Sobey Wall of Honour

Column

200

Row

14

The following are edited sections of Susan Stein’s memoir. They pertain to the family leaving Czechoslovakia fourteen months after Winston Churchill’s “Iron Curtain” speech and making their way west through Europe and to their life in Canada.

ONCE UPON A TIME

Fairy Tales start with these words and looking back over the many years of my life, they are the right ones to start writing my memoirs.

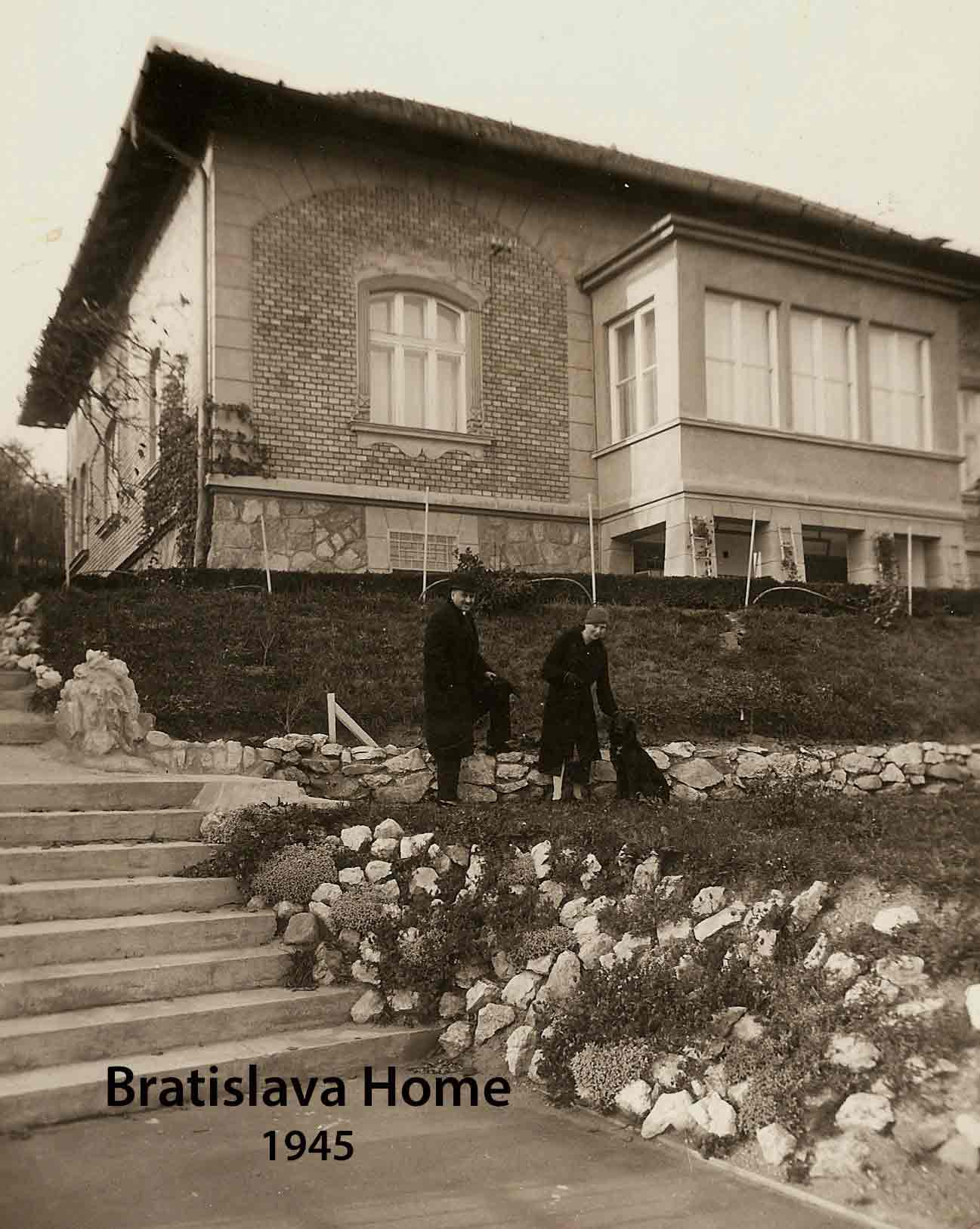

Born and raised in Bratislava, then part of Czechoslovakia, a republic founded after WW I, we were the dear twin daughters of doting parents. Our house, up on a hill, designed by Dad, was surrounded with fruit trees and gardens. Early in the morning, before going to work, Dad weeded, pruned and planted. We had to help in order to learn manual work and to instil a love for nature. He succeeded. That discipline greatly helped many years later when we began a new life in Canada.

My father was a civil engineer building highways across the country. He travelled extensively, inspecting quality and progress. Even away from home, his orders and the discipline instilled in us were strictly obeyed. We were pretty well behaved most of the time not counting putting caterpillars down grandmother's neck and refusing to eat spinach or other food supposedly good for you. We were treated as little princesses, with dresses made by a seamstress or purchased in Vienna at a famous children's clothing store along with rings, necklaces and a bracelet with charms. Above all we also had to have manners: curtsy when greeting guests, kissing Grandma's hand, holding knives and forks properly and never, never slurping soup, never slouching at the table and always waiting until our father or the guests at the table started. Until age five we ate dinner earlier with our Nanny, because the regular dinner hour was only around 7 o'clock.

For holidays we went to the Tatra Mountains in Slovakia, to the Adriatic Ocean in Yugoslavia and Lake Balaton in Hungary. We stayed in luxury hotels and had to have perfect manners.

