Source: Library and Archives Canada/RG18, vol. 3567, file c315-36-3. Page 119/136

Many Canadian cities have a Chinatown. There are neighbourhoods called Greektown, Little Italy and Little Portugal.

In pre-war Vancouver, the Powell Street area in the Downtown Eastside was home to thousands of Japanese Canadians. This included first-, second-, and third-generation Canadians. People from Japan had begun to immigrate to British Columbia in the late 1800s. In the face of anti-Asian sentiment, they put down roots, started businesses and saved to buy land and establish their families.

Why isn’t it universally known as Japantown now?

Uncovering the answer reveals a history of 20th-century anti-Asian sentiment and policy. It is a history of displacement, dispossession, and dispersal.

Existing anti-Asian sentiment

Japanese Canadians in BC faced hostility. In 1907, a parade was held by the Asiatic Exclusion League, a group which included the city’s Mayor and which sought to stop Asian immigration to Canada. The League promoted the idea that immigrants from Asia were driving down the cost of labour. The parade turned into a riot. Windows of homes and businesses owned by Chinese and Japanese Canadians were smashed.

Still, the community continued to deepen its roots, not only in Vancouver but elsewhere in BC.

The reasons for discriminating against Japanese Canadians evolved. Japan was growing as a military power; in 1931, its invasion of Manchuria (China) raised concerns that it could attack the Pacific coast. This gave Canadians a new excuse to suspect their neighbours. In the late 30s, plans were prepared to seize the boats of Japanese Canadians in the event of war. The provincial government created a list of Japanese Canadians with business licenses. In 1940 the federal cabinet struck a special committee to report on "the oriental situation" in British Columbia.

Internment

Following the bombing of Pearl Harbour in 1941, Canada declared a state of war with Japan. At this point, things start to move fast. New policies affecting Japanese Canadians are enacted, regardless of citizenship or how long individuals have been in Canada. Overnight, Japanese Canadian children are no longer welcome in school. Fishing boats owned by Japanese Canadians are seized. Within days, an office of the Custodian of Enemy Property opens in Vancouver. Within weeks, the Canadian government passes a law to remove Japanese Canadians from a 160 km “protection zone” on the Pacific coast. Men and women, infants and the elderly are put into internment camps, living in tents or shacks.

Prime Minister Mackenzie King publicly states that "persons of Japanese race, who are Canadians either by birth or by naturalization, and Japanese nationals resident in Canada will be justly treated. Their persons and property will receive the full protection of the law." Privately, however, he agrees with the views of a Chinese diplomat that people of Japanese heritage should not be trusted- that they “would be saboteurs and would help Japan when the moment came."

Internment lasts throughout the war. Restrictions on movement of Japanese Canadians remain in force until 1949.

Dispossession

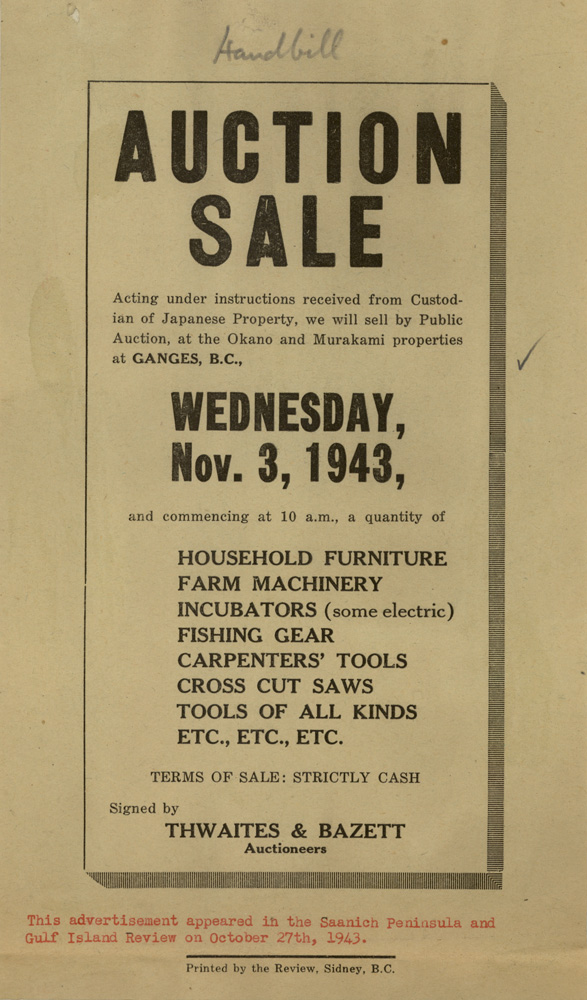

The government promised to care for and return seized property once internment ended. Instead, over the next several years, properties were allowed to deteriorate. Despite protests from their owners, land and homes were forcibly sold off for less than market value. Personal items were sold at auction. The buildings of the Powell Street neighbourhood, the heart of Vancouver’s Japanese Canadian community, now had new owners.

Source: Library and Archives Canada/e011167565

Dispersal

In March 1945, the Canadian government pressured Japanese Canadians in BC to either move east of the Rockies and begin a new life away from the coast or be put onto a boat to be sent permanently back to Japan. Some accepted exile. Some moved east. Few returned. The Powell Street area was transformed.

Reclamation?

In 1977, the annual Powell Street Festival launched to celebrate Japanese Canadian arts and culture. More recently, a group called Heritage Vancouver asked that the neighbourhood be designated “Japantown”, a heritage conservation area. Others resist the name, including members of the Japanese Canadian community. The Downtown Eastside is an area with more than its share of poverty and complex social challenges. The creators of the 360 Riot Walk, an interactive walking tour of the 1907 Anti-Asian Riots in Vancouver, are concerned that the heritage designation coincides with efforts to gentrify the area and in doing so, displace its current residents, repeating past wrongs.