by Jan Raska, PhD, Historian

(Updated July 6, 2020)

At that time…[there were]…no buses running, it was like a strike, all the transportation. So I remember…we were scared…we didn’t know what was going on, that it’s going to be…more like a coup—in those days I didn’t know what a coup was. We only knew that we elect[ed] a president…in a couple of days…everything seemed to be back to normal life. We start[ed] to have those problem[s]…no[t] be able to buy milk, no[t] be able to buy, anything. We have the money, but we couldn’t find anything. So this was the time of long lineup[s] to buy anything…I remember…I went to visit my mom…it was September 11, 1973. Everything changed. Everything changed.[1]

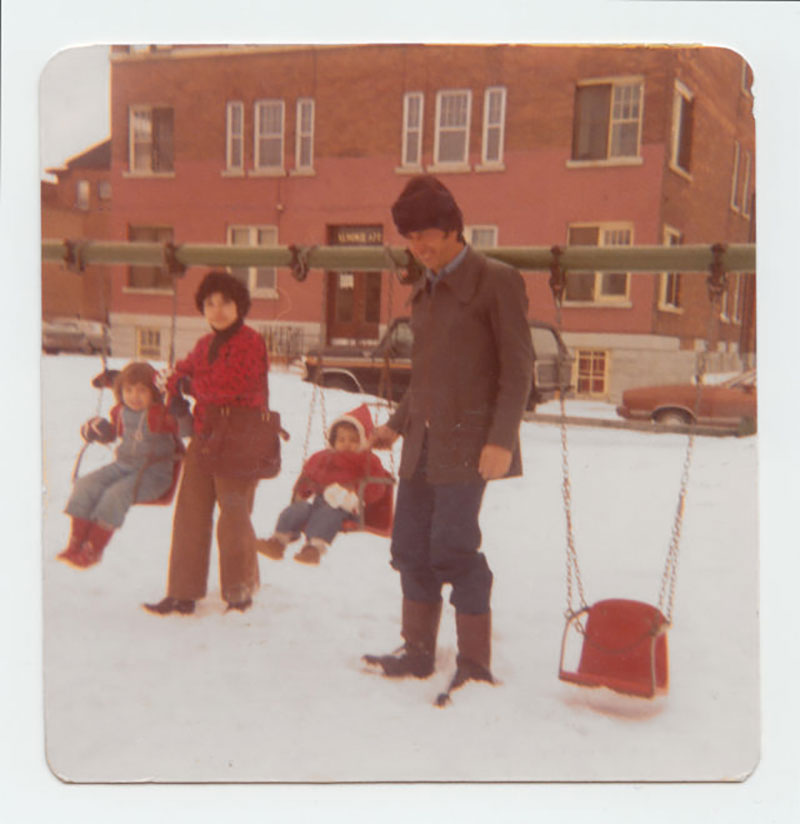

- Ruth Miranda, who supported the left-wing government of Salvador Allende, later arrived in Canada from Chile in 1979.

Credit: Ruth Miranda, arrived from Chile, 1979. Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (DI2017.802.2)

Introduction: Chile before the 1973 Coup d’état

Until the late 1960s, Chile remained a prosperous and stable Latin American country. Chile attracted immigration from neighbouring countries, Europe, and to lesser extent, Arab states. In the free elections of 1970, Salvador Allende, who led the Unidad Popular (Popular Unity) coalition – a left-wing political alliance comprised of social democrats, socialists, radicals, populists, and communists – came to power. The United States government and its allies viewed Allende’s victory as a threat to Cold War democratic values and American hegemony in Latin America. The Allende government’s implementation of wide-ranging socioeconomic reforms including the nationalization of many foreign companies (mainly American) heightened the concerns of Western officials. Tensions further increased when Chilean authorities attacked the holdings of large landowners in order to correct the unequal distribution of income and concentration of economic resources throughout the country.

