by Jan Raska, PhD, Historian

(Updated June 22, 2022)

Introduction: Canadian Immigration before the Arrival of War Brides and Their Children

From 1945 to 1947, Canada’s immigration controls remained restrictive. Although a majority of labour organizations opposed the liberalization of immigration policy and the opening of Canada’s gates to immigrants, proponents of big business and humanitarian organizations supported a more generous immigration policy which would respond to the plight of Europe’s displaced population after the Second World War. A provision existed in the 1910 Immigration Act that allowed for the admission to Canada of bona fide agriculturalists who had sufficient means to commence farming in Canada. However, immigration remained prohibitive as Order-in-Council P.C. 695 of March 1931 only permitted agriculturalists and immigrants from the United Kingdom, United States, Ireland, Newfoundland, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa with “sufficient means to maintain themselves” to enter Canada.[1] Canada could have been the “land of hope and promise” for Europe’s displaced peoples. However Canadian immigration regulations also barred most European political refugees – individuals who fled fascist or communist totalitarian regimes in their homelands since the beginning of the war – from entering Canada in the first two years after the war. The federal government justified its inflexibility towards an increase in postwar immigration by claiming that there was a lack of “suitable” passenger vessels to transport individuals from Europe to Canada.[2] In many cases, military transports were prioritized to bring overseas Canadian servicemen and their dependents back to Canada.

Before the Canadian government amended its immigration policy to provide a humanitarian response to the European displaced person and political refugee crisis, it focused its attention on the resettlement of soldiers’ dependents. The resettlement of war brides and their children from 1942 to 1948 marked the first time that the federal government provided a “home to home service.” This movement of newcomers was considered of “very fine stock” and predominantly came from the smaller centres of the British Isles and the European continent to their new homes in Canada. In promoting and exemplifying prevailing ethnoracial attitudes about immigrant desirability and admissibility, Ottawa considered the war brides and their children – in particular those of British origin – to be “far above average in health and mentality.”[3]

Origins of Canada’s Repatriation of War Brides and Their Children

In 1941, Canada’s High Commissioner to London, Vincent Massey, recommended to officials within the Department of External Affairs that empty troop ships returning to Canada should also transport war brides and their children. Massey suggested that each adult passenger would pay fifteen dollars to provide for their own meals, while the Canadian government would charter the ships and pay for each traveller’s passage.

Six months later, the first Canadian servicemen discharged on medical grounds returned to Canada; they had married while serving in Britain, bringing this pressing issue to Canadian shores. The issue was put forth to the Immigration Branch who advised that “certain problems” would have to be overcome before war brides and their children could be permitted to enter Canada. The problems were divided into four points: a) finding satisfactory accommodation upon their arrival; b) the necessity of adequate assistance should they arrive before their husbands; c) possible marital discord, which would cause these dependents to become a public charge; and d) dependents who were physically, mentally, or morally unfit.

Canadian Military Headquarters also weighed in by objecting to the free repatriation of the war brides and children on the grounds that there were “too many irresponsible marriages taking place” in the United Kingdom. Military officials did not want to weaken regulations which forced servicemen to acquire permission to marry and then be placed under review. In early January 1942, the War Committee of the federal Cabinet agreed that Ottawa “should provide single minimum cost transportation, ocean and rail, to Canada for the wives and children of the members of the Canadian Forces overseas, where such personnel had returned or were returning to Canada.”[4] The same provision would be made for widows and children of Canadian servicemen who died abroad. Initially, the Department of Mines and Resources’ Immigration Branch was responsible for bringing war brides and their children to Canada. In August 1944, Order-in-Council P.C. 6422 passed responsibility for providing passage to Canada for all soldiers’ dependents from the Department of Mines and Resources, which was responsible for the Immigration Branch, to the Canadian military. The movement to Canada of “members of the forces” and “dependents” was closely defined and limited passages to “those who married abroad whilst serving abroad.”[5]

Canadian Military Authorities Regulate Overseas Marriages

In December 1944, the Canadian Army issued a directive regarding marriage in foreign lands: “marriage with a person of a different country, particularly by young soldiers, where there is a difference of religion, is open to obvious risks of future unhappiness.”[6] Commanding officers were instructed to refuse consent outright if they were “not satisfied that a reasonable basis for a happy marriage exist[ed] and in any event a four months’ waiting period will be imposed between the date of the granting of permission to marry and the date on which the marriage may be solemnized, unless there are circumstances [such as pregnancy] making the delay undesirable or unnecessary.”[7]

According to the Department of National Defence (DND), approximately 48,000 marriages with 22,000 childbirths were known to have occurred between 1942 and 1946. In all, 44,886 (93 percent) of these unions involved British women, followed by 1,886 (4 percent) with Dutch women, while 649 (1 percent) were with Belgian women. These marriages were not limited to the British Isles or northwest Europe, and included 362 marriages with women of other nationalities (see Table 1). Approximately 97 percent of all births resulting from these marriages were born to British women. Three Hungarian children were also listed in the DND statistics, but no war bride was counted as a mother suggesting that no marriage had taken place. It is possible that the latter were children who were born out of wedlock or were orphans adopted by Canadian military personnel.[8]

