By Steven Schwinghamer, Historian

As we approach the centenary of the Chinese Immigration Act, 1923, answering three key historical questions will help us understand and make meaning of the legislation: What was the 1923 Act that closed the door on Chinese immigration? How did the politics of exclusion develop in Canada? What were the consequences?

What was the Chinese Immigration Act, 1923?

The Chinese Immigration Act, 1923 was intended to prevent Chinese immigrants from entering Canada. The crux of its language came in its fifth paragraph, on entry and landing, where it laid out the acceptable classes for entry. Under the Act, the only classes of persons of Chinese origin or descent allowed to enter Canada were governmental representatives, merchants, and students, along with children of Chinese descent born in Canada who had gone out of the country “for educational or other purposes.” All Chinese immigrants were required to enter only at a port of entry, and any immigrant of Chinese descent outside the admissible classes could only be inspected at Victoria or Vancouver, British Columbia.[1]

These harsh terms led to the Act being called the “Chinese Exclusion Act.” The day it came into force, 1 July 1923, was known as “Humiliation Day,” and Dominion Day (later, Canada Day) was tainted by the association with the discriminatory law.

Before 1923

The Chinese Immigration Act, 1923 proceeded from an extensive history of discrimination against Asian immigrants broadly, and against Chinese immigrants specifically, in British Columbia and in Canada. An initial collaborative co-existence around certain industries—mining, lumber, or construction—dissolved in concert with the shift from resource extraction to settlement. For instance, “Chinatowns” were earlier a source of interest, curiosity, and largely amenable contact between communities; but with a new emphasis on residence and settlement, the separation (created and enforced by white society) was blamed on Chinese immigrants’ supposed inability to assimilate.[2]

In the late 1800s, the shift in perception of Asian immigrant workers from needed labour to potential competitors had a profound effect on domestic politics. By way of response, Canada and the neighbouring United States of America “in efforts to regulate and discipline Asian mobility, drew and enforced a new racialized geography of exclusion.”[3] A significant factor in this shift in Canada was the conclusion of the transcontinental railway project, which led to a shift in views of both the connected fabric of the Canadian polity and the desirability of the associated Chinese labour force. The same year that the last spike was driven in the Canadian Pacific Railway (1885), a commission of inquiry was struck to inquire “concerning all the facts and matters connected with the whole subject of Chinese Immigration, its trade relations, as well as the social and moral objections taken to the influx of the Chinese people into Canada.”[4]

The result of the report was a recommendation of restrictions against Chinese immigration into Canada, with a duty, the Head Tax, of ten dollars be charged against each immigrant (with some narrow exceptions). The federal government immediately implemented a much higher amount, fifty dollars, but this action did not appease anti-Asian agitators. As Chinese workers were laid off from railway work, labour competition sharpened and the racism against Chinese workers—brought to Canada shortly before as essential labour—built to a violent peak in early 1887. Chinese Canadians were intimidated, targeted for violence against their persons and their property, and expelled from the city during a long lead-up to an anti-Chinese riot on 24 February 1887.[5] The racism did not abate, and popular public and political pressure continued to push for ever-harsher restrictions on Chinese immigration. The Head Tax escalated sharply in and after 1900, reaching five hundred dollars in 1903.[6]

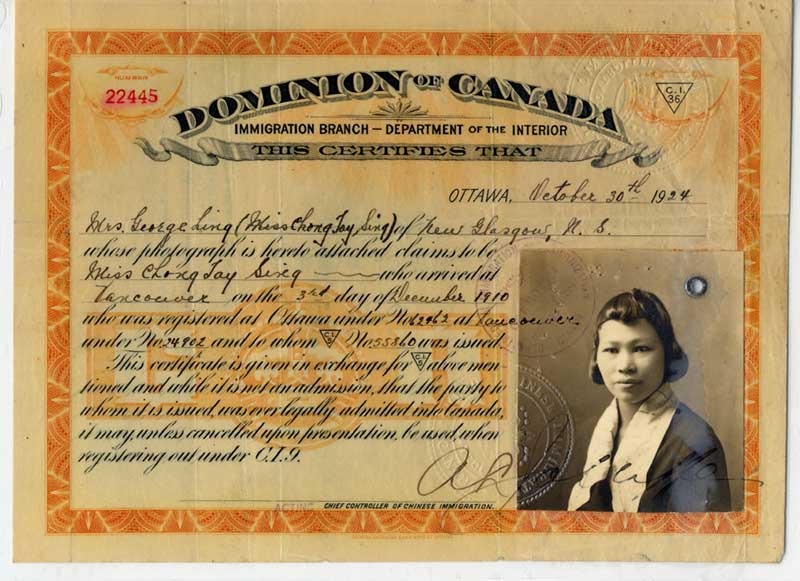

Credit: Donated by Mary Mohammed. (DI2020.8.15)

