by Jan Raska, PhD, Historian

(Updated October 20, 2020)

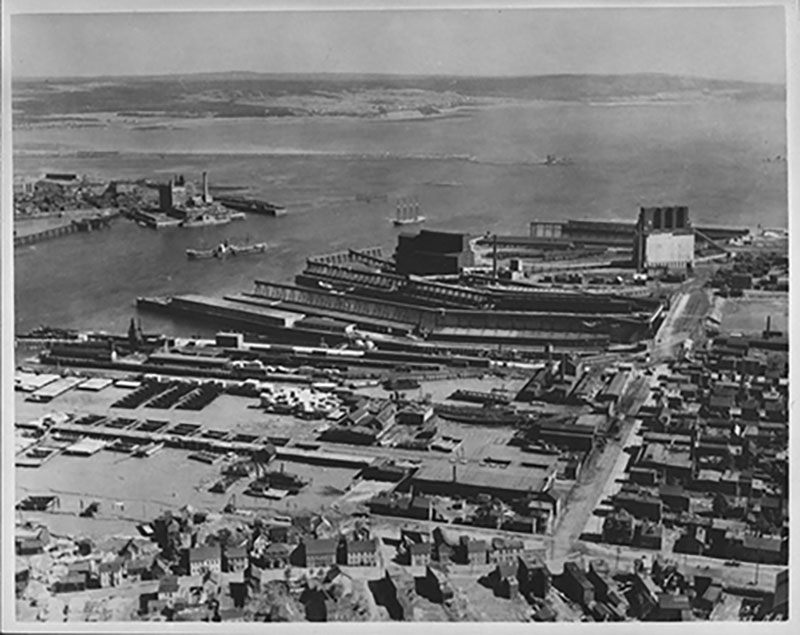

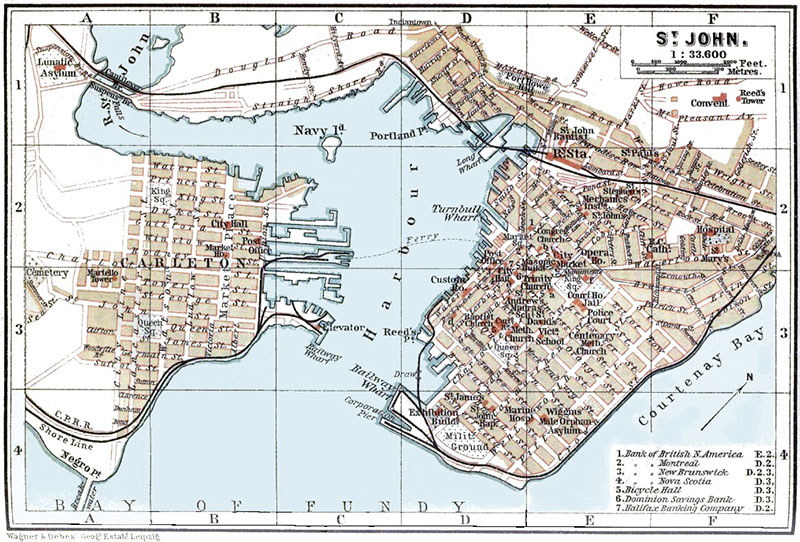

Introduction: Establishing a Port at the Mouth of the St. John River

Before the arrival of Europeans, the Wolastoqiyik (also known as Maliseet) were the primary inhabitants along the St. John River (known in Wolastoqiyik as Wolastoq) and the area later encompassing Saint John (Menahkwesk). In 1604, a French expedition sailed to the mouth of the Wolastoq River. As part of the Pierre Du Gua, Sieur de Monts expedition, Samuel de Champlain “discovered” the river and named it after the feast of St. John (24 June). This expedition is considered the source of the earliest written record about the Port of Saint John, the name the British gave to the river. The area was only sparsely populated by Acadians, New England Planters, English, Scottish, Irish, and German immigrants until the American Revolution. In 1775, Portland Point, at the mouth of the St. John River, only had about 140 inhabitants. In the 1780s, some 15,000 Loyalists from the United States were offered land and chose to resettle in the area that became New Brunswick in 1784. At one point, the Wolastoqiyik had ordered the British from the St. John River. In 1778, the two sides met to discuss grievances and reparations. A peace treaty was signed in 1778, along with the offer of a wampum belt and the promise to build a trading post along the river. In the early nineteenth century, lumber and shipping increased significantly due to demand throughout Great Britain. Saint John became the largest shipbuilding city in British North America (BNA) and the fourth largest in the British Empire. By the 1850s, a wharf was built at Reed’s Point (now a part of Lower Cove Terminal) for both local steam ferry service across the harbour and transatlantic steamship services. The emergence of steel-hulled shipbuilding – which replaced wooden ships – and the rise of westward expansion across BNA increased railway links while passenger travel brought people and trade to the city’s port area.

