Sobey Wall of Honour

Column

17

Row

9

The Sea and the Northern Lights

The Second World War was a difficult time for many, and for young "inlanders" like me there was the added frustration of not knowing what the ocean looked like, despite the important naval battles being fought. But there I was, 21 years of age, and finally I had the chance to get my sea legs. It was just before Christmas, 1950, when my immigration formalities were complete and I could leave Europe to start my new life in Canada. The United States, first choice for all of my fellow refugees, was out for me, since I had no sponsor there. Fortunately enough, I did not sign up to go to Australia, since the refugee transport ship I would have been on blew up some 200 miles offshore and there were no survivors!

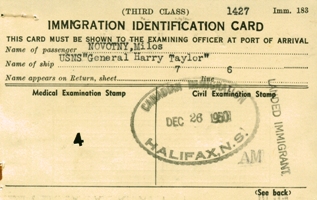

My friends all departed just before me, and feeling lonesome, I was really excited to finally board the train for Bremerhaafen to start my ocean voyage. As my immigration card indicated, my ship was the U.S. Navy small transport vessel, General Harry Taylor. Since it was only about an eight thousand ton ship, it was rather crowded with its regular crew of 100 and some 300 refugees who'd been sponsored by the International Refugee Organization (IRO). It was an emotional experience to see the shores of Europe disappear and to feel the rolling of the ship for the first time. The winter Atlantic proved to be very unfriendly, and many travellers went through extreme misery. I have always been fortunate to have a high tolerance for motion sickness, but even so, on at least one occasion, I came close to a true "mal de mer".

By the time we reached Halifax and saw the shores of the new world for the first time, we were two days overdue and minus two old ladies who died of dehydration and had to be buried at sea. The Atlantic can be rough in any winter, but that Christmas was the roughest in years. When we were mid-way through our journey, the waves and swells were up to 60 feet in height and the upper decks were continuously awash. Being a healthy young male, I was quickly recruited to serve as ship's police, making certain that no travellers would appear on deck and risk being swept overboard. To aid me in my task, I was issued foul weather gear and was tied down to the railing, so I myself didn't disappear. The small ship pointed its bow skyward, only to tip the nose down into the next watery mountain, getting totally submerged. The stern would come up first, leaving the props to spin in the air, producing the most frightening vibration throughout the vessel. It was followed by ungodly curses of all the crew, giving me my first on-the-job training in the fine art of English expletives. Still, getting the salty spray in my face was quite an experience, something I did not taste again until I took up sailing many years later.

Life below decks was a different world again. Most of us greatly enjoyed the feeling of climbing the ladders while the ship was in the process of diving, giving us the thrill of running effortlessly the whole flight, yet in reverse direction, when the ship was rising, we would end up struggling with full force to walk down. These plays with gravity could also be unpleasant, for instance, when people had to take turns upchucking into the empty oil barrels tied down in the gangways. I saw one youngster leaning in to add to the contents, when the ship heaved and he ended up falling in headfirst. Fortunately, his father quickly pulled him out by his feet, but cleaning him up was a much more difficult task. Needless to say, despite the plentiful food, very few people had enough hunger or stamina to try to feed themselves while the trays were sliding back and forth with every roll. Celebrating Christmas was out of the question with everyone so seasick; in fact, we didn't even notice any decorations -- although perhaps they were not allowed by Navy rules in those days.

Finally we reached the Port of Halifax on the 26th of December, 1950 and happily set foot on the famous Pier 21 where so many immigrants were to land. I still recall a funny performance by a young fellow traveler, who later ended up working with me in the bush on the same immigration contract. Each of us had been issued a suitcase by the IRO prior to departure, but he had accepted it despite having no worldly goods to put in it. To make it interesting, he pretended to have to struggle to carry it and lift it for inspection, only to reveal a solitary toothbrush as the sole contents. Unfortunately, the customs officials did not find it very amusing and the poor fellow, an ex-mailman, got a tongue-lashing.

Halifax was also our departure point for our train journey to Northern Quebec, which gave us a full day of sightseeing. A kind local citizen with a large station wagon showed us around Halifax for free -- what a difference in the city when compared with its appearance some 30 years later!

