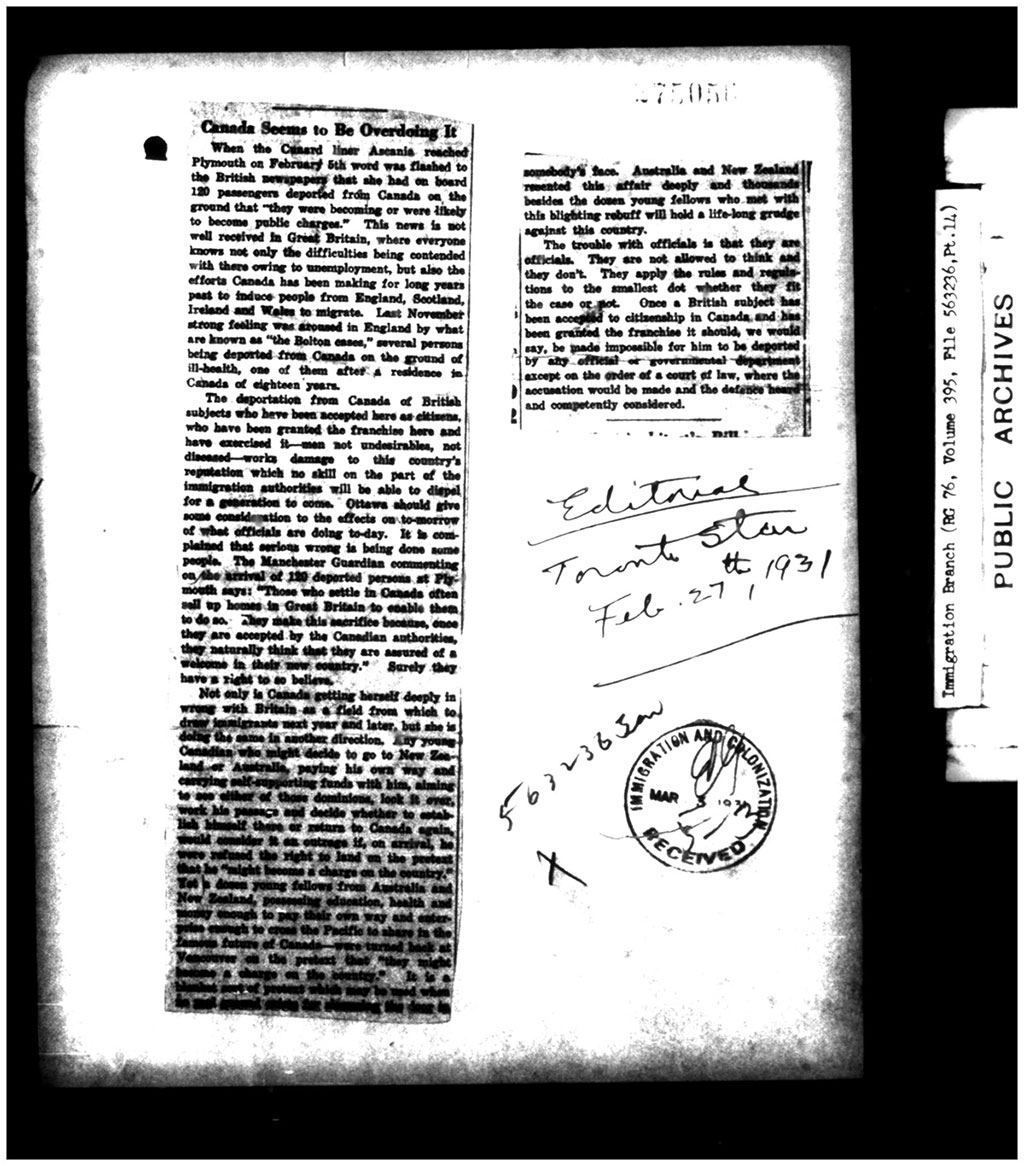

Credit: Editorial, Toronto Star, 27 February 1931 (copied in “Deportation of undesirables from Canada (lists)”, Library and Archives Canada, RG 76 Volume 395 File 563236 Part 14)