Credit: Canada. Dept. of Interior / Library and Archives Canada / PA-047926

Beginning in the latter-half of the nineteenth century, Saint John served as a strategic winter port for shipping interests in Montreal which could not navigate the sea ice found in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the St. Lawrence River. In 1889, the Canadian Pacific Railway established a line from Montreal to Saint John whereby most of its transatlantic shipping traffic was directed through the Port of Saint John during the winter months. From 1890 to 1896, Portland, Maine remained the terminus for the Grand Trunk Railway and moved Canadian freight. During this period, government officials and business interests sought to divert trade from American ports during the winter season to Saint John and Halifax. In 1895, the Canadian government decided to subsidize steamship traffic between British ports and Saint John in an effort to divert Canadian trade from ports in the United States.[1]

Situated at the mouth of the St. John River, the port was also a vital point of entry into Canada. As one of Canada’s national harbours, it is home to Partridge Island – previously one of the four major quarantine stations including William Head (BC), Grosse Ile (QC) and Lawlor’s Island (NS) found across the country. Opened in 1785, it is estimated that close to 3 million immigrants and mariners were processed through the site before its closure in 1941.[2] Nearly 2,000 immigrants were buried there, many of whom succumbed to cholera, smallpox and typhoid fever.[3] With the opening of the Saint John Airport in 1952 and the construction of the Saint Lawrence Seaway in 1959, the Port of Saint John witnessed a decline in transatlantic passenger traffic. By the 1960s, the continued use of icebreakers in the St. Lawrence Seaway, technological advances in aviation, and increasing popularity of air travel through the Saint John Airport diminished the port area’s role as a point of entry into Canada. The Port of Saint John maintained its strategic significance as a vital shipping link to the rest of Canada.[4]

Credit: Wagner & Debes, Leipzig

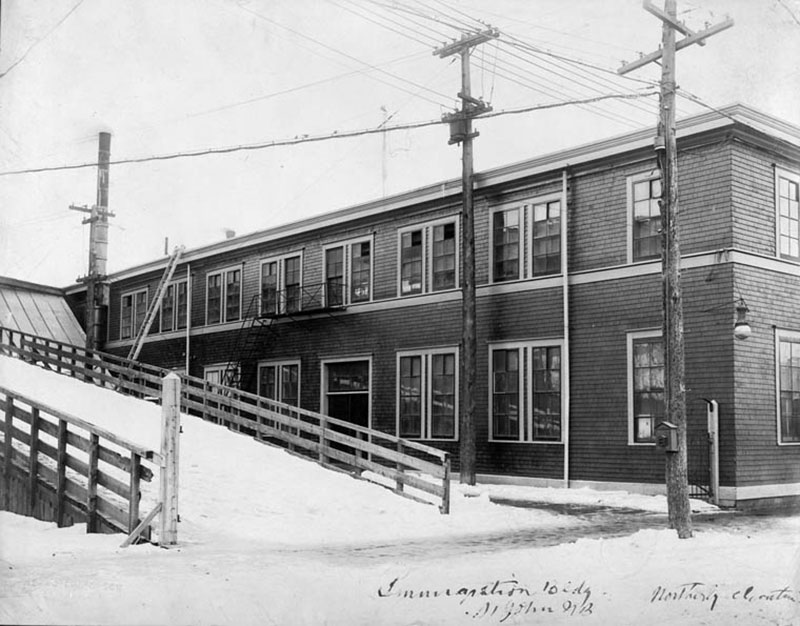

Credit: Library and Archives Canada / PA-020918

Credit: Canada. Dept. of Interior / Library and Archives Canada / PA-049781

Credit: Canada. Dept. of Interior / Library and Archives Canada / PA-049774

Immigration Facilities and Transatlantic Passenger Traffic at the Port of Saint John

