Sobey Wall of Honour

Column

22

Row

25

The War-time Experiences of Iris May Cunneyworth (nee Stovell)

A War Bride Remembers

Iris Cunneyworth was born to Charles and Daisy Stovell in Bedfordshire, England on May 6, 1921. She entered the world in her parents bedroom in 'The Horseshoes', a pub dating from the 1800's in the little village of Wrestlingworth. Her birth was followed by a brother Hedley and a sister Olive. In 1944, she married Bob Cunneyworth, an Airman with the Royal Canadian Air Force. In doing so, she set the wheels in motion for what would be a challenging sea voyage to Canada in March of 1945 when the North Atlantic was at its worst. Thus, she became one of Canada's 50,000 War Brides to make the long journey to join with her husband in this new faraway land. It would be 22 years before she would re-unite with her parents and siblings on British soil.

This is her story:

When WWII broke out in 1939, I was 18. Each night my family and I would spend many hours glued to the radio listening to the BBC as WWII began. In our little town of Wrestlingworth in Bedfordshire, uniformed Military troops quickly became a common sight adding to our own auxiliary troops (Territorials) who had been holding war exercises for the past year.

In those early days of the war, I was a member of a social club that volunteered to run a canteen and this turned out to be a good means of meeting different people. My father worked for the ARP (air raid precautions) and had a little office in our local village hall where the social club was also located. At the age of eighteen, he kept a keen eye on me. Like everyone, our family could hear and see the air raids taking place in London night after night. The burning fires from the bombing were visible for miles.

With the start of the war, I was conscripted to work in a government training centre using a large grinding machine. Here I was placed on shift work and lived in a dormitory similar to that used by the troops. My duties at that time were to fabricate crankshafts for trucks. Although I learned to use such tools as a micrometer, I suspect some of these trucks may have had difficulties later on! The crankshaft milling machine used a fluid that turned out to be poisonous to me and after getting a serious infection in my arm, a doctor told me I shouldn't return to this type of work. Since I was under government conscription orders, I was subsequently assigned to an airplane manufacturing factory where I fabricated altimeters for Naval Air Patrol. Although the aircraft factory was five miles away, I was able to live at home by riding my bicycle to work daily. In those days, I and all my friends rode bicycles everywhere, including to dances. Some of my friends were assigned to work on farms. I also worked on a farm for a short period before being called up by the government.

My sister Olive joined the WRENS but my brother Hedley was still in school. My father did ARP work (air raid precautions) throughout the war while my mother stayed at home and kept 'the home-fires burning'.

My family home in Bedfordshire was encircled by many Canadian, British and American aerodromes. Two in particular were huge American bases. At Tempsford and surrounding villages, my friends and I would attend their dances. I later learned that planes from the Tempsford base were used to transport spies to the continent. It turned out that some of these individuals became notable spies for the allied war effort. (For further details, refer to a book "Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire Airfields in the Second World War" by Graham Smith). Unknown to us at the time, I and my friends were rubbing shoulders with some of these brave individuals. From one of these bases, my sister Olive dated an airman who later became a prisoner of war.

With these aerodromes surrounding our village, we became accustomed to the constant drone of planes taking off and landing. We wondered why some on takeoff didn't sound the same as planes which were obviously labouring with a heavy load of bombs. Bomb laden planes had a distinctive sound as they struggled into the air. I didn't realize at the time that many of these planes were dropping leaflets atransporting spies, something we learned only after the war ended.

I met my husband in 1943 while he was working in the orderly room of the RCAF's 405 (Vancouver) Pathfinder Squadron. His name was Joseph William Robert Cunneyworth, although his parents and friends called him Robert. I always called him Bob.

I met Bob at a dance where just about everyone met in those times. We British girls felt that the Canadians and especially the Americans were not especially good dancers. These foreign troops seemed to shuffle around the dance floor in contrast to the ball room dancing that was so popular in Britain. Even with all these foreign troops, I and my civilian friends were not afraid to be walking outside at night during a blackout or riding our bicycles. Today things are very different.

One evening, I was standing talking to someone at a dance and my future husband spied me. I later learned it was my hair that attracted him. After the dance, I allowed him to walk me home.

