by Jan Raska, PhD, Historian

(Updated November 4, 2020)

Origins: From a “Mosaic” to Multiculturalism

Before multiculturalism became a widely-used metaphor for cultural pluralism in modern Canada, the use of such terms to describe Canadian diversity can be traced back to the early interwar period. Against the backdrop of a Canadian state that had formulated a specific construction of Victorian and British identity as a project of rule, tens of thousands of non-British immigrants arrived in Western Canada in the early twentieth century. The term ‘mosaic’ was first used by American travel writer Victoria Hayward in 1922, to describe this cultural change across Canada. In her book, Romantic Canada, Hayward referenced Canada’s European characteristics, but also pointed to the country’s Indigenous and Asian communities who she described as part of a Canadian “mosaic.”[1] In 1926, writer Kate Foster published an overview of Canadian immigration for the Dominion Council of the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) entitled, Our Canadian Mosaic. In her work, Foster described the contributions of seventeen European and Asian immigrant groups to Canada, but her focus on social order suggests a preference for the Anglo-conformity of diverse ethnocultural groups across the country.[2]

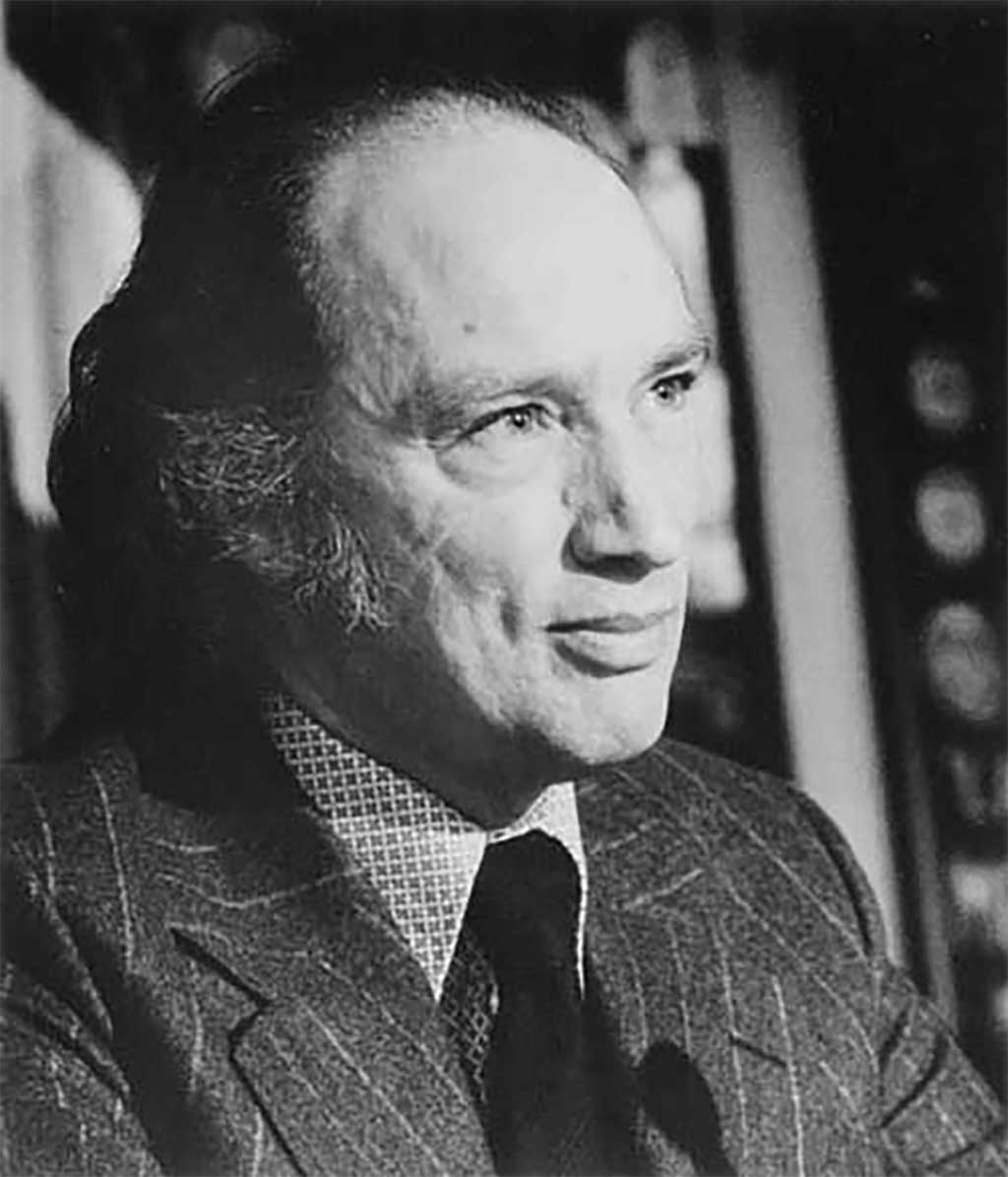

The term ‘mosaic’ was later popularized by writer, cultural promoter, and General Publicity Agent for the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), John Murray Gibbon, who is credited with linking the mosaic with a multicultural Canada. Between 1928 and 1931, under the auspices of the CPR, Gibbon arranged a series of sixteen “folk festivals” of song, dance, and handicrafts across the country.[3] In 1938, Gibbon published Canadian Mosaic: The Making of a Northern Nation, in which he profiled diverse European “racial groups” in Canada and how they retained their ethnocultural identities, including language, customs, food, and dress. However, Indigenous peoples, Asian immigrants, and persons of African descent were omitted from his overview.[4]