Broader Anti-Asian Discrimination

Anti-Asian racist activists were not satisfied with these restrictions. Amid increasing immigration from other Asian countries of origin—notably Japan and India—their xenophobia erupted violently again in the Vancouver anti-Asian riot of 1907, with substantial damage to Asian immigrants’ property. Although it may be argued that the principal catalysts for the riot were related to increases in Japanese immigration and a contemporary expulsion of Sikh immigrants from an American town not far from the border, the mob incited by the Asiatic Exclusion League’s rally and parade on 7 September 1907 also targeted Chinese businesses.[7]

Remarks before and after the riot reveal one critical aspect of Canada’s anti-Asian policy environment: how citizens of other countries were received in Canada was and remained an enduring component of international relations. For instance, the perception and fact of Japan’s increasing power as a state was reflected in remarks by Prime Minister Laurier specifically on racist behaviour: “up to [ten years ago], the Asiatic, when he came to white countries, could be treated with contempt and kicked,” but that with their new economic and military strength, Japanese citizens “will not submit to be kicked and treated with contempt, as his brother from China still meekly submits to.”[8] And indeed, this judgement of difference informed the response to the riot, wherein compensation for Japanese residents was immediately considered while the Sir Wilfrid Laurier and his cabinet had to be cajoled into compensating affected Chinese residents.[9]

Further, the riot was followed by a 1908 diplomatic agreement to limit immigration from Japan based on a quota; an effort to reach a similar arrangement with China failed the following year.[10] Much later, after exclusionary policies were largely removed, a small family reunification program between (communist) China and Canada unfolded as an important gesture in the contentious atmosphere of Cold War international relations.[11]

Earlier Calls for Exclusion

The policy background might be clarified through the actions of one of British Columbia’s elected officials in the early twentieth century, Henry Herbert Stevens. Stevens was a newspaper editor, city councillor, Member of Parliament and federal cabinet minister, as well as an inveterate racist. Further, he was no marginal politician: his elected federal career spanned about thirty years.[12] Stevens gathered his commentaries on Japanese, Hindu (sic), and Chinese immigration into a single pamphlet titled The Oriental Problem. Regarding Chinese Canadians, Stevens asserts that “in many respects the Chinese are the least objectionable of all classes of Orientals” but argues that the community is unassimilable, uninterested in what he terms “pioneering,” that they operate slaving and prostitution rings within their community, and that the community is engaged in widespread fraud and illegality in relation to the immigration regulations. Stevens, more than a decade before the Chinese Immigration Act, 1923, asks the rhetorical question, “do we favour Oriental immigration?” The implied answer carries from his arguments noted above, and he closes with an exhortation: “If not, then make such regulation as will exclude them effectually.”[13]

Stevens also claimed there were public and moral dangers linked to drug use in the Chinese Canadian community.[14] It is unsurprising that this moralizing flowed smoothly into the popular pseudoscience of the era, including on eugenics and population health. The use and abuse of medical reasons for refusing Asian immigrants is perhaps most elegantly crystallized in the debacle surrounding the screening of Asian immigrants for hookworm. Prevalent among Asian immigrants, hookworm was a parasite that was not a significant public health risk in Canada, as it was easily treated with existing medicines. Further, it relied on people walking barefoot in warm areas contaminated with human waste to spread – an unlikely situation in Canadian population centres. However, authorities in the United States seized upon the parasite risk to bar Asian immigrants, and anti-Asian activists in Canada followed suit.[15] The medical aspects of the pretext were disposed of neatly by Dr. Peter H. Bryce, Chief Medical Officer, who summarized the situation as “finding some new reason for excluding Hindus [rather] than from any actual evidence we have that the Hindus coming to Canada have or are suffering from this disease to a large degree.” Bryce also observed in his letter in relation to a claim in an American newspaper that Chinese immigrants suffered from hookworm, “one can only say that if laziness is the best diagnostic evidence of Hookworm then all we know of the Chinaman is that he of all people is most free of the disease as he certainly is not lazy even if he has other things to account for.”[16]

These threads of anti-Asian, and specifically anti-Chinese, discrimination hardened after the First World War. Under- or unemployment, xenophobic nationalism, and a broader immigration policy of deliberate selection were all factors in the push for exclusionary legislation against Chinese immigrants. The Chinese Immigration Act, 1923 was tabled in March 1923 and moved quickly through the legislative process, coming into force on 1 July 1923.[17]