While we were visiting our first city in Canada, we also got the chance to do some North American "shopping". I happened to be the rich fellow in our group, having saved some of my U.S. Army tips. In fact, I arrived with a fortune compared to others -- I had $28 in my pocket and even managed to buy my friends their first Canadian chocolate bars.

Later the same day we were escorted to a reserved train car and our contingent of beginner lumberjacks was now on the way to our destination near James Bay -- Camp LaViolette. The group consisted of some 60 young Europeans: 30 Hungarians and 30 of mixed origin: six Czechs, some Yugoslavians and a couple Poles. We had all signed an immigration work contract for one year, a condition arranged by Canada and the I.R.O. The choice of employment I was given was reasonably easy: I quickly accepted the challenge of the Far North, having read Jack London's "White Fang". My other choices were Coal Miner or Farm Hand. Yet as we later found out, many of the refugees were easy targets for exploitation no matter which occupation we chose.

Our first impressions of the new country were overwhelming, mainly because of the vastness of the thinly populated land when compared to Europe. The train took us to Quebec City and then to Senneterre, a whistle stop in Northern Quebec. When we arrived there were two buses waiting for us, both showing the company letters "C.I.P.", for Canadian International Paper. The Hungarian group was transported to a separate lumber camp, and my group to one owned by a sub-contractor, Mssr. Lafontaine. The trip and the scenery were tremendously exciting as we travelled about 200 miles north toward James Bay over frozen, dirty logging roads, only usable because of the frost.

The first stop was in the Central Depot where we signed in and were issued all clothing and equipment on credit. When we reached our own camp, we found out that our cabins were not quite ready; without any skills we still had to complete the walls and some insulation! The horses, I'm sorry to say, had much more attractive housing than we did, and insulation was indeed essential as we soon found out, when we experienced temperatures of minus 63 degrees Fahrenheit for three days -- very close to a Canadian record. All one had to do was to take a careless sniff through the nose and both nostrils would freeze shut. Frostbitten cheeks and noses were commonplace.

Once we settled down and were assigned our bunk beds, we enjoyed the heat produced by a small potbelly woodstove with a long, hot pipe which warmed everyone enough to kick their blankets off. However, during the night most of the 12 fellows per cabin would quickly pull them back on when the fire died -- that is, if they could, since quite often the blankets would freeze to the walls, covered with condensation.

Taking care of our bodily functions was a problem of its own. A hut with an open pit served as a latrine, but to really appreciate such a facility, you have to experience it yourself -- at 63 degrees below zero with a brisk wind to boot. Such hygiene measures were hard to accept. At night the camp was full of the beady, shiny eyes of marauding wolves, so most of us hardly stepped out of the door to take care of more minor elimination tasks. Fortunately enough, our water supply came from a frozen creek up the stream, usually consisting of chunks of ice which we melted down for drinking water, as well as to wash our faces and hands. It became somewhat more critical in the early spring when we were more concerned about the safety of the water supply since one of the poor horses pulling the sled with the barrels and pails dropped dead at the bank and was only removed many days later upon my insistence.

Wildlife was sparse, short of the wolves. Those little devils even once ate half our meat shipment, devouring two hindquarters of beef, when it was left outside the kitchen overnight following a late delivery. In fact, one of the pieces was dragged away some 200 feet -- I do not know how many wolves had to co-operate on that one. Other members of the animal kingdom were moose, huge and astounding for European newcomers. The first one we saw was being skinned and butchered in one of the native Indian camps we encountered on our early trek. Later we saw quite a few while working. Fortunately we weren't accosted by any bears because they were hibernating at the time. However, we did have a lot of fun with ptarmigans, very brave members of the northern wildfowl family who often would land on our heads, defending the territory we were invading. They were not familiar with Man, and at least one paid for it with his life. One of our fellows thought the chicken-like bird might be a pleasant change to our diet. It turned out to be too lean and tough as nails when we tried to roast it.

Along with the extreme climate, our daily nutrition also took some getting used to. Our diet consisted largely of beans and sausage, along with daily servings of rich apple pie. Hot tea and hot chocolate were our only beverages. Coffee was not very popular, and milk, of course, was only reconstituted from powder. There was no alcohol allowed since we were in native Indian Territory. We quickly got used to the feeding habits of the French Canadian lumberjacks who wasted no time in consuming the largest number of calories in the shortest possible period, after a quick prayer and grace-giving which at first we found rather strange. The kitchen and the dining huts became the sight of another one of the more unusual experiences of my life.