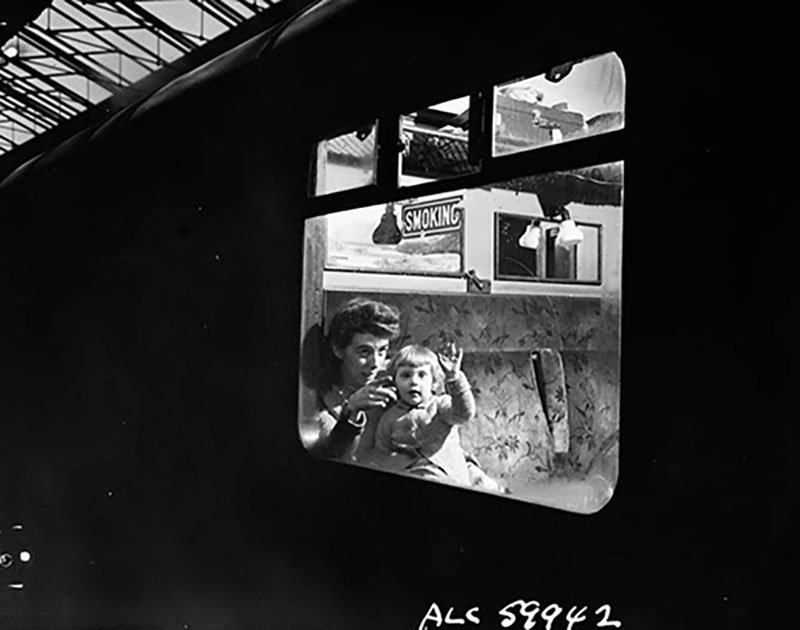

Credit: Lieut. Charles H. Richer / Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-128181

Canadian military authorities later acknowledged that a considerable number of marriages were not reported and allowances on behalf of dependents were not requested. Officials noted that records of these cases would “turn up at a later date.”[9] In all, 64,459 soldiers’ dependents consisting of 43,464 war brides and 20,995 children were brought to Canada between April 1942 and March 1948 (see Table 2). Three-fourths of the war brides and their children were brought to Canada after the end of the Second World War.[10] The vast majority of the war bride marriages involved men serving in the Royal Canadian Army (see Table 3).[11]

Prioritizing Continental War Brides after D-Day

After the Allied invasion on D-Day, 6 June 1944, newly liberated continental war brides increasingly became a priority for Canadian military authorities. Satellite bureaus were opened in Paris, Brussels, and The Hague to assist French, Belgian, and Dutch war brides with their resettlement to Canada.[12] Following the liberation of the Netherlands in 1945, Canadian troops were once again permitted to socialize with the local population as the war was coming to an end. Similar to the United Kingdom, Canadian servicemen and young Dutch women met in local pubs, theatres, dance halls, and at impromptu gatherings. These locations provided these young men and women with “an outlet and brief escapes from the realities of war.”[13] An unknown number of Canadian servicemen married Dutch women after 1946 as a result of having met them during the Liberation period.[14] War bride Kathleen Bilinski noted that “Canadian soldiers looked so nice, had money and told big stories about home.”[15] Aside from personal attraction, Dutch women had to prove that they were in good standing within their community in order to be permanently resettled by Canadian military authorities. In the Netherlands, a certificate of a woman’s political reliability had to be obtained from the Political Search Service or the Bureau of National Safety. Additionally, any Dutch woman who sought to marry a Canadian serviceman had to furnish a certificate of good moral conduct, normally from a priest or minister.[16]

With DND responsible for the transportation of soldiers’ dependents from 1944 onward, the department covered the costs of transportation within the United Kingdom (for British war brides), ocean transportation and meals, train fares, berths and meals to the final destination in Canada, as well as accommodations and hospitalization en route.[17] A majority of soldiers’ dependents were brought to Canada in 1946. One of the largest movements of war brides and children to Canada occurred on 10 February 1946, when 943 soldiers’ dependents aboard RMS Mauritania landed at Pier 21. Subsequently, the sailing of the last war bride transfer was scheduled to occur in January 1947 aboard RMS Aquitania. However, the movement of war brides and their children continued until 31 March 1948.[18]

Credit: Arthur L. Cole / Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-175803

Canadian Government Publishes Materials to Raise Awareness of Canada among War Brides

