Sobey Wall of Honour

Column

182

Row

13

Arrived as: Displaced person

Country of origin: Hungary

Date of entry: December 4, 1951

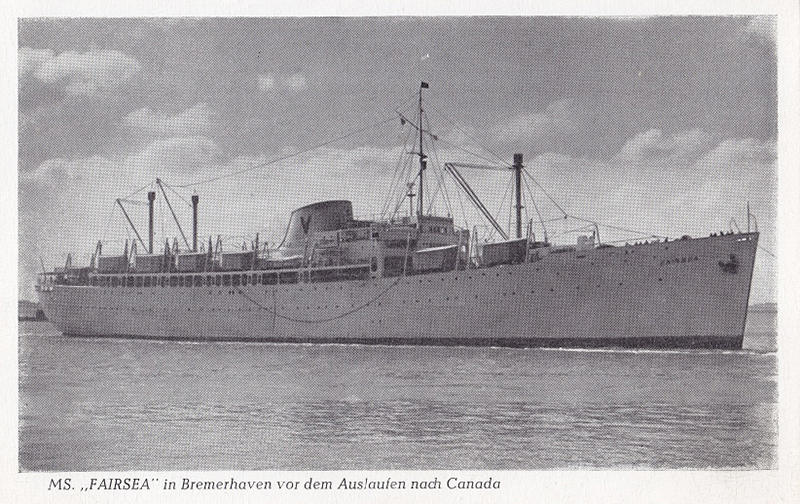

Ship name: Fairsea

Port of entry: Halifax

Age at arrival: 22

Your story:

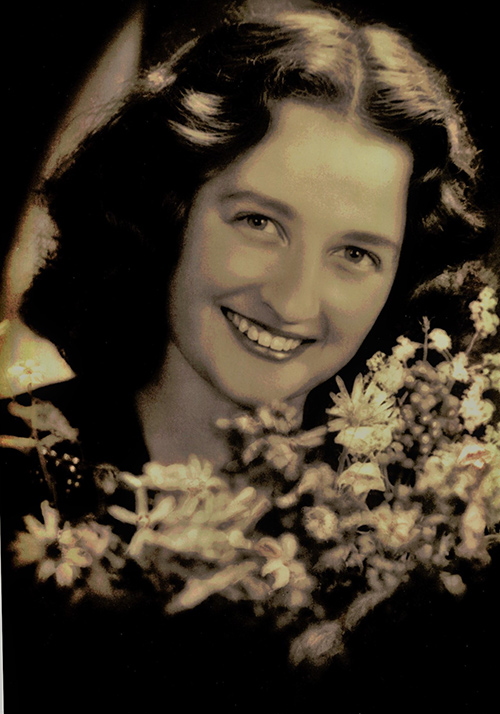

My mother was 22 years old when she arrived at Pier 21 on December 4, 1951 with her parents and her surviving brother and sister (Béla and Éva died before they left for Canada). In the years that followed, they compiled many daily tidbits of information, but unfortunately they never took the time to properly recount the story of their arrival in Canada.

All my mother told me was that she had been very sick during the crossing, and she still clung to the memory of the Weston bread she was given upon arriving. It was sweet-tasting, which for Europeans was supremely exotic. From Halifax they took the train to Montreal, where they settled and worked very hard to make a living and eventually buy a suburban house.

Unfortunately, the happy life to which they so aspired never fully manifested.

László, April 22, 1923 – August 17, 1963 (40 years old)

Lipót, August 24, 1891 – April 15, 1978 (86 years old)

Madgolna, December 27, 1927 – November 25, 1988 (60 years old)

Gizella Sandor, January 30, 1900 – April 10, 1992 (92 years old)

Márta, September 18, 1929 – November 8, 2011 (82 years old)

Because they never officially told their saga, I decided to write my own slightly romanticized version from the bits I have heard.

BUNGALOW

I have no memory of the ghost that haunts this house, although it has defined my entire life.

I was born on a snowy Saturday in the winter of 1962, in a peaceful country where one is free to have every hope imaginable.

But twenty years earlier, in a Europe gripped by the ever-tightening Nazi vise, and in a country forced to choose between national socialism and communism, my grandfather took the brave decision to leave.

