by Daniel Meister, PhD

Introduction

The first part of this article traced the origins of the Barr Colony and its leaders. It demonstrated that the colony was part of the broader process of British colonialism and was inspired by a desire for colonies to be composed of mostly British settlers. The group of nearly 2,000 immigrants who had been inspired by Barr and Lloyd’s campaign sailed from England to Canada, arriving on the east coast and then travelling by train across the country. When we left them, the colonists were just pulling out of the station at Regina, Saskatchewan, as the gathered crowd joined them in singing “O Canada” …

From Saskatoon to the Reserved Land

When the trains finally arrived in Saskatoon on April 17, 1903, the colonists were greeted by C.W. Speers, the government’s Colonization Agent, who gave a short speech. Drawing on notions of British racial superiority, he encouraged them that “there would be difficulties to face, but they belonged to a race whose sons never turned back in the face of trouble.”[1]

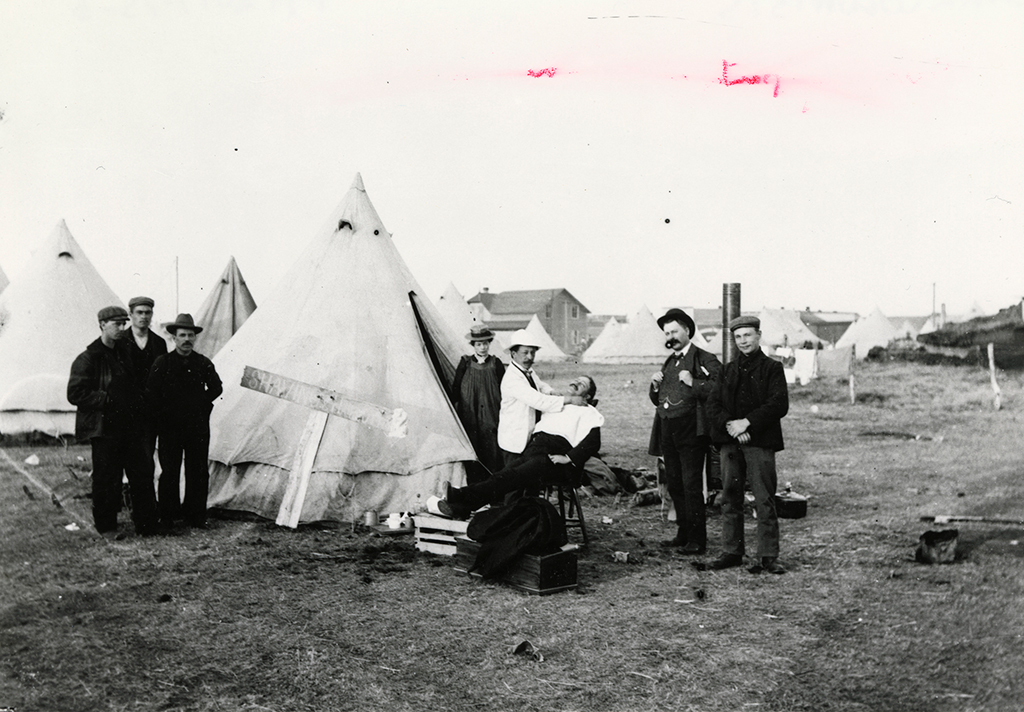

Credit: Saskatoon Public Library, General Photographs Collection, item PH-2014-131. Photo courtesy of Saskatoon Public Library.

Because there would not be nearly enough accommodations in what was then a small village, a tent city called “Canvas Town” had been set up on the banks of the Saskatchewan River using the tents that Barr had ordered. Here the social distinctions of their homeland had been replicated, with the hospital, Barr’s tent, and the tents of the wealthier colonists clustered at one end.

Some colonists still found accommodations were lacking; common complaints included the way baggage had been handled, a lack of clean drinking water, and the price of supplies. Given that the transportation plans had fallen apart, colonists had to obtain horses, oxen, or at least a ride to the colony. Isaac’s brother, Jack, was also there selling horses, but he gained a reputation as a rather dodgy character. “They weren’t supposed to be over nine years of age but I know some of those animals must have been with Noah when he came out of the ark,” one colonist recalled.[2]

Once government officials found out that nearly 200 people, including some families, did not have sufficient funds, they arranged to interview and find jobs for them. Forty men were sent to Prince Albert and 110 to Moose Jaw to work on the railroad, while the remainder found jobs in Saskatoon. A handful of families decided that the lifestyle was not for them, and began the return trip to England.[3]

Credit: Library and Archives Canada (hereafter LAC), item number 323930.