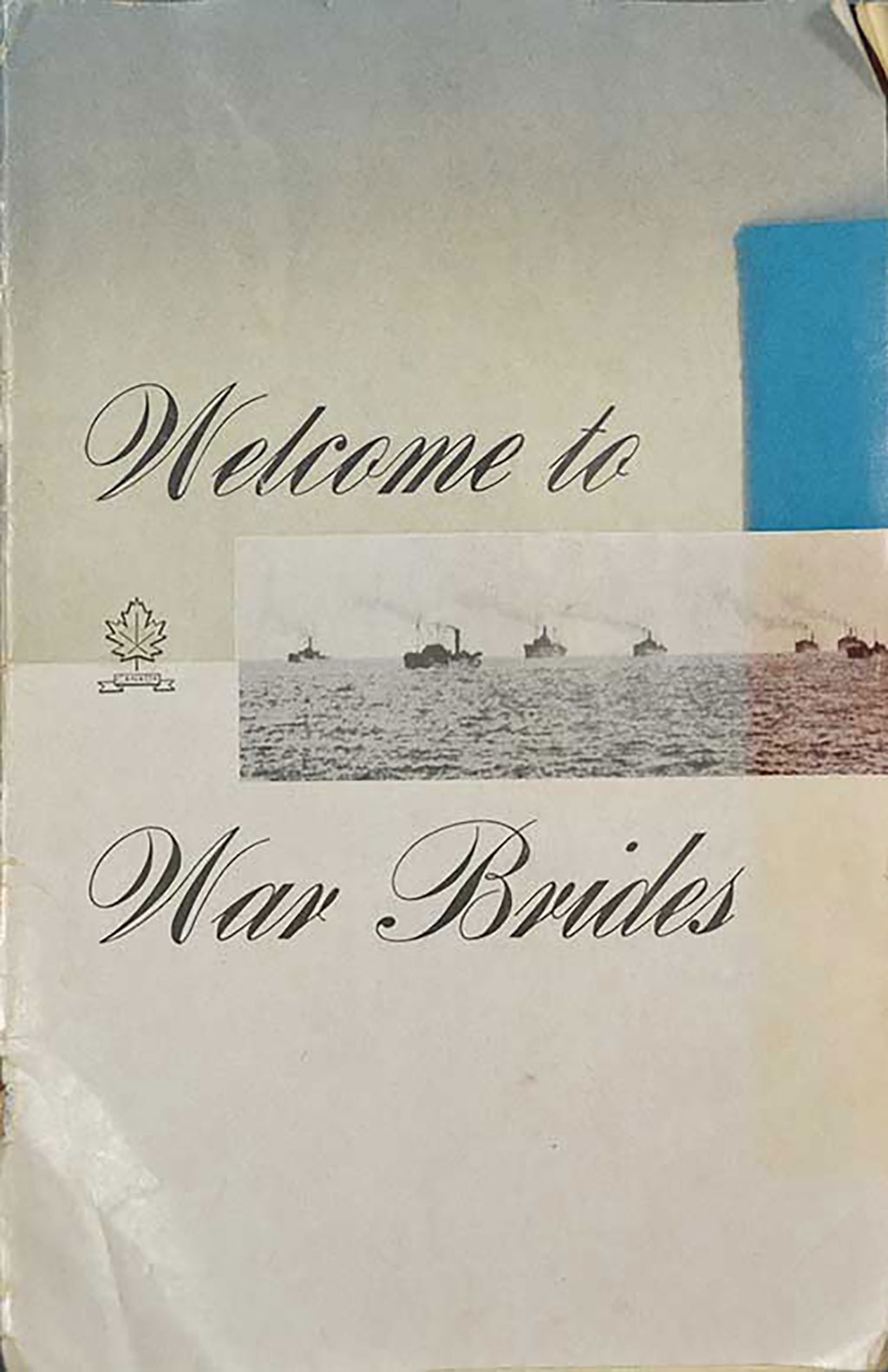

In an effort to raise awareness and reduce misunderstandings during resettlement to Canada, in 1944, the federal government published Welcome to War Brides in which, among other things, it informed the wives of Canadian servicemen that “when you arrive in Canada you will be met by Red Cross Workers who will give you all sorts of help, from a cup of tea to minding your baby, while you get through customs. If you desire, the Red Cross worker will telegraph your husband (if he is in Canada) or his family of your arrival.”[19] The publication proceeded to inform war brides that they should not spend too much time openly displaying their loneliness for their old friends and family, and homesickness for the old country. The booklet suggested they “keep busy and interested, that’s the best cure-all.” Welcome to War Brides further argued that the “Canadian people are not all the same.” Canadians in larger cities were deemed “less critical” although it took much longer to get to know them than in more rural areas. War brides were also informed that while their fellow Canadians would not interfere in their private lives, they would need to “conform to the community’s general standards, or live like a hermit and disappoint your husband and his people.” War brides were encouraged to engage in their local community and to “do as your neighbour does,” while expecting greater informality during social interactions with other Canadians unlike in the United Kingdom.[20]