While ethnic identity and the ‘mosaic’ became linked, early discussions about race and multiculturalism were limited in large part due to the existence of systemic racism in Canada. In 1936, Jamaican immigrant Fred Christie sued a Montreal tavern for refusing to serve him because of its house policy to not serve “Negroes.” In Christie v York (1939), the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that private establishments were allowed to discriminate on the basis of free enterprise. With this, Canada’s legal system had confirmed that ideas of racial inferiority were entrenched in interwar Canada.[5]

The promotion of cultural pluralism, while avoiding any mention of race or systemic racism in Canada, also extended to the political sphere when Governor General John Buchan (Lord Tweedsmuir), who served from 1935 to 1940, “encouraged Canadians to make multiculturalism a defining feature of Canadian identity and nationalism.”[6]

The notion of Canada as a cultural ‘mosaic’ (or multicultural) existed alongside systemic racism, which excluded Canadians of non-European backgrounds, and was contrasted later with the metaphor of a ‘melting pot’ (or cultural assimilation) in the United States, which brought different groups together to form a monoculture that exhibited the characteristics of the many.[7]

Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism

By the early 1960s, multiculturalism was a source of national debate between proponents of biculturalism, who viewed Canada as culturally and linguistically of British and French origin, and promoters of multiculturalism, many of whom represented non-British and non-French ethnocultural communities in Canada, who suggested that Canadian identity was not simply bi-national, but culturally pluralistic or multicultural. These debates illustrated enduring tensions such as in Quebec, where proponents of francophone nationalism called on the federal government to protect the French language and culture, and for francophone Quebecers to participate more fully in the country’s political and economic decision-making. To address these concerns, the federal government established the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism.[8]

From 1963 to 1969, the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism (commonly referred to as the Bi-Bi Commission) examined the extent of bilingualism in the federal government, how governmental and non-governmental organizations promoted cultural relations, and the level of opportunities for Canadians to become bilingual in English and French in the hopes of establishing greater equality between English and French Canada. The Bi-Bi Commission was chaired by Davidson Dunton, a public servant, educator, and president of Carleton University, and André Laurendeau, a journalist, politician, playwright, and publisher of Montreal’s French-language daily, Le Devoir. The commissioners were instructed to also explore the cultural contributions of other ethnocultural groups in Canada. Soon after the Bi-Bi Commission’s launch, ethnocultural groups across Canada expressed concern that their cultural contributions were being ignored. At the time of the Bi-Bi Commission, approximately 26 percent of Canada’s population was neither British nor French in ethnic origin.[9] Published in 1969, Book Four (The Cultural Contribution of the Other Ethnic Groups) of the Bi-Bi Commission’s official report attempted to address this reality and the concerns of Canada’s ethnocultural communities.[10]

Responding to the Bi-Bi Commission: Federal Cabinet Considers a Multiculturalism Policy

In September 1971, the federal Cabinet met to discuss a report completed by its Cabinet Committee on Science, Culture and Information. The committee examined a joint memorandum from the Secretary of State, Gérard Pelletier, and the Minister without Portfolio (Citizenship), Martin O’Connell, seeking approval for a policy of multiculturalism in response to the recommendations found in Book Four of the Bi-Bi Commission’s official report. Although the committee approved the proposed multicultural policy, it believed the policy’s implications for national sovereignty and national unity were significant, and therefore brought the proposed policy before the full Cabinet for consideration.

During discussions, several Cabinet ministers stressed that a future multiculturalism policy had to “be set firmly within [a] Canadian context.”[11] Minister O’Connell reassured his colleagues that the proposed policy would indeed be placed in a proper context. The Minister of Justice, John Turner, suggested that official multiculturalism would make a definite contribution to national unity. According to Turner, the policy would counteract the view, particularly in Western Canada, that the federal government “had shown an excessive concern for the problems of other cultural groups in Canada.”[12] Meanwhile, Prime Minister Trudeau pondered how ethnocultural communities, who were dismayed by the final recommendations of the Bi-Bi Commission, would receive the policy. The ensuing discussion centered on how many ethnocultural groups believed there was an implicit bias towards biculturalism (i.e. “cultural absorption” of ethnocultural groups into either English or French culture) in the Royal Commission’s findings. Cabinet members concluded that some “militant” ethnocultural leaders would argue that the multiculturalism policy did not go far enough, but that a majority of ethnic Canadians would find the new policy acceptable.

Cabinet discussions soon turned towards the funding of third (ethnic) language maintenance and ethnocultural projects. Cabinet members were aware that in Western Canada, ethnocultural groups such as the Ukrainians had called for their languages to be given the same status as English and French. However, some ministers felt that since young members of these communities seemed to be more interested in learning English or French than in “fighting for official status for their ethnic tongue,” pressures for third languages to be given official status would soon diminish. These same ministers then argued that providing assistance for third languages would “help preserve the ethnic cultures and also to help more Canadians to master languages other than English and French, something which was obviously desirable in today’s world.”[13]

Prime Minister Trudeau noted that the proposed official multiculturalism policy could raise expectations on the part of the Canadian public of the amount of funds that the federal government would offer to ethnocultural groups across the country. It was Trudeau’s hope that the policy would promote “self-help” by ethnocultural groups and that funding programs for third language maintenance and ethnocultural projects would be planned and implemented carefully. Further to his point, Trudeau concluded that the multiculturalism policy should not give Canadians the impression that it would achieve economic equality for all ethnocultural groups. Rather, the proposed policy would promote cultural equality for all Canadians.