Some Chileans feared that these early steps would lead the country towards communism. As Allende’s coalition achieved greater public support in the midterm congressional elections, in September 1973, General Augusto Pinochet – with the support of the Central Intelligence Agency – staged a coup d’état. The coup displaced left-wing elements in the Chilean government and led to the death of Allende.[2] The coup shocked international observers as the Chilean military traditionally supported its civilian government leaders. In addition, the election of Allende to the presidency in 1970 marked the first time a Socialist had been elected to the country’s highest office through entirely democratic constitutional means.[3]

Historian Francis Peddie notes that many Chileans expected the military intervention to be short and for the status quo to return. However, Chilean society soon witnessed the beginnings of a regime that would last nearly seventeen years. Pinochet’s authoritarian government implemented state-wide repression, in an effort to rid Chile of leftist dissent. The military junta claimed that in order to achieve prosperity, ‘real’ economic liberty in the free market had to substitute old political freedoms and the latter stifled the country’s development. Consequently, the new government used coercion and exclusion to eliminate or replace opposition to its rule.[4]

Pinochet Regime: From a Campaign of Attacks and Repression to a Refugee Crisis

In the following weeks, Pinochet’s regime commenced a brutal campaign of attacks and used direct and indirect methods of repression. They ranged from assassinations, disappearances, and blacklisting to coercion, isolation, and exclusion – all aimed at ridding Chile of leftist opposition. While thousands were imprisoned or killed, others suffered prolonged detention and torture. The Chilean Armed Forces and the national police force (Carabineros de Chile) were responsible for killing at least 2,000 people during the initial crackdown. Up to 80,000 Chileans were detained for at least twenty-four hours between September 1973 and January 1974.

The most intense violence against the Chilean population occurred in the first six months after the coup. Afterwards, indirect repression and suppression of human rights continued for the entire existence of the military junta. In addition to purging members and sympathizers of the Unidad Popular coalition from the public service and education system under a process known as exoneración, the military junta also subjected the media to severe scrutiny and closed down presses, publishing houses, and radio stations that sympathized with the Allende government. The new government suspended the rule of law by declaring a state of war and increased its own power to detain, search, and question Chilean citizens. It referred to its opponents as “enemies of liberty.” Given these conditions, over 200,000 Chileans sought safe haven elsewhere.[5]

At the time of the coup, a large number of non-Chilean Latin Americans resided in the country. Many of them were Brazilians, who had fled repressive conditions under the military dictatorship in their home country and resettled in Chile during Allende’s presidency. Others were international university students or workers. Soon, Pinochet’s regime viewed this population as a threat and commenced efforts to intern or imprison this foreign population. After Allende’s suicide on 11 September 1973, his supporters fled for neighbouring countries or sought asylum in foreign embassies in the capital, Santiago. Meanwhile, the non-Chilean refugees who fled the country or sought sanctuary in foreign embassies were the first to receive assistance from the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).[6]

Canadian Churches and Voluntary Service Organizations Lobby Ottawa to Resettle Chilean Refugees

In the days following the coup d’état, church groups and humanitarian organizations called on the Canadian government to respond to the plight of Chilean refugees. These groups and their supporters undertook a letter-writing campaign to raise public awareness of the sudden crisis in Chile. On 14 September 1973, representatives of the United Church, Anglican Church, and the Canadian Catholic Conference sent the following telegram to the Secretary of State for External Affairs, Mitchell Sharp, in Ottawa:

…One thing is clear, that a democratically-elected government has been violently overthrown. We can only hope and pray that violence will not generage [sic.] further violence. We caution against precipitous recognition of an unconstitutional regime. We request the Canadian government to do its utmost so that constitutional government be restored as soon as possible. A particular aspect of the Chilean situation is of special concern. Many refugees are presently living in that country. We strongly urge the Canadian government to offer safe conduct and assistance to those refugees and any Chileans who may wish to come to Canada.[7]

Despite the concerns of church groups, Canadian officials soon recognized the Pinochet-led military junta as the legitimate government of Chile.

As a Canadian immigration official at the time of the Chilean crisis, Michael Molloy recalls that federal officials received thousands of letters sent to them by enthusiastic church groups who wished to bring Chilean refugees to Canada. Every letter had to be answered, which kept Canadian officials very busy.[8] Molloy points out that before the Chilean movement, the refugee constituency in Canada was predominantly of a European background. Once these individuals resettled in Canada, they sought ways to get their compatriots out from their oppressive regimes at home. While many Canadian churches were interested in the plight of refugees, it was Canada’s Eastern European and Jewish communities and a few Canadian churches that led these resettlement efforts. In particular, the Anglican, United, and Catholic Churches maintained relations with their fellow churches in Latin America.

