Sobey Wall of Honour

Column

69

Row

2

Dutch Coalminer becomes National Parole Officer

In 1946, at age 14, I was eager to get away from it all. Living in an industrial area in the south of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, we had come through the war with little or no harm. My parents had done their utmost to shield us from the negative effects of the war. Dad worked in the coalmine since 1937, and by renting some acreage, we grew our own food. We did not need to buy bread, potatoes or vegetables. With four chickens, we even traded eggs for such a thing as a spinning wheel. Mom was an avid knitter and seamstress. With a sheep and two goats, I practically grew up on goats’ milk. At times we also had rabbits and a pig. Only later did I learn that the Nazis could have confiscated the meat, because a permit was required to butcher anything. They could also have shot my parents for fostering Carrie, a Jewish toddler. My wife on the other hand, who lived in a city, was eight years old in the winter of 1944-45 and slowly turning black from the lack of proper food.

As a rebellious young teen, I wanted to get away from everything. The future was rather bleak, for the outlook for coalminer’s sons was to follow in their dad’s footsteps. Social rules, customs, controls and expectations were too repressive to my liking. Nothing ever changed, no matter what you did. I had no learning problems, because in elementary school I was usually the best in class. But having to study in high school outside school hours or during my free time, made no sense to me. Moreover, what is the use of learning algebra, historical dates or even physics and bookkeeping when you will still end up working underground.

Emigration was a very attractive idea. I was ready to take on anything anywhere else and accept all the consequences of my actions. My parents talked about the U.S., Canada, Australia and even Argentine. South Africa needed coalminers, but we wanted to get away from the mines.