Meanwhile, the Minister of Transport, Don Jamieson, worried that the policy might give the Canadian public the impression that the federal government favoured licensing third language radio and television stations; therefore, he advised his Cabinet colleagues that the Canadian Radio-Television Commission (now the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission) could study the possibility. Jamieson then indicated that he was not against English- and French-language stations providing additional airtime for third language programming.

With the multiculturalism policy favourable to the federal Cabinet, its announcement coincided with the distribution of letters from the Prime Minister to the provincial premiers, informing them of this new policy.[14] Under the Canadian Constitution, the federal government shares certain powers with the provinces, such as immigration. The provinces also hold their own powers which include education, health, social services, and civil rights. For the future implementation of the official multiculturalism policy, the federal government required the cooperation of the provinces.[15]

Announcing an Official Multiculturalism Policy

In October 1971, Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau stood before the House of Commons and announced his government’s implementation of a policy of multiculturalism within a bilingual framework. The policy resulted from the federal government’s acceptance of all the recommendations put forward in Book Four of the Bi-Bi Commission’s official report. According to Trudeau, Book Four explored the question of cultural and ethnic pluralism in Canada and the status of various cultures and languages, a subject that was understudied by scholars.[16] The official multiculturalism policy consisted of four elements:

- Encouragement and support for all of Canada’s cultural groups who aspired to survive and continue to develop, and in clear need of assistance;

- Overcoming existing barriers (ex. sense of belonging, inferiority) to full sociocultural citizenship in Canada;

- Promotion of creative intercultural exchanges between cultures in Canada to strengthen national unity;

- Providing further support for immigrants to learn one of Canada’s official languages.[17]

As a means to provide financial support for Canada’s cultural groups, the federal government allocated nearly $200 million over the next ten years following the implementation of the official multiculturalism policy. In 1972, a Multiculturalism Directorate was established within the Department of the Secretary of State to provide assistance in implementing the policy and its programs. The federal government sponsored activities aimed at providing assistance to ethnocultural minorities including immigration, citizenship, elimination of discrimination, and the promotion of human rights. A year later, a Ministry of Multiculturalism was established to oversee the implementation of multicultural policies in government departments. Outside of the federal bureaucracy, Canadian officials established formal partnerships with ethnocultural organizations such as the Canadian Consultative Council on Multiculturalism, founded in 1973 (now the Canadian Ethnocultural Council).

Initially, federal officials responsible for multicultural policy initiatives viewed any barriers to sociocultural citizenship and economic success in cultural or linguistic terms. The liberalization of Canadian immigration policy and removal of the last vestiges of geographic and ethnoracial discrimination in the late 1960s saw an increase in the arrival of visible minority immigrants. These same officials soon realized that their efforts needed to be focused on combatting and eliminating racial discrimination.[18]

The House of Commons Responds to an Official Multiculturalism Policy

Before the House of Commons on 8 October 1971, Trudeau indicated that his government agreed with the Bi-Bi Commission’s assertion that individuals were less influenced by their origins or mother tongue, but rather by their own “sense of belonging to the group… [and its] …‘collective will to exist,’” and supported its recommendations that “…there cannot be one cultural policy for Canadians of British and French origin, another for original peoples and yet a third for all others. For although there are two official languages, there is no official culture, nor does any ethnic group take precedence over any other. No citizen or group of citizens is other than Canadian, and all should be treated fairly.”[19] If the official multiculturalism policy was meant to protect an individual’s ethnocultural identity, its purpose was also intended to protect an individual’s freedom from being “locked for life” within a particular ethnic, cultural, or linguistic identity by providing them with an opportunity to learn one of two official languages. Trudeau concluded that the policy was “…the most suitable means of assuring the cultural freedom of Canadians.”[20]

In his response to Trudeau’s declaration, the Leader of the Official Opposition, Robert Stanfield, who supported the policy, noted that it was about time that the federal government admitted that “…the cultural identity of Canada is a pretty complex thing” and it was time for federal officials to help preserve and enhance the diverse cultural traditions found across Canada. Stanfield was quick to qualify his support of the policy by suggesting that the promotion of official multiculturalism “in no way constitutes an attack on the basic duality of our country. What we want is justice for all Canadians, and recognition of the cultural diversity of this country.”[21]

Leader of the Commonwealth Co-Operative Federation, David Lewis, expressed his party’s support and hopes for the policy and indicated that the House of Commons was “united in its belated determination to recognize the value of the many cultures in our country.” Lewis went on to suggest that part of Canada’s wealth was its establishment by “two distinctive groups having two distinctive languages” and the cultural diversity found across the country.[22] According to Lewis, the past failure in implementing a multiculturalism policy was “not the fault of any one government” in Canada, but a failure on the part of all Canadians to “appreciate the importance of these things” and in their neglect of Indigenous peoples in Canada.[23]

Leader of the Social Credit Party, Réal Caouette, supported Trudeau’s announcement stating that he believed too in a Canada with two official languages and one Canadian nation with a “multiplicity of cultures which are the wealth of our country.” Despite his support, Caouette remained confused by Trudeau’s statement indicating that Canada had no official culture. Caouette replied that he believed Canada could not become a successful nation without one culture: “…we would be endowed with only a few cultures unable to get on among themselves or at war with one another. I am positive that we have in Canada a culture peculiar to us.” The Social Credit leader argued that as English and French Canada had cultures that were separate from those of England and France, so too did Canada have its own culture with its own history. Caouette concluded that ethnic identities could not be changed (“an Englishman into a Frenchman, or vice versa”), but that all individuals no matter their ethnic background could be made into “good Canadians.”[24]

Given the parliamentarians’ views of the 1971 official multiculturalism policy and contemporary multiculturalism in Canada, what did the Canadian public think of the nascent policy of official multiculturalism in the early 1970s? What were their responses?

