Sobey Wall of Honour

Column

181

Row

7

Alumni Type: Immigrant

Country of Origin: Czechoslovakia

Ship Name: T.S.S. Nea Hellas

Port of Entry: Pier 21, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

Date of Arrival: April 23, 1949

Age on Arrival: Alois - 30 years old, Anezka - 24 years old

The following is the story of Alois and Anezka Kolarik’s journey to freedom. It was written by Pauline Williams (Kolarik), their daughter, who collected much of the information from their stories, interviews, historical documents and research. Many details were taken from Alois’s memoirs that he wrote at the age of 92. He started writing his life story on January 20, 2011 and barely put his pen down until he finished on February 27, 2011, some 50 pages later. He knew the clock was ticking. Six months later, Alois passed away.

This is a story of strength, courage, endurance, faith, survivorship, sacrifice and selflessness.

Alois Kolarik was born August 23, 1919 in the little village of Pozlovice, in central Czechoslovakia. His mother’s name was Zofia and his father’s name was Josef. Alois was the youngest of 7 children: Rozalie, Anezka, Joseph, Marie, and Jan. A baby sister Frantiska passed away at the age of two in 1911 and his father Josef passed away in May, 1919 just prior to Alois’s birth.

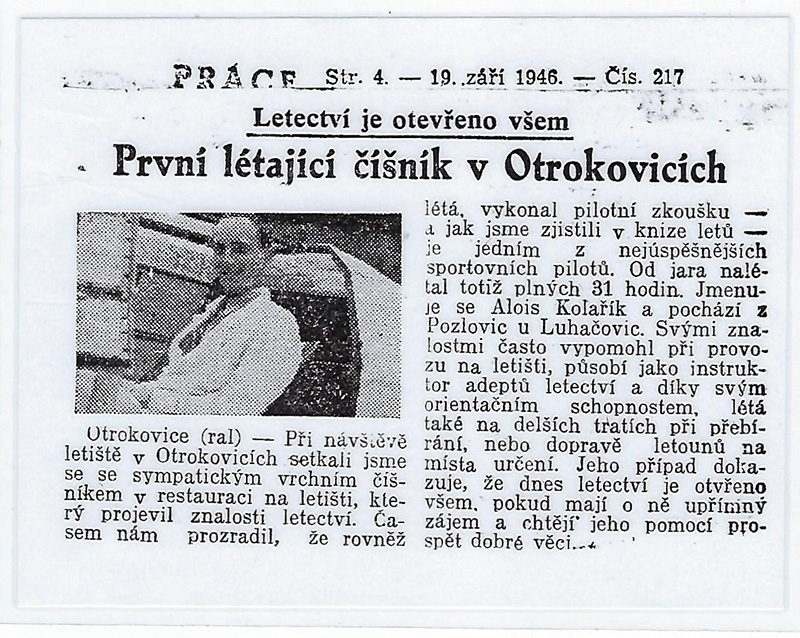

In 1939, at the age of 20, Alois had just finished business school. After much hardship he landed a job with Bata at the Vedouci Restaurant at the Zlin airfield, also known as the Otrokovice airfield. The airfield was built in the mid-1920s by J.A Bata to manufacture aircraft, sailplanes, sports aircraft and to operate an air school. Otrokovice airfield was being occupied by the Germans at about the same time Alois started working there. Pilots and technical engineers were arrested and plane production was limited for use by the German army only.

World War II was breaking out and Hitler’s primary ambition was the conquest of Czechoslovakia. With little resistance, Hitler successfully took control and established the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. The Czech population was mobilized to aid the German war effort. Consumer-goods production was directed toward supplying the German army and the protectorate’s population was subjected to rationing.

The Vedouci Restaurant was a busy place. It accommodated and fed hundreds of workers and German pilots from the airfield and factory.

Alois started as a waiter but quickly climbed to head waiter and by 1946 he was manager. Alois was a hard worker with a voracious work ethic. He was very instrumental with assisting with the development, growth and expansions that took place at Bata during that time.