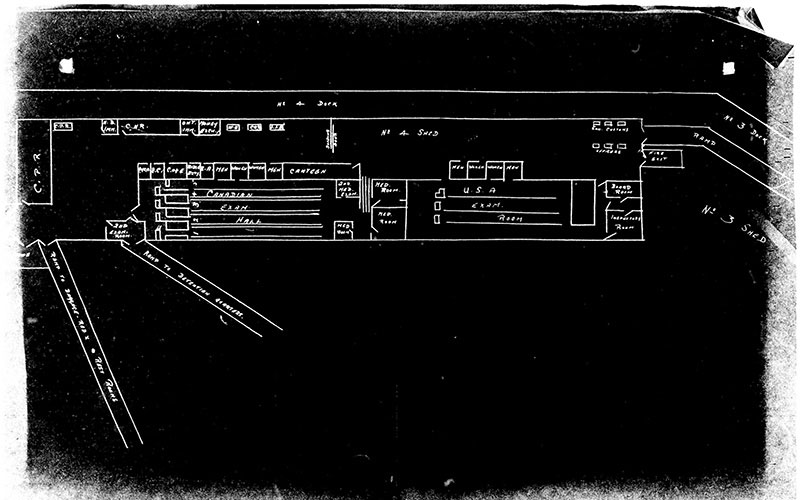

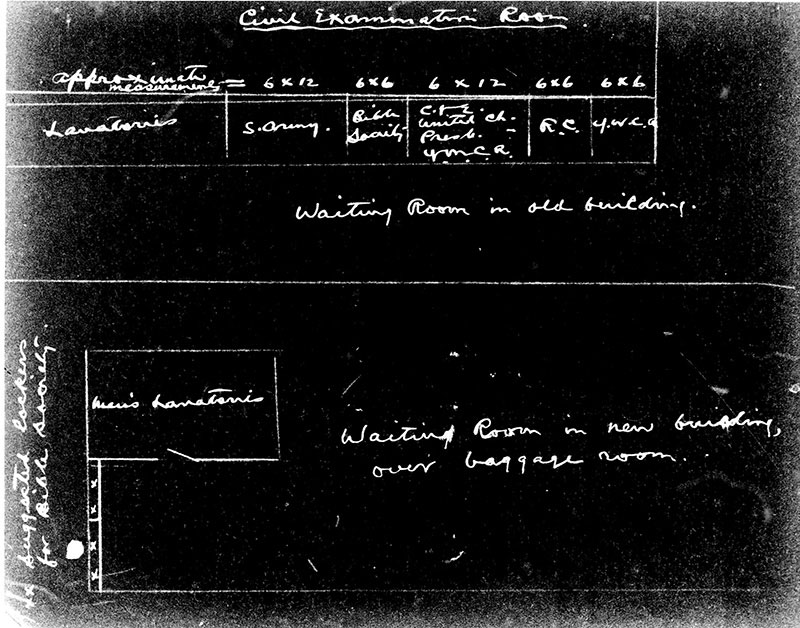

On 31 December 1904, the Department of Public Works entered into a lease with the City of Saint John for use of the warehouse (shed) and ramp at No. 4 wharf in West Saint John. The lease encompassed the second storey of the warehouse and was negotiated for a period of ten years. Since no renewal lease was negotiated in 1914, the Department of Immigration and Colonization’s tenancy became year-to-year.[5] The Canadian government owned the immigration building adjacent to the warehouse at No. 4 wharf and shared responsibility for its upkeep with the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR). The building housed civil and medical detention facilities. The second floor of the warehouse (shed) at No. 4 Wharf served as an immigration hall. A ramp connected the warehouse to the adjacent immigration building. There were separate ramps to the baggage area, rest rooms and the detention quarters in the immigration building, and to connect the warehouse with No. 4 and No. 5 wharfs. The immigration hall included various rooms allocated to CPR and Canadian National Railway (CNR) colonization agents, Canada Customs, Canadian and American immigration officials, and voluntary service agencies.[6]

During the interwar period, the immigration facilities maintained the sociocultural and political norms of the period that were also found at other ports in Montreal, Quebec, and Halifax. Recently-disembarked immigrants first proceeded toward medical examination, and then were processed by immigration officials before their personal effects were inspected by customs officers. Medical and detention facilities divided men and women, British and foreigner, into separate quarters. Precedence in processing was given to returning Canadians and first-class immigrants followed by those in steerage.