Furthermore, Molloy claims that “I don’t think the government of Canada was even vaguely aware of it. And it…came as a great shock to realize that…very influential churches cared deeply about what was going on in there.[9] Given these ties to Latin America, Canadian Churches, voluntary service organizations, and refugee rights advocates demanded that the Canadian government grant refugee status to the Chileans.[10]

The Canadian Council of Churches also appealed to the federal government to help Chilean and other Latin American refugees following the coup:

It is based upon humanitarian and not political considerations. Since these refugees are in danger of their lives, under a very repressive military regime, we have only one option: to do what we can to save these lives. Canada opened her doors to refugees from Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Uganda. If we refuse to open our doors to people who are in danger under another type of political regime, this would mean that we had acted from political rather than humanitarian motives.

Mitchell Sharp responded to the council by suggesting that Canada would provide safe passage to refugees seeking to enter Mexico from the Canadian embassy in Santiago, Chile. In October, Canada had not yet publicly pronounced its policy towards those refugees fleeing the Pinochet military regime.[11]

Cold War Politics: Canadian Officials Wary of Chilean Refugees due to Ideological and Security Concerns

Initially, Canadian officials were cautious to resettle Chilean refugees in Canada. Worried about the possible leftist sympathies of the Chilean refugees, Canadian officials provided little government planning and assistance to individuals fleeing the repressive right-wing military regime. Aware of American support for the new Pinochet government and uncertain about the political affiliation of the aforementioned refugees, the Canadian government acted slowly for nearly a year before implementing rigid security screening to prevent communist sympathizers from entering Canada.

Soon, the Canadian government was criticized for its inaction in bringing Chilean refugees to Canada. With heightened public awareness and lobbying efforts on the part of the UNHCR, Amnesty International, Canadian churches, and voluntary service organizations, the federal government loosened selection criteria and exclusionary measures to permit nearly 7,000 refugees from Chile to enter Canada.[12]

The Academic Community Expresses Solidarity with the Refugee Scholars and Pressures Ottawa to Respond

In the months that followed the coup, Canada’s university and college community expressed its solidarity with scholars in Chile and explored ways in which to bring these individuals to Canada. The academic community in Canada recognized that the coup had consequences for Chilean scholars – many of whom were persecuted by the Pinochet regime for their support of the deposed Allende government.

In a letter to Mitchell Sharp in October, Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT) stated... “We believe that the Canadian government has an admirable record in relation to its assistance to the victims of oppression, notably in Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Uganda. We consider that the situation of academics in Chile is analogous with that of Czechoslovakia in that many academics perceive that the result of military force is likely either to endanger their lives or to eliminate the possibility of academic freedom.”[13] CAUT pointed to the precedent set during the resettlement of Prague Spring refugees when the Canadian government gave Czech and Slovak refugee students financial assistance in the form of a fifty-fifty loan-grant of $1,200, and provided English- or French-language courses for up to six months combined with a living allowance. Meanwhile, refugee professors received special grants and Canadian officials encouraged universities to match these funds up to $6000. In its letter to the minister, CAUT went on to request a similar program for Chilean refugees.[14]

Meanwhile, the Social Science Research Council of Canada’s executive director, Dr. John Banks petitioned the heads of social science departments at Canadian universities to help bring Chilean scholars to Canada by finding them academic positions within their faculties. While the departments were generally sympathetic and recognized that they had a role to play, some department heads replied to Banks that the Chileans would be judged on their own merits and in competition with other scholars. Others indicated that their departments did not have adequate funds to support additional academic positions.[15]

On behalf of the Canadian University Committee for Refugee Chilean Professionals and Students, Professor Lionel Vallée visited Chile on a fact-finding mission to assess the local conditions under the military regime. Between 30 November and 23 December, Vallée found that nearly everyone in the country had a friend or relative harassed, tortured, imprisoned, took asylum in a foreign embassy, sought refuge aboard, ran away, or died at the hands of the authorities.[16]

Canadian Government Responds to the Crisis by Offering Three Types of Sanctuary

Previous scholarship points to American influence in the Canadian government’s response to the Chilean crisis. However, recent research suggests that Canadian officials conceptualized and implemented their own policies without excessive external influence. Cognizant of the decisions formulated by other Commonwealth and Latin American states, Ottawa chose to recognize the Pinochet-led military junta in order to protect Canadian economic interests, including existing trade agreements. Due to growing public pressure for action, federal officials soon indicated that any future plan to help refugees would be structured around a security and humanitarian response. Humanitarianism scholar Suha Diab argues that “cultural racism” – the exclusion of cultures that do not espouse an adherence to Western liberal values including individual enterprise and liberty – and attempts to prevent the spread of communist ideology and Quebec separatism as part of safeguarding Canadian interests, outweighed the predicament of Chilean refugees.[17]

