Wall of Service

Column

14

Row

23

I left Canada as Staff Sergeant, and two and a half years later came back to Pier 21 as a Private. Quite a slacker, you'd think! So, there's a story.

Why in the world would any young woman of 22 join the army, especially in the first years of World War II?

I did! I'm not sure why; something different; adventure; a good solid job; smart uniforms or, because a long time friend of mine had joined and suggested that it was a great life. She told me there were many interesting people, jobs, men. Quite a change from working in a bank and, our country was at war. I joined, November 11, 1941 and remained until December 11, 1945.

I requested to be a driver and loved the job. Basic training took place at the old University Avenue Armories in Toronto. I drove Staff cars, jeeps (one of which I drove up and then down the steps at the Old City Hall in Toronto during a Victory Loan gathering of thousands of people). I drove large army trucks that we learned to operate in convoy. I always seemed to have trouble with the gears. This was long before automatic transmissions and power steering. I became a motor mechanic; I took a course, and got 10 cents a day more! I used to give driving lessons to kids coming into Ordnance, and some of them, I'd think, "If I live through this, I'll live through the war!"

I was then attached to the Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps and later I was loaned to the Public Relations section where I was involved in many public events such as broadcasting, celebrations at City Hall, movie stars and mock battle events at Riverdale Park (Toronto).

I met people of interest and appeared in many publicity photos in newspapers, magazines and brochures; and, as a photographer pointed out to me, "Not because you are that good looking, but because you are here."

I drove many out-of-town trips in Staff cars or delivered mail in a panel truck to Camp Borden (west of Barrie, Ont.), drove Officers to important events. We never had to be in at a certain time at night. We could always say we were off driving someone.

During that time Holland, Belgium and France had all fallen to the Germans. The Canadians were heavily involved in the famous Dieppe Raid, in particular the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry. Some of the C.W.A.C. girls' husbands, brothers and friends were in this raid, bringing the war close to us.

Having worked in and around Toronto for over a year, I decided I would like to go overseas. I wanted to be more useful in the war effort and I wanted to see England. Remember, in those days, the only way to get to England was by ship and usually only if you were posted overseas.

There was no commercial air traffic and passenger ships were now Troop Ships. There was another reason too; already over there, waiting for me, was a special boy.

By now, I was Sergeant. There was an old saying; if you had trouble with a private you gave them a stripe, and then they had to take responsibility. That's why I rose up in the ranks. I had too much to say. So first I was a Lance Corporal, then a Corporal, and still a driver. When I became Sergeant I did more office work, but still drove a Staff car.

I was accepted on the third overseas draft. I convinced the officials that I would be capable of taking over the job of a Quartermaster in the Quartermaster Stores in England. The working world, at that time, was still mostly a man's world and we women were going there to replace men in non-combat jobs. As women we had to convince the officials we were smart and disciplined enough to hold responsible jobs. I was made Staff Sergeant to take my place overseas.

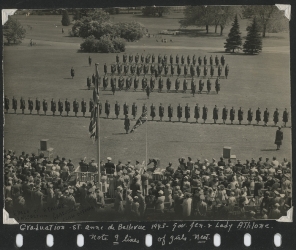

We were on our way! I went home to Orillia on a fast leave and left Toronto in March, 1943 to spend four months training at Ste. Anne de Bellevue in Quebec.

In July, 1943 we arrived at Pier 21 from St. Anne de Bellevue by train. I remember getting off the train and going towards this big building. It was a rather a barn of a place. Of course, I was coming from a farm, so to me, it looked like a barn. We went in and up to the second floor, and crossed a gangway from there to get on the huge Queen Elizabeth ship - amongst 17,000 troops, all men except for 139 C.W.A.C. and a few nurses. And of course all the men were calling out and waving. They were quite pleased to see these women coming aboard! But we were sent up to an upper deck and kept to ourselves. I think they had trouble, once before, with women partying with the men on another ship, so we were kept separate.

