by Jan Raska, PhD, Historian

Introduction

Over the last several decades, Canada has become increasingly dependent on foreign workers to meet its growing labour shortage. This is particularly evident in the agricultural, service, and homecare industries.[1] The Canadian government regulates all temporary foreign worker programs. Currently, there are two major temporary foreign worker labour programs in Canada. One is the International Mobility Program (IMP) which covers a diverse range of work including: intra-company transfers, youth work exchange programs, research- and studies-related work permits, airline employees, and United States government personnel. The other is the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP). First introduced in 1973 as the Non-Immigrant Employment Authorization Program (NIEAP), it was later renamed to the TFWP.

This paper focuses on the historical recruitment of foreign labour to Canada with an emphasis on domestic workers. Early migrations of domestic workers to Canada were predicated on exclusion from permanent residency. This was largely due to bureaucratic and societal notions of migrant desirability which were preferential to white Europeans over other racialized groups. After the Second World War, however, domestic workers from non-European origins were increasingly welcomed in Canada as the demand for their labour continued to increase. Although bureaucratic and societal biases remained, many of these workers eventually secured a path to permanent residency. Today, the TFWP and one of its streams: the Live-in Caregiver Program (LICP), formerly known as the Domestic Worker Program, is responsible for overseeing work permits and changes in employment. Caregivers can apply for permanent resident status in Canada after completing 24 months of paid employment within a period of four years.

Brief History of Labour Migration in Canada

In early New France, women and men used domestic work as a way to migrate into the colony. Historian Marilyn Barber notes that by the nineteenth century, it became a distinctly female occupation.[2] However, notable exceptions existed. Historian Lorraine C. Brown asserts that in British Columbia, male Chinese workers were hired for domestic service. European settlers soon stereotyped male Chinese domestic workers as “feminine,” “childlike,” and “submissive.” These same settlers also attempted to coerce Chinese domestic workers to supply their labour at wages below market rates.[3]

Although traditionally an unpaid household task, domestic work was later assigned to a paid housekeeper who would be compensated for their service.[4] As historian Eric Sager points out, many female immigrants would have objected to domestic service, if not for the fact that “an obvious path of entry into Canada and its labour markets came with being ‘in service.’” In 1891, female domestic workers comprised 41 percent of all women with occupations. This rate would fall to 18 percent by 1921.[5] With women increasingly utilizing their labour in other employment sectors, the demand for domestic workers remained and employers were forced to look overseas to fill these positions.

Filling the Demand for Early-20th Century Domestic Service: Recruiting Foreign Labour from Overseas

By the turn of the twentieth century, Canadian immigration authorities recruited three classes of immigrants: farmers, agricultural workers, and domestic workers. Immigration officials considered single women, from the British Isles and between the ages of 17 and 35, as desirable immigrants suitable for domestic work in Canada. Before the First World War, 75 percent of immigrant domestic workers arrived from the British Isles.[6]

Despite established bureaucratic notions of immigrant desirability to recruit workers from the British Isles, successive labour schemes were established to bring much-needed foreign labour on a temporary basis, into the country’s economy. Some notable schemes to bring migrant workers to Canada include the admission of 100 Guadeloupian women to Quebec under a Caribbean domestic scheme in 1910-1911.[7] A year later, two Barbadian steelworkers were sent back to the Barbados to recruit steelworkers for the Dominion Iron and Steel Company in Nova Scotia.

Credit: National Parks Service, Ellis Island National Monument, “Women from Guadalupe At Ellis Island on April 6th, 1911”

These migrations of Black temporary labourers were overshadowed by the Canadian government’s passage of Order-in-Council P.C. 1911-1324, banning “any immigrants belonging to the Negro race, which is deemed unsuitable to the climate and requirements of Canada.” While the regulation was passed officially in August 1911, it was repealed soon after. However, the attitudes and practices of exclusion remained until after the Second World War. Historian Steve Schwinghamer asserts that the order-in-council served as “a powerful indication of the government’s desire to prevent Black settlement in Canada.”[8]

The exclusion of non-white labourers from a path to permanent residency or from entering Canada continued throughout the interwar period. A well-known example of this prohibition is the 1923 Chinese Immigration Act, which banned virtually all Chinese immigration to Canada by restricting acceptable categories of Chinese immigrants. It is estimated that only 15 Chinese immigrants entered Canada before the act was repealed in 1947.[9]

Postwar Experiment: Allied Veterans as Temporary Workers in Canada

In 1946 and 1947, federal immigration officials admitted some 4,500 Polish veterans – in fear of repatriation back to Poland which had come under communist control. These former Allied service personnel were obliged to work as farm labourers for a period of one-year upon signing manual-labour contracts. After the successful completion of their labour contracts, the Polish veterans could leave their vulnerable status as temporary workers and apply for permanent residence in Canada. A majority of the veterans later became permanent residents and Canadian citizens. The success of the Polish veterans movement saw the Canadian government expand its resettlement of foreign workers to fill labour gaps in various sectors of the Canadian economy including: agriculture, forestry, mining, construction, and domestic service.