During the Chilean crisis, the Secretary of State for External Affairs, Mitchell Sharp, informed the press of Canada’s policy regarding asylum. The secretary of state for external affairs declared that three types of sanctuary were possible: territorial asylum, diplomatic asylum, and temporary shelter. For territorial asylum, the applicant had to be within the state where he or she was seeking asylum and had to show a “well-founded fear of persecution” (as defined in the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees) if they were to return home. The second category dealt with granting an applicant permanent asylum within an embassy or legation. The third type was for situations where an individual indicated to Canadian officials at a diplomatic post that their life was in imminent danger. This form of temporary safe haven would only last until permanent arrangements could be made for the applicant. Approximately 50 individuals received this form of protection.[18]

On the Right Side of the Cold War? Diplomatic Controversy

Despite lobbying efforts on the part of prominent organizations and groups, Canadian officials remained reluctant to implement a liberal refugee policy as they did with the Hungarian, Czechoslovak, and Ugandan Asian movements. This was in part due to Cold War ideology, in which the Canadian government viewed communist regimes as refugee-producing states, while individuals fleeing right-wing regimes were considered ‘undesirable’ due to their suspected leftist political backgrounds.[19] In late September, a diplomatic controversy shed further light on these ideological tensions. In his correspondence with the Department of External Affairs, Canada’s ambassador to Chile, Andrew Ross, defended the military coup and claimed that the Chilean leftists, who sought asylum in Canada, were “riff-raff.” Bob Thomson, an official with the Canadian International Development Agency was outraged by these views, and leaked the diplomatic cables between Ottawa and its ambassador in Santiago to the press.[20]

Public Pressure and Lobbying Efforts Succeed: Canada Sends Immigration Officials to Chile

In mid-October, the Canadian government announced that its officials stationed in Argentina would be sent to Chile since there were no immigration personnel in the country. At the time, approximately twenty refugees were able to reach Canada from states of first asylum in Latin America where they obtained visas from Canadian officials. Late in November, Canadian immigration officials reached Chile and began screening and processing applicants for resettlement in Canada. With no set allotment, observers soon believed the Chilean movement would be smaller than the Hungarian (1956-1958) and Czechoslovak (1968-1969) resettlement schemes.

The detailed procedures, intensive security screening, and lack of translators were all factors that limited the process. The stringent process soon gave journalists and voluntary service agencies the perception that Ottawa focused more on maintaining good relations with Santiago than with resettling refugees. By 20 December, only 184 applicants acquired Canadian visas. Yet, Canadian immigration officials received 1,400 applications. In January 1974, 140 individuals arrived by government chartered aircraft.[21] Throughout 1974, Chilean refugees continued to arrive in small numbers due to more stringent immigration screening than with the Hungarian, Czechoslovak, or Ugandan Asian movements.

Chilean Refugees Begin to Arrive in Canada: The Case of the Durán Family

Among the first Chilean refugees to arrive in Canada were a young professor Claudio Durán, his wife Marcela, their six-year-old daughter, Francisca, and one-year-old son, Andrés. Initially, Claudio Durán went into hiding and moved between his friends’ residences before he and his family found sanctuary at the Canadian embassy in Santiago. Soon after, Canadian diplomatic staff moved sixteen individuals, including the Durán family, to the Canadian ambassador’s residence. Subsequently, a Canadian immigration official flew in to process the group for immigration. They were admitted into Canada under ministerial permits since a specific class for refugees did not exist in Canadian immigration legislation at the time (the later implementation of the 1976 Immigration Act permitted Canadian officials to entrench a humanitarian class for convention refugees, and displaced and persecuted persons). The Durán family was placed on a flight to Montreal, and eventually resettled in Toronto where Claudio Durán later taught philosophy at York University.[22]

In mid-February 1974, the number of Chilean arrivals rose to 275 persons, while another 302 individuals received visas, but were still in transit to Canada. By the end of March, Canadian officials granted 780 visas. Later that spring, over 1,000 refugees reached Canada.[23]