We left for England without an escort. The Queen Elizabeth was too fast for subs to catch. (But for 500 miles of the voyage a minesweeper stayed several miles ahead of us. Unknown to me, my cousin was on that minesweeper.) Our cabins, originally designed for two or four, were re-designed to hold 21 wooden bunks three tiers high, so close together with hardly room to roll over, and one narrow walkway and one toilet, which was not great for sea-voyage ailments. We had two meals a day, in order to give room to the great numbers of troops being fed.

In four or five days we glided at sunset up the Clyde Estuary in Scotland. People lined the banks, waved and cheered, and our Royal Hamilton Light Infantry band played Scottish music. It was the most peaceful sight one could imagine, so it was hard to believe this country had been at war for almost four years.

Well, I was Staff Sergeant, Acting Quartermaster, for the 139 C.W.A.C. who went overseas. And it was no romantic thing! They said, "You're not going to London. You're going to No. 1 Static Base Laundry and if you have any idea you're going anywhere else you're crazy!" Most C.W.A.C. in England had been sent to London to work in military headquarters. Our unit did hospital laundry. It was a very essential job because there were several hospitals all in that area. It was Camp Borden, Hampshire, near Aldershot. We C.W.A.C. were attached to the Royal Canadian Army Service Corps. The men had a Quartermaster and we had a Quartermaster. The men always had to be in charge, so I was called Acting Quartermaster.

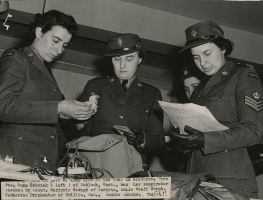

The 139 girls came from all over Canada, and they did jobs connected with the laundry. My job was to do with the girls' clothes. I had to handle all the clothing and equipment, uniforms, battle dress, shoes, skirts, underclothing, stockings, all the essentials. I was one and a half years in England.

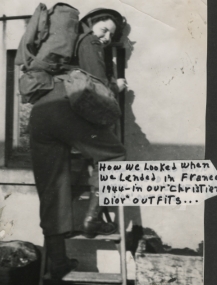

But, I wanted to get to the Continent. I tried to get a transfer to France several times and, no go. Then, in September 1944, out of the blue sky, I was told I could go if I wanted to revert to Private. I thought it over and decided, yes! After all, I wasn't going to be happy until I got there, now that I was that close. I went to work in Casualty Records, attached to the 2nd Echelon, Canadian Section, 21st Army Group, B.W.E.F. We landed in France on Juno Beach, at one of the floating docks, called The Mulberry, set up for D-Day, and traveled into Belgium. We ended up 10 miles from the front lines, in Antwerp.

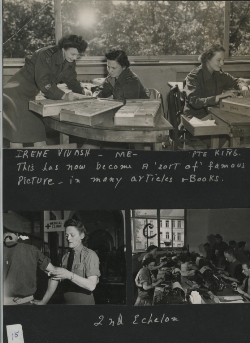

We ran a card index system of the posting of every man and woman in the Canadian army on the continent. It had to be kept up to date 24 hours a day. It was rather interesting, and rather sad. If there were a lot of injuries from one unit we knew who was fighting where. We heard who was transferred to hospital, or another unit. We sent on information for notices back to Canada, information that was delivered to next of kin. We gave information to the post office, if they were looking for a correct address. We recorded information sent from the field. Quite often men phoned in from the front lines, using the "Able, Baker, Charlie" system to give us the information and correct spelling. You had to be completely exact. Of course, the boys had quite a different code for A-, B-, C-. I'd have to say, "This is a woman on the line!"

Second Echelon was a general organizing section/clearing house. There were 10 or 15 in our office, not just women. Men worked in casualty records, too, men who hadn't passed the medical exam. In all there were about 1,000 people working in our offices, handling casualty records, typing telegrams back to Canada, dealing with men's effects, etc. When we had to move we had to pack up everything, desks and all, in two days.