Credit: Saskatoon Public Library, General Photographs Collection, item PH-2017-73-6. Photo courtesy of Saskatoon Public Library.

The remaining colonists headed out on the trail to Battleford, a five-day trip. A few had professional help: between thirty and forty Indigenous freighters brought horses and wagons to Saskatoon and were hired by colonists to transport them and their goods to the site.[4] Some found the trip smooth, those less experienced had more difficulties, and a handful chose this point to quit and return to Britain. Once reaching Battleford, the remaining colonists rested in tents provided by the Department of the Interior, or in the immigration hall. Around twenty colonists found temporary work to finance the remainder of their trip. The rest of the group purchased additional provisions and then departed for the final 80 to 96-kilometre trek to their reserved land. In the middle of this trip, a baby was born in a tent, while the mother had for comfort only blankets thrown on the frozen ground.[5]

Establishing a Colony

It is unclear how many colonists remained at this point, as some traveled to nearby settlements to find work. Barr later reported that 600 homesteads were claimed, so the figure of between 1,200 and 1,600 settlers seems reasonable.[6] But the early days were marked by conflict: the colonists’ simmering resentment towards Barr quickly boiled over and, shortly after their arrival, they ousted him as their leader. Although other parties deserved some of the blame, such as the steamship company and the railway (which misplaced a great deal of their luggage), many colonists pinned all their frustrations on Barr.

As his biographer remarks: “Barr was quick tempered and undiplomatic … and as his arrangements gradually fell apart and his promises faded the colonists became bitter with disillusion.” Tensions amongst the colonists were so high that the North West Mounted Police (NWMP, the forerunner to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP)) felt compelled to send a constable to the settlement to keep the peace. However, the NWMP found that, due to the settlers’ inexperience, their role “had little to do with crime and a great deal to do with human welfare.”[7]

The most charitable interpretation is that Barr’s plan had grown to the point that he was unable to manage it; however, his inability to delegate ensured his failure as a leader. The colonists then asked Lloyd to take charge, as they had been turning to him with their problems since the sea voyage, but he refused to be the sole leader. Taking the biblical model of Jesus and the twelve disciples, in the end Lloyd and a committee of twelve were appointed the group’s new leaders.

After a heated public meeting, Barr agreed to resign and turn over all his books to the new committee. He too had taken out a homestead at the site but, at the committee’s request, agreed to forfeit this as well. Although there are many apocryphal tales of Barr fleeing the settlement and being pursued by angry, armed colonists, it appears he lingered a bit longer, trying to settle his accounts, before departing. However, public resentment towards him was so high that he was pelted with rotten eggs when boarding the train in Regina. Adding insult to injury, the settlers later voted that their townships would be called Britannia and that the first town would be called Lloydminster, after their new leader.[8]

Lloydminster Under its Namesake

Yet Lloyd’s leadership also garnered mixed reviews. As one colonist put it, “we liked Lloyd very, very much, but he was a dictator with very strong ideas.” He was arrogant, outspoken, and insistent on crafting a community with the highest moral standards, which to him meant keeping it all-British and making it alcohol-free. One group of settlers who believed they would benefit from the inclusion of some experienced farmers, regardless of their nationality, eventually left the colony and settled in nearby Jackfish.

The question of temperance proved equally divisive and eventually split Lloydminster into two factions.[9] Lloyd, however, did not meet the same end as Barr, for in 1905 the Bishop of Saskatchewan, Jervois A. Newnham, asked Lloyd to serve as Archdeacon and General Superintendent of all “white missions” for the diocese. Lloyd accepted and moved from Lloydminster to Prince Albert, where he became a valued church administrator and, later, a controversial nativist.[10]

Despite the odds and internal strife, the colony quickly put down roots. The group arrived at their reserved land in early May and got busy “ploughing or ‘breaking’ the virgin sod, hauling poplar logs for building shacks or log-cabins,” though sod-houses with the thatch made from the long slough-grasses were equally common.[11] Of course, those who had the most initial success as farmers were invariably those who had a combination of previous farm experience and plenty of funds at their disposal, though there were some amateurs who went on to become prosperous farmers despite numerous setbacks.[12]

Credit: LAC, R231-1653-6-E, item number 3517732.