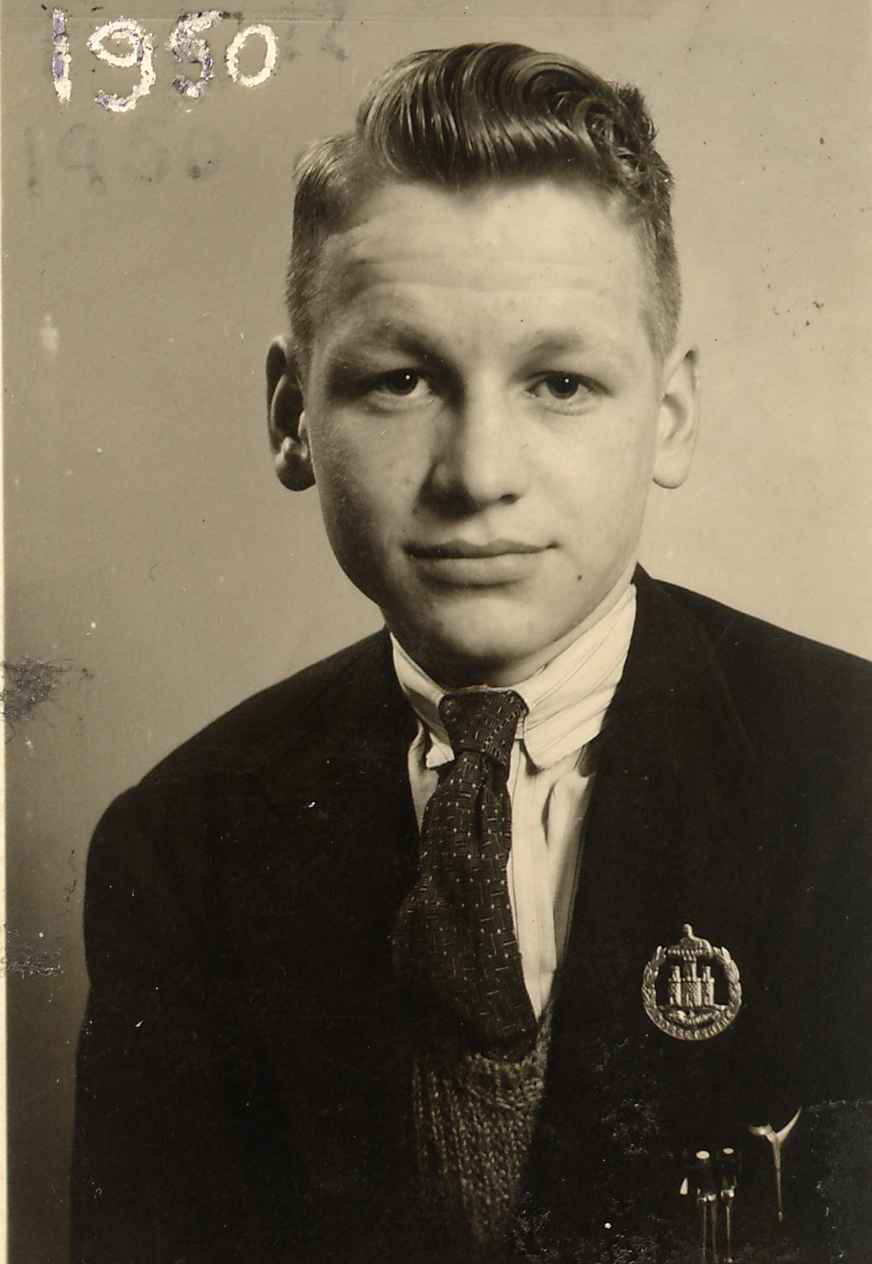

In 1948 my older brother by three years, wanted to become a pilot when he was to be drafted and so our emigration plans were scrapped. Mom spent her savings on new curtains and the like. Even though I had twice failed a grade, I had to stay in high school. So I went through the motions. Having fun, playing around and pestering teachers became my thing, but it did not make me happy. As expected, I failed the finals in 1950, and at age 18, I started to work in the coalmine. Others had first taken on other jobs, but eventually they all ended up working down below where the money was. Even though Dad’s stories about the low work spaces made me feel scared and choked up, I decided to take the plunge and go right away underground. Miners were the best paid labourers in the country and it would take money to set up my own family home. That seemed to be my major goal. Since age 16, I had my eye on a girl from a church, 25 km away. I would see her only twice a year at meetings. She was 6 months my senior and we finally clicked after we both turned 19.

In 1952, my brother completed his tour of duty in the army. The air force had rejected him due to a weak eye. After working a few months at a chemical plant, he applied for a study visa to the U.S. Two months later he was gone and he managed to stay there by marrying a Dutch-American girl. With my two younger sisters, the family applied to immigrate to Canada. We figured that a farm in southern Alberta might be a possibility. More importantly, there was a church at Lethbridge with the same basis as ours and that was the Canadian Reformed Church. However, emigration was twice rejected.

In 1953 I applied by myself, because at age 53 my Dad was no doubt too old to emigrate. However, I was rejected as well even when I applied a second time without subsidy. When I learned that fellow workers, who had applied to other countries, were also turned down on the same date, it became quite obvious that the rejection came from the Dutch authorities. The government owned the largest mines and even had to recruit workers from Poland and Italy. Sons of miners would no doubt make better candidates. In the mine I soon secured a job moving electric lights. I worked by myself on an early midnight shift from 8 pm to 4 am. My supervisor was on dayshift. He just read my daily reports and might inspect my work once or twice a month. As a rule, only accomplished miners with five year experience held such a position. I was still a student, but apparently they viewed me capable and responsible enough to do the job. After all, coal gasses and electrical sparks make for explosive situations. Emigration, however, had once more been refused.

So after four years in a mine of 4000 underground workers, I quit and took a live-in job on a farm south of Rotterdam. It paid about one-third of a miner’s wage, but one day each week, I could attend an agriculture school. After I moved to the farm in August 1954, I also secured a suitable job nearby for my fiancée from Maastricht. However, she got cold feet and our relationship eventually ended.