The Otrokovice Air School also provided Alois the opportunity to learn to fly. He successfully obtained his pilot’s certificates and he became well known for being a sport and tourist pilot. He helped with plane traffic at the airport, flew the tourist planes, instructed and flew long distances to pick up and transport aircraft to their destinations. Alois often bragged about being a ‘bit’ of a daredevil in the skies. On one occasion he flew over the Church of his home village of Pozlovice and threw flowers to his mother – for which she scolded him! Flying under the wires was another acrobatic feat he enthusiastically boasted about. While working at Bata he flew with fellow pilot and close friend Josef Janecek. His Bata flight log book details 233 work related flights.

By 1945 the Germans had surrendered under pressure from the Soviet Union and Western allies, thus ending the war. A cruel twist of fate however soon saw the Russians occupying all of Czechoslovakia and the communists took over the entire country. Communist ideology permeated and dominated every aspect of everyone’s life. Those who did not comply with communism were interrogated, intimidated, put under surveillance and subjected to house searches. Bribes abounded. Alois’s prized Jawa motorcycle was seized, as were most everyone’s possessions, private properties and businesses. The country he said, lost so many intelligent, bright professionals, politicians, business people, professors and teachers. Families were torn apart. He said that communism was the worst poison on earth.

After the war, Alois was told that he must become a member of the communist party if he were to continue working at Bata. After numerous threats, he was arrested and taken away by the military police to the Uherske Hradist Gestapo prison south of Zlin, where he was imprisoned in a small, cold, damp segregated cell.

The Uherske Hradist Gestapo prison was a gathering place for political prisoners prior to being transported to Soviet concentration camps. Alois remembered seeing people one day, then never seeing them again.

After several weeks he had a surprise visit from his good friends Rudolfo and Ludmila Lociga. This couple supplied Alois with meat at the restaurant. They lived in Kvitkovice about one mile from the airport. During the war there was a huge meat shortage in the country and food was rationed; however, because so many German pilots worked and passed through the airport, meat was plentiful - as was coffee, chocolate and alcohol. Alois took risks and saw that his family and friends like Ruda and Ludmila got a few of those treats. Ruda loved coffee! So it was these kind friends who would occasionally bring Alois hot chicken soup while he was imprisoned. After six months of waiting with nothing happening, Ruda and Ludmila hired a lawyer from Uh Hradisti. With the help of the lawyer, the judge cleared Alois of any wrongdoing and he was released. Alois was forever grateful to Ruda and Lulmila and he never forgot them.

After his release, Alois could not return to Bata because his position had been filled by a communist. So Alois went to live with his brother Jan and his wife Anna in Zlin, and his other brother Franta was successful in getting him a job as head waiter at the Sokolovna restaurant.

By now, Alois knew that Czechoslovakia was not the place for him. He knew he would be arrested again so he contacted his close friend Josef Janecek and together they planned their escape. Sadly, their plan failed when another pilot friend from Malenovice backed out because he did not want to risk stealing a small plane for their escape.