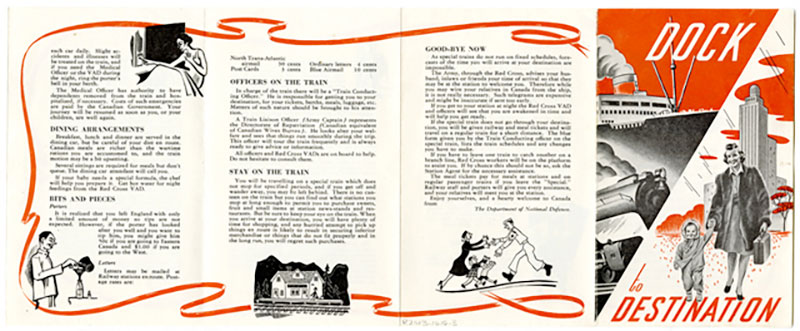

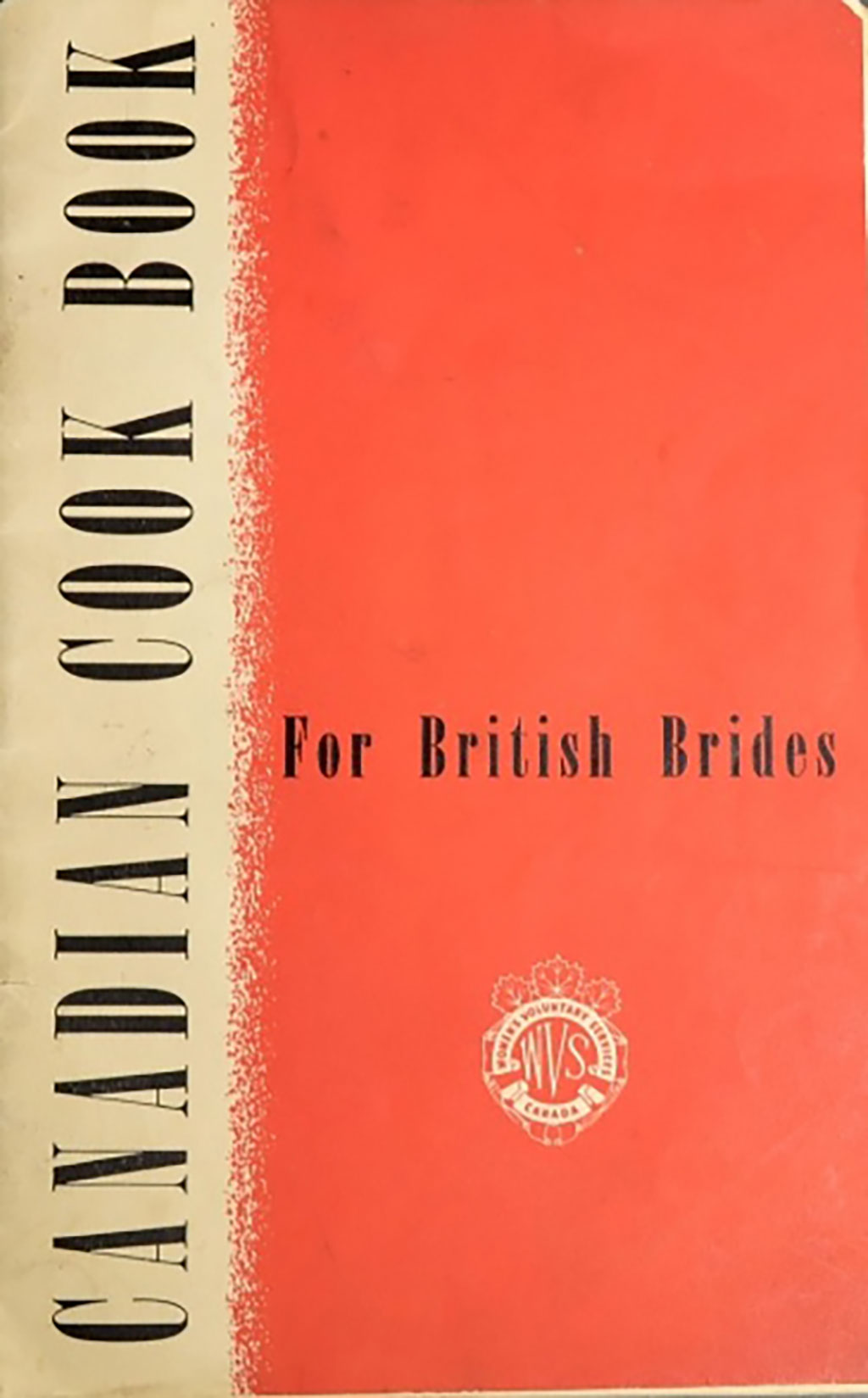

In March 1945, the DND published an informational booklet, To All Dependents: Your Journey to Canada, issued by the Canadian Wives Bureau in London, England. The 22-page booklet consisted of frequently asked questions and their subsequent answers. Queries included “to what does the scheme entitle a dependent?” and “is it possible to pay extra for higher class accommodation?”[21] British and continental European war brides were also provided a copy of Dock to Destination, a pamphlet detailing what they could expect once they arrived at a Canadian port of entry and offering hints and suggestions for a successful trip inland.[22] That same year, the Women’s Voluntary Services Division within the Department of National War Services created a Canadian Cookbook for British Brides which contained information on shopping, recipes, and cuts of meat among other items.[23]

Credit: "Welcome To War Brides," 1944. Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (R2013.1059.1)

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (R2014.479.36)

Credit: Pamphlet, "Dock to Destination," c. 1946. Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (R2013.1616.3)

Credit: Pamphlet, "Canadian Cook Book for British Brides," 1945. Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (R2013.908.2)

Non-governmental Organizations Publish Materials to Raise Awareness of Canada among the War Brides

Voluntary service agencies also produced materials for war brides and their children. The Imperial Order of the Daughters of the Empire (IODE) published From Kith to Kin, in which the organization informed war brides that “this booklet is our welcome until we can greet you in person in the land that we hope you will come to love, as we, who are its children, love it.” The booklet was divided into chapters such as “this Canada of ours” which included a discussion of accents, money, trains, land size, population, cities, homes, shopping clubs, racial strains, system of government, history, religions, schools, courts and legislation, and health and welfare. Subsequent chapters dealt with the environment and geography.[24]

Financial institutions joined the federal government and voluntary aid agencies in creating literature for the arrival of soldiers’ dependents to Canada. Hoping to capitalize on this sizeable movement of ‘preferred’ immigration, the Bank of Montreal released a pamphlet, Money Hints for the Serviceman’s Wife which contained information on how a war bride could use the bank to save or borrow money and to bank by mail. An inner flap consisted of a red-coloured door mat with the word “welcome” written in white and a caption, “so you’re going to be a Canadian…” The pamphlet also contained a diagram of Canadian currency and a list of various British currency and their Canadian equivalent.[25]