In November 1954, I applied again to emigrate to Canada, but now as a farm labourer. It was approved a few months later. I also met a 17 year old girl, Annie van der Zee. She was a member of the church in town, Zwijndrecht, and a friend of the farmer’s daughter. We had a few dates, but Annie agreed that establishing relations at this time was not a good idea. Nevertheless, when I went home one month before leaving for Canada, both of us started to write letters. In those days, we did not have telephones. We just felt like sharing our thoughts and lives. We kept it up for three years. She followed me in 1958 and we were married in 1959.

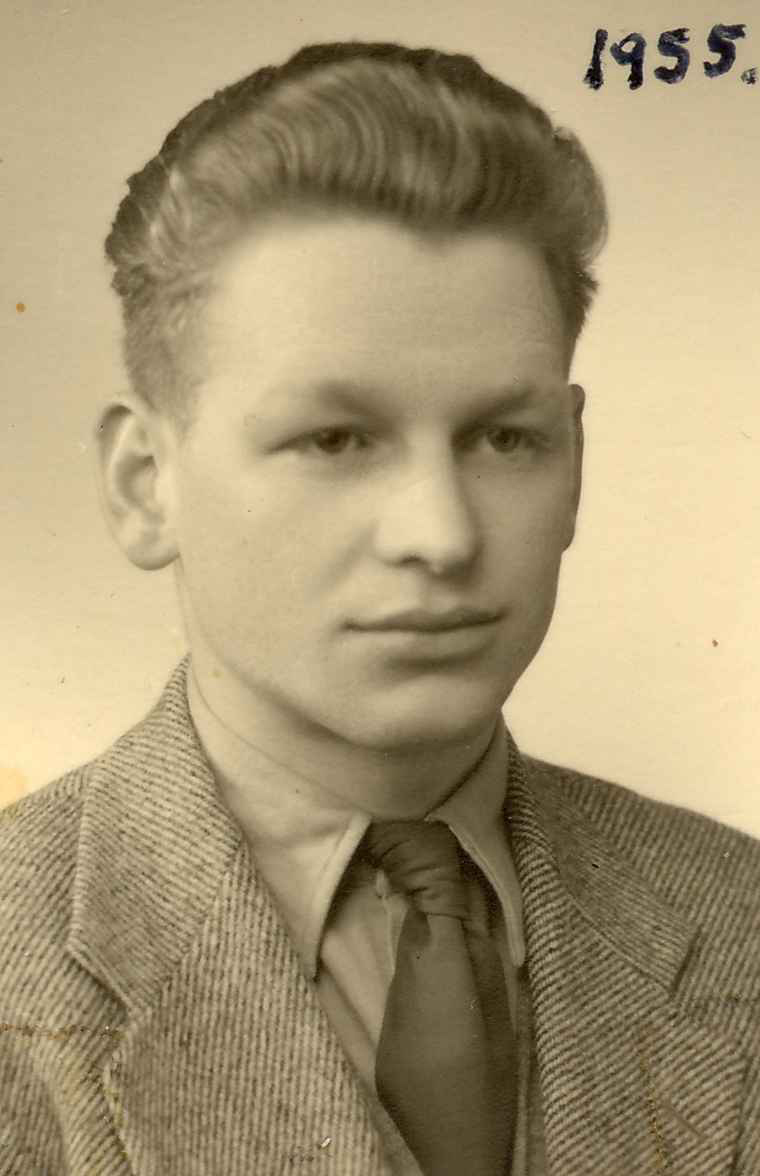

On June 17, 1955, I boarded the SS Groote Beer. A nine year old dream had come true and nobody could get me to cross the board walk until I reached Canada. Everyone felt that North America was another world with no hope of return. That Friday night we sailed from Rotterdam harbour. At evening devotions with the Rev. A.B. Roukema, the ship’s chaplain, I ended up playing the piano for a hymn sing. After all, I had been the only organist in a small church with a pump organ or harmonium since I was 14. On Sunday morning we stopped briefly at Le Havre, France, to pick up more passengers. The boat trip lasted seven cold days. For two days I was sea-sick and lived on biscuits. With a few others we soon formed a group to hang out with. Nevertheless, I often spent time playing piano in the empty auditorium down below. I also enjoyed the fresh air by hanging over the railing watching the waves and feeling the cold, wet breeze in my face. I always liked biking in the rain and now the rhythm of the waves were accompanied in my head by music and by musings about the promising emptiness ahead of me. Leaving the past behind had almost become a natural thing to me, for I never had regrets about the past as I always looked forward in trusting faith. I had grown up believing that in His love of creation, God promised in His grace to also be my Father, who forgives my sins in Christ, His Son. I knew for certain, that this covenant God was faithful and that He would never abandon me. Therefore, I could always go on in trusting confidence.