Conclusion: Massive Deportation

As observed by the Toronto Star on November 1, 1930, deportation seemed “to be a rather flourishing business for the ocean boats and the Canadian railways, bringing out ten thousand persons per year and taking them back again.”[17] This is an overstatement, but the total deportation in this period is sizeable: for every two or three people admitted to Canada, one was being deported. The pace of deportation was such that in 1931, the immigration quarters in Montreal were over capacity, filled with people being sent back to their countries of origin. In Halifax, Pier 21’s detention facilities were also overwhelmed at times, and the local Royal Canadian Mounted Police barracks had to be used. Foreign governments took note of the outflow. For instance, the Consul General of the Netherlands sought information on each deported person bound from Canada to the Netherlands, regardless of nationality. Even the steamship lines began to complain about the administrative burden, requesting that immigration agents make up an additional copy of the case history so that they could process deportations promptly instead of being delayed by having to duplicate parts of the file.[18]

Canadian authorities responded to the Great Depression in part by a strong use of exclusionary immigration policies. The massive drop in immigrant arrivals due to new screening abroad and at the border complemented intense efforts to deport immigrants deemed unsuitable. The practice and policy of immigration in Canada during the 1930s put into effect the “exclusion act” that Sifton had previously dismissed.

- Harold Fields, “Closing Immigration Throughout The World”, The American Journal of International Law, 26:4 (October 1932), 671.↩

- W.B. Williston to G. Robertson, Cochrane, 14 July 1931, in Department of Immigration, “Deportation of undesirables from Canada (lists)”, Library and Archives Canada RG 76 Volume 395 File 563236 (hereafter File 563234) Pt 14.↩

- Valerie Knowles, Strangers at Our Gates: Canadian Immigration and Immigration Policy, 1540-1997 (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1997), 115.↩

- Lindsay Van Dyk, “Order-in-Council PC 1931-695”, web log entry, accessed at http://www.pier21.ca/research/immigration-history/order-in-council-pc-1931-695-1931 on 16 December 2014; Dominion Bureau of Statistics, The Canada Year Book, 1945 (Ottawa: Edmond Cloutier, 1945), 168; Dominion Bureau of Statistics, The Canada Year Book, 1946 (Ottawa: Edmond Cloutier, 1946), 185.↩

- House of Commons Debates, 26 July 1899, 8567-88, quoted Ninette Kelley and Michael Trebilcock, The Making of the Mosaic: A History of Canadian Immigration Policy (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000, 121.↩

- F.C. Blair to Calder, Ottawa, 6 December 1920, File 563236 Pt 8.↩

- Canada. Immigration Act, 1906, Section 28. Accessed at http://www.pier21.ca/research/immigration-history/immigration-act-1906 on 16 December 2014.↩

- A.L. Jolliffe to T. Gelley, Ottawa, 27 May 1930, File 563236 Pt 14.↩

- Barbara Roberts, Whence They Came: Deportation from Canada, 1900-1935 (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1988), 162.↩

- Jolliffe to Fraser (on behalf of Brantford), Ottawa, 9 October 1930, 563236 Pt 14; G. Clare to W. Egan, Quebec City, 11 October 1930, File 563236 Pt 14.↩

- Unknown. “Many Undesirables Admitted to Canada: Relief Officer Would Like to Know How Some Got In”, Toronto Star, 4 November 1930.↩

- Unknown. “Protest Impends in British House Over Deportations”, Montreal Star, 29 October 1930, 1; unknown, “Deportations from Canada”, Manitoba Free Press (Winnipeg ), 12 February 1931.↩

- C.W. Vernon to W.J. Egan, Toronto, 3 December 1930, File 563236 Pt 14↩

- See, for instance, Jolliffe to Gelley, 1 May 1931, File 563236 Pt 14, for comments on both the prevalence of errors and attempts to address the problems through process.↩

- A.L. Jolliffe to A.E. Skinner, 26 August 1931, File 563236 Pt 14.↩

- Roberts, Whence They Came, 46; continuing correspondence in File 563236.↩

- Unknown. “Those Deportations”, Toronto Star, 1 November 1930↩

- Kelley and Trebilcock, Making the Mosaic, 217, 227; J.S. Fraser to J.M Langlais, Ottawa, 18 August 1931, File 563236 Pt 14; Roberts, Whence They Came, 129; J.A. Schuuman to O.D. Skelton, 8 January 1931, File 563236 Pt 14; A.R. Hughes to A.L. Jolliffe, 13 February 1931, File 563236 Pt 14.↩