Filling the Demand for Postwar Domestic Service: Recruiting Foreign Labour from Overseas

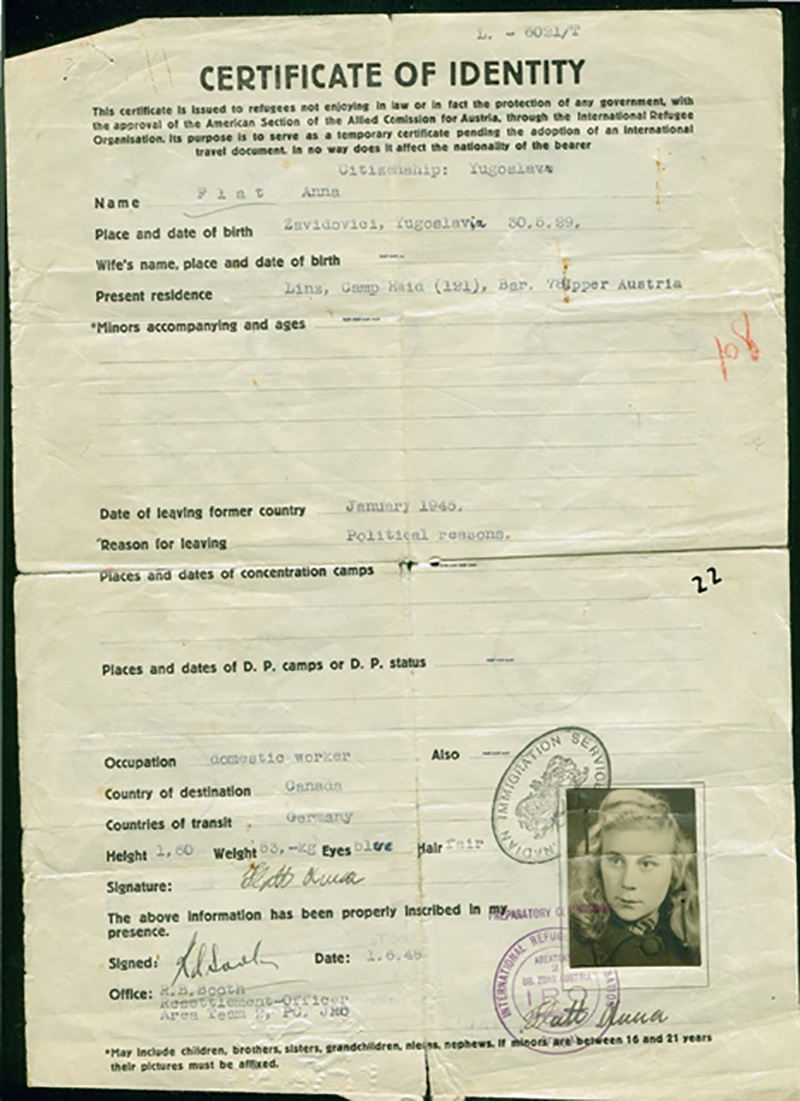

Between 1947 and 1952, the Canadian government welcomed over 186,000 displaced persons and political refugees as part of its Displaced Person (DP) scheme. Displaced persons were obligated to sign one-year manual-labour contracts in various sectors that sought to fill labour shortages, such as those listed above.[10] Unlike the Polish veterans, those who arrived in Canada under the DP movement did so as landed immigrants (i.e. permanent residents). One such example is Anna Marcin (née Flat), a refugee who fled Yugoslavia in January 1946, for political reasons. She resided at the Reid DP camp in Austria before arriving at Pier 21, on board MS Saturnia, in August 1948. Admitted into Canada under the DP movement, Marcin’s International Refugee Organization (IRO) documentation listed her occupation as a “domestic worker.” In reflecting upon her immigration to Canada and her initial employment as a domestic worker, Marcin asserts…