The slow approach to Halifax harbour on Saturday, June 25, 1955, was rather agonizing. A rocky shore hidden in fog crept slowly by. It must have been quite foggy, for I cannot recall having seen the city against the hills, as we saw it 50 years later on a trip. I do remember the large hall, Pier 21, and the awaiting train. In the hall I had located my crate (1.5x1x1 meter), but not the duffle bag. Somehow none of us could come up with the English term for it. We boarded the train and settled in. Looking out, we saw a hand-cart rolling by and loaded with luggage. On the very top I spotted my duffle bag. At least it would not end up in New York and I could right away go to work, because my work clothes and shoes were in it. The crate would arrive six week later. From brochures in the Netherlands, we had learned about life on the prairie. One had to be resourceful, self-reliant and independent. Neighbours might live many miles away. I was prepared and looking forward to such a life. I always enjoyed times of solitude. I had brought a first-aid kit and even a sewing kit along with blankets, sheets, clothes and high boots that proved useless in the cold weather. With about a hundred books, mostly bible-study books, and a pile of piano and organ music, I was ready to live alone and never feel lonely or bored.

On the train with wooden benches, the cold-water tap and pointy paper cups were a refreshing luxury. The countryside slipped by in the darkness: trees, trees and more trees. Early Sunday morning we arrived in Montreal and the train would not leave until 8 pm. Four of us toured the neighborhood, taking pictures and staring up at old buildings and Mount Royal. At a restaurant, a waitress tried to impress us with her knowledge of Dutch by saying: "Ik hou van jou, liefje" (I love you darling) and then she wondered what it really meant. On the train we tried to sleep on the wooden benches with lowered table tops. The train chugged along lakes, streams and forests. By morning the tracks wound through cut-out rock and it was picture-taking time. Here and there the train stopped long enough to let us dash to a store and buy some bread, peanut butter, jam and such. In Winnipeg we had to register at the Immigration Office on Higgins Ave, two blocks from the C.P. station. I still had more than a hundred dollars. A taxi took a few of us to the C.N. station on Main Street and we started to cross the prairie. By midday the temperature was unbearably hot. I ended up sticking a table top out the window to catch a draft of air. That did not last long, for our faces soon turned black from dust and locomotive smoke. Sometimes the train stood still for a long time in the middle of nowhere. We saw prairie without end and very few trees or none after Regina. Friends from the boat had gone on to Edmonton and Vancouver and in Medicine Hat the last one went on to Calgary. I was alone for the final hundred miles to Lethbridge. That trip took us only an hour.

The immigration fieldman was on his honeymoon, so the church pastor met me at the train station. After supper at his place, the Rev. G.Ph. Pieffers took me to a Dutch farmer in Barnwell. They had two daughters and four sons my age. I worked along with them for free room and board. Without anything to worry about, I felt like being on vacation. I enjoyed everything new and strange. Three weeks later, the fieldman took me to a job forking bunches of green peas into a threshing machine from dawn to dusk for 50 cents per hour. We slept fully clothed on steel-spring cots without a mattress in a single-walled, mud-floor, garage-type shed. We washed ourselves at the hand pump in the yard. Only after working for two hours did we get breakfast at 7 am. I ate piles of pancakes. On Saturday afternoon and Sunday, I stayed at the home of the fieldman, Gerrit and his wife Wilmie.