Immigration Building – Accommodations and Services

Credit: Isaac Erb & Son / Library and Archives Canada / C-045083

Facilities

- Baggage Room

- Board Room (located in Civil Detention Quarters)

- Catering Room

- Detention Quarters (bars on windows)

- Dining Room (on main floor of building)

- Dormitories, Men’s Dormitories – British and Foreign sections

- Dormitories, Women’s – British and Foreign sections

- Guard’s Room (on ground floor and used by the Senior Guard and Guards)

- Guard’s Store Room (added in mid-1920s and used by Senior Guard)

- Kitchen

- Lavatories

- Matron’s Quarters (also consisted of a kitchen, bathroom, dining room, sitting room, and hallway)

Credit: Public Works Dept. / Library and Archives Canada / PA-046591

Credit: Public Works Dept. / Library and Archives Canada / PA-046593

Credit: Public Works Dept. / Library and Archives Canada / PA-046592

Government Offices

- Accountant’s Office

- Guard’s Desk (outside of Civil Detention Quarters)

- Inspector’s Office

Warehouse (Shed) at No. 4 Wharf – Accommodations and Services

Facilities

- Canteen

- Immigration Examination Hall (two lines for medical inspection, later expanded to five lines upon doctors’ requests)

- Medical Examination Rooms (3)

- Men’s Lavatories (3)

- Ramp (connected inspection floor on the second floor of warehouse at No.4 wharf to civil and medical detention quarters in the immigration building)

- Women’s Lavatories (3)

Government and Railway Offices

- Canada Customs Offices (3)

- Dominion Immigration Agents Offices (3)

- Money Exchange Office

- New Brunswick Colonization Agent’s Office

- Ontario Colonization Agent’s Office

- Post Office

Non-Governmental Offices

- Canadian National Colonization Agent’s Office

- Canadian Pacific Colonization Agent’s Office

- Canadian Pacific Ticket Office

- Western Union Telegraph Company Office

Voluntary Service Agency Offices

- Baptists, Congregationalists, Methodists, and Presbyterians Office (latter three denominations merged together in 1925 to form the United Church)

- British and Foreign Bible Society in Canada and Newfoundland Office

- Church of England Office

- Jewish Immigrant Aid Society Office

- Roman Catholic Church Office

- Salvation Army Office

- YMCA Office

United States Immigration Service Offices

- Men’s Lavatory

- United States Board Room

- United States Inspector’s Office

- United States Medical Examination Rooms (2)

- Waiting Room (also consisted of an adjacent lavatory)

- Women’s Lavatory

Credit: Library and Archives Canada, Immigration Branch fonds, RG 76, vol. 667, file C1595, pt. 2

Credit: Library and Archives Canada, Immigration Branch fonds, RG 76, vol. 667, file C1595, pt. 2

Connected to the adjacent warehouse at No. 4 wharf by a ramp, the old immigration building held the civil and medical detention quarters, and office administration. During the winter season, heating was provided by steam from the nearby CPR elevator. The Civil/Medical Detention Quarters maintained barred windows and a separate dining room. The quarters were secured by immigration guards. The medical detention dining hall was used in the 1923-1924 winter season as a general dining area due to the state of the old dining hall on the main floor.[7]

Department of Immigration and Colonization Revamps the Dining Facilities

In November 1924, the Department of Immigration and Colonization decided that the Public Dining Room would be relocated back to the main floor. Sixty-five kitchen chairs and twenty-two tables were found to fill the room. A hanging sign informing travellers of a “Government Controlled Restaurant – Meals –” was suspended from the ceiling inside the main entrance of the building. The Staff Dining Room was located near the public dining room formerly used as a dining room for medical detentions. The aforementioned dining rooms would be served from the old kitchen on the ground floor. A Baggage Room was located on the ground floor.[8] In observing the processing of newcomers in the immigration building, Immigration officer Amy E. McKow, informed her supervisor that at Saint John, a passenger first purchased a meal ticket at the canteen counter. Then, he or she “must traverse the distance from the canteen to the dining-room, which is half the length of the main building, across the bridge to the next building, down the runway to the baggage-room, the whole length of the baggage-room, out-of-doors (no matter what the weather) up the outside runway to the kitchen, through the kitchen to the dining-room. This is hard enough upon men; for women and children it is almost impossible especially upon stormy days.”[9]