I arrived at Pier 21 as a refugee after the Second World War. I came to work as a domestic and was promised that I would have my own room with my own bed. That never happened. I went to work for a Jewish family in Montreal. I stayed with them for ten months but because the work was so hard the government let me leave before my year long commitment was up. I worked very hard in factories and saved every cent until I could sponsor my family.[11]

Anna Marcin’s immigration story speaks to the vulnerability and precarity that some newcomers employed in domestic service felt shortly after arriving in Canada. Using domestic service as an example, political scientist Abigail Bakan and sociologist Daiva Stasiulis note that Canadian officials attempted to capitalize on the labour potential and vulnerability of East European refugees who were considered less-ethnically desirable than British domestics. Within the DP movement, official preference (ethnic and religious) was given to applicants of Protestant background and to those of Baltic origin.[12]

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (DI2015.504.1)

Recruitment of Mediterranean Domestic Workers to Canada

Bureaucratic preferences aside, under the DP scheme, Canadian officials also provided assisted passage and guaranteed employment to 500 Italian domestic workers. The scheme largely faltered due to cultural, religious, and linguistic differences between the domestic workers and their Canadian employers. Later in the decade, Immigration Branch officials successfully recruited some 7,000 Greek domestic workers, who comprised 25 percent of the total number of Greek immigrants to Canada during the 1950s.[13]

The Greek Civil War (1946-1949) left Greece in ruins, and caused widespread economic distress and political tensions, forcing many Greek workers to leave their homelands for opportunities elsewhere. Constantina Kambouris remembers how Greek society was divided between leftists and nationalists, often leading to life-altering consequences. Her father was killed by Greek compatriots or in her words, “the neighbours,” suggesting that those responsible were people from a nearby village.[14] Kambouris reflects on this difficult period and the decision to seek safety and economic opportunity elsewhere…

That's why I had to leave the country back then. Doesn’t matter if I was reaching Athens, doesn't matter what. Back then, I had to leave the country. I didn't want to see, if I went down to my village, I don't want to see my people, my village people, or the next village people, you know. I could not even see them. When I left for Canada, I didn’t say goodbye to nobody. I went tonight to see my people and left.[15]

