by Jan Raska, PhD, Historian

Introduction: Origins of World Refugee Year

In the spring of 1958, four young individuals affiliated with the Bow Group, a conservative public policy think tank inside the British Conservative Party, initially suggested the concept of an international year specifically focused on addressing the challenges faced by refugees. Timothy Raison, Christopher Chataway, Colin Jones, and Trevor Philpott advocated for the establishment of a World Refugee Year (WRY) and called on the United Kingdom to play a leading role in promoting it to its global allies. In light of the triumph of the UN International Geophysical Year the previous year, the four individuals proposed a year dedicated to a united endeavour to address the global refugee situation.

The WRY aimed to generate global awareness about the needs of refugees and to mobilize financial resources for organizations dedicated to enhancing their well-being and seeking durable solutions, including permanent resettlement. The WRY initiative operated under the supervision of the United Nations, specifically the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Middle East (UNRWA), and the Intergovernmental Committee for European Migration (ICEM), in collaboration with various national governments and local authorities.[1]

British officials introduce World Refugee Year before the United Nations

The proposal for the establishment of the WRY was introduced by British officials to the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) during its thirteenth session in 1958. The plan suggested that, depending on the specific requirements of each member state, WRY could serve as an effective mechanism for providing increased assistance to refugees worldwide.[2] The UNGA approved a resolution on 5 December 1958, adopting WRY with a significant majority of votes. Member states decided to raise awareness of the refugee situation and encouraged additional financial contributions from national governments, non-profit organizations, and private citizens.

The goal was to improve the situation of refugees and find long-term solutions to their plight, including voluntary return, resettlement, or integration. These options were to take into account the specific needs of each refugee and have their consent. The declaration of WRY as a “humanitarian year” sought to unite efforts in addressing a significant issue for the international community, namely the refugee crisis involving Europe’s postwar Displaced Persons (DP) camps, but also the Palestinian refugees in the Middle East, Algerian refugees in North Africa, and Chinese refugees in British Hong Kong. This issue required both financial and human resources, but also contributed to global instability and political tensions in some parts of the world. The WRY achieved significant recognition in the realm of global humanitarian activities, in large part because the plan extended aid to any refugee rather than adhere to the restrictive criteria of United Nations (UN) policies. This suggests that the ideological foundations underpinning WRY disregarded political and legal factors.[3]

United Nations and the Formation of National Committees for World Refugee Year

The member states of the United Nations were obligated to enforce the resolution approved by the UNGA and independently determine the nature of their contribution to WRY. While the WRY appeal was extended to all countries, each member nation retained the autonomy to offer material and financial aid to refugees based on their own “methods and traditions.” The decision of which type of refugees each country would assist was left to the discretion of each country. While certain member states opted for the permanent retention of their WRY committees, others simply chose to prolong the duration of WRY beyond its initial expiration of June 1960. The WRY led to the formation of over 40 national committees worldwide, including in Canada. The national committees comprised individuals from many organizations and often functioned with the backing of the state. Furthermore, a handful of these national committees were responsible for overseeing advertising, fundraising, and the allocation of funds to refugees, in addition to their collaboration with national governments. The committees were widely regarded as the primary driving force behind the global success of the WRY campaign.[4]

Establishment of the Canadian Committee for World Refugee Year

The task of organizing the Canadian Committee for World Refugee Year (CCWRY) fell to Willson Woodside, a Canadian journalist known for his wartime reporting and who later became the Foreign Editor at Saturday Night magazine, and the Executive Director of the United Nations Association in Canada.[5] Reuben C. Baetz, executive director of the Canadian Red Cross, became the CCWRY’s executive chairman. The national committee’s sole salaried staff member was Muriel Jacobson, formerly an officer of the Canadian Association of Adult Education, who became its national director.

In early July 1959, the CCWRY was in the process of drafting a Programme of Action to be launched in September 1959. During the summer months, the CCWRY hoped that it could keep the idea of World Refugee Year present in the public consciousness through news media and political lobbying. Woodside corresponded frequently with Members of Parliament who spoke about the WRY before the House of Commons to thank them for their support but to also inform them of non-governmental efforts on behalf of the WRY across Canada.[6] The CCWRY’s new National Director, Muriel Jacobson, also brought her advocacy of WRY efforts before Canadian parliamentarians. In her correspondences with Ottawa, Jacobson hoped that the voluntary service agencies, who were implementing the recently-established committee’s objectives, would receive new impetus for their work due to the supportive statements from public officials.