Before the Iron Curtain could fall upon what would thereafter become Eastern Europe, he dragged his wife and their three surviving children on a journey that, he hoped, would ultimately lead them to a better future.

I imagine it was then that my own fate began to take form.

For my grandfather, who was born in Transylvania, the Trianon Treaty was nonsense. He did not consider himself Romanian, and had thus exiled himself into what remained of Hungary after the Second World War. It was there he had met my grandmother and started a family.

But when the war began again and new alliances formed, the hopes of regaining that lost territory were revived in the hearts of all the expatriates created by Trianon.

So it was that when northern Transylvania was once again briefly annexed to Hungary, my grandfather chose to bring his family home to the land of his ancestors. Obviously, he was picturing that, come the end of the war, things would return to the way they had been in his memories.

It goes without saying that things rarely happen the way they are planned. In 1944, Romania did an about-turn and declared war on Hungary. Trapped between the Axis and the Allies, my grandfather and his family suddenly became persona non grata.

Days were punctuated by sirens announcing the impending arrival of bomber aircraft, in the chokehold of unsustainable inflation and a dead-end future. It was once again time to escape, but to where? Europe was sinking further and further into a war that seemed to have no resolution and no end.

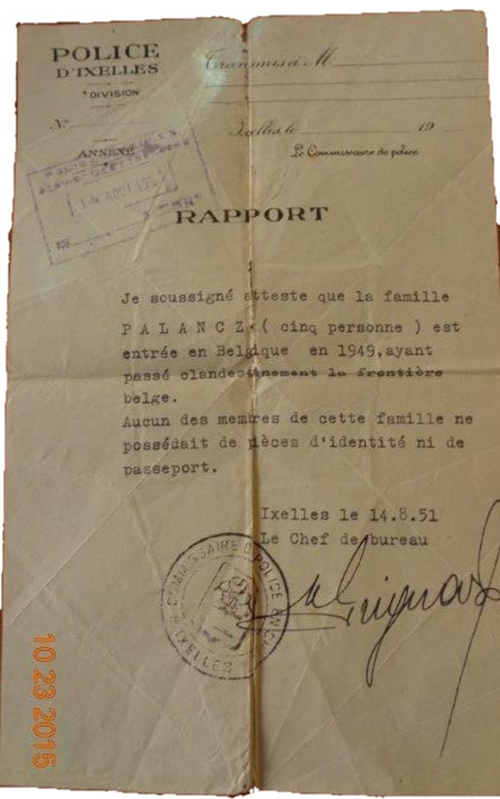

Nevertheless, the need to live came first. They went west with the means they had, though they had papers that weren’t valid, currency they could not exchange and a Finno-Ugric language strangers did not understand.

Refugees at the time were not taken in by a plethora of organizations. There were no camps to house them.

Abandoned barns were their shelter. Food was often donated by good Samaritans who would leave them bread and other goods by sheer chance.

For clothes, they would loot soldiers and other poor souls dead by the roadside.

Antisemitism and suspicion were common fare. Their survival instinct, their resourcefulness and luck were essential to stay alive.

Emotional scars would come later. In those days, all their energy was focused on more important things.

László, 19, was the eldest of the children. He was the only boy. All hopes rested upon him. He considered himself responsible for his parents and his young sisters.

It was a heavy burden for a young man of rather short size and average build. Borne by the impetuousness of his youth, he felt invested with the mission and the obligation to continually do more to help his family.

His bravery eventually got him in trouble. He was separated from his family.

They would reunite only four long years later, quite by chance, on the other side of Europe. Needless to say he was immediately welcomed as the prodigal son.

After that, nothing was ever impossible again.

