By Steven Schwinghamer, Historian

Terminology

The terminology of this paper is difficult in a few ways. It is sometimes hurtful to encounter archaic slurs and stereotypes about race and sexual orientation—and some of those are presented as part of this research. I use “queer” occasionally as shorthand for the 2SLGBTQIA+ community, very advisedly: I am reminded that many of my friends would have experienced that term as abusive before it was reclaimed. I use “homosexual” where it matches historical use, such as in connection with legislation. The term was sometimes used at this time to represent a larger idea of “sexual aberration.” Finally, I use heterosexism to refer to an ideological prejudice against non-heterosexual people, often founded on the assumption that only heterosexuality is normal or natural.

Introduction

In 1952, the Canadian government adopted a new immigration act that gave significant authority regarding admission and refusal to the Cabinet and the Minister of Immigration. This authority could operate based on anything from nationality to “probable inability to become readily assimilated” or “peculiar customs, habits, modes of life or methods of holding property.”[1] The act also expanded the prohibited classes of immigrants, including for the first time a direct mention of “homosexuals.”

The explicit heterosexist prohibition remained in the immigration act for more than twenty years, ending when a new act came into force in 1978. There was a contentious, moralizing environment within the immigration branch that both propelled and challenged regulating immigration based on sexual orientation.

As 2SLGBTQIA+ people around the world confront escalating assaults (including the stripping away of their rights), the historical context of these discriminatory policies, and their legacies into the present, are of renewed importance.

Context

Canadian state discrimination against queer people during this post-war period has been convincingly linked to Cold War security concerns by sociologists Gary Kinsman and Patrizia Gentile.[2] Historian Philip Girard summarizes the paranoid environment that demanded rigid conformity: “[a]ny kind of deviance might now be suspect, because it represented an independence of mind that could no longer be tolerated.”[3] These deviations were also understood to be potential points of vulnerability for citizens. Exposure as a homosexual, for instance, could be a pressure used to blackmail a person. Heterosexist and anti-Communist ideologies reinforced each other in a circular justification for discriminatory exclusion.

In the area of immigration, security concerns were reflected by the increasing power of the RCMP, which took on overseas screening of potential immigrants. Pigeon-holing a person as a member of a “group” and then naming that group as a security issue was no small threat in postwar Canada: from November 1946 through March 1948 (even before the new act), 29,671 applicants for immigration to Canada were rejected on security grounds.[4]

Along with this framing of undesirability, sexualities deemed deviant from the heterosexual norm were pathologized and further criminalized. In 1948, the Canadian Criminal Code was amended to add the possibility of indefinite detention for “criminal sexual psychopaths,” triggered for review by certain offenses. Buggery and gross indecency, both common charges used to prosecute intimacy between men, were potential triggers.[5] In 1961, this was altered to “dangerous sexual offender” to remove the medical aspect of determining psychopathy.[6] This approach made it easier to use the “dangerous sexual offender” process.[7]

These pieces of context are certainly important, but they do invite us to overlook the role of the immigration branch itself in excluding homosexuals. For instance, Girard, who locates the responsibility for the above changes firmly with the RCMP based on security, does so partly on the strength of his estimation of the senior civil servants in immigration at this time as “liberal, humanistic individuals.”[8] This sits at odds with internal correspondence and practices related to race, religion, and more: at that time, the immigration branch had its share of bigoted people in influential positions.

For instance, in 1955, Director of Immigration C.E.S. Smith wrote a memorandum for Deputy Minister Laval Fortier entitled “A Review of Immigration from the British West Indies.” The memo states that “it has long been the policy of this Department to restrict the admission to Canada of coloured or partly coloured persons” and argues that

it is from experience, generally speaking, that coloured people in the present state of the white man’s thinking are not a tangible community asset…they do not assimilate readily and pretty much vegetate to a low standard of living…many cannot adapt themselves to our climatic conditions.[9]

Plainly, the immigration department of the 1950s and 1960s could and did originate and sustain exclusionary policies based on discriminatory views of race, religion, and other characteristics, making claims of their liberal character tenuous. As we will see, some immigration officials supported the prohibition of immigrants based on sexual orientation.