We took ballet lessons which I hated. I really liked fencing, taught by a German fencing master. I excelled, winning the bronze medal in the junior competition between Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Austria. We took dancing lessons in waltzes and foxtrots. Boys lined up one side, girls on the other. I felt awful and tried to hide in the washroom. I must admit I came to enjoy it and have loved dancing ever since. We also took piano lessons, which did not make me a concert pianist, but taught me to appreciate music, read notes and learn the great composers.

This idyllic life changed dramatically with the Nazi occupation making Slovakia a puppet state with Jozef Tiso as president. Tiso was a Catholic priest and because of his collaboration with the Nazi regime, was excommunicated by the Vatican. Soon after, around 1938/39, the racial laws were introduced. First, all Jews who were not able to hide or emigrate, were rounded up and transported to Theresianstadt, one of the concentration camps. Jewish children were prohibited from attending schools and the Star of David had to be worn by all. Jewish properties were confiscated. They were put into ghettoes, and later rounded up during the night and shipped in box cars to Auschwitz.

Our father closed his office in Prague, concentrated on building and maintaining roads in Slovakia. After Germany attacked Poland, he also got involved in the clandestine operation of constructing fortifications along the border. This resulted in the Hlinka Guard (the Slovak equivalent of the Gestapo), after somebody had informed them of his activities, taking Dad away to jail. He was later released through the intervention of his friends in the government. The war went on and daily broadcasts from the fronts, controlled by German media, were all victories. Listening to the short-wave stations from England (a capital offense), we knew the situation in Africa and Russia and then about the invasion of Normandy. Etched in my mind is the evening June 6, 1944, when coming home after curfew, father, who was listening to the BBC gave me (the only time ever) a slap on my face for not obeying the curfew.