During the second week of threshing green peas, Gerrit’s friend, Egbert, showed up. He took me during lunch hour to a job interview in construction in Lethbridge. He promised to get me back on time, but when I could start on the spot for $1.25/hr, he said he’ll pick me up after five. I protested, but he said, this is the Canadian way and my previous boss would understand. I sanded plastered drywall in newly constructed homes. Another couple in town gave me room and board. To have my own transportation, I accepted an offer to buy my first vehicle, a $25 bicycle. Two weeks later the employer moved to Calgary and I was laid off. Just outside town, manpower found me a job at $1.10/hr. It was a rock crushing plant. With a large sledge-hammer, I had to smash large rock through a 6-inch-square grating. It was hot and dusty. A conveyer belt then dumped the pieces in various crushing machines, turning them into 50 lbs bags of powder. About three weeks later an early snowfall in the Rockies ended the operation. I found a job, spreading gravel by wheelbarrow in an underground parking lot of a shopping mall.

No sooner had I loaded my first wheel barrow on that Monday morning or our pastor came down the ladder looking for me. He took me 60 miles north-east to Vauxhall for a more permanent job. He said that ‘old man’ Kobes had declined his job transfer, because he would be away from his family all week. I started the next day as a seasonal farm labourer at the Irrigation Substation of the Federal Experimental Farm in Lethbridge. In case of a lay-off, I had resolved to work during the winter in the Lethbridge coalmine, but I never had to do that. On the weekend I stayed again with Gerrit and Wilmie, who did my wash and mending. I could also attend church and the evening meetings of the bible-study youth group. On Monday mornings, during that first winter, I started hitch-hiking at 5 am regardless of weather conditions. Somehow I was never late for work. On Saturdays we worked until noon. On my way ‘home’ in the afternoon, I stopped at two addresses to give organ lessons to four young students.

Living on the job in a bunkhouse with hot and cold water as well as showers, was an unexpected luxury. With eight others in the home, I had a double room to myself, so I brought my harmonium. I had found that old pump organ in a garage in Lethbridge. It was all in pieces with the screws in a tobacco can. I offered to buy it for $15.-, providing there were no missing parts. So it was fixed in a week between jobs. Usually I was alone in the bunkhouse, for after supper others would take in a movie or go to a bar in town. Neither interested me. I wrote letters to my girlfriend overseas and I enjoyed my time reading, playing organ and drawing pen or pencil drawings.

After working with a carpenter building a house on the premises, I was told one day in early November to clean up, change clothes and report for work at the office. I was shown how to use electric and hand-operated calculating machines. Moisture readings of thousands of soil samples had been gathered during the summer along with yields at various levels of irrigation. All these figures had to be expressed in percentages, tabulated and certain calculations had to be presented in graphs. Twelve of the other 15 regular workers had been subject to the seasonal lay-off. Miraculously they kept me on through the winter, even though I had only started two months earlier. The job developed into helping out in research projects, work in a lab drying, grinding and weighing crop-yield samples etc. I also had to draw graphs. So I enrolled in a correspondence course in general drafting. It was even suggested that I attend the Edmonton University for a two-year program in Agriculture, but I could not consider that. My parents and sisters counted on me to sponsor their immigration. They arrived in Canada in early May 1956 and for two years they signed up for hoeing beets. Just before they arrived I bought my first car, a two-door 1953 Plymouth. Our church community was 50 miles away and 20 miles from my parents’ home. The next spring they bought their own car, a 1949 Ford. Trying to farm in this irrigation district, required an investment we could not afford.

In 1957, I decided to get a drafting job in Vancouver. A family from our home town had just arrived with their three young children. Harry wanted to join his friends at the west coast. We put their stuff on the train and stepped in my car. It was an impressive trip through the Rockies. The family secured a home in Surrey. We worked a few days at a millionaire’s ranch near Langley painting buildings and hauling hay. Then we worked a few weeks at a lumber mill and a hydro-pole plant in Richmond. In Greater Vancouver I soon found out that too many draftsmen with experience were looking for jobs. After living on my own for a while and running out of money, I joined a friend, Piet, whose employer needed an electrician-helper in home construction. We also spent two weeks in the wilderness near Golden, wiring cabins for workers who were to construct the Roger’s Pass. Again I experienced and learned a lot. That fall, I picked up my two sisters from Barnwell, Alberta for winter jobs in Vancouver.