Security or Morality?

The immigration branch of the 1950s, like Canadian society around it, was heteronormative and heterosexist. Within immigration policy circles, this was expressed in the realm of morality rather than security. This was clear during the process to update Canadian immigration legislation after the Second World War. On the matter of heterosexism, immigration regulations as summarized in 1947 did not include any reference to homosexuality.[10] However, a heavily marked-up draft from late 1950 reflects “homosexuals” and “lesbians” being added to the prohibited classes in two different handwritten notations.[11]

There was some specific resistance to the proposed prohibition of homosexuals, notably from Roger G. Robertson, the Clerk of the Privy Council. Robertson argued that “homosexual” was too general for a statute as it could “cover persons who a psychiatrist would claim have homosexual tendencies but who may, even, be entirely unaware of it themselves.”[12] Nevertheless, the language survived in the eventual 1952 act as a specific bar against “homosexuals” as well as persons “living on the avails of...homosexualism,” and persons “who attempt to bring into Canada or procure prostitutes or other persons for the purpose of...homosexualism.”[13]

The immigration department had a great deal of experience in structuring and obscuring exclusions of specific groups, from the “continuous journey” regulations through anti-Black “climatic unsuitability” and more. It is therefore of some note that the department took the step of openly listing homosexuals, and listing them in the section with prostitutes, pimps, and so on. Rather than arguing that homosexuals were vulnerable to subversion by ideological enemies, the barrier was presented in a subsection of the prohibited classes dealing with immorality. This reinforces that the bar was really linked to heterosexist ideology (as others were linked to racist ideology, for instance), and not to security concerns. Further, while security-related grounds were laid out in some detail in internal discussions about revisions to the immigration act, the question of a person’s sexuality was not addressed in them, and the other “moral” additions to the prohibited classes, such as of drug traffickers, do not appear either.[14]

A significant review of security screening and appeals in the immigration process was conducted in 1958. Throughout the resulting report, there is a clear distinction between the mainly anti-Communist security provisions and the prohibition based on sexual orientation. Sexual orientation was an aspect of the RCMP’s investigation for “Stage B” or overseas clearance of an immigrant. If a reason for refusal related to security concerns turned up—such as if someone had collaborated with enemy forces in time of war—details would not be made available to immigration officers. Nor could there be an appeal. However, in the case of “moral” objections, such as “sexual aberration” or suspected criminality, the information could be disclosed to both the immigration officers and the applicant, specifically with a view towards a potential appeal.[15]

Exclusionary Practice

Distancing the policy of prohibition against homosexuals from security considerations does not mean it was weaker in practice. During the period of explicit exclusion of homosexuals, the immigration branch received and pursued intelligence on targeted visitors and immigrants from its own intelligence resources and from police forces across the country, even to the extent of keeping tabs on those convicted of related offenses such as circulating homosexual literature and pornography.[16] It is not clear that these offenses of themselves would have placed an immigrant in danger of deportation, but convictions for other kinds of offences used to directly prosecute homosexuality—gross indecency, committing obscene acts, or lewdness, for instance—did lead to monitoring and sometimes to deportation.[17]

The divide between the cultural climate of increasing acceptance for queer people and the language of the immigration act made for an enforcement challenge, notably at the land boundary at Windsor-Detroit. Through the 1960s and into the ‘70s, visitors to gay clubs were open and visible as they crossed the international border. In September of 1975, an immigration officer asserted that “homosexuals today are not only unashamed but are inclined to parade their intentions proudly and readily admit being homosexuals and thus prohibited.” In response, they were directed that where someone admits to being or has been convicted of being a homosexual, the immigration act should be applied (meaning denial of entry).[18]

The challenge at the border opened an exchange in the department. About two months later, a series of memos circulated from the Acting Director General of the Facilitation, Enforcement and Control Branch, regarding admission of homosexual applicants. He acknowledges that the duty of department was “to implement whatever legislation is in existence.” The memo, however, went on to lay out a compromise as a way forward for the department, noting that existing legislation did not

impose the duty to go to extraordinary lengths to discover prohibitions, especially when such an exercise would create inequities and would appear discriminatory…the applicability of paragraph 5(e) cannot be determined merely from manner, dress or association with known homosexuals. To question a person concerning homosexuality because he appears effeminate would be accepting an erroneous premise as would be the questioning of a person concerning the use of drugs solely because he wears his hair long.[19]