Early Public Responses to Official Multiculturalism

In the first twelve months after the announcement of an official multiculturalism policy, media coverage in Canada’s major English- and French-language dailies varied from descriptive news reporting and interviews with policymakers, to editorials, and letters to the editor from the Canadian public. The latter consisted of letters from ordinary Canadians and ethnocultural community leaders, and elected officials. The issues presented ranged from national unity, Indigenous and ethnocultural representation in politics, the values of multiculturalism versus the (American) melting pot, and the place of ethnocultural identity in Canada. In most cases, the published responses did not mention race or racism in Canada when discussing multiculturalism.

Rather, several days after Trudeau’s announcement of an official multicultural policy, Le Devoir published an opinion piece by Serge Losique, founder of Montreal’s Conservatory of Cinematographic Art. Under the headline, “Le mythe dangereux de multiculturalisme,” Losique indicated that each citizen had the right and duty to question the decisions of their political representatives. He believed that the new policy would delay the edification of a Canadian cultural identity and possibly cause internal divisions in each province. Losique argued that in order to encourage an ethnocultural group to create and maintain its own culture, the federal government would need to establish separate schools for all ethnic minorities in Canada, positions in radio and television in order to convey culture, guarantee subsidies for ethnocultural literature and media, and to create official organizations to ensure permanent cooperation with an ethnocultural group’s country of origin. Losique believed these conditions were the minimum required to assure an ethnic minority’s cultural survival. Losique was also concerned that the multiculturalism policy did a disservice to immigrants and their children because it risked keeping them in “ghettos” and making them into marginalized citizens. Losique argued that Canada’s essential problem was that it was still searching for its Canadian culture. He concluded that before Canadians veered towards a “grandiose policy” of multiculturalism, they needed to understand that the “French cultural fact” across Canada was still under threat. He wondered whether Canada should focus first on its English and French cultures and their economic progress.[25]

In response to an editorial by Claude Ryan, publisher of Le Devoir, in which he questioned whether the assistance provided to ethnocultural groups (through the multiculturalism policy) would demand an abandonment of biculturalism, historian (and future professor of Canadian political history at the University of Ottawa) Michael Behiels countered this suggestion by arguing that what was actually in doubt was the ability of Canada’s citizens of diverse backgrounds to integrate without having to deny their cultural heritage. Behiels went on further to suggest that a multicultural policy was not a policy to assimilate ethnocultural groups, but rather one of integration. The multiculturalism policy was an also expression of Canada’s reality as a multicultural society.

While Ryan opposed a multicultural policy within a bilingual framework because it did not recognize any official Canadian culture, Behiels quoted Trudeau who refused to subscribe to the notion that “two nations” were implicitly linked to official language policy in Canada, but instead declared that “languages have two functions. They act both as a vehicle of communication and as a preservation of culture. Governments can support languages in either or both of these roles, but it is only in the communication role that the term ‘official’ is employed. An overwhelming number of Canadians use English or French in their day to day communication with one another and with governments.” Behiels supported the federal government’s “pluralistic policy” because he believed that a biculturalism policy would lead to “special status” for French Canadian culture (or English Canadian culture) to the detriment of other minority cultures in Canada. Behiels concluded that since the federal government recognized the aspirations of Canada’s other cultures, these groups were more likely to recognize multiculturalism under a bilingual framework.[26]

In the months that followed, some letters to Le Devoir described multiculturalism as a myth and political stunt. Professor Albert Deloras-Billot of Rouyn, Quebec, declared that if Canadians wanted to maintain a multiplicity of cultures, then they would need to also recognize a multiplicity of official languages. Fernand Dumont, a prominent Quebec sociologist and professor at Université Laval, poked fun at Trudeau’s announcement of an official multiculturalism policy and the federal government’s lack of understanding of certain terms: identity, culture, nation, and allegiance.

Many ordinary citizens weighed in too. For example, Montreal resident Claude Jasmin asserted that the multiculturalism policy was evidently a manoeuvre to divert citizens away from the current political climate of polarisation. Rather than affirming biculturalism, the federal government was attempting to collect votes from diverse ethnic communities. Louis Landry, a resident of Repentigny, Quebec, argued that ethnic cultures found in North America – created and adapted by human interactions elsewhere – had to also adapt to the needs of Canadian and American societies. Landry believed that many of the cultural aspects that had been maintained in North America were unnecessary elements of culture best described as folkore. Landry claimed that proponents of biculturalism or multiculturalism were in fact practicing “bi-folklorisme” and “multi-folklorisme.”[27] While Landry did not define culture, he could have mentioned the different layers of cultural meaning, both visible and non-visible, through relationships, ideals, attitudes, practices, etc., and whether the federal government had provided the necessary space for broader expressions of culture.