With my girlfriend on the other side of the world, I filled my spare time by peddling made-to-measure shoes and suits from Montreal. Later I sold stainless-steel cookware sets that were at that time not available in stores. I had little or no success as a salesman. However, these things gave me an opportunity to get to know every family in the church community at New Westminster, where I had become the harmonium-playing organist. We had converted an old cinema on Kingsway into a church hall.

In 1958 Annie’s parents allowed her to emigrate before reaching age 21. We had corresponded for three years - one letter every other week, like clockwork - no personal contact - no telephone contact but just long letters. I met her at the train station in Regina on Sunday May 4, 1958. After visiting my parents for a few weeks in Barnwell, we drove to the west coast. I had lost my job as an electrician-helper, but a friend found Annie a job as a home-maker. During the summer school holidays she picked beans on a farm with her friend’s sister. Eventually I accepted a door-to-door delivery job of eggs and poultry, and I bought a station wagon for that purpose.

We planned to get married in March 1959 and turn the upstairs at Gerrit and Wilmie’s into our apartment. They had also moved to the coast. We were ready to buy lumber for building kitchen cupboards, but the lumberyard had closed at 1 pm. That same Saturday evening I received a telegram from my parents. They lived on a farm in Carman. A son-in-law-to-be was to farm it, but that did not work out. Therefore, they said, this might be my chance of a life-time to become independent. After an agonizing Sunday, we cancelled all our plans and decided to start farming. My car was traded in for a half-ton pick-up truck. I built a high box on it to hold our stuff, such as an old fridge and washer, my harmonium and a home-made bed, table, chairs, bookcase etc. One week later we drove through the U.S. to Manitoba.

On Sunday, May 3,1959, we were married in Carman at the end of the regular church service by the Rev. J. Mulder, his first wedding in Canada. Annie had made her own wedding dress and with my dry-cleaned suit, we really looked the part. There were no gifts, no shower and no reception. A family dinner at home included our neighbours, Roy and Maybel as well as the pastor and his wife. We had the date of our wedding engraved in the plain wedding bands, which we had bought for our engagement a year earlier for five and seven dollars each. On Monday we went to the photographer. These were our only expenses, less than $10, and the marriage is now in its 48th year. Oops, there was one important gift, a piglet. After seeing the photographer, we went all dressed up to a hog farm where we had been invited for coffee. They took us into the barn where we could pick our present from several litters. On the way home, Annie had to hold the wiggly piglet in an open box on her lap while wearing her wedding dress. We called our boar Felix and he served us and 10 sows quite well in the next four years.

The old farm buildings were all in need of repair. They had not been used for years. We had no money for equipment and seed. We only had an old tractor, worn-down harrows and a plow. The Dutch Credit Union, made up of fellow church members, was operated by a member who had recently moved to Winnipeg. He could not consider giving two coalminers a farm loan, he said. However, with a personal bank loan and credit from a co-op store and a seed plant, we got started. Annie’s income from housekeeping at three places was enough for us to live on for the first year and to set up our personal household. In winter I worked from 3 am to 6 am, scraping pelts of mink for some extra income. Four years later, we had all the equipment necessary to operate a half section or a 320 acre farm with 12 milk cows, 10 sows, laying hens, hogs, feeder cattle and contracts for growing sugar beets, peas and cucumbers. Only two annual payments were outstanding on a 3-ton truck and a self-propelled combine.