When the only cook for some 60 lumberjacks became ill and had to leave, we were asked if any of us could take over. One Czech fellow was a butcher at home and so he felt he could take care of the meat preparation. However, he needed a "second cook" and by acclamation that turned out to be me. I recalled observing my mother baking cookies, so I assumed I could create some of the pies in daily demand. When I agreed to participate, I quickly discovered that I was to become the chief cook's underling, which meant starting the stove fires and doing the overall kitchen maintenance. I thought it was better than the cold lumbering work, but my reprieve didn't last long. When I prepared my dough, it was just flour, sugar and eggs, mixed with a bit of milk. I carefully fitted the flattened dough into aluminum plates, topped it with defrosted apple chunks and baked them until just slightly brown. However, I was ignorant about the essential element of plate greasing, and when the apples melted down they made perfect, cement-like glue instead of pie. The outcome gave me the opportunity to hear my first sparkling French Canadian expletives, when the rush-rush approach of the locals was delayed by the ripping, tearing and scraping of their favorite dessert. To the screams of "Mon Dieu" and "Tabernacle", they tossed the half-empty plates across the room and charged out cursing. Such was my short-lasting new career, as the next morning a substitute cook was brought in from the Central Depot and I was asked to pick up my axe and go back to cutting down trees.

The learning process in our immigration bargain was rather difficult. Despite all of us declaring that we knew what to do, we had to observe the "professionals" to avoid injuries since our brief instructions were not really sufficient. When we donned our lace-up boots, put on our lined gloves and red hunting caps, we looked like real lumberjacks, but we learned the ropes very slowly. On very cold days we often ended up with frozen noses and cheeks, and since the supply depot did not have any "ski masks", or "balaclavas", we sacrificed our pants, pulled a cutoff leg over our heads, making holes for our eyes to peek out. It lessened our suffering, but somewhat limited our vision (and our wardrobe!).

In the long run, none of us ended up with any serious injuries, only occasional axe cuts in the shins. However, most of us endured enough pain at night. No one used power saws in those days, so the physical labour was intense. We were expected to produce 12-foot logs which were tallied and remunerated by nine cents a piece on our account. Quite often we would end up with 25 to 30 logs each by the end of the day, although the experts would manage 120 to 150 a day. The impact of the axe on frozen wood resulted in traumatic hand joint arthritis which would make us wake up screaming during nocturnal muscle spasms. In addition, our lack of skills led to frequent problems with our saws and axes, when the blades would get imbedded in tree trunks or the shafts would fly away from our inexperienced hands when striking frozen wood, getting lost in deep snow drifts. That meant paying $2.25 for replacement of the blades, often in addition to the lost tool itself. With our personal debt rising rather than declining, we were really trapped and felt exploited, even after we became more adept in our work.

When the situation was reaching the boiling point, I was asked to become spokesman for the group, being the only one fluent in French at the time. The daily charges to the refugees were adding up, including $1.50 per day for our "accommodations", and $2.00 a day for food. When our production tallies shrunk, we looked up our immigration contract and found that is said we were to be "employed in conditions identical with the local work force". However, it became clear that we were being assigned strips of forest where the trees were not large enough to qualify as logs, which had to be at least four-inches in diameter at the smaller end. Indeed, we were being used to clear parts of the bush to haul and stack lumber produced by the locals, while our trees looked more like Christmas trees, too small to count.

Finally one morning the refugee group simply refused to go to work, and in fact we had a strike on our hands. I found myself in yet another role, as strike negotiator. After two days, we suddenly heard a new sound in the clear, frosty blue skies: the sound of plane engines. The arrival was unexpected, but we soon found out that a representative of the Quebec Department of Labour was on board, brought in to help us with our difficulties. And help he did. After a brief tour of the facilities and some questions to my colleagues, we met in Mssr. Lafontaine's office and I was taken aback when our contractor got a thorough tongue-lashing in my presence. The official was appalled by the blatant injustice of our working conditions, and within a day we were intermixed, one strip for the immigrants, one for the regulars, all back at work together. The situation remained satisfactory until we moved camp to a new location, where the exploitation reoccurred, and a second group strike necessitated another visit from the Department of Labour. By then the government agent knew me well enough that he urged me to clean up my debts and get out as soon as I could. He knew of my long term ambitions, and warned me that if I kept up the trauma to my hands I might be unfit to practice fine surgery in the future.