The aforementioned objectives were…

- to focus attention on the refugee problem, and to promote among the people of Canada a sympathetic interest in the plight of refugees throughout the world;

- through its publicity, to help those participating organizations which are already engaged in refugee work to raise more money than they would normally be able to do; and

- to establish a central fund to which contributions can be made for United Nations refugee programmes.[7]

Following its establishment, the Canadian Committee for World Refugee Year would be sponsored by a diverse group of over 40 organizations representing a broad spectrum of Canadian social, economic, and religious life. With a broad array of institutional support, the CCWRY also received support from ethnocultural communities across the country and sought out potential sponsors, including: Bahai National Association, Canadian Polish Congress, Ukrainian Canadian Committee, and the Chinese Canadian Association, to name a few organizations.[8]

Getting Canadians Involved: Establishing a Network of Local Committees

The CCWRY implored the Canadian public to get involved in the WRY by assuming the “greatest possible personal responsibility” in their local communities. The committee suggested that step 1 was to organize a “working party,” either a joint group representing various elements of an individual’s community or as a committee selected by the mayor and comprised of the community’s leading citizens. Step 2 of organizing a community committee involved implementing a meeting whereby members could become acquainted with the refugee issue. The CCWRY recommended the use of a film as a focus of discussion or engaging a knowledgeable speaker who could speak about refugees. Step 3 involved informing and educating members of the local community about the refugee issues in order “to awaken them to their responsibilities.” This meant stimulating public action, by lobbying federal and provincial officials to become better aware of the plight of the world’s refugees and to push for a Canadian response. In terms of stimulating private action, this meant fundraising efforts in local refugee-focused projects whereby donations would then be sent to the CCWRY’s Central Fund.

Local committees then shifted gears from preparations to actions. In Step 4, the CCWRY asserted that a local committee’s interests were now set. Therefore, the community committee could now plan the local campaign for World Refugee Year. In order to tell the story of refugees, the CCWRY recommended for local groups to write a series of vignettes as brief fill-ins for newspapers or as texts for public-service ads, or a one-minute announcements for radio. The CCWRY also suggested creating lists of prominent local residents in municipal affairs, business, labour, or the professions “who have made good” after resettling in Canada. Other ideas included a film premiere, establishing special events with Thanksgiving being an ideal occasion.[9]

The efforts to galvanize Canadian public sentiment towards the plight of the world’s refugees depended on a network of local committees and contacts which spanned the whole country from Victoria to Halifax. These local groups were located across Canada; in its major centres, but also in its smaller cities and towns such as Port Hope (Ontario) and Shawinigan (Quebec).[10] Local committees also set imaginative targets and fundraising goals. For example, the Toronto Committee set a provisional goal of fundraising $325,000. The local committee then decided to adopt a refugee camp in Europe and raised the funds to close it permanently.[11]

Lobbying Canadian Officials to Support the World Refugee Year

Various sectors of Canadian society raised awareness of the WRY and the global refugee issue. As part of its commitment to the international community, the federal government pledged to contribute $850,000 to the UN’s refugee programs in 1960. This amount included $290,000 to the UNHCR, $500,000 to UNRWA (plus 1.5 million dollars worth of flour), and $60,000 to the Intergovernmental Committee for European Migration (ICEM), today known as the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The funds were allocated in U.S. dollars and Canada’s contribution was only exceeded by the United States ($25.17 million) and the United Kingdom ($5.68 million).[12]

As the CCWRY lobbied federal officials to support the WRY, so too did concerned citizens. Dorothy Henderson, a concerned citizen in King, Ontario, wrote to several Members of Parliament, representing the Progressive Conservative, Liberal, and Co-Operative Commonwealth Federation parties, to urge federal parliamentarians to amend immigration policy in order so that a reasonable number of “difficult cases” from Europe could be admitted to Canada. Henderson demonstrated her knowledge of existing international efforts, including Canadian contributions to the UNHCR’s Camp Clearance Program, and the ICEM. While Henderson commended federal initiatives to help refugees under the UNHCR’s and UNRWA’s mandates, she observed that “Somehow these gifts [of wheat flour and surplus milk to UNRWA and $290,000 to the UNHCR’s Camp Clearance Program] do not add up to what most thinking Canadians feel is our share to meet our responsibilities toward this great world need…”[13]

The CCWRY also requested its sponsoring organizations to write to federal parliamentarians expressing their support of Canadian and international efforts to assist refugees during WRY. On behalf of the Toronto Branch of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, a sponsoring organization of the CCWRY, a Mrs. A.N. Fraser wrote to the Secretary of State for External Affairs, Howard Green, to commend him for his address before the UNGA in New York. Green had indicated in a speech that Canada would waive normal immigration requirements and admit a substantial number of tubercular refugees and their families to Canada. Many national voluntary service organizations, including the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, were pleased to hear that the Canadian government was committed to provide maintenance payments to families who were unable to support themselves while a family member was under treatment for tuberculosis.

The Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom noted in its correspondence with the Secretary of State for External Affairs that “We are sure that with the marked decline in the incidence of tuberculosis in recent years are the shortened period of treatment, many sanatoriums [sic.] have ample accommodation available. We feel sure that within a short period of time such ‘hard core’ refugees will be supporting themselves and in due course making a vital contribution to the community.”[14] The organization hoped that the arrival of the tubercular refugee movement represented only the beginning of the re-establishment of additional disabled groups and the further modification of medical requirements for entrance into Canada. The organization concluded its remarks by stating: “Surely, our country with its vast wealth can assist to a much greater extent than the ‘one hundred families’ mentioned in the press report. We are anxious that Canada should play its full part in alleviating the disproportionate number of refugees already carried by smaller European countries.”[15]

Admission of Sponsored Refugees

As part of its contribution to the WRY effort, the Canadian government authorized the admission of sponsored refugees. This included prospective applicants who typically did not meet the admission criteria but who would be looked after by family relatives or interested persons. Canadian immigration standards mandated that sponsored refugees had to possess good health and a high likelihood of being self-sufficient in Canada. An exemption could be granted for those sponsored by family who were willing to provide care for them upon their arrival in the country. During WRY, non-governmental sponsors of refugees from Europe were required to fulfill the following criteria:

- be reliable and financially able to carry out responsibilities;

- be prepared to provide transportation to Canada;

- be prepared to accommodate, maintain, and obtain employment for the refugee following their arrival, and provide any assistance to the refugee as needed;

- be willing to help the refugee make the necessary social adjustment;

- provide assurance, where the refugee suffers from illness which will require treatment in Canada, that they will receive the medical care they need. When the illness is such that institutional care is necessary, the approval of the provincial health authorities must be obtained before the refugee can be permitted to come to Canada.[16]

Immigration officials anticipated that the immigrant would possess a commendable moral character, be devoid of serious mental health challenges, be willing to undergo medical treatment or supervision as mandated in Canada, and be willing to relocate to Canada for permanent residency. The Canadian government did not impose any restrictions on the duration or scope of the sponsor’s acknowledged responsibilities.

Provinces and municipalities were typically responsible for taking care of impoverished residents in Canada. If a sponsored immigrant required help, it became a financial burden on the municipality or the province if the sponsor failed to fulfill the obligations they agreed to when seeking entry into the country. As a result, federal immigration authorities mandated that potential refugee sponsors assume complete liability for the individuals admitted to Canada under their sponsorship until they qualified for regular provincial and local social and welfare services.[17]

Admission of Unsponsored Refugees

During World Refugee Year, the Department of Citizenship and Immigration outlined the criteria for unsponsored refugees in Europe to be considered for immigration to Canada. These criteria included being in good health, having good character, and demonstrating the potential to succeed in Canada. It was anticipated by federal officials that each head of household would have the ability to financially support their dependents, and that any minor physical problems they or their family members had would not prevent them from being admitted to Canada. Furthermore, alongside the current program, the Canadian government introduced a distinct humanitarian initiative aimed at relocating refugees afflicted with tuberculosis and their relatives to Canada. The federal government covered the expenses associated with bringing tubercular immigrants to Canada, as a significant number of refugees lacked the financial means to pay for their journey to Canada. Certain refugees were granted interest-free loans from the Canadian Assisted Passage Loan Fund by federal officials. Refugees were required to reimburse their debt with periodic payments when they settled in Canada.[18]