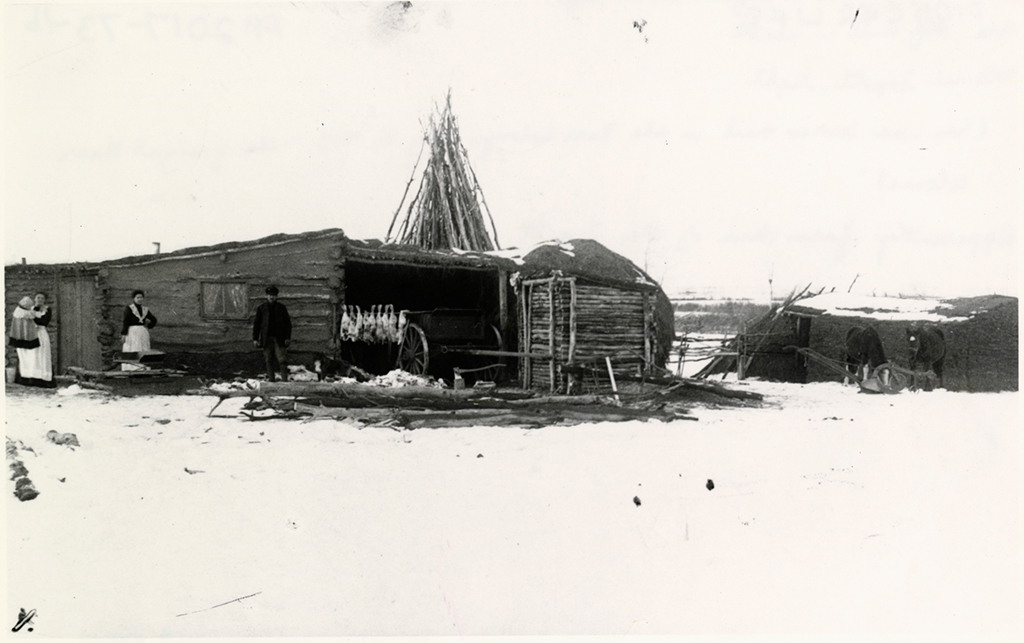

Credit: Saskatchewan Public Library, General Photographs Collection, PH-2017-73-16. Photo courtesy of Saskatoon Public Library. Description reads: “Mrs. W. Topott holding infant son, Mrs. Alf Hall, and Mr. W. Topott stand in front of sod house. Dead birds hang in open door of shed. Two horses stand near barn.”

By October 1903, the town of Lloydminster consisted of two large stores, a post office, a telegraph office, a drugstore, a saddlery, a harness shop, two butcher shops, a blacksmith’s shop, a carpenter’s shop, three restaurants, a livery stable, and seventy-five houses.[13] That same month, however, the colony ceased to be all-British, as Clifford Sifton (then Minister of the Interior, and therefore in charge of immigration), had the reserve broken and opened the lands for homesteading to Canadian and American settlers. As a result, British colonists who arrived afterwards had to seek homesteads further from Lloydminster.[14]

The days of the settlement’s isolation came to an end on 27 July 1905, when the Canadian Northern Railway’s tracks finally reached them. According to one colonist, “the most beautiful music he ever heard was the whistle of that first approaching train. When the great locomotive appeared in sight, the Barr colonists sang and wept for joy.”[15]

Imagining Indigenous Neighbours

Although this has often been overlooked, some of the initial success of the colonists was also due to the assistance of Indigenous peoples. Evidently their presence had been an early concern for prospective colonists, as Barr devoted some space in his pamphlet to reassuring them that Indigenous peoples posed them no threat. Their neighbours would primarily be Europeans, Americans, and “Scotch servants of the Hudson’s Bay Company and their descendants, with a slight mixture of Indian blood, which only makes them the more interesting,” he wrote.

All Indians in the Northwest Canada are now practically civilized. They live on reservations, in houses of their own building, and farm the soil under government instructors, possessing in many cases, fine herds of cattle and horses. There are some reservations about 30 or 40 miles [48–64 kilometres] from our settlement, and I met many of their people and conversed with them. They are now quiet and law-abiding citizens. There are only about 20,000 scattered over the whole vast Northwest. There is nothing to fear from our Indian friends any more than from the gypsies of England.[16]

As with so much else that Barr wrote, this passage presented a simplistic and mistaken version of a much more complex reality, though in this case it also revealed a settler colonial mindset of superiority.

