by Jan Raska, PhD, Historian

(Updated August 21, 2020)

Origins of Canada’s Refugee Determination System

The origins of Canada’s refugee determination system can be traced back to 1922, when the League of Nations (a predecessor to the United Nations (UN)) established the Nansen Passport which provided refugees with an internationally recognized travel document. The passport served as a travel certificate establishing a refugee’s identity. Recognized by more than 50 countries and initially destined for use by over 1.5 million individuals displaced by the First World War and the Russian Revolution, Canadian officials hesitated to legitimize the travel certificate out of a fear that it was a “one-way document.” This was the case for a movement of orphans who had survived the Armenian Genocide and sought permanent resettlement in Canada. They were later resettled through an exemption to an order-in-council that had further restricted “Asiatic” immigration to Canada.[1] Despite international attempts to provide refugees and stateless persons with recognized travel documentation, the Canadian government maintained its sovereign right to deport persons belonging to any of the “prohibited classes” defined in the 1910 Immigration Act.

Without an international treaty that defined who was a refugee and established the obligations of states towards these individuals, Canadian immigration officials relied on domestic immigration legislation, regulations, and official discretion to admit, detain, or refuse entry to individuals in search of asylum. The Canadian government admitted refugees based on prevailing sociocultural, economic, and political views of the ‘desirable’ immigrant. For example, in the 1930s, Canada restricted the admission of European Jews who sought safe haven from anti-Semitism and the emergence of fascism in Germany, but welcomed Sudeten Germans from Czechoslovakia in search of refuge.[2]

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the UN established the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which recognized the right of individuals to seek asylum from persecution in another country. The Canadian government was an early participant in negotiations to establish an international framework for refugees. In 1951, Canada was one of twenty-six countries to send a delegate to participate in the UN Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Status of Refugees and Stateless Persons. Following successful negotiations, the UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees was approved and came into force in 1954. The Canadian government opted not to sign the convention because articles 26 (freedom of movement), 27 (identity papers), and 28 (travel documents) appeared to grant these rights to refugees.[3] The convention also prevented Canadian officials from deporting individuals because it guaranteed asylum as an international human right and protected convention refugees from being forcibly returned to their country of origin (non-refoulement). While the federal cabinet concluded that the convention was between countries (signatories) and did not confer rights to individuals, it observed that it was likely that there would be a sentiment among its international partners that the convention did provide individuals with rights.[4]

Although Canadian authorities used the convention as a reference point when processing refugees for permanent resettlement in Canada, it would take nearly two decades before the federal government ratified the UN refugee convention in 1969. Recognizing that an active federal policy towards refugees had become a necessity as sudden Cold War crises forced thousands to seek safe haven in the West, the Canadian government demonstrated its commitment to international humanitarianism by ratifying the refugee convention. Within a few years, federal officials implemented a framework to address the increasing need to process refugee claimants who arrived at Canada’s borders or individuals already in Canada who had made an in-land claim for refugee status.

Formalizing a Canadian Refugee Determination System

In 1973, the Canadian government established its first formal administrative structure to deal with refugee claimants. An interdepartmental committee comprised of representatives from the Departments of External Affairs and Manpower and Immigration met to assess individual claims and forward their recommendations to the Minister of Manpower and Immigration who had the authority to decide whether a refugee claimant would remain in Canada or be deported. This nascent framework was strengthened later by the 1976 Immigration Act in which refugees were defined as a distinct group of immigrants (humanitarian class) for the very first time.

Canadian journalist Victor Malarek points out that the existing framework was soon stuck in bureaucratic red tape and procedural disputes. In 1980, Minister of Employment and Immigration, Lloyd Axworthy, established a task force with the goal of improving and streamlining the refugee determination system. The task force made three recommendations, all of which were later implemented. First, a Refugee Status Advisory Committee (RSAC) was formed as an independent body in an attempt to distance its work from the Departments of External Affairs and Employment and Immigration. Second, the UN refugee convention was not only to be applied directly according to its wording, but also in spirit. Third, the task force recommended that refugee claimants be given an oral hearing during the determination process. This recommendation was widely supported by refugee advocates who supported a balanced and fair determination process. In 1983, the oral hearing–which is now a standard component of an Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRB) hearing–began as a pilot project in Toronto and Montreal. In other instances, refugee claimants recorded their testimonies into an audio recorder before Canadian immigration officials. Despite these changes, the federal government continued to claim that its most effective contribution to the world refugee crisis was to assist refugees and international organizations abroad rather than permanently resettling refugees in Canada.[5]