Regarding the facilitation of admission for these refugees, Canadian officials stated that individuals, organizations, agencies, and provincial and municipal authorities could visit their nearest Immigration Office to identify the refugee(s) they wanted to assist and specify how they could provide assistance. The pamphlet provided a list of six Canadian migration agencies that had international connections and could aid in the direct sponsorship of refugees in Europe. These agencies included the Canadian Christian Council for the Resettlement of Refugees, Catholic Immigrant Services, the Canadian Council of Churches, Canadian Jewish Congress, Jewish Immigrant Aid Services, and the Canadian Committee for World Refugee Year. Subsequently, each Immigration Office would transmit the name(s) of the refugee(s) to a Canadian Visa Officer stationed in Europe, together with information regarding the type and extent of support pledged by the closest entity in Canada. Subsequently, refugees were required to reach out to the closest Canadian Visa Office in order to have their immigration application assessed. In Canada, the interested guarantor was expected to accept the refugee, arrange housing, facilitate work if needed, and aid in their social integration in Canada.[19]

If a refugee was found to not comply with normal immigration requirements, prospective sponsors were given the opportunity to assume more extensive sponsorship responsibilities or facilitate the admission of other refugees. If a prospective sponsor was not able to fully assist a preselected refugee, they could then contribute towards their transportation to Canada. Immigration officials noted that such expenses averaged approximately $200 per refugee and interested parties could make a financial contribution at any Immigration Office where a receipt would be provided for income tax purposes.[20]

Tubercular Refugee Movement

As part of the its commitment to finding a solution to plight of Europe’s remaining unsponsored refugees, many of whom were deemed “hard core” due to illness, infirmity, or disability and had not been permanently resettled, the Canadian government admitted 100 tubercular refugees and their families to Canada. With the collaboration of provincial health authorities, the tubercular refugees would be placed in provincial sanatoria until they were given a clean bill of health, while their family members would be financially supported by the federal government. The tubercular refugees and their families were resettled in every Canadian province, except Newfoundland & Labrador, where provincial officials had stipulated that only tubercular refugees with existing family members already resident in the province would be accepted.[21]

Given the success in the rehabilitation of the first group of 100 tubercular refugees and their 245 family members, between December 1959 and February 1960, federal officials drew on the positive public response to the refugees’ resettlement by subsequently accepting a second group (111 tubercular refugees and 98 dependents), and a third group (114 tubercular refugees and 158 dependents) between July 1960 and March 1961. In all, 325 tubercular cases and 501 family members were brought to Canada as part of the tubercular refugee movement.[22]

In commending the federal government for permitting the entry of 100 tubercular refugees and their families, the Co-Operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), a forerunner of the New Democratic Party (NDP), also criticized federal officials for not doing enough to help refugees in Europe. In a December 1959 press release, the CCF leader, Major James W. Coldwell, expressed his dissatisfaction with the federal response by stating “I am concerned to note, however, that the government appears to consider that Canada should do little more than this to mark World Refugee Year. I am sure that the government completely misjudges the good will of the Canadian people.” Coldwell went on to suggest that the mere admission of some 100 tubercular refugees was “…no more than a token, a gesture…” yet recognizing that their resettlement would be life-changing. The opposition party then called on the Canadian government to admit some 2,500 tubercular refugees and their families from Europe as some 2,700 beds were available in provincial sanatoria due to the successful treatment of tuberculosis in Canada in recent years.[23]

A tubercular refugee family poses for a photo with Canadian immigration officials after disembarking from their plane. They formed part of the second group within the tubercular refugee movement admitted to Canada during World Refugee Year (1959-1960), Ancienne Lorette Airport, Québec, 20 July 1960.

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (D2014.360.49)

Fundraising Initiatives during World Refugee Year

Alongside resettlement of refugees, the CCWRY was involved in a number of diverse fundraising initiatives that served to raise public awareness of WRY and refugee issues around the world. Aside from the publication of promotional materials, lobbying public officials for support of the WRY and the resettlement of refugees, fundraising was also an important component in the international effort to assist refugees. Across Canada, a number of diverse schemes were implemented to raise funds during WRY.

Saskatchewan Government Telephones

The Saskatchewan Committee for World Refugee Year engaged with the provincial utility, Saskatchewan Government Telephones, in a plan that was the first of its kind in North America. First used in Switzerland with success, Saskatchewan Government Telephones arranged for its province-wide system to be used during the month of March 1960, whereby its subscribers simply dialed their long-distance operator, gave their name and telephone number, and indicated the amount that they wished to donate to World Refugee Year efforts.[24]

Cross-Border Fundraising Plan

When it came to a national appeal, the CCWRY proposed a border crossing fundraising campaign to federal officials in Ottawa. With the approval of the federal government, the plan was put into operation for the 1960 tourist season (beginning after Victoria Day and continuing through Labour Day), and provided an opportunity for Canadians crossing the border into the United States (and Americans returning from Canada to the United States) to make contributions to the CCWRY’s Central Fund. The fund allocated its contributions to the priorities outlined by the offices of the UNHCR, UNRWA, and the Canadian government: resettlement of the remaining postwar refugees in Europe, vocational training for young Arab refugees in the Middle East, transportation assistance to European refugees in China, and assistance to Algerian refugees in Morocco and Tunisia, and Chinese refugees in Hong Kong.