This was no real solution for prohibition under the act; as discussed above, gaining entry by concealing a factor that could trigger exclusion merely left a person in a vulnerable, precarious state once within Canada. That vulnerability extended beyond immigration status. In the 1960s—and for decades after—being suspected of homosexuality in Canada could stir up formal investigations, trigger ostracization, and end a career. In 1964, a civil servant died of a heart attack during RCMP interrogation about his sexuality, part of the LGBT Purge from the ranks of the public service.[20] This social and professional pressure forced targeted people to protect themselves. Hiding was common, but as the concept of gay liberation took hold, some immigrants braved the consequences of being out, out loud. Lezlie Lee Kam came to Canada in 1970 from the Caribbean, just after finishing high school, to join her mother in Toronto. In 1976, as she started work, she recalls having to act to get ahead of prejudice:

I had to come out, because comments were being made about me being “one of those.” You know, “She’s a butch, she’s a lesbian”…I said, “I’m hearing comments being made about me to my face and behind my back. You look at my evaluations about how I’m doing my job, and if anything happens and I lose my job, there’s going to be hell to pay.” So, I outed myself to keep myself safe.[21]

Kam eventually took up her Canadian citizenship to protect herself from deportation as she was an activist and protested discrimination against queer people, which included police action based on stereotypes and bigoted assumptions:

…the police would raid our place, loot the house that we were in, looking for underaged girls, because they deemed us to be pedophiles. Yes. That we were preying on these young girls. So, we started protesting outside the police station. And I was told that I could be deported if I continued protesting. Not the white women who were also protesting, but me. So, I had to carry my little slip of paper with me. So, the more (laughs) the more vocal I became, the more I was in jeopardy, so I immediately got my Canadian citizenship.[22]