Before the implementation of the oral hearing, refugee claimants were immediately obligated upon entry to report to a Canadian immigration official in order to request asylum. If the refugee claimant was found to be inadmissible, they were sent to an immigration inquiry in order to determine whether they should be deported from the country. If the individual had not previously requested asylum, they could do so then and the removal order against them would be stayed. The refugee claimant would then be interviewed by a senior immigration official and a transcript of the interview would be sent to the recently created RSAC. The committee would review the application for asylum and make a recommendation to the federal immigration minister. If a claimant was deemed to not qualify for refugee status, their application could also be considered under humanitarian and compassionate grounds. If a claimant’s application for asylum was rejected by the minister, they could appeal the decision to the Immigration and Appeal Board (IAB) and if unsuccessful, to the Federal Court of Canada.[6]

Re-evaluating the Effectiveness of Canada’s Refugee Determination System

Although the early refugee determination process provided claimants with the possibility of appealing a negative outcome, the system remained partial to the interests of the federal government rather than the claimant. In the early 1980s, the Canadian government re-evaluated the effectiveness of its refugee determination system. The submission of successive reports, Illegal Migrants in Canada (Robertson Report, 1983) and A New Refugee Status Determination Process for Canada (Ratushny Report, 1984) found that Canada’s refugee determination system was rife with anomalies, inconsistencies, and susceptible to abuse. The reports recommended that further capacity and resources be allocated to adjudicating refugee claims.[7]