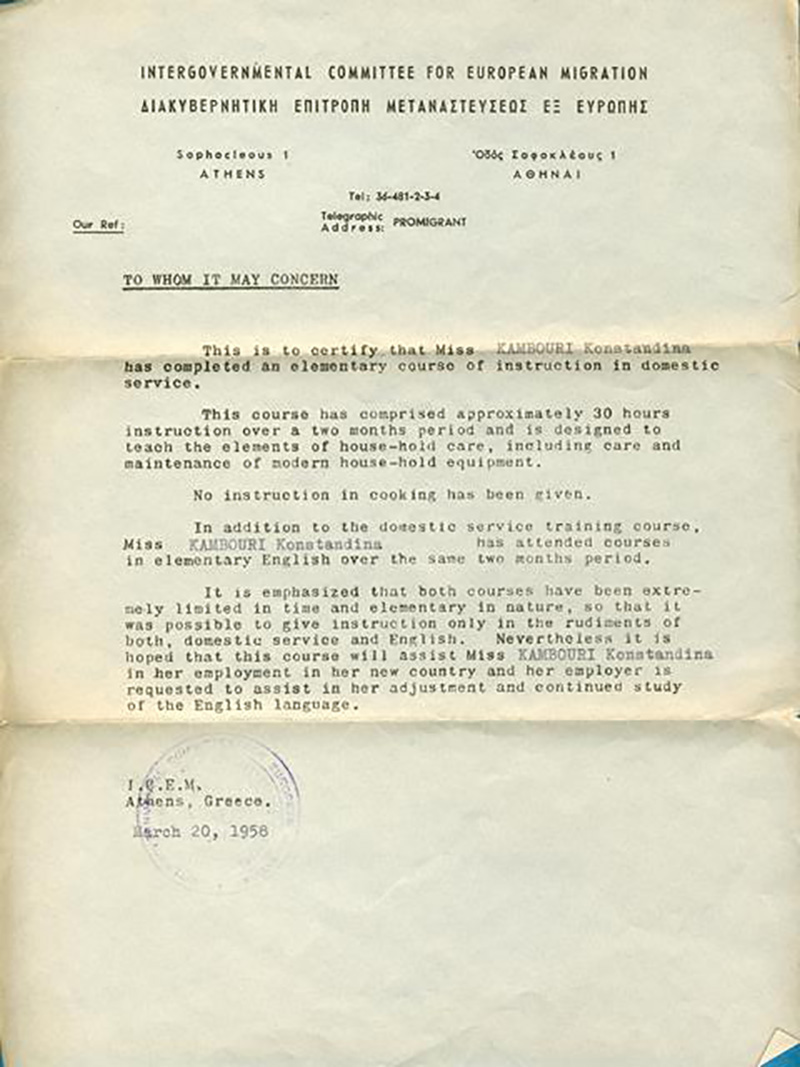

Prospective Greek immigrants, who sought admission into Canada as domestic workers, often brought supporting documentation outlining their training and linguistic ability in order to receive clearance from Greek officials for emigration abroad. This documentation was also used to prove they had the qualifications necessary for domestic work in Canada. For example, in March 1958, the Athens office of the International Committee for European Migration (ICEM) furnished Konstandina [sic.] Kambouri [sic.] with a letter indicating that she had “completed an elementary course of instruction in domestic service.” The course comprised 30 hours of instruction over a two-month period teaching elements of household care, including how to care for modern household equipment. However, the course did not provide instruction in cooking.

Credit: Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (DI2016.9.1)

During that same two-month period, Kambouris also attended a course in elementary English. While the ICEM’s letter emphasized that both courses were “elementary in nature,” it was hoped that the instruction provided would assist Kambouris with her future employment in Canada.[16] In reflecting on her immigration to Canada, Constantina Kambouris recalls…

They took us to Employment Insurance and … from the Employment Insurance people, they had make an application to get us, so, the Jewish lady came with the black Buick, big car. Then she come up and the lady at the Employment Insurance said, “You are very lucky” tell her. And, “You have the best bright girl.” And she told me I'm very lucky also because Mrs. Silver, she is a very nice person to work with … She told me, “No lies, no stealing, and no mouthing.” Then I said to her because I was understanding well English, right. I told her … “I'm raised to not to steal, not to lie.” And she was very happy about it.[17]

Upon arrival in Canada, some domestic workers were expected to meet certain sociocultural ‘norms.’ As in Kambouris’s case above, her employer, a Mrs. Silver, expected Kambouris to conform to her family’s standards surrounding personal conduct.

In the mid-1950s, the continued labour shortage in domestic service across the country pushed federal officials to establish a special movement of migrant workers from the Caribbean.[18] These workers navigated the aforementioned sociocultural ‘norms’ expected of them and their labour, but also the existing ethnocentric biases of federal officials.

Implementing the West Indian Domestic Worker Scheme

In a federal cabinet meeting held in June 1955, Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, Jack Pickersgill, informed his colleagues, who were discussing the implementation of a West Indian domestic worker scheme, that existing immigration regulations restricted immigration from the Caribbean. However, West Indian domestic workers could be permitted to enter the country by means of submission of applications on their behalf by Canadian residents, only if the latter “receive and care for them provided they came within the categories of close relatives or fiancés.” Pickersgill noted that special consideration should be given to individual cases whereby a person had “outstanding qualifications” or whose admission into Canada was warranted on “humanitarian grounds.” The federal cabinet considered the admission of an initial group of 100 Jamaican women to serve as “domestic servants,” on a trial basis, for a period of one year. The scheme was to then be reassessed the following year. Pickersgill noted that this proposal “presented a great many difficulties,” in part because Barbadian officials had first inquired about the possibility of such a labour scheme with Canada.

The Minister of Citizenship and Immigration then recommended that the Canadian government implement an experimental scheme involving 75 domestic workers from Jamaica and 25 from Barbados for a period of one year. Responsibility for the placement of these workers would fall to the Department of Labour. Meanwhile, the domestic workers would be granted landed status (permanent residency) upon arrival in Canada.[19]

The West Indian Domestic Worker Scheme introduced by the Canadian government in 1955 saw immigration officials admit 100 female domestic workers under existing exclusionary immigration policy: candidate domestics had to be single, between 18 and 35 years of age, and in good health. Barbadian and Jamaican officials were responsible for the occupational screening and personal examination of each applicant. Meanwhile, the process of medical screening was left to Canadian authorities. The limited and exclusive scheme was considered a success by Canadian officials as a majority of the domestics remained in their positions although, as historian Donald Avery points out, this was likely because racism excluded them from any other occupation.[20]