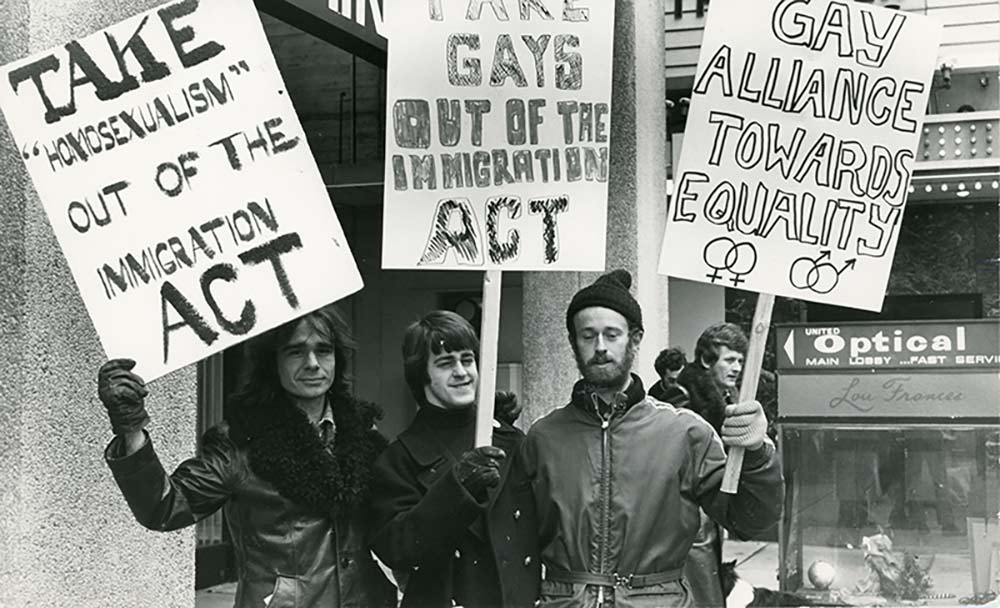

Credit: Arquives 1990-002/07P

Lifting the Prohibition

The 1966 White Paper on Immigration stated that “the homosexual, the professional beggar or vagrant, and the chronic alcoholic” were “not particularly desirable as immigrant or non-immigrants” but also were “not true dangers to the national interest by virtue simply of their personal failings…they therefore could safely be deleted from the specific list of prohibited persons.”[23] This policy direction reflected a shifting mood in Canada through the 1960s which was famously expressed by then-Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau: “there’s no place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation.”[24] He was summarizing the 1969 overhaul of Canada’s Criminal Code, which included an exception to two of the offences typically used to prosecute gay people (buggery and acts of gross indecency) if between a husband and wife or to any two people over the age of 21, provided the acts were consensual.[25]

Although the regulatory change was welcome, there is a fraught background. Just two years before, the Supreme Court of Canada declined to hear the appeal of a homosexual man convicted of gross indecency for private, consensual acts with another adult, leaving him with a life sentence.[26] Following the White Paper and the Criminal Code update, a 1970 outline of proposals for the new immigration legislation carried forward this clear direction, stating that the sections “dealing with immorality, would be modified by deleting reference to homosexuals and homosexualism.”[27]

The disagreements between legislation, public attitudes, and political will resulted in some public tests of the heterosexist practices of the immigration branch. In 1974, a gay American man, John Kyper, was ordered deported from Canada. His case provoked public complaints and press coverage, including comment from John Moldenauer, an activist for gay rights in Toronto. Moldenauer was quoted in the Canadian Press, stating that public officials had given assurances that “the law is not applied against gay people, but we know that it is.”[28] Indeed, Kyper’s deportation order clearly specified his homosexuality as the cause for his removal.[29] Another case, that of Clifford Wynn, had created some publicity in 1971 and was finally addressed in 1974 with advice that, while the deportation based on his homosexuality was correct, Mr. Wynn would be granted discretionary landing by the Immigration Appeal Board.[30]

In the shifting legal climate, convictions—domestic or abroad—related to a person’s sexual orientation were problematic for immigration officials. A 1974 draft advisory memorandum to Robert Andras, the Minister of Employment and Immigration, indicated that removing homosexuals from the prohibited classes “will not relieve us of certain problems” as potential immigrants might carry past convictions related to homosexual acts. While Canadian authorities might seek to exempt convictions for acts that would no longer be criminal in Canada, the draft drily noted the possibility of “difficulty in certain instances in obtaining factual details of past criminal convictions in this area.”[31] In September of 1974, as the department dealt with public fallout from the Kyper case, Deputy Minister A.E. Gotlieb advised the Minister that:

there are other parts of Section 5 which are out of date and which we intend to correct with a new Immigration Act following the publication of the Green Paper. For example, there is the blanket prohibition against alcoholics, which makes no more sense than the prohibition against homosexuals; there are also the prohibitions against idiots, imbeciles, and morons, terms which have no clear meaning either from a medical or legal point of view…For every dubious prohibition in the Immigration Act there is a lobby group both in and out of the House, that would like to engage in a full-scale debate of their favourite issues.[32]

Senior officials in the department advised that where homosexuality was the only grounds for a person being prohibited, a Minister’s permit might be considered.[33] It seems that even before the prohibition was formally lifted, the department established a pathway for admission for people who were rejected based on sexual orientation or gender identity. However, it must be noted that Ministerial permits were hardly a certainty, and generally some exceptional indication was expected to justify overriding the Act.

While the department was moving away from prohibiting homosexuals in practice, there was substantial resistance. An exchange between two very senior bureaucrats in the immigration branch (one in charge of admissions, the other in charge of operations in Canada) highlights opposition to “the Deputy [Minister]’s desire to remove Section 5(e) from the prohibited classes without maintaining some kind of protection for Canadians against alien child molesters.”[34] The Chief of Admissions goes on to point out that after several years with virtually no deportation cases involving homosexuals, there have been several high profile cases of pedophile immigrants or applicants in 1974—implying that the public discussion of weakening the prohibition was inviting an undesirable class to enter the country.