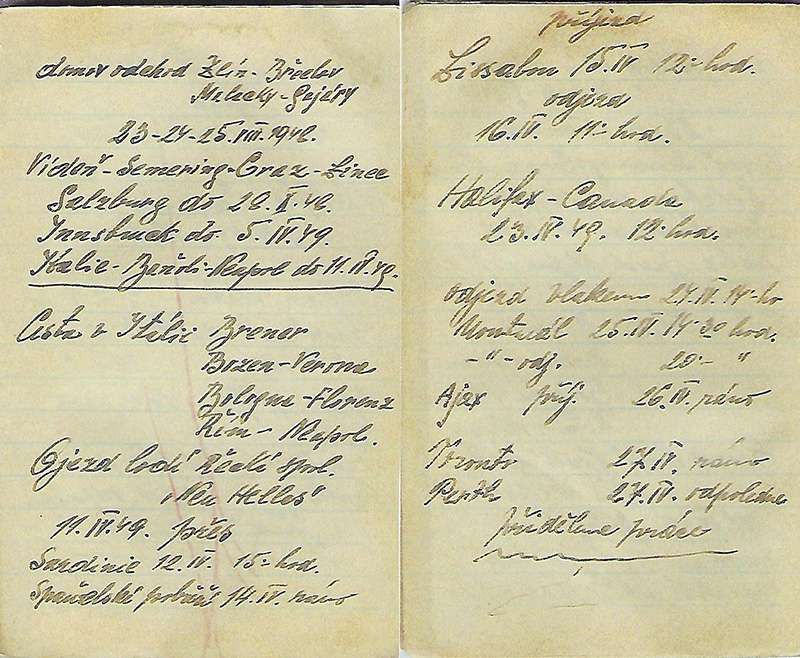

Their next plan was to contact someone in the underground movement. They found someone in Zlin who would help them escape for 42,000 Czech Koruna each. They both agreed and the escape date was set for August 23, 1948. Ironically this would be on Alois’s 29th birthday. At five o’clock early that morning Alois’s brother Franta came to say good bye and brought him a warm sweater. He was the only family member who had a clue about their plan. It was risky to tell family members or friends as it would put them at extreme risk.

Josef and Alois traveled from Zlin by train to Otrokovice, then to Kvitkovice so Alois could say goodbye to Ruda and Ludmila. The pair returned to the train station in Otrokovice, then traveled to the closest station near the Austrian border where they spent the night. The next day they were to meet a man who they were told would have a long handkerchief hanging out of his coat pocket. The man drove them to a wooded area near the border. He left them in the blackfly infested forest, saying he would return later that afternoon. True to his word, the man came back and together they trudged through the bushes and forest for about half a mile until they reached a potato field that ran beside the river. Between the potato field and the river Russian soldiers were patrolling back and forth carrying guns with bayonets. The men crawled on their bellies to where the soldiers were patrolling and once the soldiers passed, they waded into the Danube River where it touched the border of Austria and Slovakia. It never occurred to Alois that he would need to swim in order to escape and guess what – he could not swim. He was terrified but there was no turning back. He put his small leather suitcase on his shoulder, felt for his crucifix that was close to his heart and he prayed. Alois said it was a miracle he did not drown and forever thanked God and the few slippery rocks on the river bottom that helped get him to the other side.

Exhausted, the two were taken to a nearby house and the man who helped them disappeared soon after. Two ladies (one spoke Czech), gave them breakfast, a place to bathe and washed their clothes. They were now in Austria but still in danger because they were in a Russian zone. Austria was divided into four zones occupied by the United States, Soviet Union, United Kingdom and France.

From here, they traveled by train to Vienna where they asked an English speaking soldier for assistance, only to be laughed at. Not to be discouraged, they found a Catholic Church where the nuns gave them food and helped them contact the American police. They were told to go to Innsbruck where they would be safe in the French zone. The only problem was, they had to travel through two Russian check points to get there. To make things worse, the American police asked them to take a 19 year old Slovak soldier by the name of Milik with them because he was traveling alone. Sadly, Milik changed his mind at the last minute and wanted to return to Bratislava to find his girlfriend. The next day Josef and Alois heard that Milik was shot by Russian soldiers on the bridge in Vienna.

Eventually Alois and Josef made it to the train and were on their way. At the first check point the Austrian conductor covered for them and told the Russian soldiers that their papers were in order. At the second check point Alois and Josef were sitting across from each other so they put their heads down on the table in front of them and pretended to be sleeping. Again they were spared and not questioned. If the Russians had intercepted they would have all gone straight to Siberia – or worse.

The next morning they arrived in Innsbruck. It was their first step to freedom but now they needed a place to stay. With luck on their side, they met Rudolf Mohry, a political figure and deputy mayor of Brno who had also escaped. Rudolf had connections with the Swiss Social Democrat party who provided shelter for all of them at the Innsbruck Salurner Strasse. Here they were safe until their papers were processed to immigrate abroad.

A few days later Alois was walking the main street in Innsbruck and looking ahead he saw a young lady standing and staring into a store window. He had a feeling she was not German or Austrian, so he approached her. To his surprise, she responded in Czech! Overwhelmed with emotion they both stood there crying and holding on to each other. Anezka Kanova Buranova was lost, tired, hungry, and alone with nowhere to go or to sleep.