As scholars like Daniel Francis have noted, since their earliest interactions, Europeans had viewed Indigenous peoples through “a screen of their own prejudices and preconceptions.” One popular stereotype at the time was that Indigenous peoples were “frightful and bloodthirsty,” which perhaps explains Barr’s early attempts to reassure colonists that they had nothing to fear.[17] These efforts were not entirely successful: many of the colonists came to Canada heavily armed. In fact, once they were established in the tent city, the wealthier colonists passed the time comparing firearms, to the point that the press commented on it and surmised that they were preparing for battle with Indigenous peoples.[18]

Lloyd, through his involvement in the North-West Resistance/Rebellion some two decades prior, was familiar with one Indigenous strategy of resistance to settler encroachment, which was armed conflict. Since that time, however, the Cree people of the territory had shifted to a strategy of treaty-making, co-existence, and economic exchange, although the federal government continued their attempts at the coercive assimilation of all Indigenous peoples.

Relations Between the Cree and the Colonists

There were no such violent confrontations between the Cree and the Barr Colonists, at least none that have been recorded. Instead, the residents of Onion Lake Cree Nation forged religious, economic, and personal ties with the settlers. Nearly 80,000 feet of lumber was cut in the government-controlled sawmill on the reserve and sold to the Barr Colonists. Similarly, the settlement’s first church was built using logs supplied by their Cree neighbours, who transported them to Lloydminster and helped construct the building.[19]

In the early days before his departure, Barr sent a man to the reserve to buy supplies such as lumber, meat, and provisions for the stores. As previously mentioned, Indigenous freighters were hired to transport colonists and their goods to the land. Others were later hired by the colonists to make thatch roofs for their sod houses.[20]

The settlement’s first butcher, a Mr. Johnson, after processing two animals brought by Barr, did not know where he would find any more meat. An Indigenous man then led him to a herd of cattle, where he bought a steer and brought it back to his shop. Later, when that meat was gone, the pair set off to buy another. “So the supply was kept up,” Johnson recalled, “and soon I had built a little hut — our first butcher’s shop.”

As the colonists may have soon learned, Cree people at Onion Lake made their living not through agriculture but rather primarily through raising horses and cattle, though they supplemented this with income earned by freighting for the government, missionaries, and the HBC. Although Onion Lake had been a traditional meeting place for Indigenous peoples for centuries, and the wild onions for which it was named were a welcome addition to their diet in the spring, the land itself was not good for the purposes of farming. As government reports noted, the soil at the Onion Lake reserve was “too light for profitable cultivation” and many of their fields were “infested with noxious weeds” that had been inadvertently introduced with seed grain.[21]

Some Cree men guided the newly-arrived British hunters unfamiliar with the territory, and other Indigenous peoples taught some colonists how to trap and sold moccasins to those who realized their thin English boots would not keep them warm enough. Sometimes the colonists were able to offer help to Indigenous peoples too, such as when Ethel Sanderson’s family gave shelter to a man named Damas Laundry one cold winter night (he repaid them two days later with the gift of a deer).[22]

Clearly, early assessments that the colonists had “little to no contact with Indigenous people” are mistaken. However, a lack of sources prevents historians from painting a more precise picture of the relationship between the two, as the colonists in particular did not spend much time reflecting on these religious, commercial, and personal ties. An analysis of the Barr Colony’s female diarists, for instance, suggests that they were curious about Indigenous peoples but that when they wrote about their interactions, they portrayed themselves as “civilizers.” Such accounts are further marked by “a conspicuous absence of any consideration of the negative impact that Europeans had.”[23]

Nearby Residential Schools

At a broader level, though, it is important to note the federal government’s divergent approaches to these cultural groups. At the same time that the government was giving the Barr Colony active support in its attempt to construct a settlement based on English ethnicity, they were also waging a harsh and sustained effort to assimilate Indigenous peoples into English or French cultures. At nearby Onion Lake, two residential schools were competing for students, one Anglican and one Catholic. The Anglican clergyman responsible for the school, John Matheson, was fluent in English, French, Gaelic, and Cree, and his presence ensured that children were taught to “read and write both Cree and English.”[24]

However, the school undoubtedly did not remain bilingual after Matheson’s death in 1916, and the Catholic school taught only English from the outset. As early as 1897, the Catholic principal noted that all the pupils spoke English, even “to their parents, who do not understand what they say.” This language policy “not only disrupted the long-term transmission of Aboriginal culture, but [had] an immediate and destructive impact on the bonds of family.”