The CCWRY proposed that containers be installed near Customs and Excise counters and other suitable locations at various land border ports of entry across the country. To prevent traffic congestion at these locations, Canadian customs officials were not required to solicit donations on behalf of the WRY. The Customs of Excise Officers’ Association was invited to participate in the project by periodically emptying the containers, depositing the donated funds, and sending equivalent cheques to the CCWRY. To advertise the fundraising plan, billboards were installed in areas leading up to the border ports of entry, and television, radio and press media were engaged.

Underpinning the border-crossing plan was its educational relevance to the cause of refugee assistance. The plan raised awareness on the part of Canadian and American travelers of free borders, a lack of passport restrictions, funds for travel, among others – all privileges denied to refugees. The CCWRY also indicated to federal officials of the likelihood that Canadian tourists would likely be in a “holiday-generosity mood rather than in their normal situations of community responsibility.” The plan was presented so as not to impede border traffic, did not require public solicitation on the part of federal officers, nor was it to be resented by outgoing and returning travellers. Important to federal officials was the fact that the cross-border plan not be used as a precedent for other organizations to request similar privileges.[25]

Canadian Universities Campaign

A number of university organizations including the Canadian Federation of Newman Clubs, Canadian Federation of Catholic College Students, National Federation of Canadian University Students, Student Christian Movement of Canada, and World University Service of Canada sponsored a “Canadian Universities Campaign” on behalf of WRY. Subsequently, campaign committees were formed in most Canadian universities to raise funds under the slogan, “Each One Raise One” and “Une Personne, Un Dollar.” A February 1960 press release by the coordinated campaign claimed that there were about 100,000 students and faculty members in Canada thereby necessitating a fundraising target of $100,000. The funds raised were to be sent to the CCWRY’s Central Fund, with 25 percent of the monies received going to the UNHCR’s Camp Clearance program in Europe, while the other 75 percent of funds would be divided among projects designed to assist refugee students and professors in Algeria, Hong Kong, and Korea.[26]

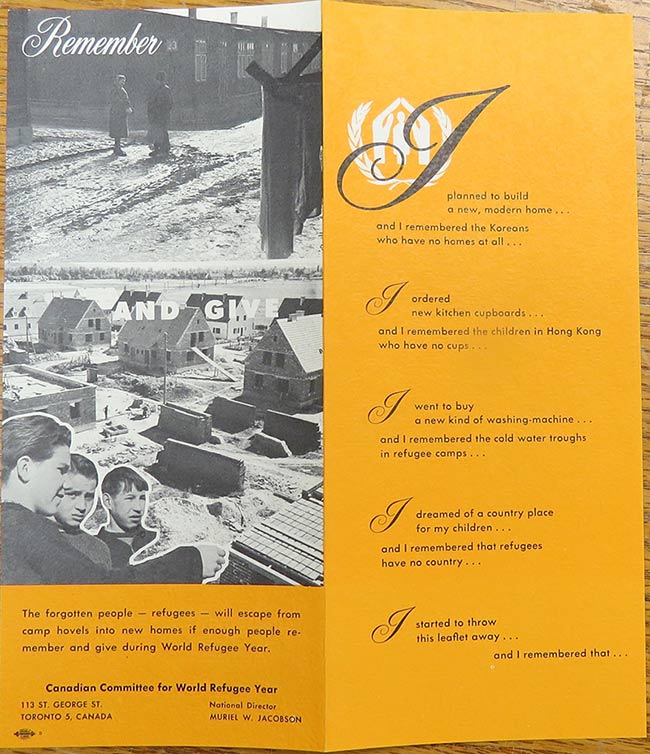

Canadian Committee for World Refugee Year (CCWRY) pamphlet entitled, “Remember and Give,” on behalf of World Refugee Year, 1959-1960.