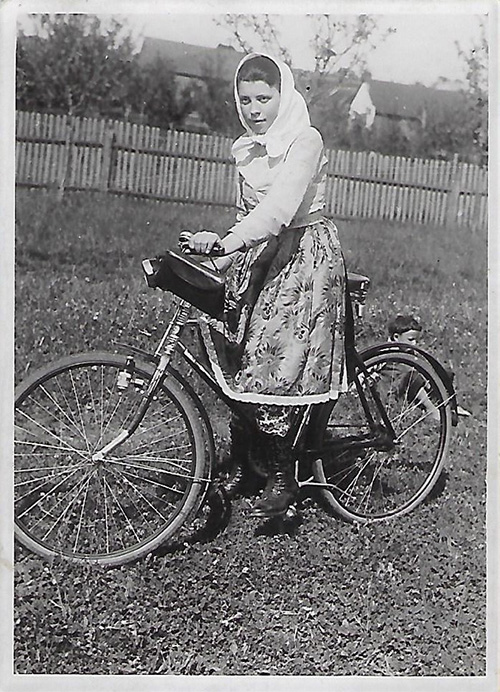

By way of introduction, Anezka Buranova was born January 15, 1925 in Havrice Uhersky Brod Czechoslovakia. Her mother’s name was Anezka and her father’s name was Simon. She had two sisters, Marie and Hela and two brothers, Paul and Jarek.

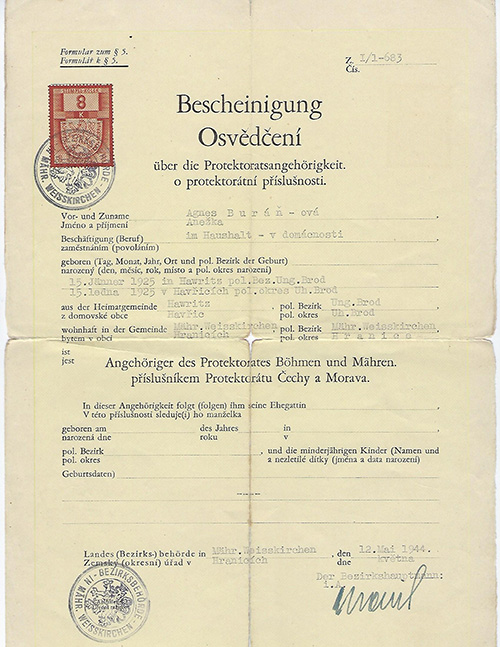

When WWII started in 1939 Anezka was sent to the Ludmila Sisters of the Holy Cross Girls School in Napajedlich. She was only 14 years old but needed to go there because it was the safest place for her to be. She remembered having to darken the windows with blankets. Blackouts were the norm, so was rationing. She was given new identification and was forced by the Nazis to sign protectorate papers. Anezka became part of the protectorate population that the Nazis wanted to Germanize. People were trapped and could not go anywhere without a visa. School books were burned and replaced with pro-Nazi textbooks. Democratic rights and freedoms were violated, radio and newspapers censored, and human atrocities committed including the deportation of Jews to concentration camps. Many people were executed and many chose suicide as a way out.

During her schooling years spent with the nuns Anezka also learned to cook and bake. They say there is a reason for everything and as it turns out Anezka had a natural talent for baking and decorating the most beautiful cakes and pastries in the world!

By 1942 and at the age of 17 Anezka went back home to live in Havrice, in the south Moravian region.

It was a time of war and turmoil. For the protectorate population, German occupation represented a period of oppression. Human loss from political persecution and deaths in concentration camps totaled over 50,000. Over 75,000 Jews were murdered.

This was the year that Nazis had massacred the entire village of Lidice – and other towns in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. All males over the age of 15 were shot, the women placed in concentration camps and children sent away to institutions. Pets and beasts were slaughtered and human remains were unearthed and looted for gold teeth and dental fillings. So many atrocities were taking place. The Nazis took away the Reich citizenships of German women who married non-Germans and Czech women who married German men were accepted into the German Volk (nationality). Czech families strongly encouraged their daughters to marry German men in order to save their family businesses.

Sometime during this timeframe Anezka married a German officer. They had a baby named Helen but the marriage was short lived. Sadly, they divorced and he left the country.

It was 1947 and Anezka at the age of 22 was working as an administrative officer in Chvalovice, a small village that sits on the border of Austria in the south of Moravia. Anezka was working on the local national committee that administered jurisdiction over municipalities and dealt with post war issues.