What Came after 1923

The consequences of the exclusionary legislation were extraordinary and dire for the Chinese Canadian community. Family reunification in Canada was all but impossible for those already here, and there were few legal routes for Chinese immigrants to enter the community in Canada. Historians Jin Tan and Patricia Roy have found that only eight Chinese immigrants entered Canada from 1924 to 1946. The halt of new entries and a significant rate of return (or possibly onward emigration into the United States), meant that the community was reliant on a small Canadian-born population for growth—although that population had a much more even gender balance that the “bachelor society” of the first-generation immigrants.[18]

The circumstances of the Second World War helped to shift popular attitudes towards Chinese immigrants. The common military enemy (Japan) and the shifting anti-Asian rhetoric (from assimilation and labour issues to military threats and commercial competition) changed the public perception of China. China, beset by Japan and internal conflict, no longer fit as a “threat” when viewed through the lens of military or commercial questions, and in fact came into public sympathy.[19] This led to a marked softening in attitudes, even within the immigration branch.

Previously, immigration officials took every opportunity to deny and deport Chinese immigrants, but faced with Chinese Canadians trapped abroad by the circumstances of war, the immigration branch instead recommended a reasonable leniency and accommodation. Chinese residents in Canada were required to register when traveling abroad under the Chinese Immigration Act, 1923—another unique and targeted discrimination—and were permitted a maximum absence of two years before losing the right of re-entry.[20] In December 1940, a year before Canada had gone to war with Japan, the regulation was amended on a temporary basis to double the time the residents might be out of the country. This extension was held to be “for the peace, order, and welfare of Canada.”[21]

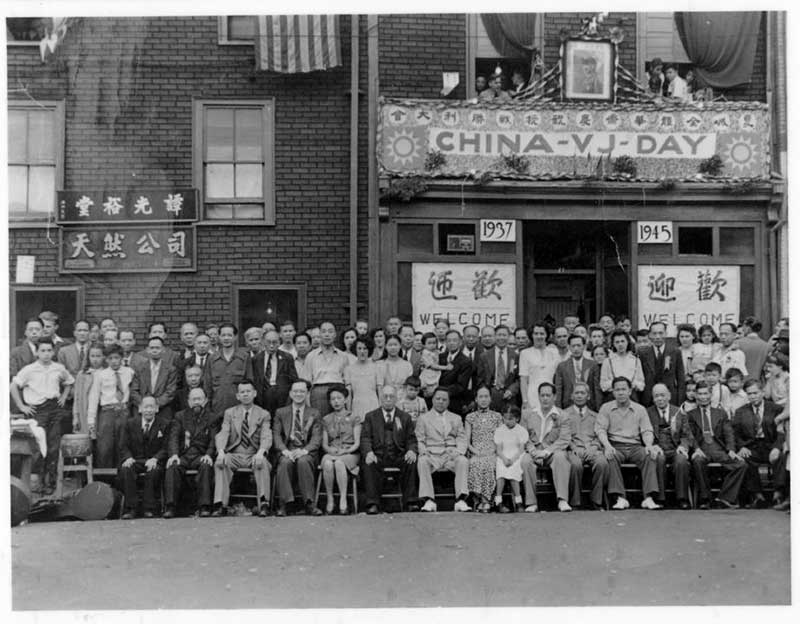

Credit: Donated by Mary Mohammed. (DI2020.8.1)

Repeal

The impact of the relaxation of immigration rules—even the repeal of the Exclusion Act itself in 1947—should not be overstated. Immigration policy remained sharply discriminatory against Chinese applicants. Stripping away the exclusionary Chinese Immigration Act, 1923 allowed Chinese Canadians to sponsor immediate relatives into the country, and that was all.[22] However, the department did increase staffing to support the many applications to bring family out of Communist China, and the result was a modest movement of Chinese into Canada, such that through the early 1950s the annual arrivals from China hovered at around two to three thousand.[23] To a community locked in exclusion for decades, however, with a total contemporary population of about 30,000, this was a significant change. That change, the repeal, was achieved by the efforts of an effective combination of civic, labour, religious, and other community powers.[24] Further activism, notably by Chinese veterans of service and their allies, secured the long-denied right to vote for the community, and the repeal of other discriminatory laws and regulations at all levels of government in Canada.[25]