Issues of Mutual Concern: Ethnocultural Representatives Address Official Multiculturalism

In late April 1972, the Toronto Star published a full page spread titled “Ontario’s Cultural Mosaic” which described the provincial government’s upcoming multiculturalism congress to be held in Toronto, in early June 1972. The conference, Heritage Ontario, was later attended by over 1,000 individuals from 54 cultural groups. The newspaper featured interviews with five individuals of diverse backgrounds (Indigenous, French, English, Portuguese, and Ukrainian) who spoke about their views of official multiculturalism. The Toronto Star featured only a limited cross-section of Canadian society, focusing on individuals who cautiously or outright supported official multiculturalism over those who might vehemently oppose such a policy. As such, the paper found its interviewees to be generally in favour of the federal government’s policy of “varied cultures maintaining their individual traditions [which] is indefinitely preferable to the melting pot system as demonstrated by the United States.”[28]

Portuguese Canadian law clerk Fernando Dias Costa hoped the upcoming conference would be more than “another exercise in public relations.” According to Costa, the Portuguese were the latest significant immigrant group to arrive in Ontario, and more notably, Toronto, and had struggled to acquire English-language proficiency. Costa believed that children should be taught their own language first before learning an official language. He went on to suggest that the Portuguese in Toronto were deprived of socioeconomic advancement and their goals were limited due to a lack of funding and access to professional programs compared with other ethnocultural groups. According to Costa, many Portuguese immigrants were unskilled labourers and required social assistance after arriving in Canada. Costa concluded his remarks by suggesting that Portuguese representatives would attend Heritage Ontario with suspicion as “for a long, long time two languages have been supreme. Suddenly the federal government has allocated millions for multicultural projects and the provincial government is full of ideas. We will judge on what is implemented.”[29]

Gloria Ochitwa, a member of the national executive of the Ukrainian Women’s Association of Canada, considered herself a Canadian and resented being categorized as a hyphenated Canadian (i.e. Ukrainian-Canadian). As a third-generation Canadian, Ochitwa argued that everyone was part of an ethnocultural group and saw no contradiction between her Canadian identity and the maintenance of Ukrainian customs and heritage, including blending old and new traditions. She wondered whether official multiculturalism would force “people of Ukrainian origin to become Anglicized?” Ochitwa concluded her remarks by claiming that some ethnocultural prejudices remained “even though we like to gloss things over.” Ochitwa pointed to the lack of non-English and non-French names found at the highest levels of business and on the boards of universities and hospitals. According to her, Canada had a “vertical mosaic with the Anglo-Saxon group at the top.”[30]

Hamilton lawyer Ryan Paquette, who served as president of the French-Canadian Association of Ontario, asserted: “We have not got everything we have asked for in French language education…but on the whole we have been given a very fair shake.”[31] Meanwhile, David Archer, president of the Ontario Federation of Labour, who the newspaper “cast in the role of a WASP [White Anglo-Saxon Protestant],” expected to hear criticism from other ethnocultural groups about the predominance of Anglo-Saxon culture in Ontario. Despite this perceived antagonism, Archer noted that the real danger to Canada was not inter-ethnic conflict, but the United States’ ‘melting pot’ and the influence of American media. According to the union leader, in a multicultural society the “best of everything is retained and this gives you a much higher level [of culture]. Culture cannot be imposed, however. It has to grow.” Archer concluded by suggesting that Indigenous peoples were left behind and their voices would receive his full support at the conference.[32]

Leslie Currie, president of the Ontario Native League for Youth, initially was critical of the proposed Heritage Ontario conference because it would highlight cultural diversity while ignoring Indigenous cultures in Canada. Currie pointed out that for all cultures to live together, there needed to be an understanding of all cultures, including those of Indigenous peoples. The Indigenous youth leader recalled that while attending school in Toronto, she had learned more about the Doukhobors than her own people. Currie also promoted the inclusion of community members, over “non-native ‘experts’” in the teaching of courses on Indigenous history and culture. She went on to raise the issue of racial discrimination, high rates of Indigenous incarceration at penal institutions across the country, and the effects of social and economic exclusion on Indigenous peoples. Currie concluded that these issues had to be addressed if all cultures were to be valued equally.[33]

What Multiculturalism Means to Me: Concerned Canadians Debate Cultural Plurality

Canadians continued to debate cultural plurality and official multiculturalism across the country. Public views expressed in Canadian newspapers included support for maintaining Canada’s bicultural heritage, promotion of multiculturalism as a means to prevent Quebec separatism, lack of multicultural representation among the “power élite,” and multiculturalism as an “ethnic policy.”

Could an ethnic Canadian, who was neither of English or French origin, truly become Quebecois and maintain his or her cultural identity? This question was posed to delegates attending a June 1972 conference, on the future of Ukrainians in Canada, organized by the Montreal Branch of the Ukrainian Committee of Canada.[34] In his conference address, which was later published in La Presse, author and journalist Roman Rakhmanny argued that Ukrainian Canadians should remember that without the struggle of French Canadians to maintain their language and culture, there would not be another choice (multiculturalism) for Canada’s ethnocultural minorities except the Anglo-Saxon “melting pot.”[35]

That same month, the Toronto Star published an editorial in support of maintaining Canada’s bicultural (English and French) heritage. The editorial claimed that the multiculturalism policy was a “cloudy idea” derived from a “dubious rationale” that could lead to the breakup of the country. The newspaper garnered a strong response from its readership. Toronto resident Ken P. Raudys asserted that the editorial would confirm the fears of some members of Canada’s ethnocultural communities who believed that the mainstream media had failed again “to understand ethnic aspirations to strengthen Canadian unity.” He went on to suggest that Trudeau’s recognition of the country as culturally diverse was most appropriate for a democratic society such as Canada. Raudys concluded that the multiculturalism policy would not undermine French or British institutions and traditions. George C. Koz of Ottawa also disagreed with the Toronto Star editorial and claimed that many individuals had confused the concept of official languages with other expressions of culture. Koz further suggested that a majority of people simply wanted to be Canadians. In addition, Canada did have two founding cultures, but they were not British and French, but rather Aboriginal and Inuit.[36]