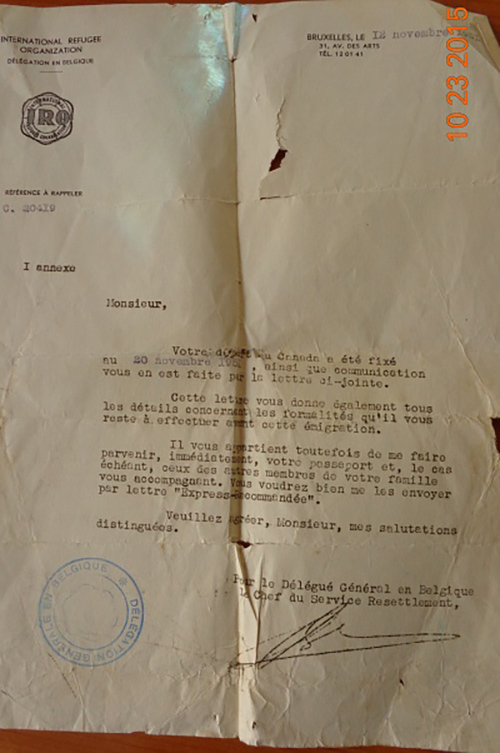

The adventure that would eventually lead my future family to Canada lasted nearly 10 years. It took them through Austria, Belgium and France. Ten years of displacement and turmoil during which all methods were valid to survive, to make life easier to endure, to educate themselves. After all, the siblings were still young, resilient and they still believed in life.

The war eventually ended. Europe began to rebuild, but was now split in two. Their beloved homeland had lost its freedom. Returning home was unimaginable. They were therefore stateless, and they needed to find a future elsewhere. But what land could possibly welcome them?

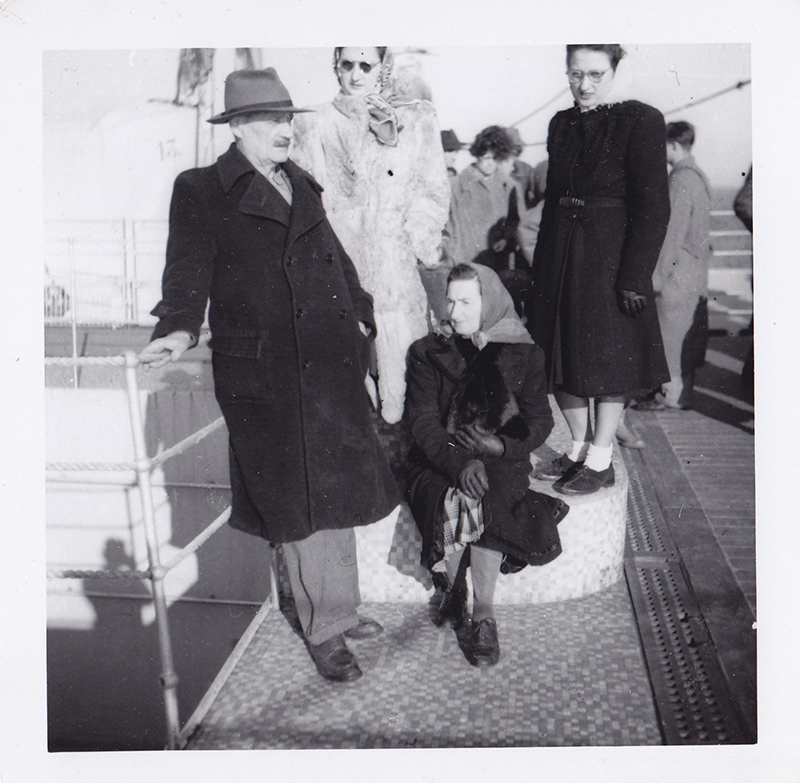

After the war, many countries including Canada considered Hungarians "foreign enemies". It was only in November 1951, with two weeks of notice, my future family received passes to travel to America. That was how, following some ten days of stormy seas, they arrived at Pier 21 in Halifax, on a cold early-December day.

No camera captured the moment. No welcoming committee awaited them with a plethora of gifts. All they faced then was the unknown. Like all immigrants at the time, they rolled up their sleeves and began to build a new existence, even though, contrary to what they had been told, and like today, their degrees were not recognized.

Bit by bit, through hard work and cumulative small jobs, they rebuilt their lives. For people who have been uprooted, the ultimate goal is to once again anchor themselves somewhere.

To achieve this, even combining all their resources, using up all their savings and mortgaging their future for decades was a no-brainer. A bungalow in one of America’s nascent suburbs was the perfect incarnation of their dream. Half of the houses on the block that was being built would belong to immigrants. Many were multi-generational dwellings long before this was a fashionable thing to do.