In August 1963, it became clear that our farm would never become mine unless I bought it for the going price, which was more than twice the purchase price. For the four years of my part in this endeavour, I could deduct labour wages of $2200 per year minus the cash we had received so far (under $2000). I had a better income five years earlier. Moreover, I would never care for anybody’s stinking pigs. When the pigs are my own, however, they smell good and the long hours of hard work are a pleasure. So I dropped my milk pail next to the cream separator and drove to Winnipeg. There I bought airplane tickets for my wife and four children, ages 3, 2, 1, and three weeks. I also rented a U-Haul trailer. We went back to friends in the Fraser Valley at the west coast. There we started all over. In the previous three years Annie had managed the family on $10 a week plus farm products. Therefore, we knew how to get by on very little. (My four years, I reasoned later, were no loss, because they secured the care of my aging parents. That would have been my responsibility anyway and could have been a great burden).

Working with Harry, our contracts in digging ditches and making sewer connections to homes, was hard work, but it paid well. After about three months, we bought a home on half an acre in Surrey near the freeway (10555-160 Street). Eventually I delivered eggs and poultry again. Annie substituted our income by caring for foster babies, two at a time. With our own children, she had four in diapers, the washable kind. The babies arrived directly from hospital at seven to ten days old. They were usually adopted in about three or four months and immediately replaced. In those days, teenage mothers were encouraged to give them up for their own benefit. It paid $100 per month. Annie always saved us money by baking bread, canning food, sewing all our clothes and by making shrewd purchases. The Bible describes her quite well at the end of Proverbs 31. Rather than considering what we would want, we were always appreciating what we were able to have. For a while, I subcontracted the installation of electric dryer cables in new homes on my days off. It was a heavy job electricians avoided.

In November 1965, I signed up with the Correctional Service of Canada, because egg delivery was a dead-end job. The new job paid a little less, but a life-long career seemed more than likely. I had been told that the duties of a ‘correctional officer’, at the newly constructed treatment center for drug addicts in Abbotsford, would be to assist instructors. They taught several trades to groups of ‘patients’ who used expensive equipment and machinery. The possibility of taking courses and becoming an instructor myself interested me the most. But during a nine-week orientation course, I realized that I was to be a common prison guard and that the centre or ‘hospital’ was a modern jail. Therefore, I decided to quit, but only in the spring at the end of the course. A few days later, however, I learned that new penitentiaries were also going to employ counselors, guidance officers and therapists. So I concluded to give it two years.

By studying several books on penology, rehabilitation and therapeutic methods, I was soon involved in that aspect of prison-work. I learned a lot when a therapist called in sick and I was to lead an odd group-therapy session. I learned the most when I was appointed to temporarily take charge of the reception wing for several months. This involved interviewing new-comers, assessing them and making recommendations with respect to their placement in a job and a mandatory therapy group. In the fall of 1966, we had sold our home and rented a place in the Abbotsford area close to the institution.

In August 1968, right after we had bought an expensive home in town, two colleagues and I were transferred to Winnipeg as ‘counselors’. With two others and a director, we were to set up a ‘pre-release’ center downtown for about 20 residents. (Again my family had to move. When we bought a home a few months later in Winnipeg, our fifth child celebrated his first birthday at his fourth address). Our annual salary jumped from $6000 to $9000. As counselors, we selected inmates from the penitentiary, housed them downtown and helped them to secure jobs and look after themselves with respect to food and clothing. During the last three or four months of their prison term, we provided supervision and guidance in re-establishing themselves in society and with their family. This set-up became the model of half-way homes and the foundation of day-parole legislation. With some guidance from our senior counselor, a licensed psychologist, we took correspondence courses from McMaster’s University. In April 1973, our five credits earned us Certificate in Corrections. In the church community I functioned as an organist on a harmonium and as an elder. Moreover, I also coordinated a bible-study publication distributed across Canada for nine years. My wife Annie always made sure that I was never interrupted in my studies or work. Shift work, in covering the pre-release center 24/7, was rather detrimental to family life. For a few years we again had several foster children, but now between the ages of 2 and 4.

In the fall of 1973 I was given a miraculous opportunity to complete a BA degree. Instead of the usual 50% to 75% salary allowance for educational leave, I was now offered 100%. So I attended the University of Winnipeg. In the fall of 1974 my education was interrupted for one month. The churches delegated me to be a member of a National Synod in Toronto. In spite of my absence during November, I still managed to get a B+ average in all my courses. In 1975 I graduated, majoring in psychology and sociology. This fully qualified me to be a Parole Officer. In 1979, a transfer to the Winnipeg parole office meant the end of shift work.