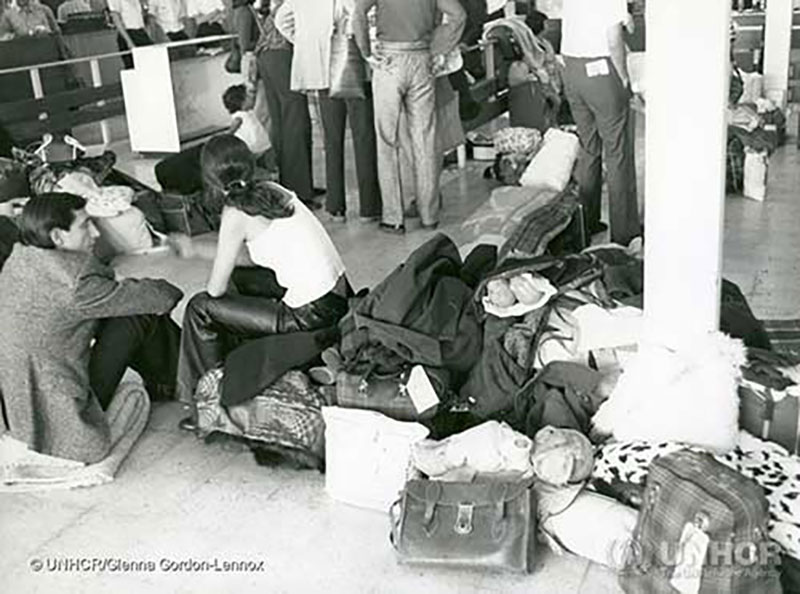

Credit: UNHCR/Glenna Gordon-Lennox

The House of Commons Opposition Criticizes the Government Response

In the House of Commons, the opposition attacked the Liberal government of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau for its slow response to the Chilean crisis. New Democrat MPs Andrew Brewin and John Harney repeatedly asked the government what its response would be.[24] While Minister of Manpower and Immigration, Robert Andras, promised to relax selection criteria, Brewin asked about the specific details, and that the necessary security checks would not result in long delays in bringing the refugees to Canada.[25] By 1974, New Democrat MPs lost faith in the government’s promises to help the Chilean refugees after news broke detailing the treatment received by some of them. New Democrat MP John Rodriguez noted that:

Three common complaints from UN refugee camps have been that the Canadian immigration officials presume the clients to be guilty as criminal terrorists until proven innocent. The refugees also have spoken bitterly of police-type interrogation. Thirdly, the manner in which the Canadian officials have gone about assisting these refugees appears contrary to what the minister of Manpower and Immigration in his statement referred to as humanitarian considerations.[26]

With the Cold War in the background, not all MPs disapproved of the federal government’s perceived inaction. Progressive Conservative MP Ian Arrol wondered why the Canadian government thought “…it necessary to facilitate the entry into this country of these communists.”[27] Social Credit MP Réal Caouette asked “is the [immigration] department considering the advisability of suggesting to Chilean immigrants to go rather to the USSR, Cuba, the People’s Republic of China and Algeria where ideologies would be more in keeping with their deep convictions and yearnings?”[28] Public criticism of the Canadian government’s actions extended to non-governmental organizations, including the Canadian Council of Churches, which noted that it took Canada six to eight months to screen prospective applicants for security reasons. In that time, individuals and families experienced displacement, imprisonment, or death.[29]

Canadian Churches and Voluntary Service Organizations Push Officials for a Faster Response

Public awareness of the Chilean situation grew. In October 1974, a delegation consisting of Amnesty International, Canadian Council of Churches, Canadian Labour Congress, Confederation of National Trade Unions, Canadian University Service, and Anglican, Lutheran, United and Presbyterian churches met with Secretary of State for External Affairs, Alan MacEachen, and the Minister of Manpower and Immigration, Robert Andras. The delegation presented a brief on the Chilean crisis and attempted to convince the Canadian government to more easily admit Chilean refugees to no avail. Despite the efforts of ethnocultural community groups, churches, and humanitarian organizations, the Canadian government moved slowly because of American support for the Pinochet government, and the prospect of permitting hundreds of alleged Marxists to enter Canada.[30]

