Sobey Wall of Honour

Column

152

Row

21

Immigration Story of Trijn Steenbergen Lopers

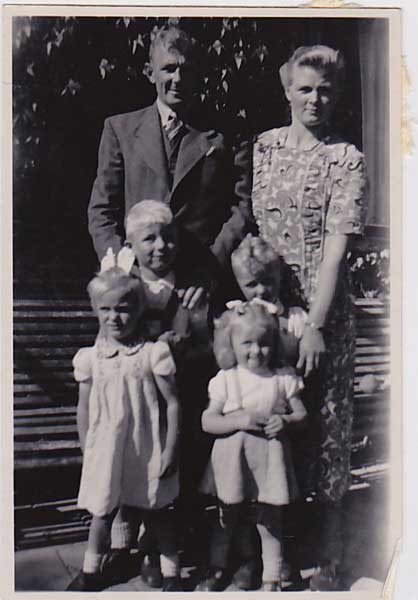

Frits Lopers and Trijn Steenbergen were born and grew up in Koekange, a small town not far from Meppel in Drenthe, an eastern province of Holland. Frits was born in 1918, the fourth of 11 children of Hendrik and Hendrikje Lopers, who operated an agricultural storage and supply as well as grocery business. Trijn was born in 1920, the fourth of eight children of Roelof and Zwaantje Steenbergen, who owned a dairy farm. By the time World War II ended, Frits and Trijn had two sons. They lived with Frits’s parents for a while, and added two girls to the family within two years. There was not much work, Frits raised rabbits. Starting a store in a nearby hamlet was not feasible, and the economy in Holland had few other prospects for them.

Soon there were always meetings in Hoogeveen where they talked about emigration. We never went to them, yet we were the first ones in our families to decide to leave Holland. We first all had to go to Rotterdam to get medical check-ups, the kids, too.

Pretty soon after that we were told about a farmer in Canada who lived in Leamington, Ontario, close to the border with the States, but when he asked about our family, he said he didn’t want little kids on his farm. Soon there was another letter from Canada, with word about a farmer, a single man, in Alma, Ontario, who needed help. His name was Charlie Davidson and he had a house for us. Two families from our village Koekange, (B. Flinkert and A. Rumph) were already in that area and they helped make the arrangements. We had to have a big crate made to put our stuff into: beds, all the clothes, coats, sewing machine, cupboards, plates, furniture, chairs, tables, shoes, linens, and even skates. We made straw mattresses and took those with us, too. A truck came to take the crate to Rotterdam for the ship.

A coach bus took us with all the kids (Hank was six, Jake five, Helen almost four, and Susan was two) and our suitcases, to Rotterdam a few days later. We went with other emigrants from our town at the same time: Bertus and Alie Van Gijssel, Albert and Tina van Dyk with the family, Ben and Jenny Kraal, Roelof van Dyk and Trijn with their two girls. Opa and Oma Lopers and Oma and Opa Steenbergen were able to come along on the bus to Rotterdam to send us off. When we got to the pier in Rotterdam, while we were all standing in line to board the boat, the Van Gijssels panicked that they couldn’t get on board because they had left their paperwork at home in Koekange. They quickly phoned their neighbour, a taxi driver, asked him to break into their house to get their papers off the kitchen table, then drive several hours to Rotterdam to bring the papers to them. By the time the taxi driver arrived, everyone else was already on the boat. It was a close call, but they got on.

We went in a big, old boat called the Volendam on 16 May 1950, and travelled for 10 days. There were not just Dutch people on the boat. The men all stayed together in one room, about 100 men. The children stayed with the mothers, so all four kids were with me. Beds were arranged three high, without rails. One time we were upstairs in the evening and someone said one of my kids rolled off the bed. Some people were seasick; one man vomited overboard and lost his false teeth in the water. We saw nothing but water, water, water, but on the 26th of May we reached the shore in Halifax.

When we landed there was a problem, 5 year-old Jake had been sick with a terrible cough for days. The boat doctor had no cough syrup or other treatment for him, but he told us that our whole family would go off the boat first so he could be brought to a clinic, with the nurses. But only Jake went out, sobbing on the arm of one of the nurses, and they went straight through customs without us. There we were in Canada, not able to speak the language, waiting to go through customs, and worried about Jake. We were brought into a big hall, where we could see the boat through the windows. We learned that Jake was in the hospital in the same building; we could hear someone crying all the time, and that was our boy. It was hard to hear him and not go to him. One time we followed the sound, knocking on the door, when they opened it they told us we had to go right back, waving their hands in our faces that we may not come in. He had pneumonia. It was so hard to leave little Jake behind the door, we tried to call to him to tell him we were still nearby.