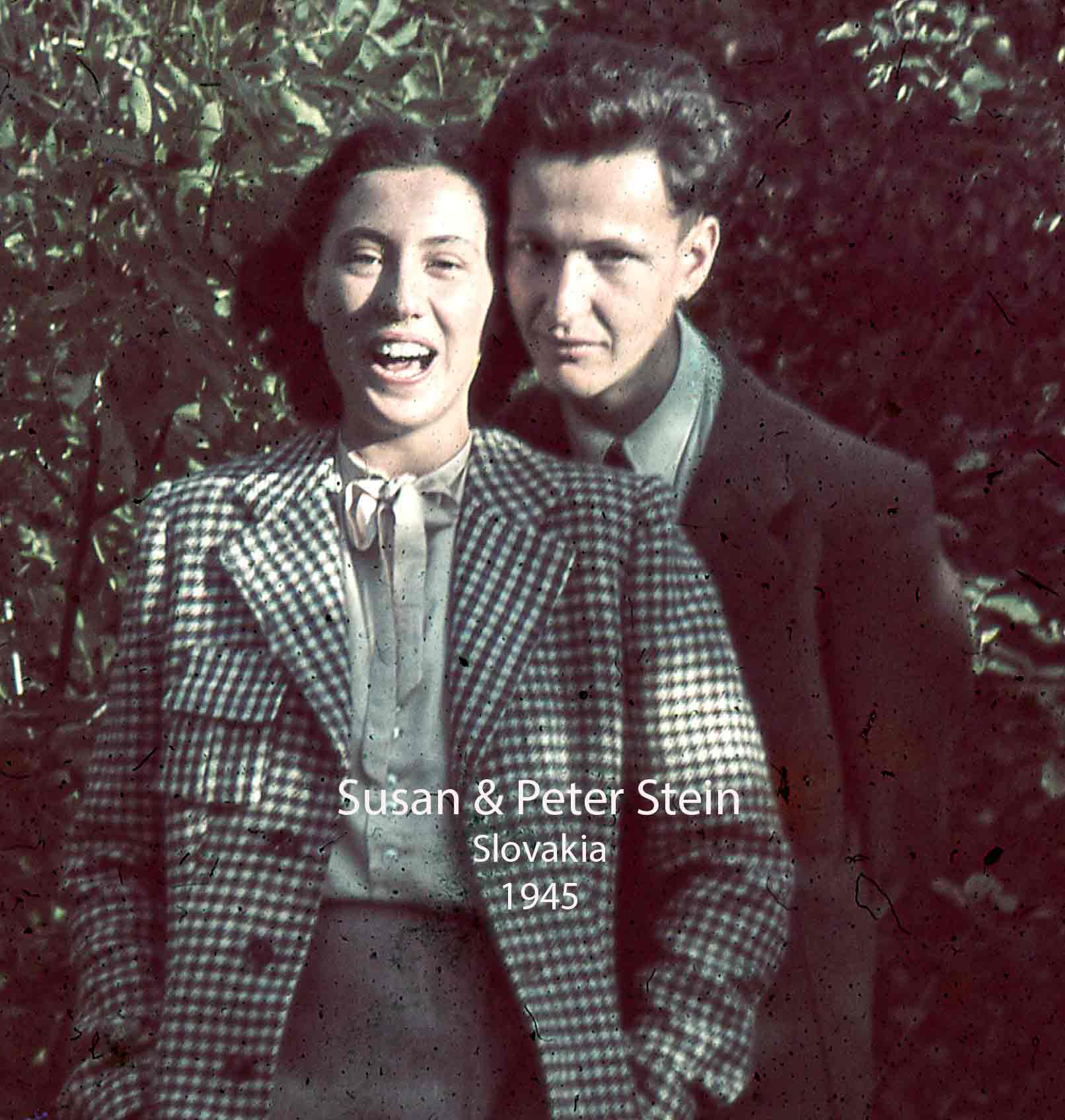

I first met my husband Peter, in winter on a bus to the ski slopes. Peter’s family owned Pivovar Stein, the largest brewery in Slovakia. Later, in the summer of 1943, Peter and I started to date. Very much in love, with the blessings of our parents, we married in September 1945.

After the war, my father founded a new company, rebuilding houses and roads in the Netherlands. The office was in The Hague and my parents spent weeks there. Instead of going to university, I got pregnant and on a snowy, winter day in 1947 Mike was born. Peter, after the death of his father, took over the management of the brewery. His brother Paul went to agricultural college to get ready for running the Stein barley and hops farm in Moravia. The future looked promising. As a young, well-off couple we led a pleasant life, enjoying parenthood, friends and holidays.