At first, V1 rocket bombs, which we called Doodlebugs, were falling in Antwerp, then V2s. The V2s were faster than sound. You didn't hear anything coming, just felt the explosion. There was very little quiet time between bombs exploding. About every few minutes something would fall. One bomb dropped across the road from us at work. I was looking out the window and had happened to turn around, so I was hit in the back of the head by a plate glass window. Everyone else shot under thier desks. Half our office was billeted out of Antwerp, in Hoboken, so that if we were hit, someone could keep the service going. I moved to Hoboken, a suburb of Antwerp, thinking if the card index office were hit, we wouldn't have anything to do, anyway.

At the end of December, 1944 we were evacuated to Aalst, 25 miles southwest of Antwerp, during the Battle of the Bulge. We stayed there until we were moved to Lemgo, Germany, in July, 1945, were we stayed until October, 1945.

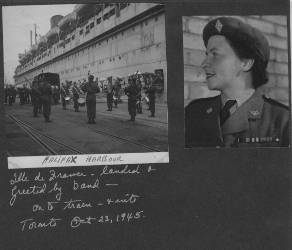

I returned from Southampton, England, to Pier 21 on the Isle de France and we were greeted by a band in Halifax Harbour. We got onto the train, and we were into Toronto on October 23, 1945. As my birthday is October 24, I had written to my mother saying that perhaps I would make my second arrival on October 24 again, at Edgewood Farm, our home.

I had learned a lot. To come from a close-knit family group, and to all at once find yourself living and working with people who lived in the same country but came from a much different type of world! They came from ranches on the prairies, mountains in B.C., from Vancouver Island, Newfoundland, the Maritimes and Quebec - all so different yet all involved for the same reason, to help our country and defeat Nazism. I had never been exposed to the ways of life all these people came from, and I soon realized that my way was not theirs. The community I grew up in was all English, and everyone did everything the English way. At first I tried to pick and choose who I'd be friends with, but I found out very fast that the girls with the broadest vocabulary were some of the best friends you ever had. I soon learned to make the most of it. The ones who became my friends were the ones who spoke their minds and didn't mind when I spoke mine. I learned to live that way. But when I returned back to civilian life, I found that is not the way they lived there. There was a long time of adjustment.

I was discharged December 11, 1945. I was back to Private, a noisy one, but a Private.

Catherine K. Drinkwater,

Pte., L.Cpl., Cpl., Sgt., Staff Sgt. Acting Quartermaster, back to Pte.

C.W.A.C. - W2092

This information is compiled from conversations with Catherine Drinkwater in January, 2007, from parts of her letters from overseas, and from her "Introduction" to her book, Letters to Edgewood Farm: From a Canadian Girl in World War II, published in 2002 by Bunker to Bunker Publishing, Calgary, Alta., and edited by Bonnie Rourke, ISBN 1-894255-21-6.

Catherine, born October 24, 1918, lives at Edgewood Farm, just outside Orillia, Ontario, a farm held by five generations of her family. Her great, great grandfather, the Reverend George Hallen, was installed at a local church in 1834, having moved from England with his wife and ten children. Catherine's family is a family of journal writers and local historians. When she began writing letters home from England, and then the Continent, her mother saved them, her sister Joan typed them, and they created albums with the many photos that Catherine, who lists photography among her many accomplishments, had taken. The letters and photos from these albums are the basis of her book, Letters to Edgewood Farm. The original albums are now held by the Huronia Museum in Midland, Ontario, along with other significant contributions from the family. The World War II photos that accompany this article are taken from Catherine's collection and from her book, a copy of which has been donated to the Pier 21 museum. The book is available from the Huronia Museum, 549 Little Lake Park, P.O. Box 638, Midland, ON L4R 4P4, 705-526-2884, info@huroniamuseum.com.

Susan Charters

Orillia, 2007