Sobey Wall of Honour

Column

78

Row

2

"There are things of which I may not speak, There are dreams that cannot die; There are thoughts that make the strong heart weak, And bring a pallor into the cheek, And a mist before the eye."

These words from Longfellow's poem "My Lost Youth" have perhaps more meaning for me than for most people, although it may be in a different way from the meaning the poet had when he wrote the poem. To me those words mean that I have seen and experienced so much during my childhood in Danzig; that the things are hard to speak of, because they have been so horrible; but the memory cannot die, and yet, it makes me sad to think of them. And even in such a country, a country of tyranny, barbarism and hatred, people have dreams of freedom and liberty, which, may come true to some of them but may not come to others. We had our dreams come true. Like a sunbeam from a clouded sky, came a permission for us to come to Canada, a free country.

Things had been going from bad to worse for the people who were against the Nazis. Here, where everybody is free, one does not realize, just how terrible it is to be ruled by a dictator. Danzig was called a free city, but it was under the authority of both Germany and Poland, although some things were controlled by Danzig itself. However, the majority of the population of Danzig was German and thus, Hitler thought he could dare to control more of Danzig than he should. We lived in a summer resort, about fifteen minutes from Danzig city. The street car could take us to Danzig and its vicinity. The population of our little town, Broesen, was about 4,000 people. Everybody in the place liked us. There was only one church in the town, and though we were not members of it, we were invited to every special service or party which the members held. My parents were members of the I.O.O.F. for fifteen years. At Christmas the I.O.O.F. gave a party for poor children, and each of the members gave an outfit to a child. However, when Hitler became the ruler of Germany in 1933, he forbade the Odd Fellows to have any more meetings. Not only did my parents give generously to the I.O.O.F. but they also did many things for other poor and sick people, and thus, the Nazis of our town were afraid to treat us badly. Aside from that, ninety per cent of the people of Broesen were Catholics and most of these were anti-Nazis also, and would have rebelled if any of the people would have hurt us or them.

As the Nazis of our town would not do anything to us, and also the other people who were against Hitler, the Government sent Nazis from other towns to annoy us. These men came at night, broke the doors and windows of some of the people's houses, and brought the head of the family to a place which was unknown to all other people. The next day, the family of such persons would get a little gift. This gift consisted of a dainty, little parcel, mostly a box, wrapped in tissue paper and tied with a brightly colored ribbon. When it was opened, one found in the box the remains or ashes of the person of the family which had disappeared the night before. Also a little card was enclosed, a card of sympathy. When children start to go to school they do not belong to their parents any longer, they belong to Hitler. Instead of going to bed at night, they have to go to their meeting and exercise half of the night. The boys are also given a dagger with which they are allowed to kill whomever they wish to kill, except a Nazi, and when they have killed an innocent old man, or even their own parents because they have said something against Hitler, the boys are even given a medal for bravery from their leader. Often, parents came to us at night, because they were afraid in the daytime, as they might be watched. When they came they used to complain of the Nazis. Of course, we could not help them, but it made them feel better to talk to someone who understood. The Government even threatened the principal of our school because he let us go to his school. We had to leave and go to private schools. The minister of the Church in our town, found on his doorstep two halves of a cat on a gallows, accompanied by a note which said: "Today the cat, tomorrow you." Also, the same minister found his chicken-house robbed, but a note saying "God is everywhere, but not in the minister's chicken-house" was posted on the wall. In that way they wanted to show that, although the minister talks about God, there is no God because otherwise he would have protected the Minister's chickens. But people knew that there is a God, and no thieves could make the people of Broesen believe that there is none.

My aunt had a store in Danzig city. My uncle was a teacher at the College, later on, he had his own school. One day, when he passed by my aunt's store, he noticed a big crowd standing there. Then, when he looked a little closer, he saw a man with a can of paint and a brush writing on the windows, "Do not buy anything here, for these people are against the Nazis." My uncle became very angry, and when the Nazis picked up the can to put the brush in, my uncle gave the bottom of the can a push and all the paint went into the Nazi's face. Some of the people laughed, others cried "kill him" but there were not few who even cheered. My aunt was frightened, and quickly pulled my uncle into the store. When my uncle came home, he found in his study a basket with flowers and a note which read: "You have done something very splendid and I send you this as an appreciation." My uncle did not have any trouble because of the thing he did. He believes that the Nazi who painted on the window was an old pupil of his, and so was afraid to go to the police.