In February 1947, the Communists took power. The Czech president, Jan Masaryk was murdered by being thrown out of a window of Hradcany castle. My father returned from Holland. He told Peter to get out before the borders closed. Peter continued to work at the brewery, which was nationalized by the state, until he was told by the Worker’s Council he was no longer needed. I made a list of the most essential things to fit into three suitcases for our escape. The safest way (so as not to raise suspicion) was to drive to Hungary. From there go via Austria to Switzerland. Into a large wooden crate I put bedding, winter cloths and silverware, to be sent after us to Switzerland.

On May 1st, 1947, we left our homeland in a car driven by a brewery employee, decorated with flags for a national holiday. We crossed a bridge on foot to the Hungarian side. Trembling with fear, that the guard will not let us through, we walked with Mike in his stroller to the railroad station. After a two-hour train ride, we arrived in Budapest and from there we took another to Austria and from there to Switzerland. This was a harrowing experience. Austria was divided into three zones, Russian, American and British. At the Russian zone, armed soldiers boarded the train, went from compartment to compartment, taking some passengers off the train. When they came to us, I pointed to the sleeping baby and in Russian asked them to be quiet. They left without a word. On arriving in Switzerland, we were allowed to stay in Ascona, a very pretty tourist town. Peter knew that our Uncle Alexander always deposited money into foreign accounts and invested in bonds. He found the bank in Zurich and after explaining our circumstances and that Alexander Stein was dead and we were the beneficiaries of his will, the bonds were released giving us enough to live on while in Switzerland. Money had also been deposited in an English bank in London. Luckily, we gained access to that as well.

Where to now? The USA had a quota system and it would take perhaps years to be eligible. Australia was so far away. Our choice was Canada. To become a legal immigrant, the options were to work in a mine or a farm, or by purchasing land for farming. Peter contacted the Home Office in London, with our decision to purchase a farm. A gentleman from the Home Office arrived to interview us. Peter’s brother Paul, who had escaped by a different route, related the family's farming background. With the promise to deposit the funds for buying a farm with the Canadian Colonization Department (now IRCC), we obtained the documents to land in Canada.

On a cold November day in 1948 we boarded the ship Scythia in the French port Le Havre for the ocean crossing. It was no luxury ocean cruise, but a ship for displaced persons. That was all we could afford. The food was awful, the ocean rough. Despite the raging wind, I took Mike outside for fresh air and away from the crowded cabin and the smell and noise of people getting seasick everywhere. After ten long days we docked in Quebec City.