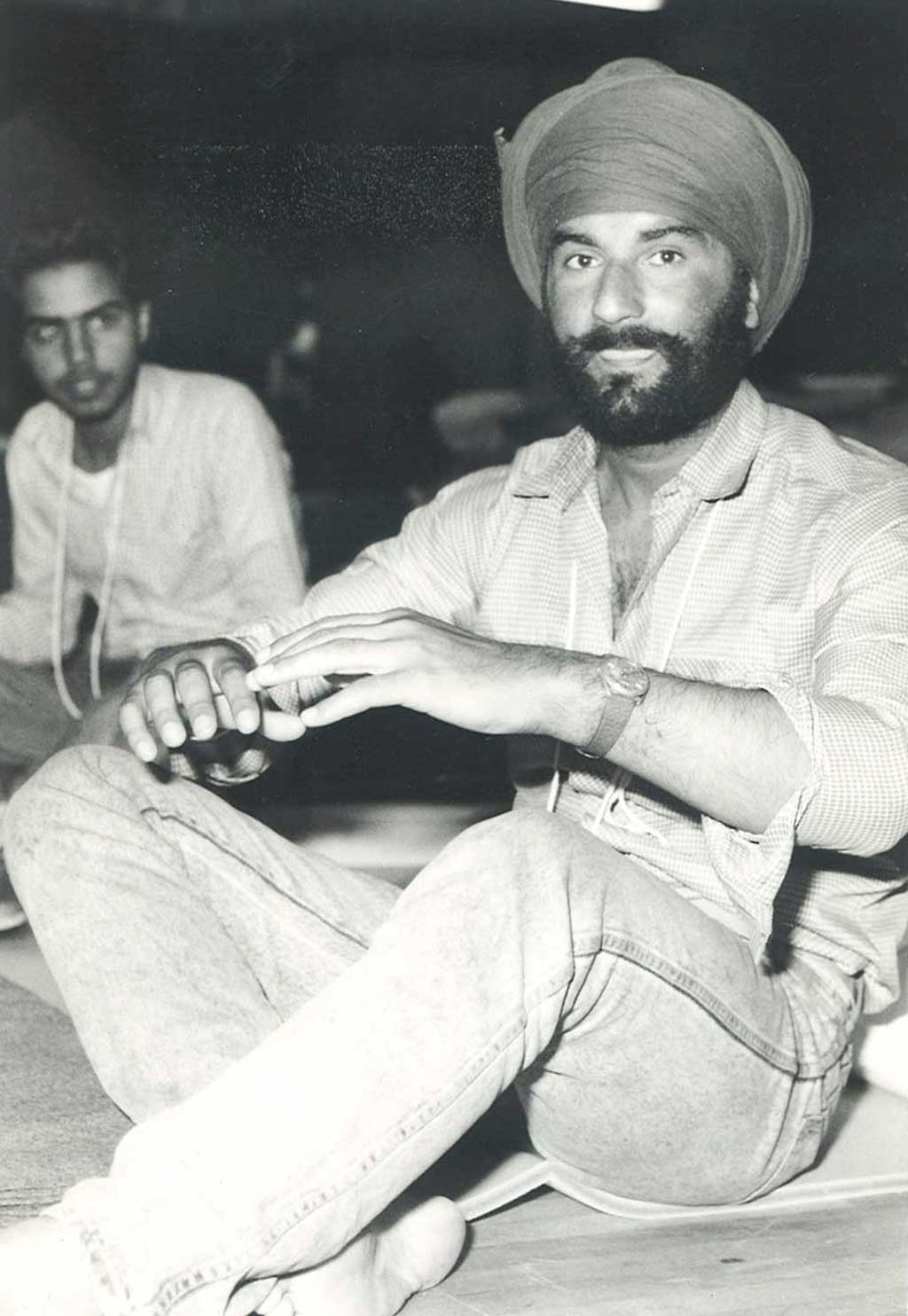

Soon the Robertson and Ratushny reports were overshadowed by a landmark court decision. In 1985, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled in Singh v Minister of Employment and Immigration that refugee claimants in Canada were entitled to fundamental justice under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The ruling was the result of individual appeals by seven claimants (six Sikhs with Indian citizenship and one Guyanese citizen of Indian heritage) who had claimed convention refugee status upon arrival in Canada. Due to the similarities in their cases, all seven individuals were dealt with in one case. Their claims for asylum were rejected and they were denied a subsequent hearing before the IAB. The group led by Harbhajan Singh argued that the procedure was unconstitutional because it violated section 7 (“life, liberty, and security of the person and not to be denied thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice”) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. A majority of the Supreme Court justices sided with the appellants and ruled that the application of fundamental justice required that a refugee claimant’s credibility be determined by an oral hearing at some point in the refugee determination process.[8]

That year, the Canadian government commissioned another study of its refugee determination system. Thirteen days after the landmark court decision, Rabbi Gunther Plaut submitted his report, Refugee Determination in Canada (Plaut Report, 1985). The report outlined several different structures for a more equitable and balanced refugee determination system including oral hearings, an independent decision-making body to examine claims, a full appeal process, and regional decision-making across the country. In light of the three successive reports and the Singh decision, procedural fairness for inland refugee claims became an urgent issue for federal officials and refugee advocates. With over 63,000 refugee claimants now awaiting a full oral hearing in light of the Supreme Court’s decision, the Canadian government held an administrative review and decided to provide amnesty to refugee claimants who had entered Canada before 21 May 1986. Individuals were permitted to stay in Canada and become permanent residents if they were already employed or likely to secure employment in the near future.[9]

Heightened Public Tensions over Refugee Claims

Over the past several decades, the refugee question has garnered increased public attention and media coverage resulting in a national debate about immigration. In the early 1960s, the world’s refugee population comprised approximately 1.2 million individuals. By the end of the 1980s, that number had reached nearly 15 million people due to political instability, interethnic strife, persecution, war, famine, and natural disaster. While individuals with UN refugee status applied for permanent resettlement in Canada from countries of asylum, an increasing number of individuals entered the country to make an in-land claim for refugee status. The increase in refugee claims stemmed in part from the arrival of “illegal” or “undocumented” migrants who sought personal security and economic opportunity in the West–notably in North America, Western Europe, and Oceania. Many of these refugee claimants did not meet the United Nations convention definition of a refugee, but believed that claiming asylum was their best path towards permanent residency in Canada. In 1986 alone, approximately 18,000 claims for refugee status were made in Canada, of which two-thirds were determined by Canadian officials to be unfounded claims for refugee status.[10]