The move of the camp was yet another exciting experience. Several bulldozers worked hard on clearing a "road", strips of flattened ground over the frozen tundra, possible only during the severe frost period. The prefabricated huts were then shifted onto long, thick logs, and were dragged to our destination while we walked alongside or occasionally got a short ride on one of the logs. Finally we reached a new site and arranged the huts in a circle around the kitchen and the mess, as well as the boss' cabin. Lastly we built new latrines, when nature called rather urgently.

The hard work made for short evenings back in our quarters, although we did take time to exchange some personal stories. One big difference between the local lumberjacks and the immigrants was our differing ideas on maintaining personal hygiene. Sunday was everybody's only day of rest, which most of the locals spent on their knees praying in a makeshift altar in one of the cabins. Occasionally a priest would visit and bless many or most of them. Yet, the "crazy Europeans" would insist on a bus trip to the Central Depot where all 60 of them would spend the day rotating through the only existing shower. The hot water flow was continuous, provided by a pump from a large holding tank through a wood-heated system of pipes. We almost felt like exotic animals on display to the local population. I guess we were a true oddity when other men would arrive in the late Fall and in most cases remain until the Spring in the same set of long johns, day and night, unless they fell apart, when they would simply be replaced but never washed. The primitive life was hard to accept, yet gradually we got used to it and even grew to like it, especially when the old-timers would sing and dance, while others rocked on homemade chairs, rolling cigarettes, often by one hand, and showing off their super accurate spitting skills into homemade cuspidors.

Yet with all these new experiences, one was paramount and most overwhelming. Unless we had an occasional snowstorm, practically every night we would be awestruck by one of Nature's best shows: the beautiful Northern Lights. We saw every colour of the rainbow in soft, fluffy waves, or witnessed rapid bursts of stripes of various lengths and thickness, which hovered motionless, only to be replaced by flowing walls of shimmering columns. No man could ever come up with such an impressive display and we were so impressed we put up with all the shortcomings and unpleasantness of our work just to enjoy it.

And there was a lot of cruelty at the camp, such as the senseless torture of the horses, who were often viciously beaten while trying to haul logs on sleds hopelessly stuck in deep snow and hidden stumps. It was only on Sundays we appreciated the joy of a free day for the animals, when we saw for the first time that horses could jump and roll, full of life when freed from their labours. They behaved more like puppies, despite their huge size. I guess that's life, and most of them did survive, despite their suffering.

Well, finally the day arrived when our company debts were met and we could consider leaving the "C.I.P". Having discussed my immigration commitments with the Department of Labour official on at least two occasions, I was reassured that I could complete my contract elsewhere, as long as my services were required. And what else could be more appropriate than a hospital for an ex-medical student. I found out that orderlies and operating room technicians were in demand, so I got in touch with my friend Vera in Toronto -- we did in fact have some postal service, albeit slow and often delayed. Apparently St. Michael's Hospital was in need of staffing and that became my next goal. Indeed, after completion of my 12 months of work in a "required site", the hospital was recognized as an appropriate site to complete my contract. Ultimately I did receive a thank-you note from the government for keeping my part of the deal.

Back at the lumber camp, May had arrived, with longer days and a much kinder climate. Our work output was greater, perhaps due to the acquired experience as well. Once the bills were paid we could leave, and we even had a few dollars left to our name. The local lumberjacks were due to depart at the same time, many of them with enough money to buy a car, live it up during the summer, or take care of their families, only to return the next winter for more of the same.

The trip out was really exciting for all of us, especially for us the newcomers. The winter "roads" had now become rivers of mud when the frost disappeared, and the only way out of the bush to the train stop at Senneterre was on top of an open truck. A dozen of us would frequently dismount to jump into pools of mud trying to pull out our truck by hand when the wheels got hopelessly stuck and spun in vain. We even had a chance to see some of our own logs floating down the St. Maurice River at our side. None of us will forget those impressions of the Canadian wilderness, bursting to life in early spring.

After boarding the train and a brief stop in Quebec City, I had a chance to spend a day in Montreal where I admired some skyscrapers for the first time. Shortly after I met my friends in Toronto and started another chapter in my exciting New World life.