The restriction on arrival to immediate family led to “paper relatives” coming to Canada: people who claimed immediate relation in order to obtain entry. Whether by purchase of authentic or forged documents, this movement created significant illegal immigration operations and substantial profits for organizers, while forcing immigrants into a fearful and vulnerable life, living in the shadows in Canada.[26] This mirrored a similar movement to the United States, arising from comparable restrictions against Chinese entry even as labour demand in North America and conflict and revolution in China pushed thousands to flee.[27] Sympathetic public pressure, effective advocacy, and mounting evidence of illegalities pushing the Canadian government to mount the Chinese Adjustment Statement Program, an amnesty for those who had entered by irregular or illegal means but who were of good character and ready to disclose and remedy their status in Canada. This program benefitted about 12,000 Chinese Canadians, mostly “paper sons,” between 1960 and 1972.[28]

Attitudes Within the Immigration Branch

Even with the repeal of the Chinese Immigration Act, 1923 and the program to regularize status, contemporary attitudes within the immigration branch deserve scrutiny. It is apparent that the 1960s brought a steady liberalization of policy. In 1962 and 1967, regulatory changes removed explicit references to “race” and introduced the first iteration of the “points system.” Generally, this bears out well, but under the surface, the early 1960s was clearly a period of deep conflict within the department over the adaptation of policy amid shifting social norms.

In 1960-61, the immigration branch was undertaking a planned overhaul of the immigration act. Even though a new act had been introduced less than a decade before, cabinet was advised that a new immigration act was needed as the existing one was “inadequate for the purpose of dealing effectively and efficiently with matters relating to immigration.”[29] In 1961 advice from the Director of Immigration to the Deputy Minister, the question of admissible categories was raised, and responses from the public servants within the department reflect deeply entrenched racism.[30] In summarizing the principles to guide admission policy for this prospective new immigration act, the summary states that “it is believed reasonable to say that Canadians generally prefer to see those of their own ethnic origins come in as immigrants; failing this they wish to see those of a similar or at least compatible origin come in.”[31] For emphasis, the summary immediately presented the ethnic composition of Canada in 1959, with British origins leading the way at 45 percent and “Negro” at the end of the list at 0.15 percent.

The mix of open and veiled racism carries throughout the papers. In discussing admissibility, the paper stated as a leading sentence, “Colour is a disability.”[32] Following this attitude, the aim was that the new regulations should “result in approximately the same volume of coloured and Asiatic immigration as in recent years.”[33] The proposed language removed any direct reference to race or nationality, but there remained room for prejudiced selection to operate. Immigrants were to be judged against unspecified standards for appropriate “social development,” be literate in suitable languages, and possess “compatible traits”. The other draft language sent forward for consideration by the deputy minister is even more stark, and is described in its advantages by the Director of Immigration as establishing “a clear-cut preference for those of European origin and makes it clear that those of coloured or Asian race must have superior qualities in order to qualify.”[34] Given the conflict between the department’s effort to maintain white European preference and changing public attitudes, it is not surprising that this effort to produce a revised act failed.