Tamil and Sikh Refugee Claimants on Canada’s East Coast

During this period, two separate groups of refugee claimants received widespread media attention and heightened public interest in Canada’s immigration policy and its refugee determination system. In 1986, 135 Tamils, originally from Sri Lanka, were rescued off the southern coast of Newfoundland and brought to St. John’s for immigration processing. Canadian officials discovered that the group had spent thirty-five days in a ship’s hold of a West German freighter before being left to fend for themselves in lifeboats. Since the boats carried no identification, Canadian Coast Guard officials became suspicious that the Tamils were attempting to gain entry into the country ‘illegally.’ The Tamils later admitted to paying $3,450 each for their passage to Canadian waters. Despite some public opposition depicting the Tamils as queue jumpers and circumventing the Canadian immigration system, the Tamils were granted one-year ministerial permits allowing them to remain in Canada as landed immigrants.[11]

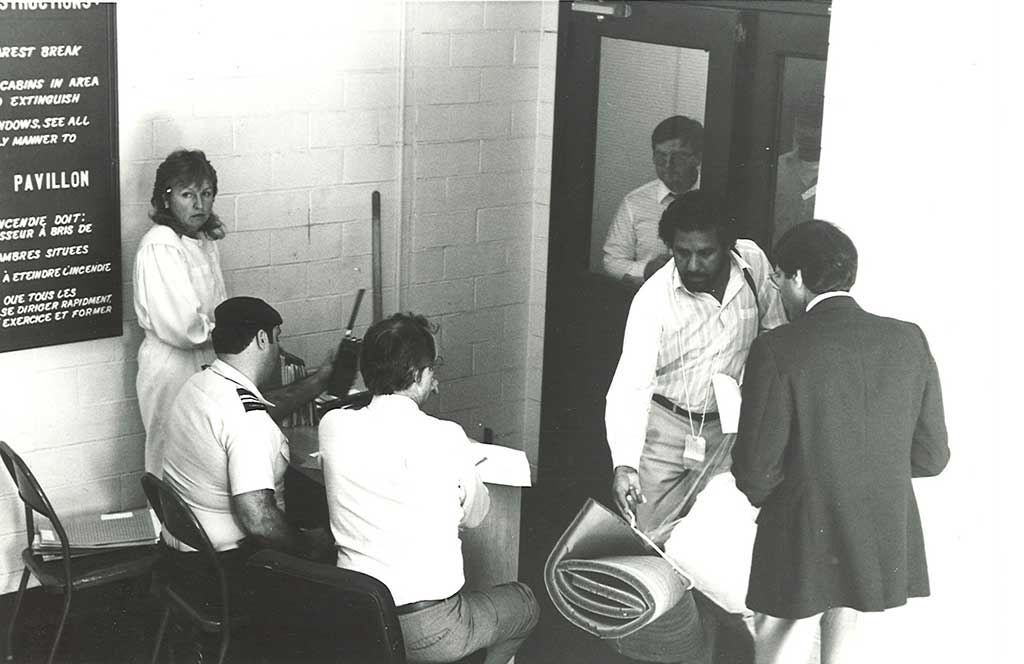

Less than a year after the arrival of the Tamils in Newfoundland, 174 Sikhs arrived by lifeboat near the fishing village of Charlesville, Nova Scotia. While some villagers were afraid, others welcomed the new arrivals and provided them with refreshments. Locals then contacted the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and the refugee claimants were transported by school buses to Canadian Forces Base Halifax for immigration processing. The subsequent media coverage brought further attention to their irregular arrival and claims for refugee status resulting from persecution for their Sikh religious beliefs back in India. Shortly after the Sikhs’ arrival, the federal government recalled parliament for an emergency session to amend the Immigration Act. A result of these changes was Bill C-84 (the Refugee Deterrents and Detention Bill) which brought a number of draconian provisions into law, including giving Canadian officials the right to turn away ships suspected of bringing bogus refugee claimants to Canada’s shores. Due to public outrage from refugee advocates, churches, and humanitarian organizations this provision was later dropped.[12]

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (DI2019.171.1)

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (DI2019.171.2)

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (DI2019.171.7)

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (DI2019.171.15)

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (DI2019.171.16)