As the Canadian government officially legitimized multiculturalism in 1971, ethnocultural leaders were quick to point out that the concept of Canada as a culturally pluralistic society was not new. President of the Ottawa Branch of Ukrainian Canadian Committee, Bohdan Yarymowich informed the Toronto Star that the federal government did not create a multicultural society in Canada, but that it had “merely recognized the facts of life.” He went on to declare that while “Some aspects of our culture are shared by diverse groups such as in the arts, music, sports, and political realms, other aspects remain variable depending on geographic location, ethnic origin, and religious beliefs.” Yarymowich used the example of Irish and Scottish Canadians, who both spoke a common language, but whose cultures were different: “Yet, they are all Canadian.”[37] Marilyn Camp of Concord, Ontario informed the Toronto Star that its editorial had made “the maple syrup in my veins boil.” Camp argued that Canada did have an identity: it was “one of both wild and civilized beauty. It is one of freedom and hope. It is one of welcome to any race or creed. Most important, it is one of peace. Because I am Canadian, I can claim these virtues as my own, for a country is but a reflection of its people.”[38]

In a July 1972 response to a Globe and Mail editorial about how McGill University could link Canada’s English and French cultures and prevent the growth of separatism in Quebec, C.K. Kalevar of Toronto indicated that as an alumnus of the university and a “New Canadian,” who had obtained his landed immigrant status in Montreal and citizenship in Toronto, he felt that “I and many other New Canadians have a stake in Canadian unity.” Kalevar acknowledged that Canadian society had recognized multiculturalism as government policy and that this step would help Canadians recognize “the sociological makeup of Canada.” According to Kalevar, there was a “gross discrepancy [that] cannot be missed” between the ordinary citizens and the “power élite” – in particular, the federal Cabinet which consisted of a French Canadian Prime Minister and an “excessive” number of English Canadian ministers. Kalevar objected to the over-representation of English Canadians and the lack of Indigenous and New Canadian representation in the federal government. He concluded that creating space for representation from these latter two groups could stifle the increasing popularity of separatism: “English Canada may find it hard to accommodate the French, but a truly multicultural Canada can more easily dampen the separatist enthusiasm.”[39]

When the Toronto Star published an editorial, in October 1972, reducing official multiculturalism to an “ethnic policy,” the Provincial Secretary and Minister of Citizenship in Ontario, John Yaremko, replied that the newspaper’s viewpoint demonstrated a “disturbing lack of societal awareness.” According to Yaremko, official multiculturalism could not be dismissed simply as an ethnic policy because it was a “progressive approach to Canadian cultural development” that encouraged all Canadians to contribute to their society through their own cultural heritage. Yaremko asserted that multiculturalism would lead to unity: “unity though diversity.” The Ontario Minister of Citizenship implored the newspaper’s readers to continue to reject “the melting-pot concept,” which he believed had turned ethnocultural groups in other jurisdictions against each other. Yaremko concluded that “We should look instead to a Canadian identity based upon mutual respect for all cultural communities…It is assimilation not multiculturalism which is foreign to the Canadian community.”[40] Over the next decade and beyond, the 1971 official multiculturalism policy continued to draw diverse reactions from concerned Canadians, officials, and media outlets across the country.

Scholars Critique the Official Multiculturalism Policy

In the five decades since Trudeau’s unveiling of an official multiculturalism policy, scholars have studied its origins and legacies. Historian Jack Jedwab points out that the official multiculturalism policy was “an unexpected by-product” of the Bi-Bi Commission. Jedwab notes that the policy was intended to manage francophone nationalism and the effects of the Quiet Revolution in Quebec, and to promote cultural diversity across Canada.[41] Sociologist Peter Li asserts that the official multiculturalism policy was a symbolic recognition of Canada’s cultural diversity rather than a substantive change in government policy.[42] Political scientist Freda Hawkins notes that another factor was behind the federal government’s official multiculturalism policy, a “vague, general feeling of goodwill” towards Canadians of non-British and non-French origin. According to Hawkins, Trudeau’s policy was never meant to be more than a modest contribution to good community relations between federal officials and ethnocultural groups across the country.[43] Journalist Valerie Knowles suggests that Trudeau purposely avoided mentioning that his official multiculturalism policy was politically motivated, and hoped to persuade non-English and non-French Canadians to accept official bilingualism.[44]

In his critique of multiculturalism, Selling Illusions: The Cult of Multiculturalism in Canada (1994, 2002), author Neil Bissoondath argues that by 1971, Trudeau’s government was increasingly becoming unpopular in part due to its federal policy of bilingualism. If official bilingualism was meant to “favour francophone Quebec at the expense of the rest of the country, enhanced multiculturalism could be served up as a way of equalizing the political balance sheet.” Bissoondath concluded that multiculturalism reduced the “Quebecois fact to an ethnic phenomenon.”[45]

In Finding Our Way: Rethinking Ethnocultural Relations in Canada (1998), political philosopher Will Kymlicka, a proponent of multiculturalism in Canada, asserts that critics such as Bissoondath believe that official multiculturalism promotes ethnic separatism among immigrants.[46] According to Kymlicka, multicultural policies do not encourage immigrant groups to separate themselves from public institutions. Rather official multiculturalism revises the “terms of integration, [and is] not a rejection of integration itself.” He goes on to note that if official multiculturalism accepts that immigrants will maintain pride in their ethnocultural identity, then it should be expected that public institutions will also adapt to accommodate this identity. As a result, multiculturalism allows individuals to identify with their ethnocultural group in public, if they wish to do so without fear of stigma or disadvantage: “It has made the possession of an ethnic identity an acceptable, even normal, part of life in the mainstream society.”[47]

Multiculturalism in Canada has come to symbolize an ideology, policy, and reality. According to human rights activist and professor Evelyn Kallen, Canadian multiculturalism is used widely to describe the “social reality of ethnic diversity” in Canada; in reference to official federal government policy “designed to create national unity in ethnic diversity”; and as an “ideology of cultural pluralism (the Canadian mosaic) underlying the federal policy.”[48]

Legacies: Entrenching Multiculturalism in Canada’s Legal Framework

By the 1980s, multiculturalism policy had become increasingly institutionalized while Canada’s population became more diverse due to widespread immigration from around the world. In 1982, the federal government moved to entrench individual rights and protect minority groups with the adoption of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Section 15(1) of the Charter seeks to eliminate expressions of discrimination by guaranteeing equality and fairness for all Canadians under the law, regardless of their race or ethnicity. Meanwhile, Section 27 of the Charter acknowledges the multicultural heritage of Canadians. This acknowledgement helped to place multiculturalism firmly within the constitutional framework of Canadian society.