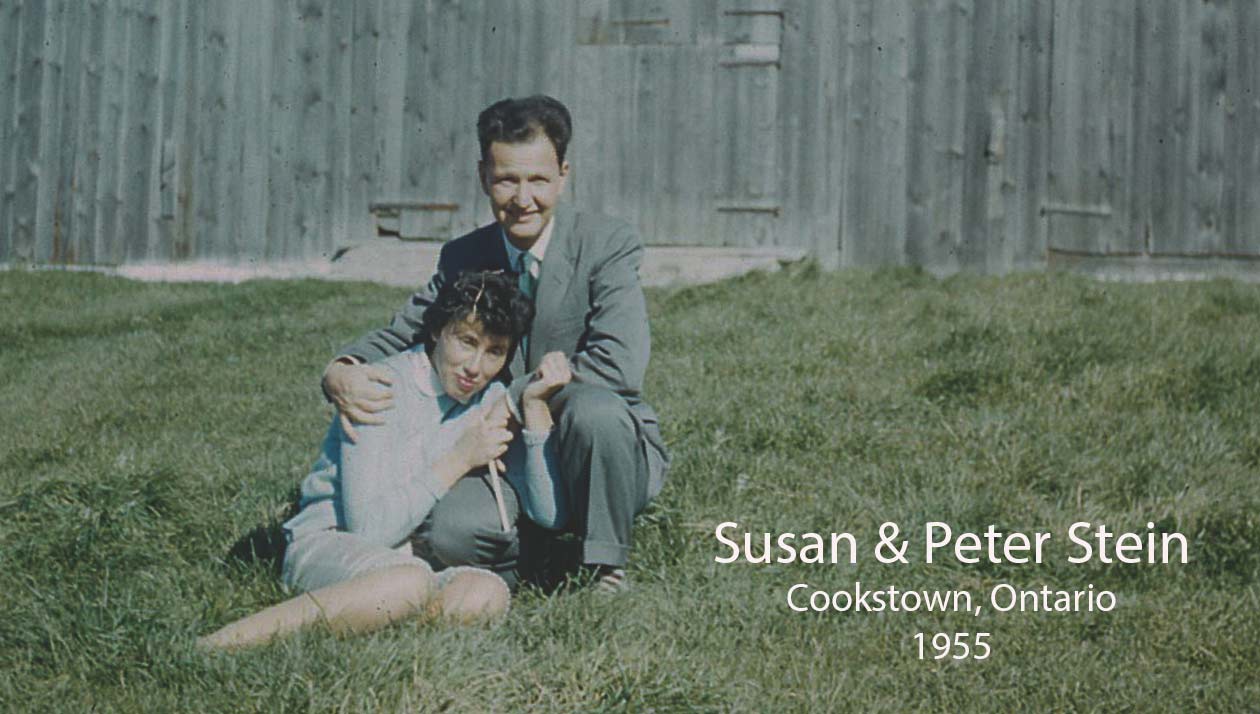

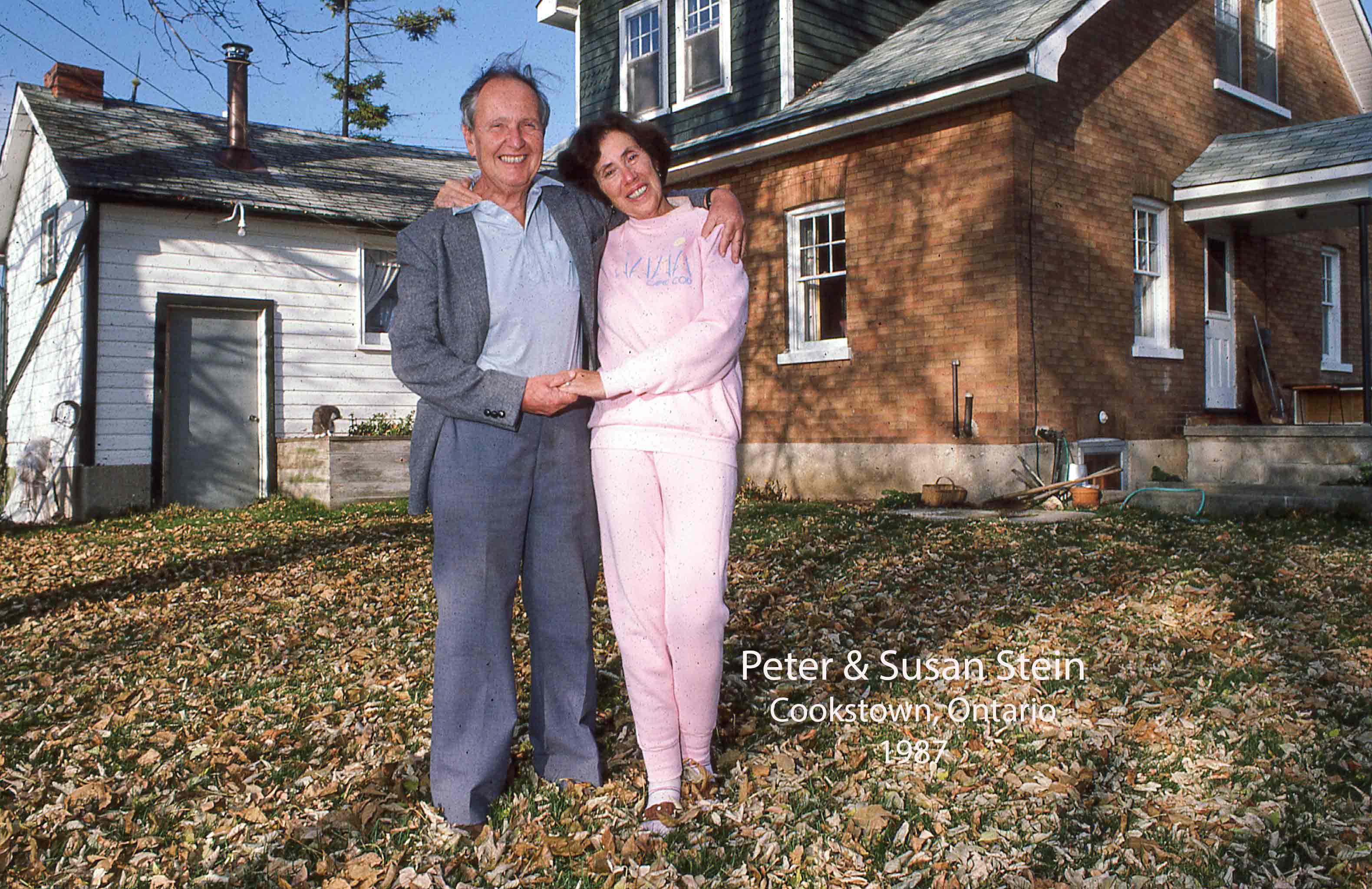

A boat train took us to Toronto where friends had arranged space in a rooming house on Selby Street. Peter and Paul, after contacting the Colonization Department, went to look for a farm. With them went a representative from the department, to make sure, that the farm being sold to us had the potential of making a living. The farm chosen, was in Cookstown, Ontario, had 100 acres of good soil, a lovely house with a bathroom, two bedrooms, a large kitchen with a wood burning kitchen stove. The deal closed on Boxing Day, 1948.

Meanwhile, to help ends meet and give me a little spending money, I found work at the Northcott Textile firm on Wellington Street. My wages: $25.00 per week. I will never forget our first Canadian Christmas. From work they took me to Eaton’s and Simpson’s Department Stores on Yonge Street, to see the decorated shop windows and to hear the singing of Christmas Carols during lunch break. They also invited me to the firm's Christmas party with turkey and all the trimmings, cake and punch. For a present I received a huge

box full of material for curtains, dresses, linen, the finest and warmest cloths and toys for Mike and for me a dresser set of brushes, mirrors and cologne. $25 dollars could buy a lot in those days.