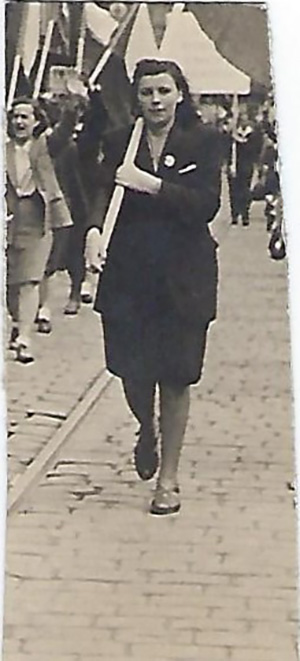

Anezka was being watched closely because of her membership in the Czech National Socialist Party. The Nazis formally suppressed and persecuted those members. Under German occupation, the Czechoslovak National Socialist Party functioned in exile and most of its members were active in the resistance movement. Anezka was a prime target and she knew it. She was an outspoken, strong woman whose beliefs fueled her desire to escape from her terrible life. She hated the communists with a passion.

After Czechoslovakia became a communist state in 1948 Anezka was severely pressured to join the communist party. She was threatened repeatedly. Her family lost their large sugar beet farm in Havrice putting many people out of work. The family business, their private property and all their possessions were seized.

So it happened one day towards the end of November 1948 the military police came to Anezka’s apartment to arrest her. Anezka was not one to bow easily to anyone’s demands so she convinced her aggressors that she needed to get a sweater because it was cold outside. Indeed it was cold! She ran upstairs and in a state of panic, otherwise known as ‘fight-or-flight response’, she did what she had to do! Anezka opened the small bathroom window of her apartment, climbed out on the roof and jumped to the garden below. With all the adrenaline she could muster, she fled to the building next door which happened to be the offices of the border guard. She knew most of the security guards who worked there. Within minutes she was sitting on the back of one of the officer’s motorcycles being driven across the border into Austria. It happened that fast! The guard’s uniform did not arouse suspicion. It was a spontaneous, courageous and very dangerous escape. Once Anezka was safely across the border she contacted her colleagues from the underground network associated with the Czech Resistance Movement. Her friends helped get her to Salzburg and then to Innsbruck. Once she got to Innsbruck she found herself wandering the streets alone, staring into a ladies dress shop, hungry and tired.

It was at this very moment that a stranger by the name of Alois Kolarik approached her. After an emotional chance encounter, with both of them crying, Alois took her with him and asked Rudolf if she could stay at the Salurner Strasse. Rudolf agreed, so all together there were seven men staying in one large room and three women living together in a smaller room. They had all escaped, they were alive and were lucky to be together in a safe place. With the help and support from the International Refugee Program and the Red Cross, they were now in a position to immigrate to one of the many countries who opened their doors to them.

Anezka made contact with her sister Marie and she knew her baby Helen was being cared for by family. She longed to be with her child and knew it was not possible, but hoped they would be reunited one day. For the young mother who had just escaped, little did she know that it was not meant to be. The real Iron Curtain had not yet been created and the totalitarian rule would last over 40 years. By the time the Iron Curtain was lifted Helen would be a grown woman, educated and married with a child. It will go down in history that this period of time transformed the lives of many people and families. Family trees were changed forever.

For Anezka it was dangerous to communicate with anyone during this time. A person known to help someone escape could face arrest or a possible death sentence. Anezka lived through this turmoil and spoke very little about it. Many painful memories haunted her until the day she died.

During the winter of 1948 Anezka and everyone at the shelter got their immigration papers together. Josef Janecek decided to go to England because Canada was too far away for him. Canada however, was the chosen destination for Alois and Anezka.

On April 5, 1948 Alois and Anezka, along with many others, left Innsbruck by train, and traveled through Brenner Pass Italy, to Bozen, Verone, Bologne, Florence, Rim and finally arrived in Neopol (Naples) Italy.

Alois and Anezka along with the others stayed at the Displaced Persons Camp in Bagnoli which was in the western seaside quarter of Naples. It was run by the International Refugee Organization and it is at this camp where an appalling atrocity was knowingly committed after WWII. About one thousand displaced people were categorized correctly or incorrectly as ex-Soviet citizens and their ultimate fate was execution or imprisonment in the Gulag of Soviet Russia.