The solution that was recommended was to assume that “the normal (pardon the word) homosexual applying for admission to Canada would not be found out nor would he be questioned in this area.”[35] In immigration terms, this was no solution at all: a queer person could still be refused at examination and could be deported later for misrepresentation if their sexual orientation became known. The senior civil servants in immigration understood these details well and would have understood their solution as belonging within Canada’s long tradition of coded and obscured admissibility criteria. This “solution” would have retained language that could be weaponized to exclude at need, while the department might point to more open practices if criticized.

Regional Directors met after the Kyper case and resolved “that a ‘common sense’ approach should be used in the administration of those sections of the Act which are outdated.”[36] In 1976, the Minister of Immigration indicated to cabinet that the committee struck to consider the new policy and legislation governing immigration offered specific advice regarding homosexuals, stating:

A majority of the Committee recommends that the present prohibition against homosexuals should be repealed. Such a prohibition is difficult to administer and – particularly since the decriminalization of homosexual conduct between consenting adults – has generated considerable resentment on the part of a group which feels that it has been the subject of unjustifiable discrimination. I concur with the Committee’s majority position that the new Act should not prohibit homosexuals.[37]

This reflected the public mood: indeed, the public advice via the Special Joint Committee of the Senate and the House of Commons on Immigration included responses from gay rights groups in all ten provinces, including the Association homophile de Montréal. The association’s President, Roger Bellemare, located the exclusion firmly in heterosexist moralizing, telling the committee that “the repression of a non-criminal behavior in Canadians constitutes a basic injustice towards immigrants who are homosexuals. The state cannot be a censor of private morality.”[38] Philip Girard summarizes the successful intervention by community organizations in the revision of immigration policy as “the first occasion on which the gay community had participated in the mainstream political process.”[39]

Conclusion

In 1952, the Canadian federal government revised the immigration act to exclude immigrants based on sexual orientation. Evidence shows us that the opinions and morals of officials within the immigration branch were key to this prohibition. Although refusing “homosexuals” was quickly understood to be problematic and out of step with the social and cultural environment of Canada—and even its other laws—the bar remained in place until the new immigration act took effect in 1978.

Acknowledgements

The research for this project was possible thanks to an agreement between the Canadian Museum of Immigration and the Research and Evaluation unit of Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada that includes access to restricted files. A presentation of a more complete report on this research, hosted by IRCC, can be viewed at https://gccollab.ca/file/download/20218908.

- Library and Archives Canada. Statutes of Canada. An Act Respecting Immigration, 1952. Ottawa: SC 1 Elizabeth II, Chapter 42. section 61(g).↩

- Gary Kinsman and Patrizia Gentile, The Canadian War on Queers: National Security as Sexual Regulation, Sexuality Studies Series (Vancouver, B.C: UBC Press, 2010), 44.↩

- Philip Girard, “From Subversion to Liberation: Homosexuals and the Immigration Act, 1952-1977,” Canadian Journal of Law and Society 2:1 (1987), 3.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, RG 76-B-2, Immigration Branch fonds, Vol 948, File SF-C-1-1, “Cabinet Decisions on Immigration Policy,” Part 2, Memorandum to Cabinet: Immigration Policy and Procedures, 10 May 1958, Appendix C, Report of the RCMP on Security Screening of Immigrants, page 2↩

- Gary Kinsman and Patrizia Gentile, The Canadian War on Queers: National Security as Sexual Regulation↩

- Kinsman and Gentile, Canadian War on Queers, 73.↩

- Valerie Korinek, Prairie Fairies: A History of Queer Communities and People in Western Canada, 1930-1985 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018), 104.↩

- Girard, 8.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, RG 26, Department of Citizenship and Immigration fonds, Vol 124, File 3-33-6, “Immigration from British West Indies – Admission from and Admission of Coloured or Partly Coloured Persons,” Director to Deputy Minister, Ottawa ON, 14 Jan 1955↩

- Library and Archives Canada, RG 26-A-1-c, Department of Citizenship and Immigration fonds, Vol 97, File 3-15-1, “Canadian Immigration Act and Regulations – Amendments,” Part 1, Immigration Branch, “Regulations Re Immigration to Canada,” 1 November 1947, page 6↩