Outdated Immigration Facilities: Canadian Officials Advocate for Site Renovations and Further Infrastructure

Immigration and medical officials at Saint John attempted to streamline the immigration process and maintain health and safety by advocating for site renovations and further infrastructure. Due to the outdated facilities, Canadian immigration officials were often vulnerable to dangerous situations including fire since most of the port area’s buildings were wooden structures. On 14 March 1924, a fire was discovered shortly before 8:30am under the floor of the immigration building, directly beneath the medical quarters, facing Union Street. Due to early detection, the flames were extinguished by two firemen, Egan and Pickett.[10]

Throughout the 1920s, the Port of Saint John required additional funding. In 1927, the port was nationalized with federal authorities taking control of the site, partly in an effort to secure its financial situation. Two years later, increased funding permitted renovations to be completed and forty benches – similar to those used in Halifax – were purchased so that the newly enlarged hall could accommodate 500 individuals. The additional space permitted immigration officials to rapidly process immigrants, tourists, and returning Canadians including during the months of March and April when passenger traffic was heaviest.[11] Saint John’s expanded immigration facilities were soon devastated by the same dangerous hazard that occurred seven years earlier.

1931 Fire: Complete Destruction of Immigration Facilities and Surrounding Area

On 22 June 1931, a waterfront fire completely destroyed the immigration building and surrounding area in West Saint John. The fire broke out at No. 7 CPR dock. Immigration officials were able to save their files, but all other supplies, furniture, and equipment were burned.[12] Canadian officials estimated that the fire cost $10 million in damages. Reconstruction began in early July to establish new freight buildings at Piers 4 and 14, and to replace the facilities lost at Piers 5, 6, 7, 15, and 16. At the time, the Saint John Harbour Commission had not made any plans to accommodate the Department of Immigration and Colonization.[13] Eastern Division Commissioner of Immigration, J.S. Fraser, sent a letter to Mr. Schofield, Chairman of the local harbour commission indicating that the immigration facilities recently destroyed in the fire “compared very unfavourably with the facilities which have been provided at Halifax and Quebec…” Fraser went on to suggest that it would be proper to receive, examine, and house transatlantic passengers in one building as opposed to “a maze of buildings, which were heretofore used.”[14]

For the 1931-1932 winter travel season, the Saint John Harbour Commission made arrangements for inspectional facilities, but none for detention quarters. On behalf of the immigration department, Public Works rented a section of a former sanatorium owned by the Maritime Sanatorium Company for $3,700 per annum. The property, which was located at 90 Lancaster Avenue in the West End of the city, housed civil and medical detentions during that winter season. At the time, the former sanatorium was also being used as a temporary hospital by the city until the construction of its municipal hospital was complete.[15] To prevent another devastating fire from occurring in the future, the Canadian government rebuilt the wharves in concrete and steel rather than wood. With these changes, the port area was able to handle increasing traffic.[16]

Lacking Necessary Infrastructure: Diverting Ocean Liner Passenger Traffic to Halifax

In October 1931, Canadian Pacific Steamships (CP) entered into a ten-year agreement with CNR whereby their vessels destined for Saint John would also dock at Halifax. During the 1931-1932 winter season, CP only docked at Halifax because Saint John lacked the necessary infrastructure for passenger traffic. Canadian Pacific did not give advance warning to the Department of Immigration and Colonization or its officials in Saint John as to its intentions. Both CP and the CNR were to share in accommodating passenger travel and the movement of freight in the Maritimes. Although CP remained committed to making Saint John its winter port for passenger traffic, due to a lack of adequate facilities, Canadian immigration officials supported the examination of passengers aboard ship as was the practice at Quebec City.[17]

By the spring of 1932, Canadian immigration officials in Saint John were housed on the second floor of the Customs House (Board of Trade Building) previously vacated by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. The two rooms provided the local officials with enough privacy to conduct Boards of Inquiry for the removal of inadmissible immigrants.[18] A staff of five individuals – C.H. Maxwell, Inspector-in-Charge; J.B. Sibson, Inspector; Miss Boone, Clerk Stenographer; and two Guards – shared both rooms.[19]