Credit: McMaster University, William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, CCWRY fonds, RC0072, box 1, file 13 (Canadian University campaign, 1960-1961)

Austerity Week

In May 1960, the Canadian WRY campaign conducted an ‘Austerity Week’ during which contributions were sent to local authorities after sympathetic Canadians made contributions resulting from their self-denial in purchasing goods as a response to the motto, “Don’t spend it – send it.” In an effort to highlight a “family dimension,” to the initiative, the national committee asked for fundraising suggestions that involved “sacrificing the Thanksgiving meal.”[27]

During Austerity Week, concerned citizens in Kincardine, Ontario, raised $2191.23 from various local clubs and organizations. Local residents expensed $400.40 in attempting to resettle three refugee families in the community. It was their wish that the remaining donated funds be sent overseas to assist refugee children in either Hong Kong, Tunisia, or Morocco.[28] Other Canadians chose to have their donations sent to the Arab refugees in the Middle East, including the Edythe Stewart Auxiliary of the local Wesley United Church, in Fort William, Ontario, which sent $400 to the CCWRY. It was the group’s hope that the monies collected could be used for one refugee family in order to establish a personal relationship between the association and the family.

The CCWRY responded by recognizing the problem with attempts by local groups to “…raise funds for a vague generalization…” rather than for an established personal relationship between the donor and the refugee. Despite this realization, the CCWRY indicated that there were considerable difficulties in providing special assistance to individual cases, when UNRWA staff were overburdened by their current activities on behalf of refugees.[29]

Conclusion: World Refugee Year Comes to an End

The WRY concluded on 30 June 1960, but many of its promotional, fundraising, and refugee resettlement initiatives continued long afterwards, including the CCWRY which remained in existence until 30 September 1960. Under the auspices of the CCWRY and its supporting organizations, the Canadian public helped to raised over $1.8 million. The Canadian government contributed a further $600,000 in cash and $1 million in in-kind contributions, i.e. wheat flour and milk, to bring the overall contribution to $3.4 million.[30] When it came to refugee resettlement during WRY, approximately 32,000 European refugees were transported by ICEM for permanent resettlement overseas.[31] Of the 4,985 refugees admitted to Canada during the period of WRY and until the end of December 1960, 3,508 entered specifically as a result of WRY endeavours.[32]

One such example was the Wosik household, a Polish refugee family, who were brought to Canada during WRY. Josef, who had tuberculosis, and his wife, Agnieska, had survived German concentration camps and slave-labour programs only to later find themselves as unwilling residents of a DP camp in Germany. In the 15 years after the Second World War, Josef’s tuberculosis was initially seen by the family as an affliction that prevented them from finding permanent resettlement. Yet, Canada’s tubercular refugee scheme had turn Josef’s condition into a blessing. In January 1960, the Wosik family, including their two children, Barbara (aged nine) and Josef (aged five), left the Braunschweig DP camp and boarded a train for Hamburg where International Refugee Organization (IRO) officials examined the family’s paperwork, including the elder Josef’s X-ray plates of his lungs. The Wosik family arrived at Toronto’s Malton Airport and soon after Josef was admitted into a sanatoria at Weston (Ontario) until he was cured.[33]

To mark the official termination of the World Refugee Year, a luncheon meeting was held on 29 June 1960, at the Park Plaza Hotel in Toronto. As Patron of the CCWRY, Governor-General Georges P. Vanier, provided the closing message to those in attendance. In his remarks, Vanier observed that while it might have been too early to conclude whether World Refugee Year in Canada was an unqualified success, he believed that “…many Canadians can feel justifiably proud of the generous contributions which they, and their communities, have made.” The 45 local World Refugee Year Committees along with over 40 voluntary agencies that sponsored the CCWRY went to great lengths to meet their fundraising targets and other obligations. These collected funds would be used to close down the remaining refugee camps in Europe, provide technical training to young Arab refugees, resettle White Russian refugees stranded in China, and provide relief to Chinese refugees in Hong Kong.