Cree artist Allen Sapp, a student who attended one of the schools during a later period, recalled: “No one ever abused me physically or sexually” (as was common in other schools) “but the way we were disciplined was not like home. We were forbidden to speak Cree—the teachers and everyone connected to the school spoke English—but Cree was the only language I knew. If we were caught speaking Cree to one another we would be punished.” Parents complained of such practices, which included the twisting of students’ ears; the Indian agent was instructed to discontinue that specific punishment.[25] Further, one historian has uncovered two instances of sexual abuse, one of which occurred during the 1940s. In one case, the perpetrator was fired, in the other, the student was sent home.[26]

Parents repeatedly refused to send their children to the schools on account of the way pupils were treated. Yet in at least one case, a family had their rations withheld as a result of their refusal. Hunger and poverty were often the reason that some parents ended up sending their children to schools, despite their concerns.[27] Exacerbated by malnutrition – in the 1920s, one student reported that he was always hungry and that seven students had run away because they too were always hungry – some students contracted diseases at the schools and their parents were not kept adequately informed of their health.[28]

In 1901, the Catholic school had an outbreak of measles, and in 1918 eleven pupils died from influenza at the Catholic school and one at the Anglican school. The following spring, chief and council “petitioned to hold a Sun Dance to commemorate the end of the First World War and the influenza pandemic. The request was denied but the band members attempted to hold it anyway, only to have the police appear and disperse the people who had gathered for the occasion.”[29]

This was a far cry from Lloydminster, where the police officers attended and partook in community events. At the first Christmas party the British colonists celebrated, a procession of NWMP officers carried in a “huge plum cake.” Likewise, the officers chaperoned the New Year’s Eve festivities as the colonists danced “on moccasined feet.”[30]

Comparable Group Settlements

The establishment of the Barr Colony sits firmly in the context of the broader project of British settler colonialism in Canada. Their settlement was only possible due to Indigenous dispossession, formalized by Treaty 6. In terms of other group settlements, however, Eric Holmgren argues that it is “almost impossible to compare Barr’s scheme to any other for no two were exactly alike.”[31] While block settlements are often referred to as a singular phenomenon, group settlement in fact took many forms. These include settlements created by federal government colonization programs, those formed by the colonists themselves, and those created by broader sociological or political shifts.[32]

The Barr Colony was unlike other major group settlements of the era. The Doukhobors, for instance, were a religious group who were persecuted for their beliefs in Russia. The immigration of over 8,000 members of this sect to Canada from 1899-1902 was financially assisted by the Canadian government, who also assisted their settlement by offering them accommodations for their communal and pacifistic traditions.[33] The Barr Colonists, however, were not a religious-sponsored settlement (despite being led by clergy), nor was the movement officially government-sponsored (despite being essentially bailed out by the government).[34]

As an attempted all-British settlement, however, the Barr Colony was not without precedent and can fruitfully be placed in the context of other such schemes, such as Cannington Manor. This village, founded in 1881 in what later became Saskatchewan, was sponsored by a group of English businessmen who intended it to be a commercial hub. Instead it became well-known for the activities of the group of upper-middle-class Britons who migrated there and attempted to completely replicate the culture of their home country. Most notorious were the three Beckton brothers, who constructed a racing stable and a large stone residence modeled on a traditional English country home. They proceeded to put on race days, tennis parties, fox hunts, dances, and evenings of music. Much as the Barr Colony did not remain British for long, and was joined by Canadian and American farmers, researchers have since pointed out that this group of flamboyant English people formed only a portion of the Cannington settlement: others came from Ontario, Manitoba, and the Maritime Provinces, were often lower-middle and working-class, and were in fact responsible for constructing many of the “English” buildings at the site. Although the village experienced some growth for the first nine years, low wheat prices combined with difficult growing conditions, as well as their lack of a railroad connection, led to a steady closure of businesses and outmigration of residents. Those who remained, however, found their fortunes reversed by the economic upswing of the early twentieth century.[35]