Transporting the War Brides and Their Children to Canada

Between 1942 and 1948, over 60 different ships including RMS Aquitania, RMS Franconia, RMS Mauretania, RMS Queen Elizabeth, RMS Queen Mary, SS Lady Rodney, SS Ile de France, HMHS Leticia, and SS Pasteur from the United Kingdom, France, Netherlands, Belgium, Ireland, Italy, and Newfoundland brought the war brides and their children to Canada, transporting over 97 percent of them to Pier 21 in Halifax where they were processed as immigrants.[26]

Credit: Barney J. Gloster / Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-175790

Canadian military officers directly involved in transporting war brides and their children to Canada shared in the DND’s belief that the war brides and their children were of “very fine stock.”[27] In an open letter titled “note of appreciation,” dated 12 October 1946, from the ship commandant to all soldiers’ dependents and civilian passengers aboard RMS Aquitania, Lieutenant-Colonel W.E. Sutherland wrote that…

There awaits you in the sheltered harbour of Halifax a welcome the warmth of which will extend from one end of the Dominion to the other. Canada welcomes you with a deep feeling of pride…British and Dutch stock such as this is indeed a welcome addition to our Country; and your lovely children, the likes of which I have never seen surpassed, should grow up under Canada’s sunny skies, true stalwarts of parents who have proven their worth as real men and women – and on their shoulders will rest the future responsibility of guiding the National Affairs of State and the future destiny of Canada.[28]

War Brides and Their Children Arrive at Pier 21

While war brides and their children were heartedly welcomed by Canadian officials during their “repatriation,” to Canada, they had diverse experiences upon landing at Pier 21. War bride Ruby Dunham recalls that “it took us about 5 days till we got to Halifax and we were almost a full day until they allowed us off the ship. We went off in batches.”[29] Eva Wrigley remembers that when her ship “pulled into Halifax Harbour and most of the troops disembarked; the war brides spent one more night on board.”[30] Margaret Macaulay remembers that she landed “early on the morning of 11 August, 1946, I was happy to see that the fog has lifted and we were docked at Pier 21. We disembarked with the aid of soldiers assigned to carry our luggage and Peter [her son] in the carry-cot.”[31] British war bride Sylvia M. MacDonald recollects that she arrived at Pier 21 in June 1946 with her two year-old son, Alastair Douglas and “we were aboard the Queen Mary with many War Brides and their children. Each of us was met by a serviceman, who picked up my 2 year old and a Red Cross Worker, who carried my cabin baggage. They knew where to find my husband, Alastair Edwin in the large building, so full of people waiting to meet us. A.D. put out his arm for his daddy to take him. With his other arm around me, we were together after a year of waiting.”[32]

While larger groups arrived to cheering Canadians and much fanfare, others arrived quietly to an empty hall and no celebration. For many of the war brides, the trip to Canada was the first time they had ever travelled far from home. Many were also young adults who arrived with small children and lacking information about Canadian culture and customs.[33] Dutch war bride Olga Rains (neé Trestorff) remembers arriving at Pier 21…

We were all so glad when Canada came into sight and could hardly wait to get off the boat and be on our way. We arrived at PIER 21. For some brides the husbands were waiting, but for others it was different. We were told to check the bulletin board in the big hall. There were messages for the brides. One of the brides on this boat got the brush off from her husband. He had changed his mind and told her to go back to England. Each Bride was escorted off the boat by a soldier who brought us to a huge building. There we had to hurry up and wait in line. Our papers were checked and again we were escorted to the train.[34]

Repatriated Canadian Citizens or Landed Immigrants? Processing War Brides through Pier 21

Upon entering Pier 21’s immigration facility, the war brides’ Travel Certificate documents were processed by Canadian officials who stamped “Landed Immigrant” on the aforementioned papers. War bride Jeanne Perry landed at Pier 21 in April 1946 aboard HMHS Leticia. According to Perry, Canadian military personnel subsequently checked her papers, however, they mistakenly informed her that the Canadian Travel Certificate in her possession was a proof of citizenship. Many individuals within Canadian society and the mainstream press perceived the war brides and their children to be Canadian citizens who were in the midst of “repatriation,” but in reality their official status was quite different. “Landed Immigrant” status permitted war brides to live in Canada permanently, but as Sydney Matrix points out, unless they later completed the requisite forms to acquire Canadian citizenship, the war brides and their children would not legally hold Canadian nationality.[35] Many war brides were later dismayed to discover this fact. In the mid-2000s, the war brides’ citizenship issues garnered national attention. Lobbying efforts by their descendants and supporters eventually led to the implementation of Bill C-37, an Amendment to the Citizenship Act, commonly referred to as the “Lost Canadian Bill.” In April 2009, the amendment came into force. Yet, some of the war brides’ children remain without Canadian citizenship due to the circumstances of their birth, in particular being born out of wedlock.[36]

Some of those born out of wedlock point to Order-in-Council P.C. 1945-858, a wartime regulation passed by the federal cabinet, in 1945, that permitted every dependent of Canadian service personnel to apply for admission to Canada. Section two of the Order-in-Council stated that every dependent applying to enter the country “be permitted to enter Canada and upon such admission shall be deemed to have landed within the meaning of Canadian immigration law.” Section three of the regulation noted that

Every dependent who is permitted to enter Canada pursuant to section two of this Order shall for the purpose of Canadian immigration law be deemed to be a Canadian citizen if the member of the forces upon who he is dependent is a Canadian citizen and shall be deemed to have a Canadian domicile if the said member has Canadian domicile.