Ironic Timing? Canada Receives the Nansen Refugee Award

Approximately two months after the Tamils’ controversial arrival in Canada, in October 1986, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) awarded its annual Nansen Refugee Award – the UN’s highest distinction bestowed to individuals and organizations for their aid to refugees–to the people of Canada “in recognition of the major and sustained contribution made to the cause of refugees in their country and throughout the world over the years.” Prior to 1986, no country had ever received the award. The Nansen Refugee Award recognized Canada’s role as a major contributor to international humanitarianism and for its recent contribution in permanently resettling Southeast Asian, Eastern European, and Latin American refugees in the 1970s and 1980s. The timing of the award was ironic given that Canadians were divided over the efficacy of their refugee determination system and the irregular arrival of refugee claimants, some of whom were labelled by the media as ‘illegal’ immigrants or ‘bogus’ refugee claimants who sought to jump an immigration ‘queue.’[13] Under international law, individuals have the right to request asylum upon reaching Canada and are also obligated to report promptly to Canadian officials in order to demonstrate “good cause” for their arrival.[14] There is no line or ‘queue’ in Canada’s immigration system for individuals in search of asylum. Refugees and potential immigrants are assessed on a case by case basis, with refugees often facing processing times that are double those of other potential immigrants.[15]

Renewing the National Debate about Canada’s Refugee Policy

One positive outcome from the widespread media attention and public outrage over Bill-C-84 was a renewed national debate about Canada’s refugee policy. Before the 1980s, persons seeking to enter Canada as refugees claimed asylum overseas and applied at the nearest Canadian government office where their application was processed. They could also make a claim for refugee status after arriving in Canada. Prior to the 1976 Immigration Act, inland claims occurred at the level of hundreds per year. Individual orders-in-council granted a person status in Canada at the minister’s discretion and were based in part on humanitarian, economic, and political considerations.

Although refugees were not subject to the points system (introduced in 1967), they were nevertheless assessed in order to determine their ability to adapt to Canadian society and its economy. During this decade, an increasing number of refugee claimants bypassed this established framework and arrived in Canada in the hopes of securing asylum. Historian Valerie Knowles points out that the unpredictable arrival of these claimants coupled with the complicated process of determining the validity of their claims made it difficult for Canadian authorities to establish an immigration program that would embrace pre-established levels of immigration from the family, economic, and humanitarian classes. The arrival of individuals in Canada whose refugee claims were proven later to be false continued to spark debate between churches, humanitarian organizations, and supporters of a tightly controlled immigration program who disagreed on how to process in-land refugee claimants.[16]

A New Refugee Determination Process: The Creation of the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada

Determined to restrict the number of individuals whose claims for refugee status were unfounded, in 1987, the Canadian government introduced Bill C-55 (Refugee Reform Bill) which sought to clear-up the backlog of refugee claimants in Canada and reduce the amount of time required to adjudicate an application for refugee status. The legislation also provided for the establishment of the IRB which was to be comprised of the existing IAB and a new Convention Refugee Determination Board, which would deal exclusively with refugee matters. Refugee claimants would be given the right to present their case before a board hearing. Later that year, Gordon Fairweather, a former Attorney General of New Brunswick and the first Chief Commissioner of the Canadian Human Rights Commission, was appointed Chairman of the IRB.

The new refugee determination process was meant to modernize a system that had become inefficient, but led ultimately to controversy once refugee advocates discovered that the new legislation permitted Canadian immigration officers to deny entry to refugee claimants who had arrived from a safe third country, where they could have filed a claim for refugee status. Within the international refugee regime, refugees are expected to claim asylum in a second country, before seeking refugee status and permanent resettlement in a safe third country. Refugee advocates argued that some third countries could return refugees to their country of origin, therefore the Canadian government should permit refugee claimants from safe third countries to enter the country so that they could make a new claim for refugee status in Canada. Before Bill C-55 came into effect in 1989, the number of claims for refugee status continued to grow because of international instability and existing inefficiencies in the refugee determination system. The backlog in Canada’s refugee determination system rose to tens of thousands of individuals.[17]

In a 1988 press release, the IRB claimed that in recent years approximately 70 percent of all claims for refugee status were rejected after examination. According to the board, many refugee claimants were using the refugee determination system in an attempt to avoid the regular immigration process in the hopes of rapidly attaining permanent resident status. With large delays in the previous system, claimants could remain in Canada for several years before their cases were decided.