By contrast, the Barr Colony got off to rough start, primarily due to the unplanned and large number of colonists, their overall inexperience with farming, the unrealistic timeline, a combination of Barr’s inability to delegate, his lack of financial backing and his resultant failure to implement plans, plus the remote location. Despite these significant drawbacks, the colony survived and quickly became quite successful, no doubt due to the relatively high amount of capital the group possessed, the assistance provided by the federal government, the help of neighbours (Indigenous and settler alike), the colonists’ cooperative approach, the hard work and perseverance of those settlers who remained, and the relatively rapid connection to a railway.[36]

Conclusion: Legacies of Colonialism

After Lloyd departed the colony, he went on to become one of Canada’s most outspoken and notorious nativists: in the summer of 1928 alone he sent an estimated 27,000 letters denouncing Canadian immigration policy, many of which were printed in newspapers across the country and in periodicals published by organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan, the Empire Club, the Orange Order, the United Farmers of Canada, and the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire. As his biographer puts it: “Although there is no quantifiable method with which to assess the degree of Lloyd’s impact, it is clear that he affected the public’s attitude towards ‘foreign’ immigration. His letters … helped fuel anti-immigrant sentiment during 1928 and early 1929, and promoted the general atmosphere of fear later capitalized on by groups like the Ku Klux Klan and the Orange Order.” He adds that Lloyd influenced changes at both the provincial and national levels.[37]

The insulting language he used – he referred to “dirty, ignorant, garlic-smelling Continentals” and the “mongrelization” of Canada – reflected the attitudes held by many Canadians. Yet some Canadians objected to his campaign of discrimination, which helped rally them to the defense of non-British immigrants. For example, Lloyd’s letter-writing spree inspired translator Watson Kirkconnell to pen an article in support of continental European immigrants, and similarly inspired Canadian National Railways official Robert England to publish his own book on the subject.[38]

In 1931, acting on his doctor’s advice, Lloyd retired and moved to Victoria, British Columbia. Even in retirement, however, he continued to write letters to government officials - including the Prime Minister - calling for immigration to be restricted to people from England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, Norway, Iceland, Denmark, and Sweden. A nativist to the end, he died on 8 December 1940.[39]

Barr, by contrast, was caught up in one last settlement scheme before he died. In January 1910, he received a pamphlet advertising the “Closer Settlement” in Australia, where an area had been broken up into seventy-five acre farms that were available for immigrants. Although perhaps he wished to travel with a group, and founded the “American-Australia Settlement and Tourist Club” to that end, when he sailed for Australia that December, he did so not as a leader but as a colonist with only his wife and children for company (in 1903 he had married Christina Helberg, the young woman – thirty-five years his junior – who had been the secretary at the London office and who had traveled with him to Canada).

After his arrival, and just like the colonists he had led to Canada, Barr felt that he had been misled and that the settlement did not live up to its promises. He died, in debt and in poor health on an unsuccessful farm, on 18 January 1937.[40] The colony that the two men founded fared better than either of them, despite its rocky beginnings: Lloydminster has steadily grown in population to the present day.

- “Arrival of Barr Colonists,” Saskatoon Phenix [sic] (24 April 1903), 1, quoted in Oliver, “Coming of the Barr Colonists,” 69. Another portion of the speech is quoted in McCormick, Lloydminster, 41.↩

- Reid, All Silent, All Damned, 72–80; and Bowen, Muddling Through, 101–2, both citing F. Ivan Crossley, My Life and Experiences with the Barr Colony (Winnipeg: Western Producer, 1968). He further recounts the story of Jack selling at least one colonist a pair of blind horses. Jack also reportedly traded horses with another man while the latter was drunk and then refused to trade back, leading the man to take a shot at him.↩

- Bowen, Muddling Through, 104–6.↩

- The sources refer to “Indian” and “Metis” freighters, but in all likelihood the majority of the group were Cree freighters from the Onion Lake reserve.↩

- Reid, All Silent, All Damned, 83–4; Clive Tallant, “The Break With Barr: An Episode in the History of the Barr Colony,” Saskatchewan History 7, no. 2 (1954), 42; Rasmussen, “Empire, Identity, and the Britannia Colony,” 28 and 41; and Bowen, Muddling Through, 134–5. A vivid account of the voyage can be found in McCormick, Lloydminster, 42–52.↩