According to the Governor-General, the single greatest contribution of all the World Refugee Year committees in Canada was the fact that “…many thousands of us have been made deeply aware, for the very first time, of the desperate plight of so many refugees … Much still needs to be done.” In his address, Vanier pointed to the Canada’s history and geographical “good fortune” for being spared the “disaster we are now helping to alleviate.”[34]

- Louise W. Holborn, Refugees: A Problem of Our Time: The Work of The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 1951-1972 (Metuchen, NJ: The Scarecrow Press, 1975), 450.↩

- Holborn, Refugees, 450.↩

- Holborn, Refugees, 451-452.↩

- Holborn, Refugees, 453.↩

- McMaster University, William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, Canadian Committee for World Refugee Year [hereafter CCWRY] fonds, RC0072, box 1, file 8 “Correspondence, Ottawa and sponsoring organizations, 1959-1960,” letter from Willson Woodside, National Director, UN Association in Canada, to Hon. Paul Martin, M.P., House of Commons, Ottawa, 24 June 1959.↩

- McMaster University, William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, CCWRY fonds, RC0072, box 1, file 8 “Correspondence, Ottawa and sponsoring organizations, 1959-1960,” letter from Willson Woodside, National Director, UN Association in Canada, to Herbert W. Herridge, M.P., House of Commons, Ottawa, 24 June 1959.↩

- McMaster University, William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, CCWRY fonds, RC0072, box 1, file 8 “Correspondence, Ottawa and sponsoring organizations, 1959-1960,” letter from Muriel W. Jacobson, National Director, CCWRY, Toronto, to Hon. Paul Martin, M.P., House of Commons, Ottawa, 6 July 1959.↩

- McMaster University, William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, CCWRY fonds, RC0072, box 1, file 1 “Contact List, 1959-1960,” Canadian Committee for World Refugee Year, “Mailing List as of June 30, 1959,” 1-10.↩

- McMaster University, William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, CCWRY fonds, RC0072, box 2, file 1 “Correspondence, United Nations Information Service #1, 1959-1960,” pamphlet, UN, World Refugee Year, Supplement to Newsletter No. 13, 5 October 1959, 1-12.↩

- McMaster University, William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, CCWRY fonds, RC0072, box 1, file 1 “Contact List, 1959-1960,” Canadian Committee for World Refugee Year, “World Refugee Year – Community Committees/Contacts,” 1-4.↩

- McMaster University, William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, CCWRY fonds, RC0072, box 1, file 9 “Correspondence, with Ottawa, 1959-1961,” press release no. 15, Canadian Delegation to the United Nations General Assembly (Fourteenth Session), “Statement by Mrs. Alene Holt, Canadian Representative on the Third Committee of the United States General Assembly,” 3 November 1959, 5. See handwritten notes.↩

- McMaster University, William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, CCWRY fonds, RC0072, box 1, file 2 “Correspondence, United Nations with Muriel Jacobson and Peter Casson, 1959-1961,” “Government Contributions Pledged for UN Refugee Programmes for 1960 (in U.S. Dollars),” n.d.↩

- McMaster University, William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, CCWRY fonds, RC0072, box 1, file 8 “Correspondence, Ottawa and sponsoring organizations, 1959-1960,” letter from Dorothy C. Henderson, King (Ontario), to Hon. Howard C. Green, Secretary of State for External Affairs, Ottawa, 14 August 1959.↩

- McMaster University, William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, CCWRY fonds, RC0072, box 1, file 8 “Correspondence, Ottawa and sponsoring organizations, 1959-1960,” letter from A.N. Fraser, Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, Toronto Branch, to Howard Green, Secretary of State for External Affairs, Ottawa, 2 November 1959.↩

- McMaster University, William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, CCWRY fonds, RC0072, box 1, file 8 “Correspondence, Ottawa and sponsoring organizations, 1959-1960,” letter from A.N. Fraser, Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, Toronto Branch, to Howard Green, Secretary of State for External Affairs, Ottawa, 2 November 1959.↩

- Department of Citizenship and Immigration [hereafter DCI], “Admission of Refugees to Canada during the World Refugee Year,” 1960. Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 [hereafter CMI] Collection (D2013.1222.1), 5.↩

- DCI, “Admission of Refugees to Canada during the World Refugee Year,” 1960. CMI Collection (D2013.1222.1), 5-6.↩

- DCI, “Admission of Refugees to Canada during the World Refugee Year,” 1960. CMI Collection (D2013.1222.1), 3.↩

- DCI, “Admission of Refugees to Canada during the World Refugee Year,” 1960. CMI Collection (D2013.1222.1), 3-4.↩

- DCI, “Admission of Refugees to Canada during the World Refugee Year,” 1960. CMI Collection (D2013.1222.1), 4-5.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, Immigration Branch fonds, RG 76, volume 860, file 555-53-1, part 4, “T.B. Refugee Family Movement World Refugee Year - General File,” memorandum, “Establishment of Tubercular Refugees,” from Chief of Operations, Immigration Branch, Department of Citizenship and Immigration, Ottawa, 22 September 1961, 1-4.↩