Immigration and Public Works officials decided to allow the issue of rebuilding the immigration facilities at West Saint John to “remain in abeyance for a period of ten years” in order to see how the situation developed. Since the fire occurred during the Great Depression, federal officials were hesitant to quickly appropriate funding to rebuild the immigration facilities. However, the capacity to rebuild remained an option if all concerned parties agreed to move forward. In March 1938, Canadian immigration officials concluded that until CPR altered its present arrangement of examining passengers at Halifax during the winter season, no reconstruction of an immigration facility should occur at Saint John. During the 1930s, ships did berth at Saint John. In one case, SS Athenia of the Cunard White Star Line arrived during the winter season, and thirty to forty passengers were examined onboard the ship.[20]

Postwar Plans: Constructing a New Immigration and Customs Facility

In 1945, plans were compiled for a new immigration and customs facility. The EGM Company of Montreal was awarded a $1 million contract to begin clearing the site for construction. On 9 February 1948, work began in earnest at the docks in West Saint John. Construction lasted approximately two years. On 9 December 1950, the new immigration and customs building was officially opened with 300 recently arrived immigrants in attendance. The group of newcomers arrived on RMS Empress of Canada – the first ship to dock at the new facility. In the new terminal, immigrants were once again processed by immigration, medical, and customs officers as before. Immigrants reached the new facility by an enclosed ramp from sheds 9 and 10. Hand luggage was placed in special cages on the second floor which also served as an assembly hall and inspection floor as it had decades earlier. Newcomers were then sent to the doctors’ offices for medical examination. After this inspection was completed, passengers then headed to the section of the second floor reserved for immigration examination. The second storey of the new immigration and customs building also housed a fully-equipped kitchen, cafeteria-style dining hall, detention rooms for men and women, quarters for deportees, and detention cells for immigrants who awaited deportation.

Once immigrants were successfully processed and medically cleared, they headed downstairs to the ground floor for customs inspection and afterward to its general waiting area and baggage area. Tickets could be secured from the offices of the CPR, CNR, and other steamship companies. Immigrants departed from Saint John by special trains for their final destinations across Canada and the United States. A hospital existed on the third floor of the immigration building. The hospital consisted of four wards, a recreation room, emergency operating room, outdoor recreation area, a dispensary, and a total of twenty-five beds.[21]

1970s: Decline of Immigration through the Port of Saint John

In the 1970s, the port area received its last major upgrade to existing piers and infrastructure. With the increasing popularity of airline passenger travel and the emergence of airports as primary ports of entry, the immigration facilities at the Port of Saint John processed only 1,646 immigrants from overseas and 1,015 immigrants from the United States during the period 1966-1996.[22] In 1997, the immigration and customs building was demolished.[23] During the 2010s, port officials began to consider renovating existing facilities in order to prevent shipping container growth from stalling.[24] Today, Port Saint John, as it is now called, is one of nineteen major Canadian ports designated as a Canadian Port Authority (CPA) and remains vital to Canada’s domestic and international trade.

Conclusion: From the Rise of Shipping and Transportation Interests to the Decline of Ocean Liner Passenger Traffic through Saint John

In the latter-half of the nineteenth century, Saint John became a strategic “winter port” for Canadian shipping interests, as the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the St. Lawrence River became unnavigable due to ice. The CPR established a line from Saint John to Montreal – bypassing Quebec City – where transatlantic shipping could be directed during the winter season. In 1895, Canadian officials agreed to subsidize steamship traffic between British ports and Saint John in an effort to further dissuade business interests from shipping their goods through American ports, including the Grand Trunk Railway’s terminus at Portland, Maine.

Between 1785 and 1941, immigrants and mariners requiring medical examination were processed at North America’s first quarantine station, Partridge Island. In 1904, the Canadian government entered into a lease with the City of Saint John for the use of available facilities at the shipping docks in West Saint John. The lease encompassed the second storey of warehouse No. 4. The federal government owned the adjacent immigration building. By the First World War, responsibility for maintenance of the leased infrastructure was shared between the Department of Public Works and the CPR. During the interwar period, the immigration facilities maintained the sociocultural and political norms of the period that were also found at other ports in Montreal, Quebec, and Halifax. Immigrants were first medically examined, then processed by immigration officials before their personal effects were inspected by customs officers. Medical and detention facilities divided men and women, British and foreigner, into separate quarters. Precedence in processing was given to returning Canadians and first-class immigrants followed by those in steerage. In 1931, the Port of Saint John’s immigration facilities were devastated by a fire that destroyed the waterfront and its infrastructure. With an estimated $10 million in damages, Canadian officials postponed reconstruction of the site’s immigration facilities choosing to divert transatlantic passenger traffic to Pier 21 in Halifax.