On April 14, 1948 Alois and Anezka boarded the Greek Ship T.S.S. Nea Hellas in Neopol. The ship stopped at the ports of Sardine, Italy and Lisbon, Portugal before sailing the rough transatlantic. Anezka was nauseous and sick for most of the journey.

On April 23, 1949 Alois and Anezka along with 833 other passengers, arrived at Pier 21, Halifax, Nova Scotia. Alois was 30 years old and Anezka was just 24.

Imagine the drive and tenacity they had to leave behind their beloved country and family - no language, few possessions, and little money - just a strong yearning to start a new life with freedom and the courage to come to Canada on a Ship of Dreams.

Following the disembarkation process at Pier 21 Alois and Anezka traveled separately - Anezka by bus and Alois by train from Halifax, Nova Scotia to Ontario and to their destinations of Perth and Britannia (Ottawa).

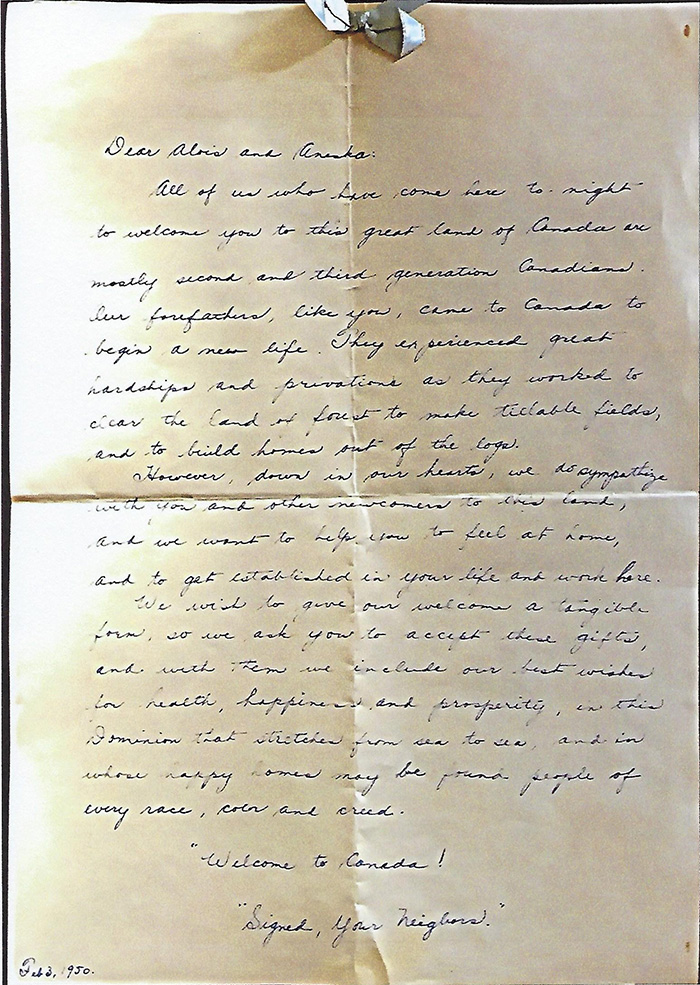

Alois arrived in Perth on April 27th, 1949. He started to work the same day on a farm on the outskirts of town owned by George and Mary Drysdale. Often he would reminisce about the hardships on the farm and shared many fond memories of the neighbors who helped each other and how welcoming they were.

Alois was a quick-study when it came to learning the new language. Grandfather Drysdale would come to the barn and field every day to teach Alois a few new words. Because he learned English pretty fast he was asked to interpret for the unemployment office whenever translation issues arose with other new immigrants. His good relationship at the unemployment office served him well in securing a job after his contract on the farm was finished.

Anezka arrived in Britannia, on April 29, 1949 and began working for a dentist Dr. Cummings and his family. In the meantime Alois immediately started to work hard to bring Anezka to Perth and with the help of the unemployment office she was allowed to relocate to Perth and both were reunited.