Various groups in Canada continued to lobby the federal government to implement a special program for the Chilean refugees. The aforementioned groups requested that the Canadian government relax admissions criteria including waiving the points system and permitting 10,000 refugees from Chile to enter Canada.[31] Between the time of the coup d’état and the end of February 1975, 1,188 people received landed status in Canada. Of this group, 1,125 were Chilean nationals, with the remainder comprising 26 other nationalities.[32] Between 1973 and 1978, due in part to pressure from international organizations, university committees, and church and humanitarian groups in Canada, the federal government admitted 6,990 individuals under its special Chilean program.[33]

Credit: UNHCR/Glenna Gordon-Lennox

Credit: UNHCR/Glenna Gordon-Lennox

Conclusion: Nearly 7,000 Chileans Resettled in Canada

The 1973 Chilean coup d’état is an example of sudden Cold War crisis that forced thousands of individuals to flee their homelands for safe haven elsewhere. The Canadian government’s slow response to the plight of Chilean refugees was in stark contrast to earlier refugee resettlement schemes. Due in part to Canadian Cold War ideology, economic interests, and Canada's own trade agreements, the Canadian government was reluctant to intercede despite a desire to maintain its image as a major contributor to international humanitarian initiatives.

Public criticism of the Canadian government’s initial inaction in bringing Chilean refugees to Canada extended to non-governmental organizations which noted that it took Canada six to eight months to screen prospective applicants for security reasons when it took only days and weeks during the Hungarian, Czechoslovak, and Ugandan Asian resettlement schemes. Despite the efforts of ethnocultural community groups, churches, and humanitarian organizations, the Canadian government more cautiously admitted left-leaning refugees fleeing right-wing states, as opposed to refugees fleeing communist regimes like those in Hungary and Czechoslovakia. International observers found Canada’s response to be one of the worst among Western countries in resettling Chilean refugees. Despite this, nearly 7,000 persons were permanently resettled in Canada as part of the special Chilean program.[34]

- Oral History with Ruth Miranda, interviewed by Cassidy Bankson, Victoria, BC, 30 November 2012. Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 (hereafter CMI) Collection (12.11.30RM), 00:28:55.↩

- Harry Diaz, “Chileans,” in Encyclopedia of Canada’s Peoples, ed. Paul Robert Magocsi (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999), 348; Reginald Whitaker, Double Standard: A Secret History of Canadian Immigration (Toronto: Lester and Orpen Dennys, 1987), 256.↩

- Gerald Dirks, Canada’s Refugee Policy: Indifference or Opportunism (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1977), 245.↩

- Francis Peddie, Young, Well-Educated and Adaptable: Chilean Exiles in Ontario and Quebec, 1973-2010 (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2014), 44.↩

- Dirks, Canada’s Refugee Policy, 245; Peddie, Young, Well-Educated and Adaptable, 46-47.↩

- Dirks, Canada’s Refugee Policy, 245.↩

- Library and Archives Canada (hereafter LAC), Goldie Josephy fonds, MG31-I4, vol. 4, file 5 “Canada’s Response to the Chilean Coup, 1974,” paper, “Canada’s Response to the Chilean Coup: Presentation to the Canadian Government - October, 1974,” 3.↩

- Oral History with Michael Molloy, interviewed by Emily Burton, Ottawa, ON, 3 December 2015. CMI Collection (15.12.03MM), 01:04:29.↩

- Oral History with Michael Molloy, 01:10:03.↩

- Ninette Kelley and Michael Trebilcock, The Making of the Mosaic: A History of Canadian Immigration Policy (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010), 367-368.↩

- Dirks, Canada’s Refugee Policy, 246. For further context, see Terence Belford, “Sharp explains soft-pedalling: Churches criticize Canada’s policy on Chile,” Globe and Mail, 4 October 1973, 4.↩

- Freda Hawkins, Canada and Immigration: Public Policy and Public Concern (Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1988), 385.↩

- LAC, Social Science Federation of Canada (hereafter SSFC) fonds, MG28-I81, vol. 419, file 21 “Chilean Refugees - Memo of Nov 15, 1973 to Presidents, Vice-Presidents, Secretary-Treasurers, Executive Officers, 1973-1974,” letter from Donald C. Savage, Executive Secretary, Canadian Association of University Teachers to Hon. Mitchell Sharp, Minister for External Affairs, Ottawa, 25 October 1973, 1.↩