Although he told me that he wanted to see me again, I wasn't so sure the feeling was mutual. The next night, he knocked on my door and my parents invited him in. Like all parents, my family were concerned for me, wondering what I might be getting myself into with this Canadian airman. However things progressed and we were married in 1944. We had a typical wartime wedding and as most of the girls did in those days, I wore a suit. If a girl was married in white during those times, it was usually a borrowed dress. To obtain the ingredients for making a cake, we had to collect ration coupons from friends and family. The war brides who married after the war were more fortunate as they did not have to deal with these restrictions.

In 1944, I had my first child Diane who was born prior to my departure from England. (In 1945 I had a daughter Wendy and in 1947 a son Wayne. My husband served with his 405 bomber squadron throughout the war and died in Ottawa, Canada in 1972.)

In the spring of 1945, plans were underway for my departure from the U.K. After my departure from my home in Wrestlingworth, I stayed in London overnight. My parents knew I was leaving but following war-time rules, not even my family was allowed to see me off and this was very difficult for all of us. I was also restricted in what I could bring. Items such as needles and thread and similar items were forbidden as they could be used to create and send messages.

On what would be my last night in England for many years, I spent the night in a Merchant Seaman's Hostel in Westminster. I and other war brides slept in cots and in spite of the rudimentary services, we were looked after by some very nice people from the Women's Voluntary Service. Early the next morning we left the Hostel and boarded buses with blacked out windows and transported to a railway siding. I had no idea where we were. We then boarded a train with a little box lunch for the trip from London to Liverpool. In Liverpool, we left the train and proceeded to board a troop ship. We weren't told when we would be leaving but later that night while I was in my bunk, the ships engines started and the voyage to Canada began. I believe we were probably not quite a day out from Liverpool when we met up with the convoy and the escorting naval ships. The name of our ship was the Mataroa and in 1945 she was being used as a troop ship. During the voyage, every evening the entire ship was blacked out and we were not allowed on deck. In the dark at sea, smokers' cigarettes can be seen for miles.

On board the Mataroa, my cabin contained two double bunks. I slept on the bottom and placed my baby Diane in the top bunk as did the other lady and her baby with whom I shared the cabin. Most of us were very seasick; so much that we rarely went to the galley for meals. The sick bay was so full of people suffering from seasickness that we had to look after the babies ourselves, sick as we were. The North Atlantic in early March is not a place to be in a small troop ship. It was the proverbial 'Trip from Hell'.

Although there were other war brides on board, it was mostly convalescent troops in the lower levels. My cabin was in the centre of A deck. Included in the convoy were many empty tankers, corvettes and one aircraft carrier. On day I watched a plane on the carrier take-off on patrol but with a very rough sea, the plane crashed into the sea. All the war brides were distressed by this until we were told that the pilot had been rescued with only a broken arm. I didn't know whether this was true or not. During the trip I watched another sailor being transferred from one ship to another because of appendicitis. The other ship had the needed facilities to treat him.

After almost three weeks on board, I recall someone calling out landfall and everyone began crying at the thought we were finally going to disembark. During the voyage, we never knew if the constant drills with the crew, troops and ourselves were real or not. Many times we were unsure whether to take our babies out on deck with the weather often so terrible we couldn't see the other ships. Our trip to Canada lasted nineteen days during which I remember the ship zigzagging in the North Atlantic to avoid the German submarines. Two days after we arrived, the last German submarine was sunk just off Halifax harbour. We left England around the 25th of March and arrived at Pier 21 on the 12th of April. I arrived in Ottawa on the 13th of April 1945. I still have my original passport and immigration stamp from the trip. My husband Bob followed on June 28, 1945 - after the war had ended. How different the voyage must have been for those war brides that arrived on the Queen Mary in 1946!

Arriving at Pier 21 in Halifax, some of the babies were sick with measles. These babies and their families were isolated in Halifax. My own daughter Diane who was six months old was fine but she contracted measles three weeks to the day after arriving in Ottawa.