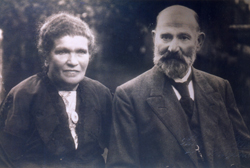

My grandfather lived in a town in East Prussia. When we knew that we were going to Canada we, that is my father, my mother and I, went to my grandfather's by bus to say good-bye to them. Our journey was quite pleasant until we came to the Danzig border. There, an officer looked at our passports and asked if we had much money with us. As we were going to my grandfather's, we did not need any money and so we could truthfully say that we hadn't any. But, because we were the only people in the bus who did not wear a swastika, the officer thought we were anti-Nazis. My father was the only one who had to leave the bus and the officer took him into a very small room. There he said to another officer: "Now we've got one." My father said: "perhaps you think that everyone who does not wear a swastika is a criminal!" The officer replied, "We'll see." The room into which my father was brought was so small that he could not even move his hand so he could take his handkerchief to blow his nose. He had to stand with his arms above his head while the officers looked into all his pockets and other places, but, of course, could not find anything. Now we thought everything was over and we could finish our journey in peace, but we were greatly mistaken. We now crossed the Nougat River and with that we entered into Germany. We were noticed again, mainly, because we had no swastika, but also because the Danzig officer had telephoned to the German officer and had told him to annoy us. Here, we all had to go out of the bus. They looked at all our things, and as we had some sandwiches with us, they opened them, took off the meat and the other things which were on the sandwiches, scratched off the butter and looked through the bread with the help of a flashlight. Next, they found my autograph book. They asked us why we have it with us, and my father said that we were to go to another country and that I wanted my relatives autographs before we leave. When the officer opened the book, he saw the following, which was written by my mother: "if a poor man begs of you, give him something; if someone is sick, comfort him; if someone has died, put him into his grave; do not ask what his rank and religion are, he is a man like you." The officer looked at us; then he closed the book and threw it at us. He did not say anything. Probably he saw by the verse how a person should act. However, a second officer came and took my mother to a woman who had to undress her completely, and looked at all her things to see if she had anything with her which she was not allowed to have. They cut my mother's girdle into pieces, ripped the hem and seams of her dress and cut the soles off her shoes; but they were polite enough to paste the soles on again. In another room they did the same thing to my father. Strange to say, they did not touch me at all. The bus was two hours late on account of the interruption. The other people in the bus were angry and said that they, who had butter and eggs and many other things, were not examined, and we who did not have anything were being inspected for two hours or more.

The bus stopped at the principal station and there were some of our relatives to meet us. We all went into the waiting room because they wanted to tell us about the things which had happened in the city, so that we would not be too surprised when we saw them. After that we drove to the graveyard in which several of our relatives were buried. The graveyard had been new and was very beautifully kept and had a church which had been of the most beautiful modern style. But we did not see that anymore, all we saw was a pile of bricks, and mortar, and glass. The Nazis had burned the church and had ruined all the graves. The grave of my grandmother had a new stone which covered the whole grave, and this was the only one which was still there. The graveyard had also a gardener who kept the graves in order and was paid by the people. The Nazis had taken that man to the concentration camp for doing absolutely nothing and had just been set free the day when we visited the graveyard. As we passed through the streets of the city, we noticed that one synagogue was also burned down. This had been a building which was a synagogue on one side and an orphanage on the other. One night the Nazis came and burned it down, throwing the orphans in their nightgowns through the windows. Kind-hearted people who picked the children up and took them home with them were sent to concentration camps. We had seen enough and so we wanted to go home, to our grandfather's place. However, that wasn't any better. My grandfather, who was then eighty-one years old, owned his house. One day in November, at six o'clock in the morning, the Nazis had come to the house. They had broken all windows -- there were fifty-seven windows -- and had also broken all furniture, so that they had to use it for kindling later. Only a few very necessary things were left. They also broke my grandmother's china and cut glass. One of the Nazis did not like doing it and so he threw the things into the beds where it was soft and could not break. After the Nazis had finished, they told my grandfather that in six hours he must have all the windows fixed and must also have cleared the place as the Government was going to put a Nazi family into the house. My aunt begged them to let my grandfather stay as he was an old man and would not know where to go. So the Nazis changed it around a bit! They told my grandfather, that, while they were ruining his house, other Nazis were doing the same thing at my uncle's, who lived just around the corner. They said, that, if my uncle could live with my grandfather so that they can put a Nazi into my uncle's house, it would be all right. My grandfather said, of course, that he would do it. Where my uncle had lived until then, the house was rented. My uncle had paid rent for six months in advance and the Nazi owner had asked if the government would not let my uncle stay those six months but he was told to be quiet or they would put him into a concentration camp. We had seen enough and soon left again. On the way back, we did not have any trouble in the bus. The officers recognized us and knew that we spoke the truth. Before all that happened, people in Danzig lived very peacefully. We, ourselves, had a very nice home and beautiful garden. In the summer our friends and relatives from the city visited us every day, and we all went to the beach which was only a little way from our house. We used to take our lunch with us and stayed till evening or we went walking in the park. Later on, when Hitlerism was more advanced, Jews and anti- Nazis were not allowed in the park and on most places on the beach.