For two days we had to stay in a room that had bars, almost like a jail. Ladies and children were in one room, men in another, and at 8 o’clock the gates were rolled closed and locked. We slept on beds, we did not think about bed bugs or what kind of people slept there before us. (Later we figured out that they locked the gates because they did not want parents to be able to leave behind a child in the sick bay.) After crying for two days, Jake’s lungs were better and we could be processed to leave the next day by train to go to Alma. The other families from Koekange had already gone. They later told us they were on a train that was really dusty, and they said they had to clean it before they could sit in it. We got on the train, it was a normal passenger train, not dirty, but it was many miles. We went past small houses, not very sturdy ones, and so many rocks and trees. We wondered what kind of wilderness we were coming to. In Montreal we had to wait for two hours, we could buy some bread there, and the kids got to sleep on the couches in the station for a while. Then the next day on the train again up to Toronto, over Orangeville to Arthur, another long distance. On the train, we were with the Van Arragon family with 11 children. Mrs. Van Arragon cleaned the diapers in the sink that was between the train cars and hung the diapers to dry everywhere around us, over the window curtains and from the racks above our heads.

When we got to Arthur our farmer was there to pick us up. There were three men, one looked very nice and was well-dressed, and Dad went to him, because he thought that must be Charlie Davidson, but he wasn’t. So he went to the second man, who looked not too bad, but he said no, he wasn’t Charlie either. Then the third man, who really looked like a farmer, a bit scruffy, that turned out to be Charlie. He said he had a car, so that was okay, but it was a farm car and it smelled like the animals. He first brought us to his brother’s house, and there we had dinner together. Charlie’s sister-in-law Annie, with the help of another lady, made dinner for our big, tired family. From there they asked us our names, and we told them but they could not say my name, Trijn, so we spelled it and they made Doreen from it. Then we stayed there, but Frits and Charlie went to our house, they got some groceries and later they came to get us out there. The house was not that bad, but there was no sink and no running water. You had to get it from the pump in the back part of the house. There was a toilet in the back, a pit toilet, and we noticed that sometimes skunks would crawl inside. We didn’t know what a skunk was, but when Frits noticed how frightened the grown ups were of a skunk that was walking on the farmyard, he thought he would show them how brave he was, so he kicked the skunk with his wooden shoe. Then we all knew what a skunk was.

It was not so easy to be so far from home. I did not like it at all but Frits said it is going to be okay, everything was there. We had the beds in two rooms, and Charlie in the other bedroom. He lived with us, he was single, around 55-60 years old. He was nice enough, but the language was hard to learn. All night he told us stories and he laughed about them, and then we laughed too, but understand we did not.

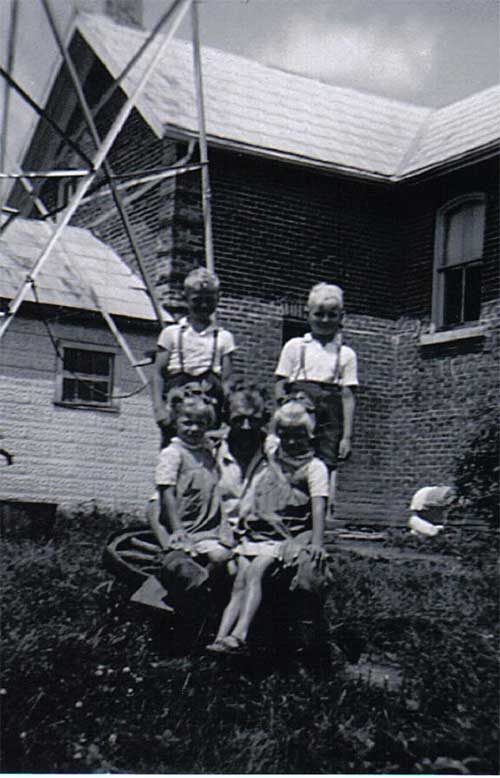

So the time came for the boys to go to school. Hank was 6 and Jake was 5 years, so they went together but they didn’t like it, because the teacher didn’t speak in Hollandse. It was very hard to bring them to school and leave them there, but the second week Alice Rumph came and she walked with the boys to school. When she got up to leave them, they held onto her skirt and cried to leave again, too. Every morning she went with the boys to school, and whenever she made a movement to get up and go home, the boys were right there, too. Then Frits took them to school one morning, told them to stay there, and so they did no more complaining. After the long holidays, it was the same story again, but once Frits told them it was going to be all right, it was not too bad; we were a bit used to living there.