Ethnocentric Preferences and Diplomatic Interests: Federal Cabinet Assesses the West Indian Domestic Worker Scheme

At a cabinet meeting in March 1956, Pickersgill claimed that the experimental West Indian domestic worker scheme “had been most successful.” The scheme had driven further demand for domestic workers from the region. The Minister of Citizenship and Immigration then recommended that the scheme be enlarged, with the approval of the Minister of Labour, to include the admission of 200 domestic workers from Jamaica, Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago, and British Guiana. Despite Pickersgill’s recommendation to increase the level of immigration of Caribbean domestic workers, he then went on to indicate his misgivings “over the possible creation of a coloured problem for the future.”[21]

The previous year, federal cabinet members had worried about the temporary entry of Jamaican domestics and the difficulty in establishing “fully effective controls on the movements of these persons.”[22] At the aforementioned March 1956 meeting, cabinet members noted that if a domestic worker returned to the West Indies to marry, then “good reasons would have to be given for excluding them” from coming back. In addition, it was noted that while the existing type of domestic worker had been “very good,” cabinet felt that it was “doubtful if the British West Indies could continue to maintain such as high standard amongst those coming forward for employment. If the quality fell, there would be legitimate reasons for barring entrants and the programme would eventually come to an end.” Yet, given the interest in further improving relations with the West Indies, and with particular emphasis on trade, Pickersgill thought it advisable to proceed with the scheme’s expansion.[23] The scheme’s popularity with domestic workers and governments in the West Indies soon brought further interest from officials in St. Lucia and St. Vincent who wished to have workers from their jurisdictions included.[24]

In the spring of 1959, the federal cabinet approved the annual admission of 250 female domestic workers from the West Indies and 30 from British Guiana. At a cabinet meeting in October 1959, the Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, Ellen Fairclough, considered this movement of available labour to be “desirable” for admission into Canada and brought before her colleagues a proposal to admit these domestic workers during the spring months rather than the fall or winter, as according to Fairclough, the women would have no opportunity to acquire proper clothing for the winter months. The Minister of Citizenship and Immigration then raised concerns over the timing of fall and winter admissions as the women would have to also undergo a three-month training course before moving to Canada.[25]

Bureaucratic Biases Come to the Fore: Cancelling the West Indian Domestic Scheme

The following year, immigration officials, who had earlier touted the West Indian Domestic Scheme as a success, were now considering cancelling the program despite the good performance of the domestic workers themselves. In a May 1960 memorandum, the director of immigration noted with some concern that “these girls, as soon as they are established, are free to apply for the admission of their relatives and fiancés…[who] are likely to be unskilled workers.” Without any evidence to support his claims, the director of immigration claimed that most of the Caribbean fiancés were frauds since illegitimacy was “a fact of life…[and] it is not uncommon for a single girl to have children by 2, 3, or 4 different men.” Historian Donald Avery notes that ethnocentric and biased views, coupled with the Department of Citizenship and Immigration’s emphasis on recruiting highly-educated workers, ultimately led to the termination of the West Indian Domestic Scheme in 1966.[26]

Sociologist Simone A. Brown notes that such biased views of Caribbean workers remained rooted in Immigration bureaucracy decades after the conclusion of the West Indian Domestic Scheme. In Mavis Baker v. Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, the Supreme Court of Canada concluded that the Immigration officer’s notes in the case, described Baker in terms of immorality, illegitimacy, and undesirability “…and the manner in which they are written, do not disclose the existence of an open mind or a weighing of the particular circumstances of the case free of stereotypes…” Mavis Baker arrived in Canada from Jamaica on a visitor’s visa in 1981. She later worked as a live-in domestic worker, and gave birth to four children. Unable to work because of a diagnosis of schizophrenia, she later applied for social assistance in 1992. Baker’s application alerted Canadian immigration authorities to her “illegal” status in Canada, and she was later ordered deported. No reason for the deportation order was given. Baker then applied for a judicial review of her case which culminated with the Supreme Court of Canada’s ruling in July 1999, that her application for permanent residency should be considered.[27]

Despite the ethnocultural biases and preferences of some Immigration officials, during its years of operation, the West Indian Domestic Scheme brought some 3,000 women to work in Canada.[28] In 1967, the federal cabinet implemented Order-in-Council P.C. 1967-1616, commonly referred to as the points system, which further liberalized Canadian immigration policy and led to significant immigrant admissions without ethnocultural or geographic restrictions.