- Canada, Parliament, House of Commons, House of Commons Debates: Official Report, Fourth Session – Twenty-Fourth Parliament, Volume 1 (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer and Controller of Stationery, 1961),1026; Canada, Parliament, House of Commons, House of Commons Debates: Official Report, Fourth Session – Twenty-Fourth Parliament, Volume 4 (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer and Controller of Stationery, 1961), 4069. For further context, see Jan Raska, “Welcoming the Sick and Afflicted: Canada’s Tubercular Admissions Program, 1959-1960,” Histoire sociale/Social History 52:105 (May 2019): 171-192.↩

- McMaster University, William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, CCWRY fonds, RC0072, box 1, file 9 “Correspondence, with Ottawa, 1959-1961,” press release, Co-Operative Commonwealth Federation, “Statement on World Refugee Year by M.J. Coldwell, National Leader of the CCF,” 31 December 1959.↩

- McMaster University, William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, CCWRY fonds, RC0072, box 1, file 10 “Correspondence, with Ottawa, 1959-1960,” letter from Muriel Jacobson, National Director, CCWRY, Toronto, to Hon. G.C. Nowlan, Minister of National Revenue, Ottawa, 8 March 1960, 1-2.↩

- McMaster University, William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, CCWRY fonds, RC0072, box 1, file 10 “Correspondence, with Ottawa, 1959-1960,” letter from Muriel Jacobson, National Director, CCWRY, Toronto, to Hon. G.C. Nowlan, Minister of National Revenue, Ottawa, 8 March 1960, 1-2. See attached memorandum, “Proposed Canada-USA Border Crossing Fund Raising Plan for World Refugee Year,” 1-4.↩

- McMaster University, William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, CCWRY fonds, RC0072, box 1, file 13 “Canadian University campaign, 1960-1961,” press release, World Refugee Year: Canadian Universities Campaign, 11 February 1960.↩

- Peter Gatrell, Free World? The Campaign to Save the World’s Refugees, 1956-1963 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 159.↩

- McMaster University, William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, CCWRY fonds, RC0072, box 1, file 4 “Correspondence, 1961,” letter from Doris E. Milne, Kincardine (Ontario), to Muriel Jacobson, National Director, CCWRY, Toronto,” 3 January 1961.↩

- McMaster University, William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, CCWRY fonds, RC0072, box 1, file 4 “Correspondence, 1961,” letter from S.M. Moss (on behalf of Muriel Jacobson, UNHCR Correspondent in Canada), to Mrs. Watson Slomke, Fort William (Ontario),” 21 November 1961; McMaster University, William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, CCWRY fonds, RC0072, box 1, file 4 “Correspondence, 1961,” letter from S.M. Moss (on behalf of Muriel Jacobson, UNHCR Correspondent in Canada), to Mrs. E.W. Slomke, Fort William (Ontario),” 9 August 1961.↩

- Holborn, Refugees, 461-463.↩

- United Nations [hereafter UN], Yearbook of the UN, 1961 (New York: Office of Public Information, UN, 1963), 332. This group included 1,501 individuals designated as “handicapped” refugees.↩

- United Nations Archives and Records Management Section [hereafter UNARMS], Series S-0846 (Subject files of Secretary-General: Dag Hammarskjold), box 1, file 8, acc. DAG 1/5.1.3, item S-0846-0001-08-00001 “Agencies and Organs – World Refugee Year, 1959-1961 – Correspondence and Reports, 22/10/1960 – 28/02/1961,” Supplementary Report to the Secretary-General by His Special Representative for World Refugee Year, 30 September 1960 – 28 February 1961, 7.↩

- Frank Lowe and Louis Jaques, “Josef Wosik Gets a Chance to Live,” Weekend 10.13 (1960): 2-3. The article misspells Agnieska as “Agneerzka.”↩

- McMaster University, William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, CCWRY fonds, RC0072, box 1, file 9 “Correspondence, with Ottawa, 1959-1961,” “His Excellency, Major General Georges P. Vanier, D.S.O., M.C., C.D., Governor-General of Canada, addresses the Canadian people as Patron of the Canadian Committee for World Refugee Year on the occasion of the official termination of the Year in Canada,” n.d., 1-2.↩