In 1985, a House of Commons Standing Committee on Multiculturalism was created to examine the status of multiculturalism in Canada. Two years later, the standing committee issued its report which called on the federal government to enact a new policy on multiculturalism and to establish a Department of Multiculturalism. Based on these parliamentary recommendations, a new policy was adopted in 1988.

Nearly two decades after the implementation of the 1971 multiculturalism policy within a bilingual framework, the federal government of Prime Minister Brian Mulroney enacted the Canadian Multiculturalism Act in 1988. Canada became the first country in the world to adopt a national multiculturalism law. The Canadian Multiculturalism Act provided a legislative framework from which to preserve and enhance multiculturalism in Canada.[49] The Canadian Multiculturalism Act recognized “the diversity of Canadians as regards race, national or ethnic origin, colour and religion as a “fundamental characteristic of Canadian society.” Among the Act’s main objectives was the preservation and enhancement of the “multicultural heritage of Canadians, while working to achieve the equality of all Canadians in the economic, social, cultural and political life of Canada…”[50]

Credit: Duncan Cameron / Library and Archives Canada / PA-209871

Credit: Duncan Cameron / Library and Archives Canada / C-46600

- See Victoria Hayward, Romantic Canada (Toronto: Macmillan Company of Canada, 1922). For context, see Ryan McKenney and Benjamin Bryce, “Creating the Canadian Mosaic,” Active History, 16 May 2016, https://activehistory.ca/2016/05/creating-the-canadian-mosaic/.↩

- See Kate Foster, Our Canadian Mosaic (Toronto: YWCA Dominion Council, 1926); McKenney and Bryce, “Creating the Canadian Mosaic.”↩

- For context, see Stuart Henderson, “‘While there is Still Time…’: J. Murray Gibbon and the Spectacle of Difference in Three CPR Folk Festivals, 1928-1931,” Canadian Historical Review 39.1 (Winter 2004): 139-174.↩

- See John Murray Gibbon, Canadian Mosaic: The Making of a Northern Nation (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart).↩

- For context, see James W. St. G. Walker, “Race,” Rights, and the Law in the Supreme Court of Canada (Toronto: The Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History and Wilfrid Laurier Press, 1997), 122-181; and James W. St. G. Walker, “The Law’s Confirmation of Racial Inferiority: Christie v. York,” in The African Canadian Legal Odyssey, ed. Barrington Walker (Toronto: The Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History, 2012), 243-323. After the Second World War, the Canadian parliament and provincial governments outlawed discrimination in the provision of goods and services. In 1975, the Quebec government enacted its Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms, which prevented racial discrimination on the basis of free commerce.↩

- Peter Henshaw, “John Buchan and the British Imperial Origins of Canadian Multiculturalism,” in Canadas of the Mind: The Making and Unmaking of Canadian Nationalisms in the Twentieth Century, ed. Norman Hillmer and Adam Chapnick (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007), 191-192.↩

- The metaphor of an American ‘melting pot’ was popularized by the 1908 play, The Melting Pot, by Israel Zangwill, a British writer of Jewish origin.↩

- G. Laing and Celine Cooper, “Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism,” last modified 24 July 2019, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/royal-commission-on-bilingualism-and-biculturalism.↩

- Elspeth Cameron, “Introduction,” in Multiculturalism and Immigration in Canada: An Introductory Reader, ed. Elspeth Cameron, xv-xxiv (Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press, 2004), xviii.↩

- Laing and Cooper, “Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism.” Following Laurendeau’s death in June 1968, his appointment was assumed by a member of the royal commission, Jean-Louis Gagnon, a journalist, civil servant, and former editor-in-chief of the French-language daily, La Presse.↩

- Library and Archives Canada (hereafter LAC), Privy Council Office (hereafter PCO) fonds, RG 2, Series A-5-a, vol. 6381, file “Cabinet Conclusions, 1944-1979,” item number 2230, title “Canada – The Multicultural Society, a response to book IV of the B & B Commission,” 23 September 1971.↩

- LAC, PCO fonds, RG 2, Series A-5-a, vol. 6381, file “Cabinet Conclusions, 1944-1979,” item number 2230, title “Canada – The Multicultural Society, a response to book IV of the B & B Commission,” 23 September 1971.↩

- LAC, PCO fonds, RG 2, Series A-5-a, vol. 6381, file “Cabinet Conclusions, 1944-1979,” item number 2230, title “Canada – The Multicultural Society, a response to book IV of the B & B Commission,” 23 September 1971.↩

- LAC, PCO fonds, RG 2, Series A-5-a, vol. 6381, file “Cabinet Conclusions, 1944-1979,” item number 2230, title “Canada – The Multicultural Society, a response to book IV of the B & B Commission,” 23 September 1971.↩