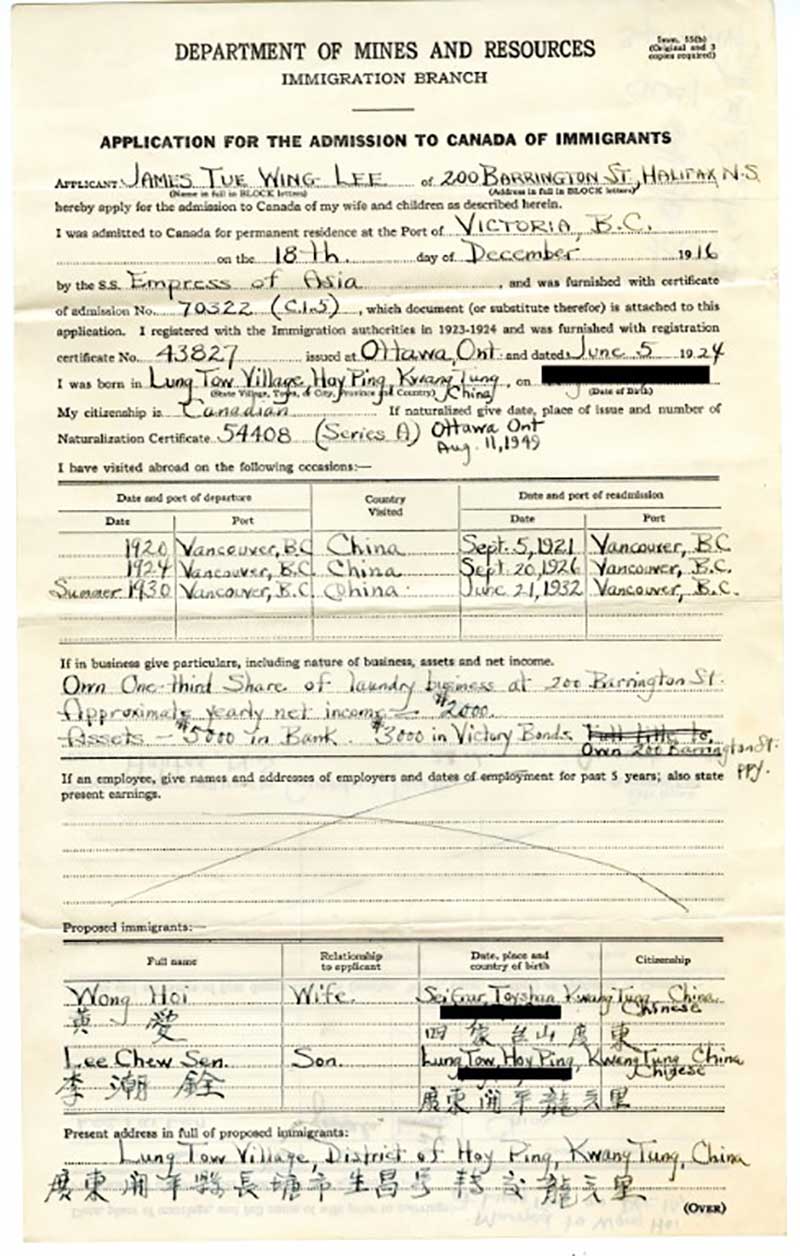

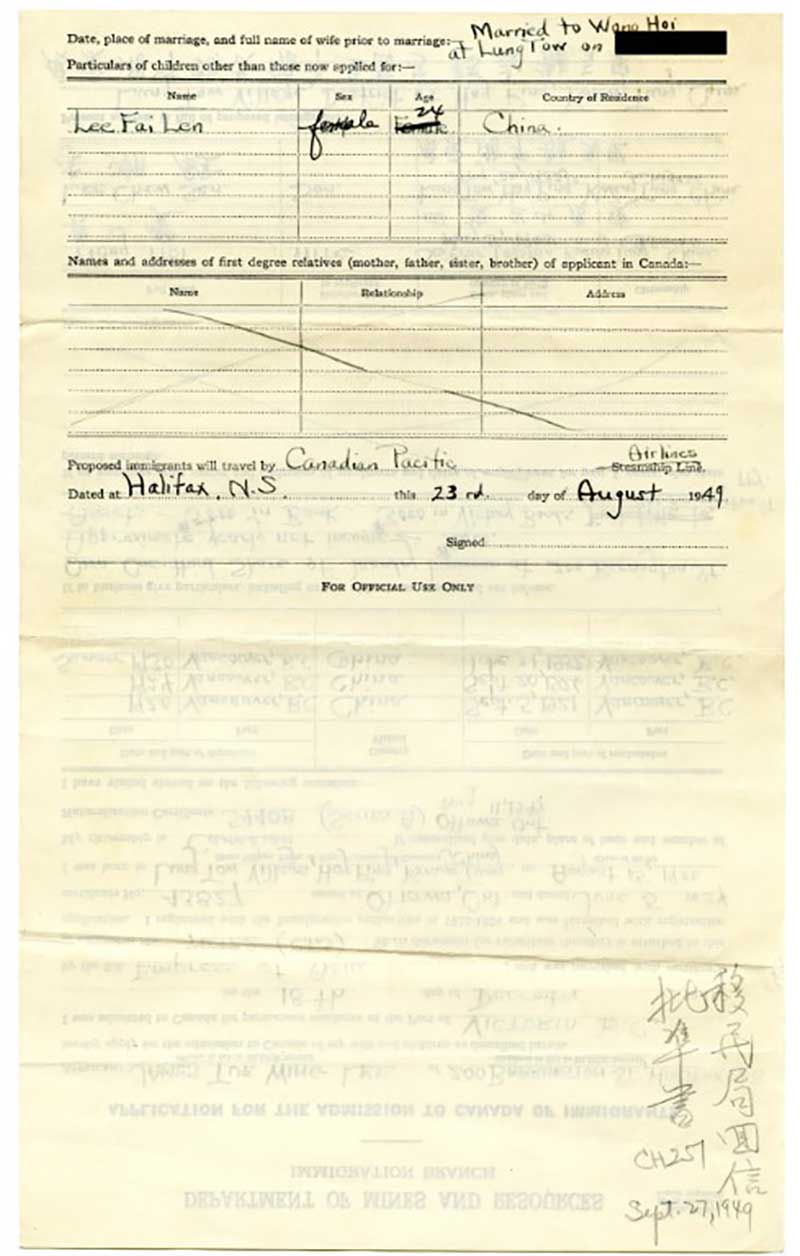

After the repeal of the Chinese Immigration Act, 1923, Chinese Canadians applied for family reunification. This is James Lee's request to bring his wife Hoi and son Chew Sen to Canada, and shows his initial arrival in 1916 as well as returns to China in 1920, 1924, and 1930.