Following the Second World War, plans were established to rebuild an immigration and customs building previously located at the docks in West Saint John. In December 1950, the new facility opened to welcome recently arrived European Displaced Persons, political refugees, and returning Canadians. Beginning in the 1950s, the immigration facilities at the Port of Saint John witnessed a decline in transatlantic passenger traffic due to advances in aviation and the increasing popularity of air travel. For steamship companies, the bulk of their business rested with larger ports including Montreal, Quebec, and Halifax. The opening of the Saint John Airport in 1952 and the construction of the Saint Lawrence Seaway in 1959 also diminished the number of immigrant arrivals through the immigration facilities at Saint John. By the 1960s, technological advances in aviation, the continued use of icebreakers in the St. Lawrence Seaway, and the emergence of the city airport helped to diminish the port area’s role as a vital point of entry into Canada. As a national harbour, the Port of Saint John maintains its strategic significance as a vital shipping link to the rest of Canada.

- James H. Marsh, “Saint John River,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, last edited 4 March 2015, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/saint-john-river; Emily Burton, “The Alcohol Paradox: Consumption, Regulation, and Public Houses in Three Maritime Colonies of Northeastern British America, 1749-1830” (PhD diss., Dalhousie University, 2015), 237; John G. Reid, “Empire, the Maritime Colonies, and the Supplanting of Mi’kma’ki/Wulstukwik, 1780-1820,” Acadiensis 38.2 (Summer/Autumn 2009): 85; “History,” Port Saint John, http://www.sjport.com/community-inclusion/education/history/; Greg Marquis, “Celebrating Champlain in the Loyalist City: Saint John, 1904-10,” Acadiensis 33.2 (Spring 2004): 27-43; Charles N. Forward, “The Development of Canada’s Five Leading National Ports,” Urban History Review 10.3 (February 1982), 29; James Hannay, History of New Brunswick, Volume 2 (Saint John: John A. Bowes, 1909), 358-359; George W. Schuyler, Saint John: Scenes from a Popular History (Halifax: Petheric Press, 1984), 60-61.↩

- Harold E. Wright, L’Île Partridge Island: A Gateway to North America (Saint John: Harold E. Wright, 1995), 42. For an overview of Partridge Island, see also C.P. Brown, “The Quarantine Service in Canada,” Canadian Journal of Public Health 46.11 (November 1955): 449-453.↩

- “Marge George, “Irish Roots Grow Deep in Seaport of Saint John,” Toronto Star, 20 July 1991, J.15.↩