Alois and Anezka married on November 26, 1949, settled in Perth and very soon had three daughters, Lili, Pauline and Lois. They were blessed with one cherished granddaughter Sandra and two beautiful great-grandsons Kolton and Weston.

Alois and Anezka were hard working and well respected. They loved their hometown Perth very much. Their family, their home and Canada meant everything to them. Alois enjoyed a happy and successful 41 year career with Perkin’s Motors. He managed the Bowling Lanes for many years and then rose to become one of the top national salespeople for General Motors Canada.

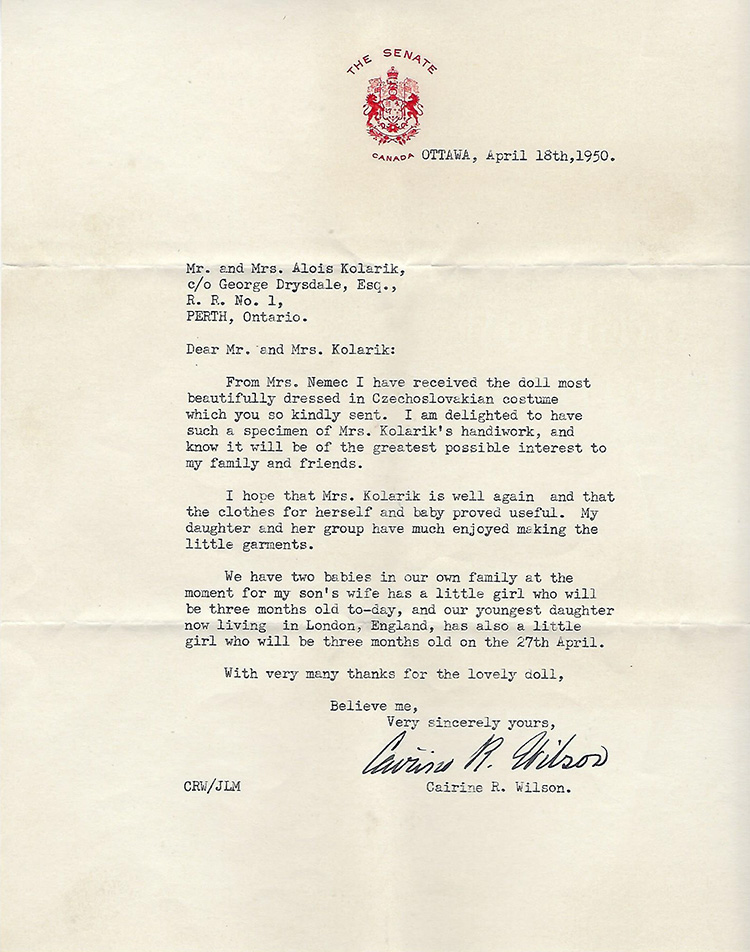

Agnes started her own baking and catering business. She was known far and wide for her extravagant tortes; wedding, anniversary and birthday cakes; fancy sandwiches; petit fours; Christmas baking and many a lavish spread! Every one of “Mrs. Kolarik’s Cakes” were a one-of-a-kind creation. Her talents were extraordinary and her memory lives on in many families and generations because of her amazing works of art.

All three daughters and granddaughter became members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). Pauline’s husband Greg was the first ‘Mountie’ to come into the family, followed by Lili, then Lois. Pauline and her daughter Sandra were Registered Nurses before joining the RCMP - Sandra as a uniformed police officer and Pauline as a proud Civilian Member.

Al and Agnes were married 58 years and were devoted to each other until the end. Agnes passed away on November 11, 2007 and Al joined her on September 14, 2011. Great Grandpa ‘Al’ lived long enough to meet and give his blessings to his first Great Grandson Kolton who was named after the ‘Kolarik’ surname. That day and that union is a story in itself! Alois knew his time was running out and meeting Kolton was a must-do before joining his beloved Anezka.

Their legacy was their family and a desire to make a better life for them. Their unending courage, bravery, sacrifice and pain was not in vain. Thank you Anezka and Alois, ‘Mom and Dad’ for everything. Mostly for the opportunity to live, work, serve and contribute to making Canada the best country in the world.

Thank you Canada for welcoming these two brave people and for helping them plant a new family tree on Canadian soil.