Credit: Donated by JJ Lee on behalf of James and Hoi Lee. (DI2021.48.34)

Striving for Fairness

The advent of the “Points System” in 1967 was explicitly an attempt to address the question of unfairness, discrimination, or malleability in the admissibility of immigrants.[35] The significant change in major countries of origin in the years following the introduction of the new system signals a marked success. In 1968, just over 32 percent of immigrants came from Commonwealth countries, and not quite 5 percent came from China.[36] A decade later, the number of immigrants from India, Hong Kong, the Philippines and Jamaica was roughly equal to the combined total from Britain and the United States – a tremendous shift and diversification in sources of entry.[37] Divesting immigration practices of systemic racism was and remains a process: for example, in 1969, a Chinese community letter to the Allan MacEachen, the Minister of Manpower and Immigration, commended the advances in equitable policy for admission but pointed out remaining discriminations in medical examination practices.[38]

Apology and Redress

In 2006, the Prime Minister Stephen Harper issued a formal apology for the Head Tax and other immigration restrictions, including the exclusion era, 1923-1947. Harper stated “For over six decades, these malicious measures, aimed solely at the Chinese, were implemented with deliberation by the Canadian state…This was a grave injustice, and one we are morally obligated to acknowledge.”[39]

Redress included payments of $20,000 to those who paid the Head Tax, or to their spouses if they were deceased. It also included a phased investment of millions of dollars to bring forward commemorations of Ukrainian and Italian internment experiences, Chinese Canadian exclusion, and histories of the refusal of SS Komagata Maru and MS St. Louis.[40]

Conclusion

The Chinese Immigration Act, 1923 was part of a larger, continuous thread of anti-Asian policies and attitudes in Canada. The 1947 repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act still left many obstacles in place to bar Chinese immigrants. Those barriers were resolved over several decades; in recent years, Asian countries including China have been at the top of the list as countries of origin for Canadian immigrants.[41] However, a massive increase in anti-Asian hate crimes in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic is a cautionary note that, a full century after the implementation of the Chinese Exclusion Act, the same prejudices still operate in Canadian society.[42]

- Library and Archives Canada, Statutes of Canada, An Act Respecting Chinese Immigration, 1923, Ottawa: SC 13-14 George V, Chapter 38, available via “Chinese Immigration Act, 1923 | Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21,” accessed March 10, 2023, https://pier21.ca/research/immigration-history/chinese-immigration-act-1923.↩

- Patricia E. Roy, A White Man’s Province: British Columbia Politicians and Chinese and Japanese Immigrants, 1858 - 1914, Reprinted (Vancouver: Univ. of British Columbia Press, 1990), 4–7; On the construction of "Chinatown," see Kay Anderson, Vancouver’s Chinatown: Racial Discourse in Canada, 1875 - 1980, (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1995). ↩

- Kornel Chang, “Enforcing Transnational White Solidarity: Asian Migration and the Formation of the U.S.-Canadian Boundary,” American Quarterly 60, no. 3 (2008): 671, https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.0.0027.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, Report of the Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration, Report and Evidence, 1885, 1.↩

- Patricia E. Roy, “The Preservation of the Peace in Vancouver: The Aftermath of the Anti-Chinese Riot of 1887,” BC Studies 31 (Autumn 1976): 44–59.↩

- W. Peter Ward, White Canada Forever: Popular Attitudes and Public Policy Toward Orientals in British Columbia (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2002), 61.↩

- Ward, 67–71.↩

- Laurier to MacPherson, 27 Aug 1907, Laurier Papers, quoted in Ward, 67.↩

- Roy, A White Man’s Province, 203–4.↩

- F.J. McEvoy, “‘A Symbol of Racial Discrimination’: The Chinese Immigration Act and Canada’s Relations with China, 1942-1947,” Canadian Ethnic Studies 14, no. 3 (1982): 25. The future Prime Minister of Canada, William Lyon Mackenzie King, was responsible for many elements of the response of the federal government around this issue, including reports on the 1907 Vancouver riot and on Asian immigrant labour, as well as the unsuccessful quota negotiations with China.↩