In the 1980’s, I completed a three-year Certificate Program of five courses in Public Sector Management. This allowed me to skip the repetitive seminars we had to attend. Over the years, they had become too boring. As a hobby, I also wrote and published organ music, such as hymn harmonisations, tune variations and organ offertories, just because I thought I could.

In December 1995 and after 30 years of service, I submitted my letter of resignation, stating that I was looking forward to the next thirty years of my life. The Dutch military draft had declared me ‘unfit for the military’ at age 19. (Apparently a bone-marrow infection at age fifteen had made me too risky a candidate for the draft). I now retired after having used only 25 of the 450 sick-days earned in 30 years. This was an obvious blessing and a pretty good record.

My jobs with the Correctional Service were always interesting and challenging. There never was a dull moment, for I would read or study during unproductive times. At the same time, I managed to ward off derogatory aspects of the job. A few colleagues were not so lucky. Some suffered from burn-out within ten years, while others acquired negative attitudes and lifestyles. Moreover, as a parole officer, I could practically do the job as I saw fit. Parolees generally accepted and respected my advice and strict demands, because they claimed that I was also straight forward and fair. Canada gave me opportunities to exercise my full potential and to be who I was. They were true blessings in my life.

Without a definite career goal, I worked hard at whatever was put in front of me. I always tried to make the most of every opportunity that presented itself with the motto, to do today what could be put off until tomorrow. I just wanted to live a life of self-reliance and independence but in full dependence on God, subject to His will and so face up to the consequences of my actions. The Dutch culture did not allow me to have that. It provided care from the cradle to the grave, which I viewed as the life of a slave. To have a coalminer end up as a civil servant in the Dutch department of justice was impossible. This was confirmed when that department gave me a tour of Dutch prisons in 1972. I always rejected the herd mentality of conformity. This seemed to be disturbing to a lot of people who expect everyone to occupy and enjoy their own, prescribed niche in society. Canada allowed me to just be myself. Where else could a coalminer earn a successful living and improve himself while being employed as a labourer, a junior draftsman, a ditch digger, a salesman electrician helper, a farmer, a guard, a counselor or a parole officer?

I always refused to just ‘do time’ or punch a clock. I even convinced a few prisoners to do the same and turn their term to their profit. I still loath competition or attempts to appear better than others or make more money. My chief motivator beside curiosity is to always be self-critical and to do better today than yesterday. Striving to outshine others, in fact or appearance, promotes jealousy, manipulations, haughtiness or defeatism. Completing what you start to the best of your ability, like running a marathon, is more valuable to me than being the first, second or third. To compete often means to divide or separate while to cooperate is to unify or strengthen. Winners may praise competition, but most others seem not to dare to disagree. Those who do not win, may feel degraded and may tend to live like failures. As a teen I saw myself being forcefully coached into that direction. I just refused to play those games. At age 17, I consciously decided to never let others decide how I should feel about myself. So I ignored or opposed their social and often veiled intimidations, innuendos or shunning. It served me well, I think, for without any concern or interest in popularity or riches, I could grow in faith, skills and confidence. Canada offered many open doors, which did not exist in the old country.

At this time, spring 2006, I have enjoyed my retirement for ten years in the company of my wife. We stay actively involved in hobbies, studies, music, physical and social activities. Daily walks in winter and 20 km bike rides in summer are part of the ‘work’ program. Every five years or so, we visit my wife’s relatives overseas. But we are in the Netherlands as tourists, because from the day we arrived here, Canada is ‘home sweet home’. Our vacation trips are mostly in Canada as far as Vancouver Island, Yellowknife or Cape Breton Island. Last year we visited Pier 21 on my 50th anniversary as landed immigrant. With our six children, 27 grand-children and three great-grand children, we say, Thank you Canada, our home and native land.