by Steve Schwinghamer, Historian

(Updated July 20, 2021)

“I am not sure whether it will interest you or not but I may state that a number of coloured people have been going from your district lately to Western Canada, and it is not considered that they are a class of colonists who will be likely to do well in our country.” - Canadian Superintendent of Immigration W.D. Scott to P.H. York, 17 October 1910.[1]

Introduction: Policies of Exclusion for “Undesirable” Immigrants and Discrimination against Black Americans

Canada’s early twentieth-century immigration policies deliberately excluded groups thought unsuited for integration.[2] Beyond ordinary screening overseas, Canadian officials often took extraordinary steps to prevent these “undesirable” immigrants from traveling to Canada. These included rigorous screening overseas, the head tax, and even diplomatic agreements to limit emigration from other countries.[3] However, Canadian authorities encountered circumstances in which identifying undesirable immigrants as such was politically difficult. For example, British subjects from India or the West Indies could claim privileged legal status in Canada, despite being likely targets for exclusion based on “race.” Canadian authorities responded with indirect restrictions in these cases, requiring immigrants from these places to have more money in their possession, or make a continuous journey from their country of origin to Canada.[4] Between indirect policies and screening measures, Canada’s authorities developed a robust regime of preventative exclusion. However, their efforts to forestall Black immigrants from the United States went well beyond these other examples. Canadian immigration officials used their authority to obstruct Black American applicants for immigration to Canada in the early twentieth century through the selective enforcement of regulations, deception, bribery, and other questionable methods.

Black Americans faced renewed discrimination in the United States in the early twentieth century. Settlers from Oklahoma arriving in Canada in 1911 complained of disenfranchisement, theft of property, and refusal of admission to public places. One remarked that he had “… heard about the free lands here and also that everyone had the right to vote and was a free man.”[5] These factors all fostered interest in immigration to Canada, starting in 1907. Despite the pressures to leave and strongly expressed interest, only about 1000 Black Americans came to Canada between 1905 and 1912. These were years in which hundreds of thousands of Americans came to Canada, and this period was part of the overall historical peak period of Canadian immigration. What prevented Black Americans' participation in this massive migration?

Canadian Public Responses to Black Immigration

One of the key factors in the exclusion of Black Americans was Canadian domestic pressure. Many Canadian civic organizations wrote to government officials, demanding a ban on Black immigration.[6] The Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire (IODE) in Alberta called an emergency meeting to draft a letter on the topic, stating:

“We view with alarm the continuous and rapid influx of Negro settlers… this immigration will have the immediate effect of the discouraging white settlement in the vicinity of the Negro farms and will depreciate the value of all holdings within such areas.”[7]

Public debate often included a fear that the racial conflicts flaring in the United States would extend to Canada in the event of large-scale black immigration. Edmonton Municipal Council circulated a petition that gathered thousands of signatures, affirming “[i]t is a matter of common knowledge that it has been proved in the United States that negroes and whites cannot live in proximity without occurrence of revolting lawlessness, and the development of bitter race hatred…”[8] C.A. Speers, tasked to report on “negro colonies” in Canada for the immigration department, commented on the “peculiar prejudice of our Canadian and Anglo-Saxon people that…want this to be retained as a white man’s country.”[9] Despite sympathetic findings for Black immigrants in his report, Speers concluded:

“…in my many years of experience with the Department, I have endeavoured to be just and accord to all people a justice for their virtues. I do not impeach [African Americans] with any lack of industrious habit nor would I impugn their honesty of purpose, but… I would consider it unwise to permit them to come in large numbers to our country, as they would soon assume such proportions that we might be confronted with the same difficulties, political and social, as the American Republic is dealing with to-day.”[10]

Campaign of Dissuasion by Immigration Officials

The racist attitudes present in Canada’s turn-of-the-century public were reflected by immigration officials. One important barrier raised by Canadian immigration authorities against African-Americans was passive but deliberate: they refused to respond to Black people requesting assistance or information. The Canadian government agent in Kansas City noted that he had “refused [Black applicants] literature by mail. Instead of securing their removal to Canada I have stood in the way, or there would have been not only a few hundred but many thousands of them.”[11] Form letters mentioning the poor conditions in Canada for Black settlers were sent in response to inquiries from Black American community leaders, who were asked to share the bad news “among those who contemplate coming to Canada.”[12] The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) took note of the apparent colour bar and objected. In response, Frederick C. Blair (secretary in the department of immigration) wrote on behalf of the superintendent that “the climate and other conditions of this country are not such as would be found congenial to coloured people.”[13]