- Vianney Carriere, “Ottawa announces grants and incentives to assist immigrants and ethnic groups,” Globe and Mail, 9 October 1971, 53.↩

- Canada, Parliament, House of Commons, House of Commons Debates: Official Report, Third Session – Twenty-Eighth Parliament, Volume 8 (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer for Canada, 1971), 8545.↩

- Freda Hawkins, Canada and Immigration: Public Policy and Public Concern (Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1988), 368.↩

- Laurence Brosseau and Michael Dewing, “Canadian Multiculturalism,” Library of Parliament, 15 September 2009 (Revised on 3 January 2018), https://lop.parl.ca/sites/PublicWebsite/default/en_CA/ResearchPublications/200920E.↩

- House of Commons Debates, 28th Parl., 3rd sess., vol. 8 (1971), 8545.↩

- House of Commons Debates, 28th Parl., 3rd sess., vol. 8 (1971), 8545.↩

- House of Commons Debates, 28th Parl., 3rd sess., vol. 8 (1971), 8546.↩

- House of Commons Debates, 28th Parl., 3rd sess., vol. 8 (1971), 8547.↩

- House of Commons Debates, 28th Parl., 3rd sess., vol. 8 (1971), 8548.↩

- House of Commons Debates, 28th Parl., 3rd sess., vol. 8 (1971), 8548.↩

- Serge Losique, “Le mythe dangereux du multiculturalisme,”Le Devoir, 14 octobre 1971, 4-5.↩

- Michael Behiels, “Une politique qui exprime la réalité canadienne,” Le Devoir, 22 octobre 1971, 4.↩

- Albert Deloras-Billot, “Le mythe du multiculturalisme,” Le Devoir, 25 octobre 1971, 4; Fernand Dumont, “L’avènement du multiculturalisme,” Le Devoir, 26 octobre 1971, 5; Claude Jasmin, “Les manœuvres de diversion des defenseurs du statu quo,” Le Devoir, 6 novembre 1971, 4; Louis Landry, “Biculturalisme ou multiculturalisme? Un autre débat stérile,” Le Devoir, 6 décembre 1971, 4.↩

- Bob Pennington, “Ontario’s Cultural Mosaic: Most delegates – but not all – are happy about our big multicultural conference,” Toronto Star, 29 April 1972, 23. See also, “Germans, Italians, Indians, French protest ‘images,’” Toronto Star, 3 June 1972, 4.↩

- Bob Pennington, “Ontario’s Cultural Mosaic: The Portuguese: ‘A deprived group,’” Toronto Star, 29 April 1972, 23.↩

- Bob Pennington, “Ontario’s Cultural Mosaic: ‘I resent being categorized as Ukrainian,’” Toronto Star, 29 April 1972, 23. For context, see John Porter, The Vertical Mosaic: An Analysis of Social Class and Power in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1965).↩

- Bob Pennington, “Ontario’s Cultural Mosaic: French Canadians are ‘fairly content,’” Toronto Star, 29 April 1972, 23.↩

- Bob Pennington, “Ontario’s Cultural Mosaic: A WASP: ‘Culture cannot be imposed,’” Toronto Star, 29 April 1972, 23.↩

- Bob Pennington, “Ontario’s Cultural Mosaic: An Indian: ‘Native people are subject to racial slurs,’” Toronto Star, 29 April 1972, 23.↩

- Vincent Prince, “Les minoritiés au Québec,” La Presse, 13 juin 1972, A4.↩

- Roman Rakhmanny, “L’unité dans la diversité,” La Presse, 1 juillet 1972, A4.↩

- “‘Cultural diversity aids Canadian unity,’” Toronto Star, 13 June 1972, 7.↩

- B. Yarymowich, “‘Multi-culturalism not a new concept,’” Toronto Star, 13 June 1972, 7.↩

- Marilyn Camp, “‘Maple syrup in my veins boils at foolish phrases,’” Toronto Star, 13 June 1972, 7.↩

- C.K. Kalevar, “French and English,” Globe and Mail, 19 July 1972, 6.↩

- John Yaremko, “‘We must reject melting-pot concept,’” Toronto Star, 1 November 1971, 7.↩

- Jack Jedwab, “Multiculturalism,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, last modified 20 March 2020, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/multiculturalism.↩

- Peter S. Li, “The Multiculturalism Debate,” in Race and Ethnic Relations in Canada, ed. Peter S. Li (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1999), 152.↩

- Hawkins, 390.↩

- Valerie Knowles, Strangers at Our Gates: Canadian Immigration and Immigration Policy, 1540-2015 (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2016), 219.↩

- Neil Bissoondath, Selling Illusions: The Cult of Multiculturalism in Canada (Toronto: Penguin Canada, 2002), 36-37.↩

- Will Kymlicka, Finding Our Way: Rethinking Ethnocultural Relations in Canada (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1998), 16.↩

- Kymlicka, Finding Our Way, 44. Kymlicka argues that multiculturalism in Canada is successful due to high rates of naturalization, intermarriage, political participation among ethnocultural groups, and ability of immigrants to speak either English or French. According to him, multiculturalism has not promoted ethnic separateness (see pages 15-24).↩

- Evelyn Kallen, “Multiculturalism: Ideology, Policy and Reality,” in Multiculturalism and Immigration in Canada: An Introductory Reader, ed. Elspeth Cameron, 75-96 (Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press, 2004), 75.↩

- Brosseau and Dewing, “Canadian Multiculturalism.”↩

- LAC, Statutes of Canada, An Act for the Preservation and Enhancement of Multiculturalism in Canada, 1988, SC 36-37 Elizabeth II, vol. I, Ch. 31, 836-838.↩