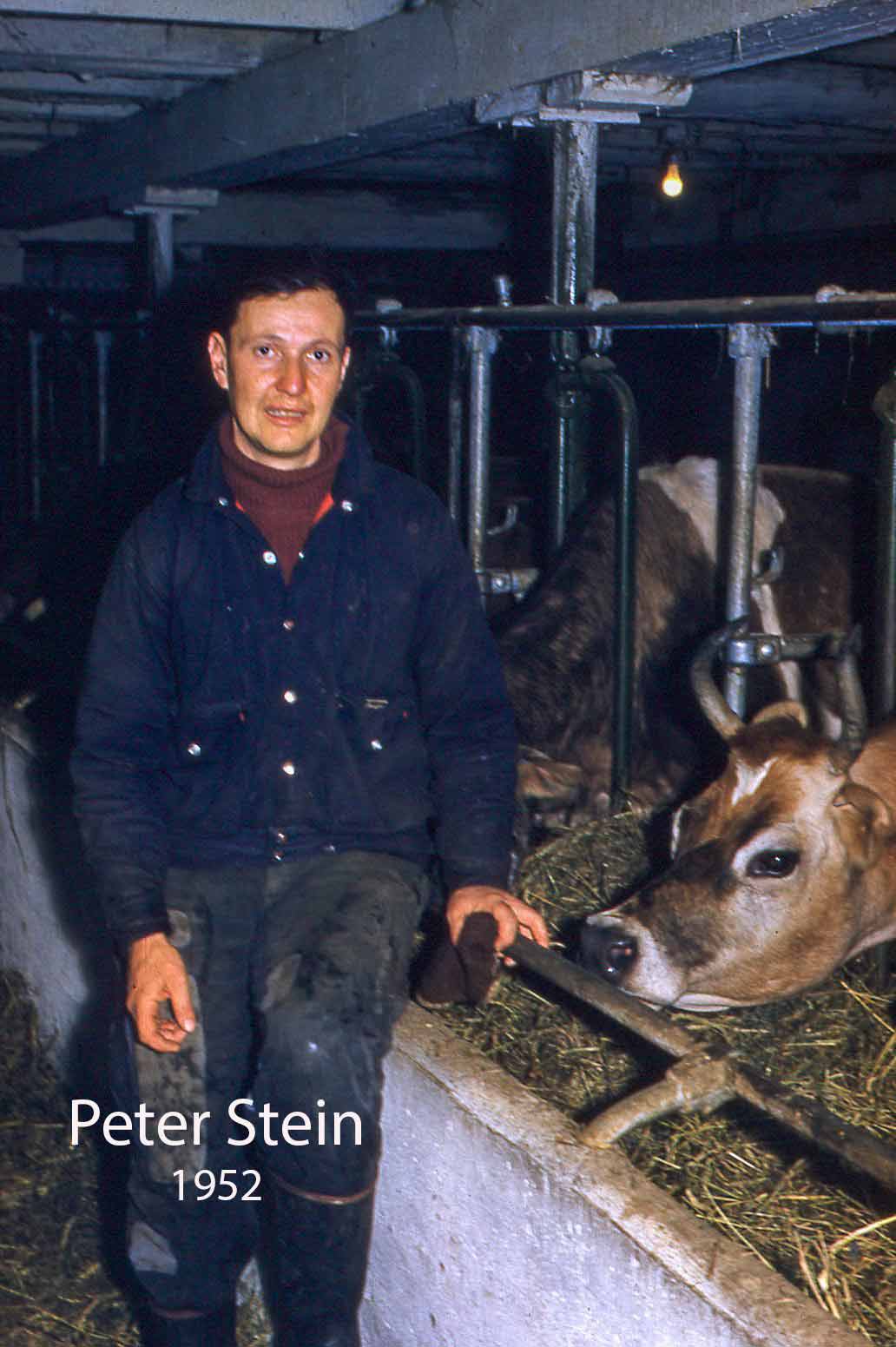

In January 1949 we moved to the farm. To make a living, it was decided to buy Jersey cows, whose milk was converted into cream and butter and sold to a dairy in the city. We learned to milk, clean the stable, drive a tractor, cut hay with a binder, plant wheat, oats and seeds for a permanent pasture. It was hard work, but rewarding and made us a part of the Cookstown community.

Good news came from my parents. The borders were open. So my parents, my sister, who graduated as pharmacist in 1947, her husband, also a pharmacist and their baby Peter joined us in Canada. To secure their immigration permit, we had to sign, that they will not be a burden to the Canadian government and that we will provide housing and food.

It has to be mentioned, that after living in Canada for 5 years, we were sworn in as Canadian citizens at a ceremony in the Barrie City Hall, presided by a judge and our friend and farming neighbour, Mr. Russell Draper as witness. After the ceremony he took us out to a steak dinner at the Queens Hotel in Barrie.

Note: I am Susan’s youngest son, Andy, Mike’s brother, and I have done this edit. There is much I had to leave out. By the mid 50s the farm was prospering. They had been embraced and supported by other farmers, neighbours and the United Church. They were thrilled with their adopted home. I distinctly recall a conversation with my parents, over the dinner table. There was a point in time that they couldn’t really identify but “they had become Canadian. They couldn’t imagine being anywhere else. Canada was their country, Canada was their home”.