Swiftly, and despite their relative lack of privacy, the inhabitants managed to breathe life into this house, turning it into a home. Rétes, dobos torta, zserbó, my grandmother would sing while baking delicious pastries that smelled amazing.

My grandfather would tinker in his brand new garage. My aunt would flirt with her many admirers. My future mother would spend her free time skiing or swimming. László’s accordion would fill festive evenings with music. Although they all worked hard to pay their bills and reach the American dream, the future was promising and bright.

Life had triumphed. Weddings and baptisms were the only missing pieces, and they would no doubt come soon.

That is where the story could have, indeed, ought to have ended. But that is not the life I knew.

One morning in August 1963, the accordion fell silent. With it, all the joy and delight that had been rekindled once again vanished. In the middle of a fragile new life, fate had managed to make everything crumble to pieces. Absurdly, it took László just as he was starting anew, and took all of his parents’ hopes in one fell swoop. My grandmother never sang again. My grandfather locked himself up in his memories. My aunt developed multiple sclerosis, and my mother, crippled with guilt, gave up on her dreams and began to care for them all.

I was too young to understand, but as a child I still absorbed everything. Post-traumatic stress disorder was an unknown expression at the time, but I never stopped witnessing its consequences.

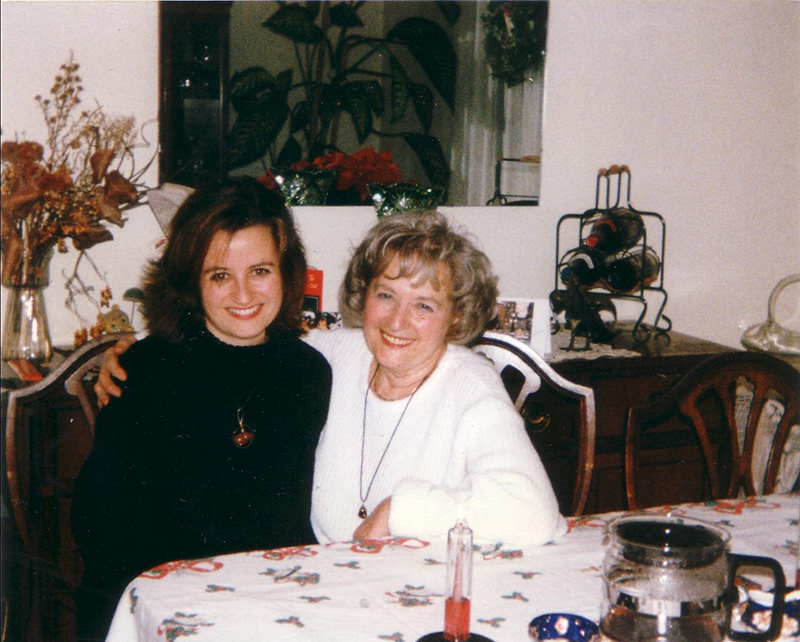

Nowadays, this cute bungalow from the 1960s, the theatre of my childhood and a centrepiece of my life, is but a shadow of what it once was.

Deprived of its inhabitants, its sounds, its familiar objects, it seems sad, cold, somewhat gloomy. Its faded walls and empty rooms echo my steps and fill me with nostalgia. The worn old hardwood floors remind me of happy and unhappy days. Here is where Coquette’s claws marked the floor in her haste to greet us with such enthusiasm. There are the remains of a magnificent Christmas tree that stood tall over the nativity scene and the presents. A walker knocked this hole. That pattern on the tiling was a lake, in my childhood imagination.

Everything is a memory, a whisper of what might have been, what should have been.

I was six months old when László died, so one might well say I never knew him. But every step of my life was coloured by his absence.

What a shame that the living do not get as much adoration as the dead!

I would really have loved to know him, but I hate him for having filled my life with such melancholy.

I have decided not to place this burden on a new generation. None may escape the legacy of their parents, but when one is born of immigrants, the weight of the previous generation is sometimes unbearable. Whether we like it or not, we carry our grief, we are shaped by our suffering, and we cannot escape what we went through.

Tomorrow, a new family of immigrants will move into this old bungalow, bringing their own dreams and hopes. Will their ghosts be less invasive?