When things became too unbearable, we decided to leave the country, and we were very fortunate in getting a permission to come to Canada. We sold most of our things, but many we packed and sent to Gdynia, Poland, from where we sailed to England. We left Danzig in February 1939 and stayed in Gdynia for ten days before we sailed away. Many of our friends came to see us in Gdynia and many of our old friends in Broesen told us not to leave. One woman, whom we met on the street in Danzig just before we left, said loudly: "All the good people leave and the bad ones stay." Everybody brought us souvenirs and other things but we had too many and had to leave most of them. It was hard to leave our friends, but it was impossible to stay, on account of the Nazis. Everyone asked us to take them with us, but that too was impossible. On February 16th, 1939, we sailed to England on the Polish liner "Luvow." There we stayed four days and then we boarded the steamship "Andania" and sailed to Halifax. In Halifax we were welcomed by a lady who brought us to a hotel where we stayed eight weeks. We were constantly looking for a farm with the help of some very nice people who have become our very good friends. We bought the farm on which we live now and are much happier here then we were in Danzig. Of course, we work hard, but we have our freedom and that is better than living in a country of slavery. We do not wish to go back to Danzig because we like Canada very much. It is a land where all people have equal rights, where everybody may worship in his own way and where all people are free. May it always be so, and may no dictator ever have a chance to set foot on Canadian soil.

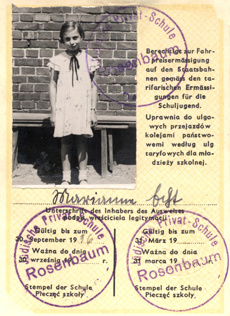

Marianne Echt. Age 16 - 1942

We arrived at Pier 21 on a snowy, stormy day, March 7th, 1939, from the former corridor between Germany and Poland, Danzig. My father, having come from East Prussia to Danzig, had a German passport and we children were all listed on that. We spoke German and were escaping from the old country to a country where people did not have to be afraid to walk on the street. I was 13 years old and with me were my parents, my maternal grandmother and my two younger sisters. We were met by Mrs. Sadie Fineberg, who was so welcoming and friendly and who introduced us to a number of other very kind people, that my parents decided we would remain in Nova Scotia instead of going into the Montreal area, as was originally intended. We had to come as farmers, although my father was actually a pharmacist.

At that time, Pier 21 was a rather dismal and dingy place, but the welcome was sincere and we did not even think of Pier 21's appearance.

After WWII, when Sadie Fineberg became the representative of the Mayor at Pier 21, my mother took over Mrs. Fineberg's job of greeting the immigrants on behalf of the Jewish Immigrant Aid Society. Mother often had many, many holocaust survivors coming in and asked me to come and help her. It was then that I became once more aware of Pier 21 and, having been treated so well when we arrived, we did the same for the people who came over, many of whom were very pitiful human beings.