According to the Lost Canadians advocacy group, Order-in-Council 1945-858 recognized the status of arriving military dependents under existing laws, which meant that these children were viewed as returning Canadians rather than as immigrants at the time.[37] This assertion has been brought before the Canadian Courts, most notably in 2006, with Taylor v. Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration).[38] In September 2006, the Federal Court of Canada ruled that an individual born out of wedlock to a Canadian serviceman father and a non-Canadian mother acquired citizenship upon arrival in Canada after the Second World War without having subsequently lost their citizenship while living aboard. In November 2007, the Federal Court of Appeal overturned the 2006 ruling arguing that Taylor had lost his Canadian citizenship under section 20 of the 1947 Canadian Citizenship Act because he had been absent from Canada for more than ten consecutive years. The Court of Appeal noted that Taylor could request Canadian citizenship under section 5(4) of the current citizenship act as a special case. In December 2007, Taylor was granted Canadian citizenship.[39]

Red Cross Workers Assist in the Departure of War Bride Trains from Pier 21

Pier 21’s immigration quarters were reoccupied by Canadian immigration and customs officials, and various voluntary service agencies in December 1946. The service agencies including the Imperial Order of the Daughters of the Empire, the Canadian Red Cross, and the Young Women’s Christian Association were ready to assist the war brides and their children. These volunteer groups were instrumental in answering their questions, helping care for their children, making sure they had the right documentation and ensuring they boarded the proper “War Bride Trains” heading westward across Canada to their final destination, where their Canadian husband was hopefully waiting in anticipation.[40] War bride Marjorie Davidson recalls that “being greeted by Red Cross people, offering us coffee and doughnuts, cheered us up somewhat, as we were welcomed to Canada and wished good luck. We realized this was Canada, and we would learn to live in it.”[41] As a Volunteer Aid Detachment, a number of Canadian Red Cross Escort Officers, representing every province, assisted the war brides and their children during this journey from Europe to Canada. Ten officers joined from Halifax: Jeane Doane, Pat Keen, Mrs. Postyn, May Feetham, Helen Black, Pippa Stevens, Mary Sellers, Mrs. Moorehouse, Mrs. O’Neil, and Mrs. Goodeve.[42]

In cooperation with the federal government, the Canadian Pacific Railway, the Canadian National Railway, and the Canadian Red Cross organized a disembarkation program with bureaus across Canada. After the final destination of each war bride and child was listed, the information was sent to the Embarkation Transit Unit Movement Control in Halifax.[43] The unit was composed mainly of Red Cross workers, who helped war brides and their children find special trains scheduled to transport them across Canada to their final destination. The unit was also responsible for notifying Canadian families to be prepared for their arrival.[44]

War Brides Travel by Train to Final Destinations across Canada

In December 1946, a Dutch war bride, Catherina Vermaesen, and her six-month old son landed at Pier 21 aboard SS Empire Brent. She traveled from the Netherlands with two pieces of luggage, one for clothes, the other – a baby basket containing her son, Roméo. He was born the previous July to Vermaesen, a Dutch nurse, and a Canadian serviceman, Sergeant Roméo Louis Dallaire. Six-month-old Roméo and his mother were processed by Canadian officials following their disembarkation. The family was assisted by the Red Cross through the immigration facility and moved to a waiting Red Cross train. The Red Cross trains were destined for different regions across Canada, and would stop in different locations where existing information indicated that a military member or their family resided, or where a war bride and child were to depart from the train having arrived at their new home.[45]

Roméo Dallaire notes that when he and his mother joined other soldiers’ dependents aboard a train heading west “in December, it was cold, coming from Europe and war-torn countries, and the train stopped in the middle of the night at Saint Louis-du-Ha! Ha!, [Quebec] where there was a little cabin built by CN and a 25-watt light bulb burning. As they looked to both ends of the train, no one was there. A number of these war brides arrived to no one being there.” Dallaire notes that in urban centres across Canada, the Red Cross organized efforts to help war brides return home, which was unpopular because they had married Canadian servicemen and would face stigma upon returning to their old country. War brides could also receive assistance from local community services to begin new lives.[46]

Minority of War Brides Return to Their Home Countries

Author Peggy O’Hara claims that ten percent of the war bride movement returned to their home country within a year of arriving in Canada.[47] Other war brides and grooms never arrived in Canada due to what officials described as a “nervous collapse.”[48] In some cases, war brides arrived in Canada only to learn that their Canadian soldier husband was already married or desired a divorce, or never met his wife at the train station upon her arrival. Others had difficulty adjusting to their new lives and new in-laws in Canada and returned home to be with family among familiar surroundings.[49]

Conclusion

This unique movement represents the single largest contiguous wave of migration to Canada, specifically through Pier 21. With federal immigration officials lukewarm to the idea of bringing soldiers’ dependents to Canada, the impetus behind the resettlement scheme was due in large part to the Department of National Defence and Canadian military authorities. Soon thereafter, the Canadian military cooperated with the Immigration Branch to bring the first significant wave of postwar immigration to Canada: Polish veterans in the United Kingdom and Italy, who refused to be repatriated to their homeland after it was liberated by Soviet forces.