- Laura Madokoro, “Family Reunification as International History: Rethinking Sino-Canadian Relations after 1970,” International Journal: Canada’s Journal of Global Policy Analysis 68, no. 4 (December 2013): 592–94, https://doi.org/10.1177/0020702013511192.↩

- Julie F. Gilmour, “H. H. Stevens and the Chinese: The Transition to Conservative Government and the Management of Controls on Chinese Immigration to Canada, 1900-1914,” The Journal of American-East Asian Relations 20, no. 2–3 (2013): 176, https://doi.org/10.1163/18765610-02003007. Gilmour engages effectively with the problems of engaging anti-Asian immigration in British Columbia both through an individual biography and via handling the population as an undifferentiated whole.↩

- H.H. Stevens, “The Oriental Problem” (Unknown, c 1911), 16, https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.98509/1. It appears that this pamphlet is a consolidation of previously-published material, and the dating is approximate, based on a reference in the text to Justice Murphy’s investigation of Chinese immigration.↩

- Patricia E. Roy, “British Columbia’s Fear of Asians,” Histoire sociale / Social History 13, no. 25 (1980): 164–65.↩

- Isabel Wallace, “‘Hindus,’ Hookworm, and the Guise of Public Health Protection,” BC Studies 178 (Summer 2013); also Library and Archives Canada, Immigration Branch fonds, RG 76, Vol 584, File 820636, “Hon. Frank Oliver, Minister of the Interior, Ottawa, Ont. Prevalence of hook worm among Hindus applying for admission to U.S. and among the Negroes (Blacks) of the U.S.”↩

- Library and Archives Canada, Immigration Branch Fonds, RG 76, Vol 584, File 820636, ‘Hon. Frank Oliver, Minister of the Interior, Ottawa, Ont. Prevalence of Hook Worm among Hindus Applying for Admission to U.S. and among the Negroes (Blacks) of the U.S.,’ Dr. P.H. Bryce to Dr. G.L. Milne, Ottawa ON, 28 December 1911, accessed March 21, 2023, https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c10658/225. Bryce closed his letter with permission to carry on with the necessary examination, although from his dry tone it is possible he thought this might be its own obstacle, as comprehensive screening for hookworm would require a significant capacity for secure and verifiable stool examinations.↩

- Patricia E. Roy, The Oriental Question: Consolidating a White Man’s Province, 1914 - 41 (Vancouver: Univ. of British Columbia Press, 2003), 73–77.↩

- Jin Tan and Patricia E. Roy, The Chinese in Canada, Canada’s Ethnic Groups 9 (Ottawa: Canadian Historical Assoc, 1985), 13.↩

- Peter S. Li, The Chinese in Canada, 2nd ed (Toronto ; New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 90–91.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, Statutes of Canada, An Act Respecting Chinese Immigration, 1923, Ottawa: SC 13-14 George V, Chapter 38, available via “Chinese Immigration Act, 1923 | Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21.”↩

- Library and Archives Canada, Citizenship and Immigration fonds, RG26, Vol 87, unnumbered file “Orders-in-Council, Immigration Branch, 1940,” “P.C. 7722-1940,” December 31, 1940.↩

- James W. Morton, In the Sea of Sterile Mountains: The Chinese in British Columbia, 1st paperbound ed (Vancouver: J.J. Douglas, 1977), 252.↩

- Li, The Chinese in Canada, 96.↩

- Stephanie Bangarth, “‘We Are Not Asking You to Open Wide the Gates for Chinese Immigration’: The Committee for the Repeal of the Chinese Immigration Act and Early Human Rights Activism in Canada,” Canadian Historical Review 84, no. 3 (September 1, 2003): 396, https://doi.org/10.3138/CHR.84.3.395.↩

- Patricia E. Roy, The Triumph of Citizenship: The Japanese and Chinese in Canada, 1941-67 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2007), 172–75.↩

- Roy, Triumph of Citizenship, 269–79. At the time, politicians and community advocates recognized that arbitrary immigration restrictions would backfire, pushing people into fraudulent representations or illegal entry and so reduce effective control over entries. For a detailed contemporary of this discussion, see Efrat Arbel & Alletta Brenner, Bordering on Failure: Canada-U.S. Border Policy and the Politics of Refugee Exclusion (November 2013: Harvard Immigration and Refugee Law Clinical Program, Harvard Law School), accessible at https://commons.allard.ubc.ca/fac_pubs/14/.↩