I clearly recall standing in the shed of Pier 21 in 1945 with my baggage in front of me. Disposable diapers had not been invented and during the voyage, we had to wash the cloth diapers. While on board the ship, we ran short of fresh water and had to wash the diapers in salt water. The babies suffered skin rashes constantly. Soon after clearing immigration formalities at Pier 21, we boarded a train. There was little time for sightseeing. Troops helped us on to the train and Red Cross workers offered drinks to we weary travellers. During the train voyage to Ottawa, the train switched to a siding in Levis, Quebec to allow another train to pass. I along with the other war brides went into a little store where we were transfixed at the sight of bananas and oranges, fruit and white bread. White bread had not been available in the UK or aboard the ship. We purchased things by just holding out this strange money. Later the porter told us we had paid too much for our items.

Arriving in Ottawa, I was to stay with my husband's family whom I had of course never met. At the Union Station, my father-in-law received special permission to go beyond the gates and he met me at the train. My mother-in-law wanted to see the baby right away. I seem to recall about 30 persons waiting to meet me. My father-in-law was of English descent and my mother-in-law was French. The majority of my new relatives were French speaking, a language I couldn't speak. I lived with my in-laws until my husband returned to Ottawa in June. The day my husband Bob returned to Ottawa, I went to the station with my daughter and in-laws to meet him.

After some leave, Bob was transferred to Greenwood, Nova Scotia and while he was away, I moved to two rooms in Hull about a block from my in-laws and it was here Bob joined us on his return from Greenwood in the fall of 1945. He was now a civilian again. The three of us shared the kitchen with a lady who didn't speak English making it difficult for me to communicate. In the spring of 1946 we were assigned to one of the houses built for returning troops and their families. There were many war brides and their husbands all doing the same thing. We finally became settled and the long journey from my parents' home in Wrestlingworth to that of my own in Canada was finally over. (A few years later, we purchased this house).

A Postscript:

After my husband's death in 1972, I worked for many years and after retiring I always managed to keep busy with my hobbies and other things. I have made many bibs for single mothers and their babies as well as gloves and mitts for 'Operation Go Home'. I continue to sew for my grandchildren and great grandchildren.

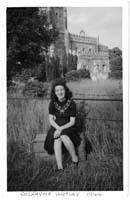

In May, 1989 the 405 squadron held a reunion in Great Gransden, England. I travelled to the UK for the reunion and joined about two hundred people attending from Canada. Luckily, my sister Olive knew the people arranging the reunion resulting in Olive, her family and I gaining inside access to St. Bartholomew's Church and the Dedication service of a Memorial Window on Sunday, May 13th, 1989. This beautiful stained glass window presented from the squadron had already been installed in the church. The men wore civilian clothes. In the stained glass, there are many maple leaves representing the men in the squadron who died on duty. The Canadians also presented a maple wood lectern for the church.

During the reunion, I struck up a conversation with one fellow I recognized who turned out to be a squadron leader. I told him a story about one night during the war when some airmen rode their bicycles down a hill playing night fighters and one of them rode right into me. I asked if he remembered this incident. He didn't recall this event, but we chuckled as he offered his apologies all these years later.

I can recall many details about the 405 squadron. During the reunion there was a fly-by that included a Lancaster bomber, a Spitfire and Hurricane fighter plane. While attending the ceremonies, I met another British War bride who also had lost her husband. Both she and I cried when they played the Canadian National Anthem. I still have the original crew lists from my husbands' squadron that weren't destroyed and I took some of them to the squadron reunion in 1982 where I gave them to some of the men.

Before the war, my husband worked in the Ministry of Pensions and National Health. After the war, he joined Veterans Affairs. Our son Wayne (now retired) also worked there as well. I remember how after the war, many of the soldiers drank and had other health and psychological problems. In spite of the challenges over the years, I feel fortunate to have lived in Canada and to have raised a family and accomplished what I have.

In today's world, I feel the average Canadian does not realize how difficult it must be for new immigrants. I have a son-in-law whose parents emigrated from Holland. In Holland, they had a business but after arriving in Canada, they had to work on a farm which must have been a challenge for them.

I have enjoyed a number of return visits to where my life in Canada began upon landing at Pier 21 in Halifax. Most recently was a visit in August of 2006. Pier 21 has been turned into a fine museum and has truly captured those moments of so many decades ago when we war brides were so grateful to bid farewell to our ships and leave our first footsteps in the soil of Canada.

An immigrant friend of mine from Africa, who lives in Ottawa, considers me a great source of information. Over the years, we continue to enjoy recalling our respective journeys to Canada. Memories are forever.

November 2006