Table 1 - Known Marriages and Births for Servicemen Married while Serving Outside Canada to 31 December 1946[50]

| Country of Origin | Wives | Children |

| Great Britain | 44,886 | 21,358 |

| Netherlands | 1886 | 428 |

| Belgium | 649 | 131 |

| Newfoundland & Caribbean | 190 | |

| France | 100 | 15 |

| Italy | 26 | 10 |

| Australia | 24 | 2 |

| Denmark | 7 | 1 |

| Germany | 6 | 2 |

| Malay | 2 | |

| Norway | 1 | |

| North Africa | 1 | |

| South Africa | 1 | |

| Greece | 1 | |

| Algiers | 1 | |

| Russia | 1 | |

| India | 1 | |

| Hungary | 3 | |

| TOTAL | 47,783 | 21,950 |

Table 2 - Repatriation of Dependents of the Canadian Armed Forces to Canada, April 1942 to March 1948[51]

| Year | Wives | Children | Total |

| 1942-1944 | 3,319 | 2,002 | 5,321 |

| 1945 | 6,972 | 3,705 | 10,677 |

| 1946 | 31,807 | 14,272 | 46,079 |

| 1947 | 1,310 | 954 | 2,264 |

| 1948 | 56 | 62 | 118 |

| TOTAL | 43,464 | 20,995 | 64,459 |

Table 3 – Armed Services in which Canadian Husbands Served[52]

| Canadian Military Service | Wives | Children |

| Royal Canadian Army (RCA) | 80% | 85.5% |

| Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) | 18% | 13.1% |

| Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) | 2% | 1.4% |

| TOTAL | 100% | 100% |

- Library and Archives Canada (hereafter LAC), Statutes of Canada, An Act Respecting Immigration, 1910 (Ottawa: SC 9-10 Edward VII, Chapter 27); LAC, Privy Council Office fonds, RG 2, vol. 1479, “Orders in Council – Décrets-du-Conseil,” PC 1931-695, 21 March 1931.↩

- Valerie Knowles, Forging Our Legacy: Canadian Immigration and Citizenship, 1900-1977 (Ottawa: Public Works and Government Services, 2000), 66.↩

- LAC, Department of National Defence (hereafter DND) fonds, RG 24, file HQS 8536-1 “Return to Families of Canadian Officers and Service Personnel to Canada, 1940-1951,” report “History of S.A.A.C. Office and Directorate of Repatriation, 1942-1947,”, n.d., 32, reel C-5220.↩

- “History of S.A.A.C. Office and Directorate of Repatriation, 1942-1947,” 26-27.↩

- LAC, DND fonds, RG 24, file HQS 8536-1 “Return to Families of Canadian Officers and Service Personnel to Canada, 1940-1951,” memo from Colonel George H. Ellis, Director of Repatriation to Major-General B.W. Browne, Assistant National Commissioner, Canadian Red Cross, 29 January 1947, reel C-5220.↩

- Michiel Horn, “Canadian Soldiers and Dutch Women after the Second World War,” in Dutch Immigration to North America, eds. Herman Ganzevoort and Mark Boekelman (Toronto: Multicultural Historical Society of Ontario, 1983), 193.↩

- “History of S.A.A.C. Office and Directorate of Repatriation, 1942-1947,” 32.↩

- “History of S.A.A.C. Office and Directorate of Repatriation, 1942-1947,” 34. In total, 47,783 marriages with 21,950 childbirths occurred between 1942 and 1946. See Table 1 – “Known Marriages and Births for Servicemen Married while Serving Outside Canada to 31 December 1946"↩

- “History of S.A.A.C. Office and Directorate of Repatriation, 1942-1947,” 34.↩

- LAC, Department of Citizenship and Immigration fonds, RG 26, vol. 143, file 3-40-21, “Statistics: Ten Years of Post-War Immigration,” report, George E. Fincham, “A Statistical Survey of Immigration to Canada,” April 1952, 33. See Table 15.↩

- See Table 3 – Armed Services in which Canadian Husbands Served.↩

- Memo from Colonel George H. Ellis, Director of Repatriation to Major-General B.W. Browne, Assistant National Commissioner, Canadian Red Cross, 29 January 1947.↩

- Jay Bodrog, ed., The War Brides of Perth County (Stratford: Perth County Historical Foundation and Stratford Perth Museum, 2009), 2.↩

- Horn, “Canadian Soldiers and Dutch Women after the Second World War,” 192.↩

- Bodrog, War Brides of Perth County, 2.↩

- Horn, “Canadian Soldiers and Dutch Women after the Second World War,” 193.↩

- “History of S.A.A.C. Office and Directorate of Repatriation, 1942-1947,” 30. This information is also available online. See Canadian War Brides (hereafter CWB), “Transportation Statistics,” accessed on 6 February 2014, http://www.canadianwarbrides.com/cwbstats1.asp.↩

- CWB, “Transportation Statistics;” Knowles, Strangers at Our Gates, 162. The average cost per adult passenger was $140.29.↩

- Bodrog, War Brides of Perth County, 17.↩

- “Welcome to War Brides,” 1944. Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier at 21 Collection (hereafter CMI) (R2013.1059.1). See page 22.↩

- DND, “Your Journey to Canada,” 1 March 1945. CMI Collection (R2013.1061.1).↩

- Pamphlet, “Dock to Destination,” circa 1946. CMI Collection (R2014.135.3b).↩

- Yvonne Fortune, 1945. CMI Collection (R2013.908.2).↩

- Shawn Jeffrey, circa 1945, CMI Collection (DI2015.585.1). See page 1. From Kith to Kin was published by Runge Press Limited, Ottawa.↩

- Pamphlet, “So You’re Going to be a Canadian,” circa 1945. CMI Collection (DI2015.154.17).↩