- Letter from Donald C. Savage to Mitchell Sharp, 2. For further context, see David Zimmerman, “‘Narrow-minded people’: Canadian Universities and the Academic Refugee Crises, 1933-1941,” Canadian Historical Review 88.2 (June 2007): 291-315. Between 1933 and 1941, the Canadian academic community was largely unsuccessful in helping refugee academics flee German-occupied Europe.↩

- LAC, SSFC fonds, MG28-I81, vol. 419, file 17 “Chilean Refugees - Memo of Nov 13, 1973 to Heads & Chairmen, Social Sciences Depts. (Canadian Universities),” “Extract from Minutes, SSRCC, October 19, 1973, “Chilean Refugee Scholars,” 1.↩

- Peddie, Young, Well-Educated and Adaptable, 46-47.↩

- Suha Diab, “Fear and (In)Security: The Canadian Government’s Response to the Chilean Refugees,” Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees 31.2 (2015): 53.↩

- Dirks, Canada’s Refugee Policy, 246-247.↩

- Dirks, Canada’s Refugee Policy, 247; Whitaker, Double Standard, 255-261; Hawkins, Canada and Immigration, 385.↩

- Eva Salinas, “How the Chilean coup forever changed Canada’s refugee policies,” Globe and Mail, 6 September 2013 (updated 11 May 2018), accessed 21 June 2019, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/escape-from-chile/article14176379/.↩

- Dirks, Canada’s Refugee Policy, 247-248.↩

- Salinas, “How the Chilean coup forever changed Canada’s refugee policies.”↩

- Dirks, Canada’s Refugee Policy, 248.↩

- “Parliament: Questions,” Globe and Mail, 17 November 1973, 7.↩

- Canada, Parliament, House of Commons Debates, 30 November 1973 (Robert Knight Andras, Liberal), accessed 4 July 2019, https://www.lipad.ca/full/permalink/2891554/; Canada, Parliament, House of Commons Debates, 30 November 1973 (Francis Andrew Brewin, New Democrat), accessed 4 July 2019, https://www.lipad.ca/full/permalink/2891560/.↩

- Canada, Parliament, House of Commons Debates, 8 January 1974 (John R. Rodriguez, New Democrat), accessed 4 July 2019, https://www.lipad.ca/full/permalink/2899787/.↩

- Canada, Parliament, House of Commons Debates, 19 November 1973 (Ian MacLachlan Arrol, Progressive Conservative), accessed 4 July 2019, https://www.lipad.ca/full/permalink/2888040/.↩

- Canada, Parliament, House of Commons Debates, 4 December 1973 (David Réal Caouette, Social Credit), accessed 4 July 2019, https://www.lipad.ca/full/permalink/2892335/.↩

- Kelley and Trebilcock, Making of the Mosaic, 368-369.↩

- Ninette and Trebilcock, Making of the Mosaic, 367-368; Dirks, Canada’s Refugee Policy, 249.↩

- Dirks, Canada’s Refugee Policy, 249-250.↩

- Canada, Parliament, House of Commons Debates: Official Report, First Session – Thirtieth Parliament, Volume 5 (Ottawa, Queen’s Printer and Controller of Stationery, 1975), 4501. The citizenship of the remaining 63 individuals were as follows: Argentina (3); Australia (1), Austria (3); Bolivia (4); Brazil (16); Colombia (1); Czechoslovakia (2); Ecuador (1); France (1); Haiti (1); Hungary (2); India (1); Italy (1); Kenya (1); Mexico (1); Nicaragua (1); Peru (1); Paraguay (1); Poland (1); Tanzania (1); United Kingdom (3); United States (1); Uruguay (8); Vietnam (1); Yugoslavia (5); and Zaire (1). Furthermore, a 1976 Department of Manpower and Immigration report indicates that between September 1973 and February 1976, 5,620 Chileans applied to enter Canada as refugees or as members of an Oppressed Minority – persons who did not meet the eligibility conditions for refugee status under the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. In all, 4,420 individuals received authorization to enter Canada, of which 3,501 had landed, while a further 970 were still in process. See LAC, Immigration Branch fonds, RG 76, vol. 986, file 5781-1 “Chilean Refugees Accepted for Permanent or Temporary Resettlement.”↩

- Kelley and Trebilcock, Making of the Mosaic, 368.↩

- Kelley and Trebilcock, Making of the Mosaic, 368.↩