Streamlining Canada’s Refugee Determination System

Following consultations with refugee advocates and humanitarian organizations, and the commission of three reports on Canada’s existing refugee determination system, IRB chairman Gordon Fairweather visited the offices of the UNHCR in Geneva to discuss policy and procedures in order to streamline the determination process in Canada, and to determine the availability of documentation on human rights abuses around the world. Federal officials also visited Britain, West Germany, Netherlands, Sweden, and Denmark to evaluate the efficacy of their individual refugee determination systems and compare them to the process being implemented in Canada.[18]

At the beginning of the 1980s, the number of refugee claims numbered some 1,600 cases. By 1988, that number had risen to over 60,000 cases. The Minister of Employment and Immigration had estimated that it would take approximately two years for each case to be decided. The establishment of the IRB was part of the federal government’s attempts to instill fairness into Canada’s refugee determination system, and lead to faster and non-adversarial hearings that also gave the refugee claimant the benefit of the doubt. In order to reject a claim, the two-member panel had to unanimously agree otherwise a single member’s positive decision lead to an individual receiving refugee status in Canada. The refugee determination system was also charged with confirming as quickly as possible the status of genuine refugees in accordance with Canada’s humanitarian traditions; ensuring that individuals and groups could not use the refugee determination system to circumvent existing immigration policies; and reassuring Canada’s international partners that it maintained an effective and humane process that upheld its international commitments within the international refugee regime.[19]

Conclusion: Canada’s Refugee Determination System as an International Model in the Adjudication of Refugee Claims

Over the past several decades, Canada’s refugee determination system has come under scrutiny for its lack of procedural fairness and equity, inefficiencies, delays, and backlogs. These issues were the result of a structure in need of modernization to meet Canada’s international humanitarian obligations including giving individuals the ability to provide their own testimony as part of their claim for refugee status. Another significant shift occurred in 1993, when Canada became the first country in the world to recognize gender and sexual orientation-related persecuation as a basis for claiming asylum. The IRB’s first women Chairperson, Nurjehan Mawani, issued “Guidelines on Women Refugee Claimants Fearing Gender-Related Persecution,” which provided adjudicators with “guiding principles” when managing relevant cases.[20] In addition to gender, various forms of individual or group persecution, war, famine, and natural disaster continued to be the main reasons for a sharp rise in the number of refugee claimants seeking to enter Canada. This was the case from the 1980s onwards, when an increasing number of claimants arrived at Canadian ports of entry and other locations along Canada’s borders. Their arrival ignited a national conversation about how Canada processed refugee claimants and whether the country’s immigration policies were contributing to an inefficient refugee determination system.

Today, Canada’s refugee determination system is respected around the world for providing equity and fairness in adjudicating an individual’s claim for refugee status. As Canada’s largest administrative tribunal, the IRB serves an important role in the Canadian immigration system because it is tasked with making “well-reasoned decisions on immigration and refugee matters, efficiently, fairly and in accordance with the law.”[21] One of its principal responsibilities is to decide who requires refugee protection among thousands of refugee claimants who enter Canada each year.

As of 2018, the UNHCR (the UN Refugee Agency) estimates that over 68.5 million people are forcibly displaced. This figure includes 40 million Internally Displaced People (IDPs), 25.4 million refugees, and 3.1 million asylum-seekers[22]. Given the growing forcibly displaced population around the word, the IRB will play an important role in applying Canadian immigration regulations and shaping the future of Canada’s refugee determination system.[23]

- Jack Apramian, The Georgetown Boys (Zoryan Institute of Canada, 2009), xxxv-xxxvi. For further context, see Isabel Kaprielian-Churchill, “Rejecting ‘Misfits:’ Canada and the Nansen Passport,” International Migration Review 28.2 (1994): 285.↩

- See Irving Abella and Harold Troper, None Is Too Many: Canada and the Jews of Europe, 1933-1948 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012); and Gerald Dirks, Canada’s Refugee Policy: Indifference or Opportunism? (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press).↩

- Library and Archives Canada (hereafter LAC), Privy Council Office (hereafter PCO) fonds, RG 2, Series A-5-a, vol. 2648, file “Cabinet Conclusions,” item 11112, title “United Nations; Convention on Refugees and Protocol on Stateless Persons; Canadian participation,” 29 June 1951, 1-2, reel T-2367.↩