- Library and Archives Canada, RG 26-A-1-c, Department of Citizenship and Immigration fonds, Vol 97, File 3-15-1, “Canadian Immigration Act and Regulations – Amendments,”, Part 1, First Draft of the New Immigration Act, attached to Memorandum – meeting to discuss the First Draft of the New Immigration Act, 15 December 1950. Page 5, sections 3 (h) and (i) of draft, reflects changes to encompass, among others, homosexuals and male prostitutes.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, RG 26-A-1-c, Department of Citizenship and Immigration fonds, Vol 97, File 3-15-1, “The Immigration Bill (annotated), Laval Fortier,” Part 3, Memorandum “Points for consideration in the draft of the Immigration Bill,” R.G.R. (Roger G. Robertson), Privy Council Office, 24 March 1952, page 3↩

- Library and Archives Canada, RG 26-A-1-c, Department of Citizenship and Immigration fonds, Vol 97, File 3-15-1, “The Immigration Bill (annotated), Laval Fortier,” Part 3, sections 5(e) and (f). The notations included for Fortier, then the Director of Immigration, noted that those sections were amended from existing language specifically to include “homosexuals” but do not, unlike some other areas of notation, expand on reasons for this modification.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, RG 76-B-2, Immigration Branch fonds, Vol 948, File SF-C-1-1, “Cabinet Decisions on Immigration Policy,” Part 1, Walter Harris, Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, “Memorandum to the Cabinet,” Ottawa ON, 8 May 1951.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, RG76-B-2, Immigration Branch fonds, Vol 948, File SF-C-1-1, “Cabinet Decisions on Immigration Policy,” Part 2, “Memorandum to the Cabinet: Immigration Policy and Procedures,” Appendix E, pages 4-5, and Section II, page 5, Ottawa ON, 10 May 1958.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, RG 76, Immigration Branch fonds, Vol 1436, File 230-1, “Obscene Literature,” Detective Gerald Rice, Morality Division, Ottawa Police Department, to Detective / Sergeant William O’Driscoll, Criminal Intelligence Section, Ottawa ON, 11 January 1969.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, RG 76, Immigration Branch fonds, Vol 1404, File 200-1, “Prohibited Persons – General,” Part 1, C.A. Babcock, Officer-in-Charge, Toronto Intelligence Unit (Department of Manpower and Immigration) to Chief Intelligence Officer, Home Branch, Ottawa ON, 19 January 1968; Part 4, Detective Lieutenant Charles Ells-worth, Massachusetts State Police, to H.W. Vaughan, Chief Intelligence Officer, Canada Employment and Immigration, Halifax, Boston MA, 25 February 1980; Library and Archives Canada. RG 76, Immigration Branch fonds, Vol 1015, File 5000-14-6-2, “Legislation and Interpretation – Moral Turpitude,” Part 1, A.L. Campbell to W.J. Dickman, Ottawa ON, 7 September 1967.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, RG 76, Immigration Branch fonds, Vol 1169, File 5400-6-5, “Controversial, Undesirable or Prohibited Persons – Homosexuals,” Teletype from Director Immigration, Ontario Region, to Mr. J. St. Onge, Acting Director, General Facilitation, Enforcement and Control, Toronto ON, 17 September 1975.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, RG 76, Immigration Branch fonds, Vol 1169, File 5400-6-5, “Controversial, Undesirable or Prohibited Persons – Homosexuals,” Acting Director General, Facilitation, Enforcement and Control Branch, to Regional Directors of Immigration, Ottawa ON, 20 November 1975.↩

- Kinsman and Gentile, Canadian War on Queers, 95.↩

- Oral history with Lezlie Lee Kam, interviewed by Emily Burton, Halifax NS, 30 September 2016, CMI Collection (16.09.30LLK).↩

- Oral history with Lezlie Lee Kam.↩

- Library and Archives Canada. White Paper on Immigration, 1966, accessed at https://pier21.ca/research/immigration-history/white-paper-on-immigration-1966↩

- Pierre Elliott Trudeau, media interaction, 21 Feb 1967, accessed at: https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/1260871747995↩