Alice also helped me to clean up the mess when our crate [of household goods] came. It came a few weeks after we did. Charlie and his brother they had to break open the box to get it off the train, it was too big and heavy to carry. They plopped everything on the farm wagon. So from the train station to the house, there all the stuff came, loose on the wagon, and falling off. We unloaded everything and threw it all in a pile in the corner of the living room. Now that was horrible. So Alice came to help clean all that up.

There was a course in the evenings to learn English in Fergus in the first winter we were there, the kids came, too, they liked it because they could play on the blackboard. But we had no car, so Charlie drove us. He would go to a movie till 11 o’clock, and we had to wait because we were busy till only 10 o’clock. It was winter with a lot of snow, and we couldn’t get the car close to the house, so we had to carry the kids through the deep snow up the lane to the house, but Charlie didn’t help carry them. The house had no heat, just a wood stove. One time the horse came walking right into the house and drank the dishwater out of the dishpan. Charlie laughed when I chased it out with the towel.

Every Sunday we went to church with Charlie, he said you buy no car, I go with you to church, and so he did for 6 months and then he said you buy a car. He went with us to church but he did not understand the Dutch preacher, the next time he took a newspaper along and he sat in the car waiting for us. When we went home with somebody after church for coffee, he went along with us and then we went home together again. We later had other people in the car to church, that was Klaas Rietkerk, he lived on the farm behind Alma, we took along one or two from there, and then next there was another family they lived a little farther, they went to church with us, for a year we did like that, then they both bought a car themselves.

Frits’s brother Henk came by merchant ship via New York to Ontario at Christmas time 1950, he immigrated with Joe Vander Veen, a cousin. Henk stayed with us on Charlie’s farm but Charlie didn’t like Henk at his place. Henk also had a farmer to work for, but he didn’t want to leave us to go work for that farmer. Then the farmer came for him and he went after all.

We had Uncle Luke and Aunt Cor Lopers living with us in the winter at Charlie’s, they came in February, a few months after Henk, and had no place to go. They came with my cousin Jan Steenbergen on the same boat. So they lived with us for four months, and in the spring they went to the Niagara Falls where they had work in the hotel.

We stayed at Charlie’s place for three years. It was hard work, sometimes there was not that much to eat. Once I cooked horse meat, but I couldn’t tell Charlie, he would not eat horse. So I told him it was beef, and he loved it! A hunter who lived down the sideroad would sometimes bring us food that he killed: a deer, rabbits, or pigeons. John was born in Fergus in 1951. Eventually Charlie couldn’t pay us anymore, so we decided to move. Then we moved to the farm on the road across from the Berea Mennonite Church on the Elora Road, across from Albert Rumph. We stayed one year, we had chickens in the barn, but there was no water in the house so we brought water from Alma for drinking and cooking, but for washing and for the barn we hauled it out of the creek. Just a cookstove in the house, that was all we had in the winter for heating. We were sleeping upstairs with three boys and two girls.

When we moved to that farm, the kids went to school at the corner. Frits worked in Elora at a furniture factory, and he would bring the water home from Alma every day. But after one year we moved to Mossley, near Ingersoll, where the farmer McKenzie lived, and Frits worked for him. We were living in an old school, it was lots of room for us. There Alice was born in 1954, and Rosanne was born the year after. The year after we moved to our old place again, Drayton, where Albert Rumph had a place for us on the corner of the 6th. First we stayed for a week in a house on the 3rd line. And Frits worked at the tileyard in Wallenstein. And after two years we moved again, finally to the farm we bought outside Drayton across from Jack Samis. A lot of moving for the family in those years, with all the kids and babies, lots of packing and unpacking, and cleaning.

There we built the barn into a chicken barn with 4 floors, where all the chickens grow. The feeding had all to be done by hand, we had 15,000 chickens over four floors, but we ran out of water so we had to drill a well, but that was lots of money involved. But we had a good mill owner, Thompson, he said you build a well, and he give us the money for it all and we started farming. Frits to the tileyard every day, Hank was helping me in the barn and feeding and so forth, he did not go to school. We had some pigs in the shed by the barn, we had a cow what Hank had to milk, and some calves in the field for fattening. It was hard to get some money together, to get ahead. Later Hank went to school with the other kids, Jake, Helen, and Susan. But it was a year since Hank went to school and the teacher came to us to speak about him, that he was making trouble in school, he got his work always done, and was fooling around to make fun, so then the other kids couldn’t get their work done. So then he came home again, and went with his dad to work with the wheelbarrow in the tileyard. Later he talked to his brothers do not fool around in school, otherwise you have to go to the tileyard, too. Richard was born then in 1958 and Edward in 1960 and Lois in 1962.

Eight years after the family purchased their own farm and started raising chickens, Frits passed away of lung cancer. Doreen stayed on the farm with the ten children, learning the business and keeping it all going. She retired at the age of 60 and moved into Drayton.