- For a historical overview of the Port of Saint John, see Robert H. Babcock, “Saint John Longshoremen during the Rise of Canada’s Winter Port, 1895-1922,” Labour/Le Travail 25 (Spring 1990): 15-46; Judith Fingard, “The Decline of the Sailor as a Ship Labourer in 19th Century Timber Ports,” Labour/Le travail 2 (1977): 35-53; Judith Fingard, Jack in Port: Sailortowns of Eastern Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1982); Forward, “The Development of Canada’s Five Leading National Ports,” 25-45; Marquis, “Celebrating Champlain in the Loyalist City,” 27-43; Greg Marquis, Saint John as an Immigrant City, 1851-1951 (Halifax: Atlantic Metropolis Centre, 2009); Greg Marquis, “The Ports of Halifax and Saint John and the American Civil War,” The Northern Mariner/Le Marin du nord, 8.1 (January 1998): 1-19; Elizabeth McGahan, The Port of Saint John: Volume One,…From Confederation to Nationalization (Saint John: National Harbours Board, 1982); Keith Mercer, “Northern Exposure: Resistance to Naval Impressment in British North America, 1775-1815,” Canadian Historical Review 91.2 (June 2010): 199-232; George W. Schuyler, Saint John: Scenes from a Popular History (Halifax: Petheric Press, 1984).↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, volume 666, file C1595, pt.1 “Immigration Building at Saint John, N.B.,” letter from R.C. Wright, Chief Architect, Department of Public Works, to W.J. Black, Deputy Minister, Department of Immigration and Colonization, 23 June 1923.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 666, file C1595, pt.1 “Immigration Building at Saint John, N.B.,” letter from Gerry G. Congdon, Travelling Inspector to J.S. Fraser, Division Commissioner, 8 September 1924.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 666, file C1595, pt.1 “Immigration Building at Saint John, N.B.,” letter from Gerry G. Congdon, Travelling Inspector to J.S. Fraser, Division Commissioner, 27 October 1924.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 666, file C1595, pt.1 “Immigration Building at Saint John, N.B.,” letter from Gerry G. Congdon, Travelling Inspector to J.S. Fraser, Division Commissioner, 19 November 1924.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 666, file C1595, pt.1 “Immigration Building at Saint John, N.B.,” letter from Amy E. McKow, Immigration Officer, to M.V. Burnham, Supervisor, Women’s Division, 12 April 1923.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 666, file C1595, pt.1 “Immigration Building at Saint John, N.B.,” letter from J.V. Lantalum, Dominion Immigration Agent, to M.V. Burnham, Supervisor, Women’s Division, 12 April 1923.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 666, file C1595, pt.1 “Immigration Building at Saint John, N.B.,” memorandum from J.S. Fraser, Division Commissioner to Arthur Leigh Jolliffe, Immigration Commissioner, Department of Immigration and Colonization, 11 February 1929.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 666, file C1595, pt.1 “Immigration Building at Saint John, N.B.,” letter from C.H. Maxwell, Dominion Immigration Agent to J.S. Fraser, Division Commissioner, Department of Immigration and Colonization, 22 June 1931.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 666, file C1595, pt.1 “Immigration Building at Saint John, N.B.,” letter from C.H. Maxwell, Dominion Immigration Agent to J.S. Fraser, Division Commissioner, Department of Immigration and Colonization, 15 July 1931.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 666, file C1595, pt.1 “Immigration Building at Saint John, N.B.,” letter from J.S. Fraser, Division Commissioner, Department of Immigration and Colonization to Mr. Schofield, Chairman, Saint John Harbour Commission, 27 July 1931.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 666, file C1595, pt.1 “Immigration Building at Saint John, N.B.,” letter from unknown to J.B. Hunter, Deputy Minister, Department of Public Works, 14 September 1931.↩

- i Port Saint John, “History,” http://www.sjport.com/community-inclusion/education/history/.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 666, file C1595, pt.1 “Immigration Building at Saint John, N.B.,” article “Two Railways to Co-operate in Maritimes: Will Work Together on Atlantic Traffic,” Montreal Gazette, 21 October 1931.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 666, file C1595, pt.1 “Immigration Building at Saint John, N.B.,” letter from C.H. Maxwell, Inspector-in-Charge to J.S. Fraser, Division Commissioner, Department of Public Works, Ottawa, 4 May 1932.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 666, file C1595, pt.1 “Immigration Building at Saint John, N.B.,” memorandum from Assistant Commissioner to Arthur Leigh Jolliffe, Immigration Commissioner, Department of Immigration and Colonization, 11 January 1933.↩

- LAC, IB fonds, RG 76, vol. 666, file C1595, pt.1 “Immigration Building at Saint John, N.B.,” memorandum from Gerry G. Congdon, District Superintendent to Arthur Leigh Jolliffe, Immigration Commissioner, Immigration Branch, Department of Mines and Resources, Ottawa, 11 March 1938.↩

- Harold E. Wright and Deborah Stilwell, Homeport: Campobello – Saint John – St. Martins, 1780-2000 (Halifax Nimbus Publishing, 2002), 150.↩

- Canada, Department of Citizenship and Immigration, Immigration Statistics, 1966 to 1996. http://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/202/301/immigration_statistics-ef/index.html. For each year, see “Total Arrivals in Canada by Port of Entry.”↩

- Wright and Stilwell, Homeport, 150.↩

- “Major Expansion, Upgrade in the Works for Port of Saint John,” CTV Atlantic, 13 January 2015, http://atlantic.ctvnews.ca/major-expansion-upgrade-in-the-works-for-port-of-saint-john-1.2186236.↩