- LAC, PCO fonds, RG 2, Series A-5-a, vol. 2648, file “Cabinet Conclusions,” item 11117, title “United Nations; Convention on Refugees and Protocol on Stateless Persons,” 4 July 1951, reel T-2367.↩

- Victor Malarek, Haven’s Gate: Canada’s Immigration Fiasco (Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1987), 106-107.↩

- Ninette Kelley and Michael Trebilcock, The Making of the Mosaic: A History of Canadian Immigration Policy (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010), 401.↩

- Malarek, Haven’s Gate, 108; Kelley and Trebilock, Making of the Mosaic, 402.↩

- Kelley and Trebilcock, Making of the Mosaic, 402-403; Valerie Knowles, Strangers at Our Gates: Canadian Immigration and Immigration Policy, 1540-2015 (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2016), 226; Reginald Whitaker, Double Standard: The Secret History of Canadian Immigration (Toronto: Orpen & Dennys, 1987), 292-293; Singh v. Minister of Employment and Immigration, [1985] 1 S.C.R. 177, accessed 26 February 2019, https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/39/index.do.↩

- Malarek, Haven’s Gate, 108; Kelley and Trebilock, Making of the Mosaic, 402; Knowles, Strangers at Our Gates, 226-227; Howard Adelman, “The Plaut Report,” Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees 5.1 (1985): 3-6.↩

- Knowles, Strangers at Our Gates, 221-222; Malarek, Haven’s Gate, 136-149.↩

- CBC Digital Archives, “1986: Sri Lankan migrants rescued off Newfoundland,” accessed 15 February 2019, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/nl-tamil-rescue-35th-anniversary-1.6131947; Knowles, Strangers at Our Gates, 222; Malarek, Haven’s Gate, 136-149; Mark Kingwell, “Tamils get right to work while their status is considered,” Globe and Mail, 15 August 1986, A4.↩

- Shawna Richer, “Sikh refugees revisit N.S. coast 17 years later,” Globe and Mail, 14 July 2004, accessed 15 February 2019, https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/1707584996. Knowles, Strangers at Our Gates, 222-223.↩

- Reuters, “U.N. Awards Medal to Canada for Its Contributions to Cause of Refugees, accessed 26 February 2019, http://articles.latimes.com/1986-10-07/news/mn-5066_1_nansen-medal.↩

- Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (hereafter UNHCR), “Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees,” accessed 7 March 2019, https://www.unhcr.org/3b66c2aa10. See page 29.↩

- Canadian Association of Refugee Lawyers, “Challenging the Myths: The Truth about Canadian Refugee Law,” accessed 25 March 2019, https://carl-acaadr.ca/challenging-myths/. See number 7; Canadian Council of Refugees, “Refugees: Myths…Busted!” September 2016, accessed 25 March 2019, http://ccrweb.ca/sites/ccrweb.ca/files/infographic_refugee_myths.pdf. See page 3.↩

- Knowles, Strangers at Our Gates, 224.↩

- Knowles, Strangers at Our Gates, 227-228. See also Freda Hawkins, Canada and Immigration: Public Policy and Public Concern (Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1988), 388-389; IRB, “News Release,” 30 August 1988. See “2. Biographical Material.”↩

- Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (hereafter IRB), “Backgrounder: On Establishment of IRB,” 30 August 1988. See “Abuses of the Canadian Refugee System,” and “Designing the IRB and Its Rules.”↩

- IRB, Refugee Determination: What It Is and How It Works (Ottawa: IRB, 1989), 3, 10.↩

- IRB, “Chairperson Guidelines 4: Women Refugee Claimants Fearing Gender-Related Persecution,” accessed 8 March 2019, https://irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/legal-policy/policies/Pages/GuideDir04.aspx; See also, Judith Ramirez, “The Canadian Guidelines On Women Refugee Claimants Fearing Gender-Related Persecution,” Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees 14.7 (December 1994): 3-7.↩

- IRB, “Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada,” accessed 15 February 2019, https://irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/Pages/index.aspx.↩

- UNHCR, “Figures at a Glance,” accessed 28 February 2019, https://www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html.↩

- IRB, “Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada.”↩