- McCormick, writing in 1934, reported that a little over 1,200 continued from Saskatoon to the settlement. Kathryn Ivany, “The History of the Barr Colonists as an Ethnic Experience: 1903-1928” (MA thesis, University of Alberta, 1964), 50–1, suggests that around 200 of the original colonists turned back. Bowen, Muddling Through, 182, cites Speers’ report of October 1903 in which he claimed to have accounted for 1,600 of the colonists. Oliver, “Coming of the Barr Colonist,” 74, reported that 320 found work in Manitoba, and that others remained at Regina, Moose Jaw, Dundurn, and Saskatoon. On those who went to find work later, see Bowen, Muddling Through, 176–8.↩

- Reid, All Silent, All Damned, 68; Bowen, Muddling Through, 188; and Clive Tallant, “The North-West Mounted Police and the Barr Colony,” Saskatchewan History 7, no. 2 (1954): 41–6.↩

- Holmgren, “Barr and the Britannia Colony,” 129; and Bowen, Muddling Through, 68. While historians have not remarked on the Messianic overtones of this administrative arrangement, these were not lost on the colonists and the dozen became “irreverently known as Lloyd’s apostles.” Quote in A.N. Wetton, “On Lloyd Trail With Barr, Canon English Reminisces,” Saskatoon Star-Phoenix (22 September 1949), 5.↩

- Kitzan, “Fighting Bishop,” 19; see also Reid, All Silent, All Damned, 106–7. On the two factions, which came to encompass other, commercial issues, see Bowen, Muddling Through, 192–3. Although Lloyd held a somewhat puritanical stance on alcohol, its harmful effects in this context - such as exacerbating domestic violence – should not be overlooked; see for instance Rasmussen, “Empire, Identity, and the Britannia Colony,” 52–5.↩

- Kitzan, “Fighting Bishop,” 21. A nativist is defined as someone who favours existing citizens over immigrants and generally opposes further immigration. In this case, of course, this did not mean that Lloyd favoured the Indigenous inhabitants but rather the existing British settlers.↩

- McCormick, Lloydminster, 79.↩

- The Rendells are the most conspicuous example of the former; there is correspondence reproduced in Oliver, “Coming of the Barr Colonists,” 75–87 (the originals are no longer extant). A story of an inexperienced farmer making good is found in Arthur E. Copping, Golden Land: The True Story and Experiences of British Settlers in Canada (Toronto: Musson, 1911), 78–83; see also J.C. Hill, “How I Raised My $1,500 Oats,” MacLean’s (13 September 1913).↩

- Reid, All Silent, All Damned, 106.↩

- Ivany, “An Ethnic Experience,” 50–1.↩

- Holmgren, “Barr and the Britannia Colony,” 160; and Copping, Golden Land, 77. For some recollections of the colony’s early years, see Guy Lyle, Beyond My Expectation: A Personal Chronicle (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1981).↩

- Barr quoted in Reid, All Silent, All Damned, 52.↩

- Daniel Francis, The Imaginary Indian: The Image of the Indian in Canadian Culture (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 1992), 7–8. See also J.R. Miller, Skyscrapers Hide the Heavens: A History of Native-Newcomer Relations in Canada, 4th ed. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018), esp. chapter four.↩

- Reid, All Silent, All Damned, 62, 68–9, 73, and 82; and Foster, “The Barr Colonists,” 89.↩

- The lumber was intended to be shipped to the settlement site in time for the colonists’ arrival but the Saskatchewan River was flowing too swiftly to allow the shipment, adding to the colonists’ difficulties. Holmgren, “Barr and the Britannia Colony,” 131 and 148–9; Reid, All Silent, All Damned, 107; Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs (1903), 237; and T.C.B. Boon, The Anglican Church from the Bay to the Rockies: A History of the Ecclesiastical Province of Rupert’s Land and its Dioceses from 1820 to 1950 (Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1962), 292–3.↩

- On the roofs, see Bowen, Muddling Through, 171; and on the supply run, see Reid, All Silent, All Damned, 94 and 105. McCormick noted that Indigenous peoples were present for the first Dominion Day celebrations in Lloydminster, though he provides little detail. McCormick was also present for the Sun Dance, an Indigenous ceremony, at nearby Frog Lake; however, it is unclear if he was invited or welcomed and his account is markedly derogatory. See McCormick, Lloydminster, 79 and 179–91.↩

- See the Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs (1903), 202; and Marceau-Kozicki, “Onion Lake Indian Residential Schools,” 20–1.↩