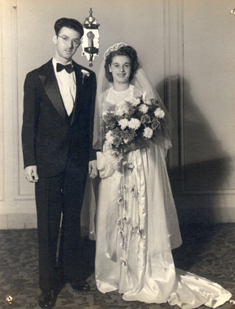

On October 20th, 1946, I married Lawrence Ferguson (a nephew of Sadie Fineberg). We have 3 children, Randy, Lea and Jamie and 4 grandchildren, Simon, Matthew, Rebecca (Becky) and MacKenzie.

Many years later, Mr. J.P. LeBlanc and Trudy Mitic were writing the book Pier 21 and I was called to be interviewed. When they had the launching for the book, we were invited and it took place at Pier 21. Going there brought back many memories of my mother and myself meeting refugees, and I became very nostalgic. I told Mr. LeBlanc that I would be interested to join in anything they were doing in regard to the Pier and later on also when Ruth Goldbloom took over. There was an exhibition at Mount St. Vincent which we attended and there was a speaker and Mr. LeBlanc asked me if I would say Thank You to the speaker on behalf of all those who attended. One thing led to another and I was called for a get-together at the office on Brunswick St. and later on, just before the new Pier 21 opened, also received a call to see if I would come to help pricing items for the gift shop and unpacking boxes. I even took my son, Randy, and one of my grandsons, Matthew, who was on vacation from school, with me and he helped with the packing, unpacking and the setting up of the gift shop. By that time, people had come to my home to interview me and I was also asked to stop in at the CBC TV for some pictures and interviews and a photographer from Reader`s Digest came to take pictures of my husband and me and two of our grandsons, walking by the water at Pier 21.

When Pier 21 was about to open in July 1999, I was photographed by the CBC while helping in the gift shop and this was shown on television. A very pleasant thing happened after that, I received several phone calls and letters from people I had not seen in years, even former students who went to school with me in Milford over 50 years ago. Some of them have visited me and Lawrence and I visited a friend in Dartmouth. I am expecting another friend who now lives in Kitchener, Ontario, and she is coming over to visit me. During my working life, I was a medical secretary and worked for a long time at the IWK, even when it was still the old Children`s Hospital , the VG and Infirmary and later also the Grace. I do not consider myself a very talented person, but I have a number of hobbies, reading, theatre , music, knitting, embroidering, canasta, bridge, volunteering, walking, swimming, traveling, baking, cooking and shopping.

My computer skills are reasonably good and I use them to type various things in the Pier 21 Resource Centre. I have done some fund raising, have been president of several organizations and have sat on the Board of Shaar Shalom Synagogue for many years. In November, I received an award from the Atlantic Jewish Council at their bi-annual convention in Moncton, for my many years of doing community work for the Jewish community as well as the general community. I do not have First Aid training, but have worked for doctors and in hospitals for many, many years and have learned to recognize various signs and symptoms. When a gentleman was coming out of the theatre last summer, I noticed that it seemed difficult for him to breathe and he said that he had a bad heart and was having chest pains.

I asked him and his daughter to sit down and went to the desk where we called 911. They arrived promptly but the man was feeling better and did not want to go to the hospital. However, he was examined by the paramedics and I felt that we did the right thing by calling 911. He could have had a severe heart attack and even died at Pier 21.

I have done quite a bit of public speaking, although I don't consider myself a great speaker. I speak German fluently and have given tours in German for people who have requested it.

My daughter, Lea McKnight, occasionally also volunteers at the Pier. She cannot do it on a regular basis as she is a counselor at a large high school and is extremely busy, but will come if she is needed or during her vacation.

While volunteering at the Pier, I sometimes used to bring my granddaughter, Becky Ferguson, to help and she liked it very much. She was only 13 or 14 years old then, but she became so interested in the Pier that this year, 2003, she applied for a summer student job and was accepted. She is looking forward very much to work at Pier 21. So that's how it goes, from generation to generation, and that is how it should be. Children should be interested in their heritage and should know how things used to be.

Pier 21 is one of my favorite places and I look forward to coming every week, at least once, and if needed, more often.

Marianne Ferguson 2003