- Library and Archives Canada, RG 76, Immigration Branch fonds, Vol 1169, File 5400-6-5, “Controversial, Undesirable or Prohibited Persons – Homosexuals,” Memorandum by Douglas J. Sleeman, Legal Services, 25 September 1974.↩

- Sidney Katz, “We’re society’s scapegoats: Homosexuals shocked by life term ruling,” Toronto Star, 11 November 1967.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, RG 76, Immigration Branch fonds, Vol 1169, File 5400-6-5, “Controversial, Undesirable or Prohibited Persons – Homosexuals,” Summary of Proposals for New Immigration Act Part E – Prohibited Classes,” 9 April 1970.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, RG 76, Immigration Branch fonds, Vol 1169, File 5400-6-5, “Controversial, Undesirable or Prohibited Persons – Homosexuals,” Canadian Press teletype, 21 September 1974.↩

- Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Historical Society, 2005-19, John Kyper Fonds, Box 2 Folder 10, Canada, Department of Manpower and Immigration, “Deportation Order Against John Stewart Kyper,” Whirlpool Bridge, Niagara Falls ON, 26 August 1974.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, RG 76, Immigration Branch fonds, Vol 1169, File 5400-6-5, “Controversial, Undesirable or Prohibited Persons – Homosexuals,” Memorandum, Homosexualism – Clifford Calvin Wynn – Position before the Board, from Deputy Minister A.E. Gotlieb to Minister of Immigration (Andras?), Ottawa ON, 5 November 1974.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, RG 76, Immigration Branch fonds, Vol 1169, File 5400-6-5, “Controversial, Undesirable or Prohibited Persons – Homosexuals,” draft memorandum, Homosexuals, Deputy Minister A.E. Gotlieb to the Minister, 24 March 1976, marked as not sent.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, RG 76, Immigration Branch fonds, Vol 1169, File 5400-6-5, “Controversial, Undesirable or Prohibited Persons – Homosexuals,” Memorandum to the Minister, Deputy Minister A.E. Gotlieb to the Minister of Immigration, Ottawa ON, 9 September 1974.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, RG 76, Immigration Branch fonds, Vol 1169, File 5400-6-5, “Controversial, Undesirable or Prohibited Persons – Homosexuals,” Memorandum, Homosexuals, from Acting Deputy Minister Jack L. Manion to the Minister of Immigration, Ottawa ON, 27 October 1975.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, RG 76, Immigration Branch fonds, Vol 1169, File 5400-6-5, “Controversial, Undesirable or Prohibited Persons – Homosexuals,” A/DG Home Branch FDC to Chief, Admissions Division TBS, 26 September 1974. The file also contains news coverage regarding pedophiles, such as Richard Lee, “Pedophilia: Delicate Cases Where Courts Tread Lightly,” 24 September 1974, p 37.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, RG 76, Immigration Branch fonds, Vol 1169, File 5400-6-5, “Controversial, Undesirable or Prohibited Persons – Homosexuals,” A/DG Home Branch FDC to Chief, Admissions Division TBS, 26 September 1974. Parenthetical remark on the use of the term “normal” is in the original.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, RG 76, Immigration Branch fonds, Vol 1169, File 5400-6-5, “Controversial, Undesirable or Prohibited Persons – Homosexuals,” Memorandum, Homosexuals, from Acting Deputy Minister Jack L. Manion to the Minister of Immigration, Ottawa ON, 27 October 1975.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, RG 76, Immigration Branch fonds, Vol 1169, File 5400-6-5, “Controversial, Undesirable or Prohibited Persons – Homosexuals,” Memorandum to Cabinet, Immigration: Preparation of New Policy and Legislation, p23-24, quoted in draft memorandum, Homosexuals, Deputy Minister A.E. Gotlieb to the Minister, 24 March 1976, marked as not sent.↩

- Canada, House of Commons, Minutes and Evidence the Joint Special Committee of the Senate and of the House of Commons on Immigration Policy, First Session, Thirtieth Parliament, 13 May 1975, Witness statement of Roger Bellemare, page 657.↩

- Girard, 16.↩