- See Arthur E. Copping, Golden Land: The True Story and Experiences of British Settlers in Canada (1911), 74–75 (the butcher) and 123 (guides). The story of Damas Laundry is found in Rasmussen, “Empire, Identity, and the Britannia Colony,” 113–14; and the remaining information comes from Bowen, Muddling Through, 183.↩

- Franklin Foster, “Settlement,” Lloydminster.net (n.d.); and Rasmussen, “Empire, Identity, and the Britannia Colony,” 114. However, positive steps have been taken in recent years; see for instance Ezzah Bashir, “Lloydminster Comes Together to Sign Hearty of Treaty Six Reconciliation,” My Lloydminster Now (18 April 2018).↩

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), Canada’s Residential Schools: The History, Part 1, Origins to 1939, vol. 1 of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press for the TRC), 622, 715.↩

- Accounts from survivors of these schools can be found here and here; quotes are from TRC, Canada’s Residential Schools, 1:622, 624; the account regarding corporal punishment is found at 524.↩

- Marceau-Kozicki, “Onion Lake Indian Residential Schools,” 189–9.↩

- TRC, Canada’s Residential Schools, 1:264, 267, 281.↩

- TRC, Canada’s Residential Schools, 1:507–8. Decades later, in the mid-1960s, students at one of the schools were subjected to a medical experiment into the efficacy of an amebicide (a drug that kills amoeba). See TRC, Canada’s Residential Schools, 1:229. On malnutrition in residential schools, see Ian Mosby and Tracey Galloway, “The Abiding Condition was Hunger’: Assessing the Long-Term Biological and Health Effects of Malnutrition and Hunger in Canada’s Residential Schools,” British Journal of Canadian Studies 30, no. 2 (2017): 147–62; Mosby and Galloway, “‘Hunger Was Never Absent’: How Residential School Diets Shaped Current Patterns of Diabetes Among Indigenous Peoples in Canada,” CMAJ 189, no. 32 (14 August 2017); and, on experimentation, Mosby, “Administering Colonial Science: Nutrition Research and Human Biomedical Experimentation in Aboriginal Communities and Residential Schools, 1942-52,” Histoire sociale/Social History 46, no. 1 (2013): 145–72.↩

- TRC, Canada’s Residential Schools, 1:440, 442. A later case of smallpox was treated inadequately, and another student died of tuberculosis; his mother subsequently refused to send her daughter to the school (443, 444). Perhaps indicative of their feeling towards the institution, one or two students deliberately set fire to the Anglican school in 1928 (483, 486).↩

- Bowen, Muddling Through, 189–90.↩

- Holmgren, “Barr and the Britannia Colony,” 12.↩

- Anderson, “Ethnic Bloc Settlements.”↩

- See Julie Rak and George Woodcock, “Doukhobors,” Canadian Encyclopedia (26 February 2019).↩

- Despite this, other scholars have – perhaps mistakenly – placed the Barr colony firmly in the context of the colonial missionary movement; see for instance Carey, God’s Empire, esp. 366–70.↩

- This synopsis is based upon Kristin M. Enns-Kavanagh, “Cannington Manor, an Early Settlement Community in Southeastern Saskatchewan” (MA thesis, University of Saskatchewan, 2002).↩

- On the scheme’s flaws, see Reid, All Silent, All Damned, 126–43. The involvement of the government is detailed in Holmgren, “Barr and the Britannia Colony,” while the involvement of the NWMP is discussed in Tallant, “Mounted Police and the Barr Colony.” On the capital the colonists possessed, see Ivany, “An Ethnic Experience,” 59; and Reid, All Silent, All Damned, 70 and 79; and, on the various cooperative arrangements, see Ivany, “An Ethnic Experience,” 5.↩

- Kitzan, “Fighting Bishop,” 80, 103–4, and 134.↩

- Kitzan, “Fighting Bishop,” 160–2. See also Watson Kirkconnell, “Western Immigration,” Canadian Forum (July 1928): 706–7; and Robert England, The Central European Immigrant in Canada (Toronto: Macmillan, 1929); both of which are discussed in Daniel R. Meister, The Racial Mosaic: A Pre-history of Canadian Multiculturalism (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2021), chaps. 1–2.↩

- Kitzan, “Fighting Bishop,” 82 and 86.↩

- Reid, All Silent, All Damned, 114–23↩