- See, for instance, Beth Lew-Williams, “Paper Lives of Chinese Migrants and the History of the Undocumented,” Modern American History 4, no. 2 (July 2021): 109–30, https://doi.org/10.1017/mah.2021.9.↩

- Peter Nyers, “The Regularization of Non-Status Immigrants in Canada: Limits and Prospects,” Canadian Review of Social Policy 55 (2005): 110.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, Citizenship and Immigration Fonds, RG26. Vol 99, File 3-15-1, ‘Immigration Regulations and Correspondence,’ Confidential Memorandum to Cabinet regarding proposed revision of the Immigration Act, unattributed and undated. It appears to be created on behalf of the Minister of Immigration and based on the content, is likely from the late summer or early fall of 1960. As present in this archival file, the memorandum extends to 17 pages but is incomplete.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, Citizenship and Immigration Fonds, RG26. Vol 99, File 3-15-1, ‘Immigration Regulations and Correspondence,’ Director of Immigration to Deputy Minister, Ottawa ON, 20 January 1961.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, Citizenship and Immigration Fonds, RG26. Vol 99, File 3-15-1, ‘Immigration Regulations and Correspondence,’ Director of Immigration to Deputy Minister, Ottawa ON, 20 January 1961, attachment “Summary of Discussions Regarding Admissibility,” 4. Emphasis in original.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, Citizenship and Immigration Fonds, RG26. Vol 99, File 3-15-1, ‘Immigration Regulations and Correspondence,’ Director of Immigration to Deputy Minister, Ottawa ON, 20 January 1961, attachment “Paper B.”↩

- Library and Archives Canada, Citizenship and Immigration Fonds, RG26. Vol 99, File 3-15-1, ‘Immigration Regulations and Correspondence,’ Director of Immigration to Deputy Minister, Ottawa ON, 20 January 1961, attachment “Summary of Discussions Regarding Admissibility,” 5.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, Citizenship and Immigration Fonds, RG26. Vol 99, File 3-15-1, ‘Immigration Regulations and Correspondence,’ Director of Immigration to Deputy Minister, Ottawa ON, 20 January 1961, attachment “Paper C.”↩

- Library and Archives Canada. ‘Immigration Act, Immigration Regulations, Part 1, Amended’ RG2-A-1-a, Vol 2380, PC1967-1616, August 16 1967, accessed March 24, 2023, https://pier21.ca/research/immigration-history/immigration-regulations-order-in-council-pc-1967-1616-1967. There were some teething problems: for instance, 15 of a required 50 points were determined by the nebulous assessment of an immigrant’s “personal suitability.” This required intervention: in February of 1968, the ADM (Immigration) distributed a guide to assist in standardizing the use of those points. See Library and Archives Canada, Immigration Branch fonds, RG 76, Vol 938, First Immigration Manual, Binder 18, “Clarification on Personal Suitability Points.”↩

- Canada, Manpower and Immigration, Immigration Statistics/Immigration Statistiques : 1968 (Ottawa: Manpower and Immigration, 1968), 2.↩

- Canada, Employment and Immigration, Immigration Statistics/Immigration Statistiques : 1978 (Ottawa: Supply and Services Canada, 1980), 2.↩

- Library and Archives Canada, R11939 Box 28 File 12, Chinese Community of Toronto, Montreal, Hamilton, Sarnia, Burlington, Orillia & Peterborough, “Memorandum to the Honourable Allan J. MacEachen, Minister of Manpower & Immigration,” June 16, 1969, 1. The author would like to thank Daniel Meister for sharing this fascinating document.↩

- Employment and Social Development Canada, “Prime Minister Harper Offers Full Apology for the Chinese Head Tax,” news releases, June 22, 2006, https://www.canada.ca/en/news/archive/2006/06/prime-minister-harper-offers-full-apology-chinese-head-tax.html↩

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, “Evaluation of the Historical Recognition Programs,” assessments, April 15, 2013, https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/reports-statistics/evaluations/historical-recognition-programs.html.↩

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, “2022 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration,” November 1, 2022, 50, https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/publications-manuals/annual-report-parliament-immigration-2022.html.↩

- Vanessa Balintec · CBC News ·, “Asians ‘Tired,’ ‘frustrated’ as Study Shows Hate Is on the Rise in Canada | CBC News,” CBC, April 3, 2022, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/2-years-into-the-pandemic-anti-asian-hate-is-still-on-the-rise-in-canada-report-shows-1.6404034.↩