Canadian authorities also paid agents in the United States to warn Black Americans of the pernicious nature of Canada and to instruct them on its dangers. One such agent was G.W. Miller of Chicago, a Black American doctor, who wrote a convincing if contrived editorial for the Oklahoma Guide, a newspaper with primarily Black readership published in Guthrie, Oklahoma. Among other discouraging fancies, he wrote of the Canadian border that “your wife and daughter are stripped of their clothes before your very eyes and examined by a board of men.”[14] Miller held public meetings in Oklahoma communities over the summer of 1911. This had the desired effect, with Miller reporting that the poor reputation of Canada had spread throughout the state by the end of his work, in July 1911. Not coincidentally, demand for immigration to Canada plummeted.[15]

(See an example of Miller’s writing at http://gateway.okhistory.org/ark:/67531/metadc96112/m1/1/)

Administrative Barriers to Black Immigration

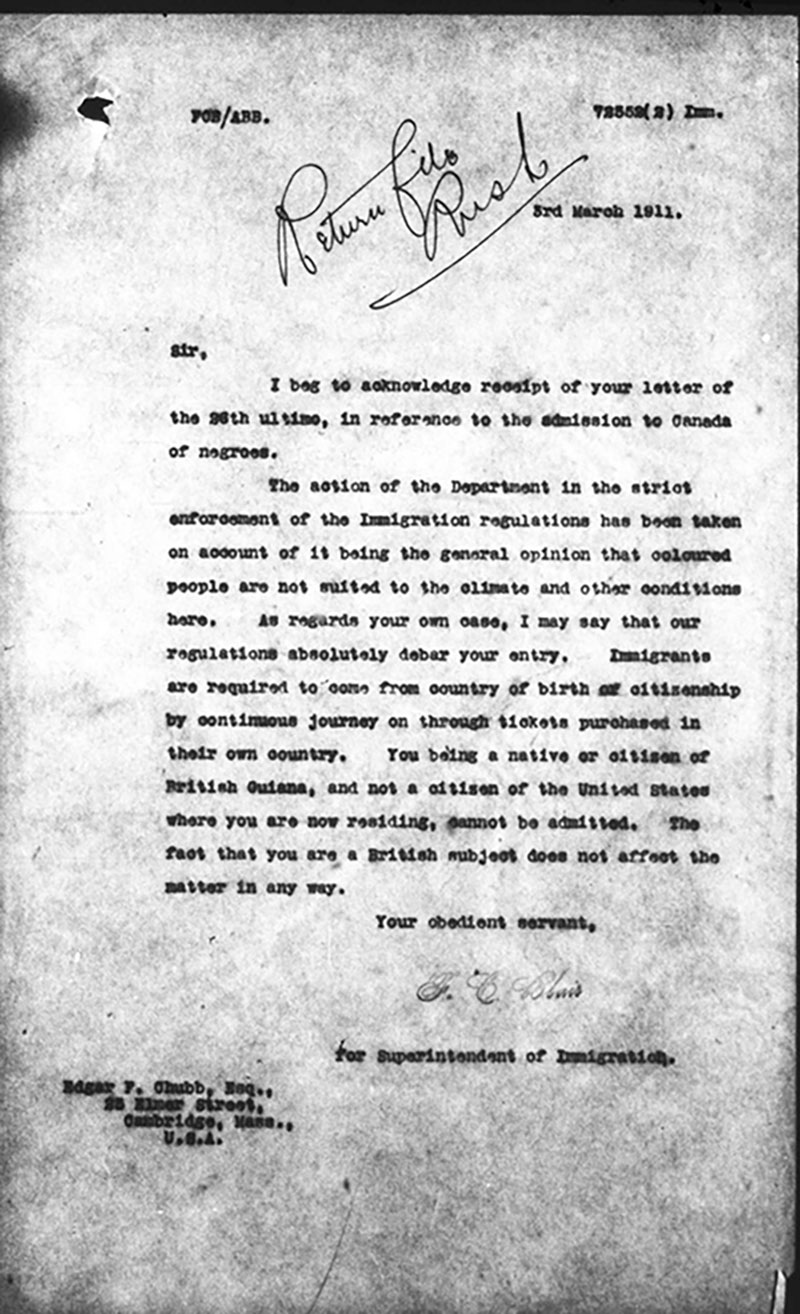

Along with this anticipatory form of exclusion, immigration authorities arranged other barriers. Immigration agents refused Black Americans certificates verifying their status as bona fide farmers. Railway representatives were instructed to ensure that they pay a full fare, rather than the reduced settler rate – unless they could produce the certificate immigration agents were forbidden to give them.[16] A medical examiner was offered bribes for each Black settler he turned away.[17] Blair invoked that reliable tool for Canadian racial exclusion, the continuous journey regulation, to refuse a Black man born in British Guiana who was living in the United States and wished to come to Canada.[18]

Credit: Library and Archives Canada RG 76 Volume 192 File 72552 Part 2

A Trinidadian doctor, practicing in the United States but a British subject by birth (and a veteran of the Royal Navy) was turned away by correspondence, based on his climatic unsuitability.[19] Officials even discussed enlisting Booker T. Washington, a prominent African American educator and advocate, to redirect the interest of Black Americans away from Canada and to remaining in the South.[20] In sum, even a modest scale of Black settlement triggered a sweeping response from Canadian authorities, within and outside ordinary departmental means for admission and control.