- Alexa Thompson and Debi van de Wiel, Pier 21: An Illustrated History of Canada’s Gateway (Halifax: Nimbus, 2002), 83.↩

- See footnote 13.↩

- Letter from Lieutenant-Colonel W.E. Sutherland, “To All Canadian Troops-Dependents and Civilian Passengers on Board H.M.T. ‘Aquitania,’” 12 October 1946. CMI Collection (DI2013.1046.1a). See page 1.↩

- Ruby Dunham, One Seel Less One Dunham More: A Love Story (Owen Sound: Memory Catchers, 2013), 21.↩

- Eva Wrigley, To Follow a Cowboy (Salmon Arm: Hucul Printing, 1999), 45.↩

- Margaret Macaulay and Horace Macaulay, Surrey Girl (not just another war bride) (Nepean: HRM Publishing, 2001), 39.↩

- Immigration Story of Sylvia M. MacDonald (War Bride). CMI Collection (S2012.1873.1).↩

- Trudy Duivenvoorden Mitic and J.P. Leblanc, Pier 21: The Gateway That Changed Canada (Halifax: Nimbus, 2011), 52.↩

- Olga Rains, “A Dutch War Bride,” in The Land Newly Found: Eye Witness Accounts of the Canadian Immigrant Experience, eds. Norman Hillmer and J.L. Granatstein, 217-220 (Toronto: Thomas Allen Publishers, 2006), 218.↩

- Sidney Eve Matrix, “Mediated Citizenship and Contested Belongings: Canadian War Brides and the Fictions of Naturalization,” Topia: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies 17 (2007): 73.↩

- CWB, “Passport and Citizenship Issues of War Brides and their Children,” accessed 25 September 2017, http://www.canadianwarbrides.com/passports.asp.↩

- For further context, see R.H. Addington, “Order in Council P.C. 1945-858 and the Lost Canadians: A gateway to Canadian citizenship,” May 8, 2012, http://blog.lostcanadian.com/2012/05/order-in-council-pc-1945-858-and-lost.html.↩

- Joseph Taylor is the son of a Canadian serviceman and a British mother, who was born out of wedlock in England in 1944. His parents subsequently married in May 1945. After the Second World War, Taylor’s father returned to Canada and was later followed by Taylor and his mother in July 1946. The marriage soon broke down and Taylor and his mother returned to England, six weeks before the 1947 Canadian Citizenship came into effect. For further context, see Stacey A. Saufert, “Taylor v Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration): Discrimination, Due Process, and the Origins of Citizenship in Canada,” Alberta Law Review 45.2 (2007): 522-523.↩

- “Federal Court of Appeal Decisions: Canada (Citizenship and Immigration) v. Taylor [2007 FCA 349],” Federal Court of Appeal, https://decisions.fca-caf.gc.ca/fca-caf/decisions/en/item/35761/index.do?q=taylor+2007. See paragraphs 82-84 and the conclusion.↩

- Thompson and van de Wiel, Pier 21, 83.↩

- Marjorie Davidson, Against the Tide (Summerland: Valley Publishing, 2000), 42.↩

- CWB, “Red Cross Escort Officers List,” accessed on 6 February 2014, http://www.canadianwarbrides.com/immigrationstats.asp.↩

- Ben Wicks, Promise You’ll Take Care of My Daughter: The Remarkable War Brides of World War II (Toronto: Stoddart Publishing, 1992), 91.↩

- Canada’s Historic Places, “Pier 21 and Canada’s War Brides,” accessed 3 February 2017, http://www.historicplaces.ca/en/pages/36_pier_21.aspx.↩

- Parlinfo, “Maiden speech of Roméo Dallaire,” accessed 2 April 2019, https://lop.parl.ca/staticfiles/ParlInfo/Documents/MaidenSpeech/En/Dallaire_Romeo_sen.pdf; CWB, “Passport and Citizenship Issues of War Brides and their Children.” See “May 7, 2005.”↩

- Roméo Dallaire, “Expression of Thanks to Canada – The Red Cross War Brides of WWII,” accessed 1 May 2015, http://romeodallaire.sencanada.ca/en/p103405/.↩

- Peggy O’Hara, From Romance to Reality: Stories of Canadian WWII War Brides (Cobalt: Highway Book Shop, 1985), 290.↩

- Wicks, Promise You’ll Take Care of My Daughter, 91. The term was used to depict an individual’s mental breakdown: acute and time-limited cases of stress, anxiety or disassociation.↩

- CWB, “Immigration to Canada by War Brides and Their Children 1942-1948,” accessed on 6 February 2014, http://www.canadianwarbrides.com/immigrationstats.asp; CWB, “Transportation Statistics,” accessed on 6 February 2014, http://www.canadianwarbrides.com/immigrationstats.asp. Table originally appeared in Melynda Jarratt, “The War Brides of New Brunswick” (M.A. Report, University of New Brunswick, 1995), 12. See also Thompson and van de Wiel, Pier 21, 83; O’Hara, From Romance to Reality, 290.↩

- LAC, DND Fonds, RG 24, file HQS 8536-1, “Return to Families,” report “History of S.A.A.C. Office and Directorate of Repatriation, 1942-1947,” 32. Table 1 does not include unclaimed war births↩

- Fincham, “A Statistical Survey of Immigration to Canada,” April 1952, 33.↩

- “History of S.A.A.C. Office and Directorate of Repatriation, 1942-1947,” 34.↩