Conclusion: Banning Black Immigration

The episode closes with a definitive act: on 12 August 1911, the Canadian Government passed an Order-in-Council banning “any immigrants belonging to the Negro race, which is deemed unsuitable to the climate and requirements of Canada.”[21] The regulation was repealed but it expressed the public and political desire to prevent Black settlement in Canada that guided policy until after the Second World War.

Why did the department follow public and internal prejudice and enforce this racial exclusion? Speers addressed this in his report:

“… no matter how we may deplore this condition of affairs, [it] positively exists and general sentiment is directly opposed to large numbers of colored people settling throughout the west.

“Should the advent of a few colored people into Canada militate strongly against our American immigration then it would become serious…It would be unwise to retard the prospective advent of 200,000 good white people on account of the admission of a limited number of colored people. In addition to this, the sentiment is so strong throughout the districts in which these people are settling that I am obliged to appreciate and recognize public opinion and make the recommendation that this work of bringing in numbers of colored people be intercepted by such prohibitory means as the wisdom of the Department may deem expedient.”[22]

Those prohibitory means included remarkable efforts to discourage Black Americans at their points of origin, even before they undertook a journey to the border. Canadian immigration officials selectively enforced immigration regulations and used deceptions, fees, bribery, and other irregular methods to prevent Black settlement in Canada in the early twentieth century.

- Form letter repeatedly prepared by Laval Fortier and others for use above the signature of W.D. Scott. Many examples from 1910-1911 exist in Department of Immigration, “Immigration of Negroes from the United States to Western Canada”, Library and Archives Canada, RG 76 Volumes 192-193, File 72552 (hereafter File 72552). The referenced example was W.D. Scott to P.H. York, Ottawa, 17 October 1910, File 72552 Pt 2.↩

- K. Tony Hollihan, “’A brake upon the wheel’: Frank Oliver and the Creation of the Immigration Act of 1906”, Past Imperfect, 1 (1992), 100-101.↩

- Patricia E. Roy, A White Man’s Province: British Columbia Politicians and Chinese and Japanese Immigrants, 1858-1914 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1989), 207-213.↩

- For an example of a case of immigrants from India that touches both the East and West Coast of Canada, see W.R. Little to the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company, Ottawa, 9 May 1924, in Department of Immigration, “Immigration from British West Indies”, RG 76 Vol 567 File 810666 (hereafter File 810666), part 3.↩

- R. Bruce Shepard, “Diplomatic Racism: Canadian Government and Black Migration from Oklahoma, 1905-1912”, Great Plains Quarterly, 3:1 (1983) 6.↩

- This correspondence extends throughout Part 3 of File 72552↩

- IODE Alberta Chapters to F. Oliver, Edmonton, 31 March 1911, File 72552 Pt 3.↩

- Municipal Council of Edmonton to W. Laurier, Edmonton, 18 April 1911, File 72552 Pt 3.↩

- C.A. Speers to J.B. Walker, Winnipeg, 26 October 1910, File 72552 Pt 2, 4.↩

- C.A. Speers to J.B. Walker, Winnipeg, 26 October 1910, File 72552 Pt 2, 6.↩

- J.S. Crawford to F. Oliver, Winnipeg, 2 Dec 1910, File 72552 Pt 2.↩

- L.M. Fortier to Rev. A. Roberson, Ottawa, 7 March 1911, File 72552 Pt 4; F.C. Blair (on behalf of Scott) to Cory, Ottawa, 14 March 1911, File 72552 Pt 4.↩

- F.C. Blair to W.E.B. DuBois, Ottawa, 7 March 1911, File 72552 Pt 2.↩

- G.W. Miller, “On Western Canada and Conditions As He Found Them”, Oklahoma Guide (Guthrie), 6 July 1911, 1; accessed via http://gateway.okhistory.org/ark:/67531/metadc96112/m1/1/↩

- Shepard, “Diplomatic Racism”, 10-12.↩

- J.L. Doupe to W. Bannatyne, 30 December 1910, File 72552 Pt 2.↩

- Robin Winks, The Blacks In Canada: A History (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1997), 310.↩

- F.C. Blair to E.F. Chubb, Ottawa, 3 March 1911, File 72552 Pt 2.↩

- W.D. Scott to A.W. Thomas, Ottawa, 19 January 1911, File 72552 Pt 2.↩

- Shepard, “Diplomatic Racism”, 10.↩

- Barrington Walker, ed., The African-Canadian Legal Odyssey: Historical Essays (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012), 30, 45.↩

- C.A. Speers to J.B. Walker, Winnipeg, 26 October 1910, File 72552 Pt 2, 5.↩