The West Indian Domestic Scheme was later reintroduced in 1973, albeit under different conditions. Domestic workers from the Caribbean region were admitted into Canada under a new temporary employment authorization program (i.e. the Non-Immigrant Employment Authorization Program (NIEAP)). These same domestic workers could only remain in the country if they kept their positions. The changing of jobs or employers could result in deportation.[29] Less than a decade later, the Canadian government expanded its scheme for temporary domestic workers as demand continued to increase.

From Foreign Domestics to the Live-In Caregivers

In 1981, the Foreign Domestic Movement Program was established to help fill temporary employment positions for the care of children, elderly family members, or family members with disabilities. In 1992, the scheme was reintroduced as the Live-In Caregiver Program (LICP) to address the lack of live-in caregivers in Canada. Today, the program is now dominated by caregivers from the Philippines. One such example is Liza R. Bautista. In order to support her siblings and her parents who had become ill, Bautista obtained employment in Hong Kong as a domestic worker before coming to Canada in November 1991. Below, she reflects on her journey to Canada as a domestic worker/caregiver from the Philippines…

So I found an employer, and it was taking care of two kids. And they were ages two and four years old at the time. And I was their, I was their nanny. And it was, you know, being in the Live-In Caregiver program has advantage, because the promise of permanent residency. But while you are in that program, you’re still considered temporary. It’s still under the banner of the temporary foreign worker program. And so there’s a lot of limitations. So you have the systemic issue of having a lot of limitations within that immigration program. So you cannot go to school, you are not allowed to access a lot of social services.

And there’s also the, the issue of … it’s considered a lowly profession in Canada. So there’s that internalized oppression in you, that you are not valued. And there’s a lot of things that does to your self esteem. Maybe imagined, but also very true in a lot of the instances. So I, but at least you can volunteer. You can take some ESL courses. And there’s no, nothing to stop you from dreaming that you can achieve a profession or another career that you want. Once you have that paper that you’re [a] permanent resident in Canada.[30]

Liza Bautista’s lived experience points to the restrictions domestic workers/caregivers face with regards to their immigration status and issues around employment precarity and socioeconomic status, among others. Despite these earlier barriers, she was successful in obtaining gainful employment with a settlement agency, the Immigrant Services Society of BC (ISSofBC).

Credit: Oral History 18.11.02LRB with Liza R. Bautista, 2 November 2018. Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection

Sociologist Rina Cohen notes that domestic workers/caregivers are often confronted with stressful familial situations including working long hours, seven days per week, and feeling as though they have not paid enough attention to close relatives or sent enough money back home to their loved ones. While a common tension within caregiving families is insufficient income, years of loneliness and separation prior to family reunification can also impact a caregiver’s relationships often leading to affairs, estrangement, or even divorce.[31]

Caregivers live in their employers’ homes, and due to isolation, are often unable to exercise their rights under provincial and territorial labour laws. This has led to many caregivers having difficulty measuring their overtime hours in a deregulated and invisible environment. Workers in the LICP can apply for permanent resident status in Canada after completing 24 months of paid employment within a period of four years.[32] In 2014, the federal government lifted the requirement for immigrant caregivers to live with their employer in order to qualify for permanent residence in Canada. The caregiver program was also split into two streams: one for the care of children and the other for the care of individuals with significant medical needs.[33]

Conclusion

In Canada’s immigration past, the use of temporary programs to fill much-needed labour gaps in the Canadian economy depended on what officials deemed desirable as a potential immigrant. Temporary programs were often established by Canadian officials to meet economic needs and diplomatic interests, while using temporary foreign labour that did not meet official notions of a ‘desirable’ immigrant. In some of the movements noted above, migrant workers were admitted into Canada as temporary foreign workers excluded from a path to permanent residency and the possibility of Canadian citizenship.

In the early twentieth century, Canadian immigration authorities excluded racialized migrants from permanent residency, but sought to admit them on a temporary basis for their labour. For others, such as those who arrived under the DP scheme, their admission and landed immigrant status (i.e. permanent residency) were predicated on accepting employment in a sector in need of available labour, such as domestic work, agriculture, forestry, and mining. Other migrants, such as the Polish veterans, arrived in Canada with their residence status predicated on the successful completion of a manual-labour contract. Although considered ‘desirable’ for resettlement in Canada, migrant workers of European origin were often welcomed in varying degrees as evidenced above with some receiving landed immigrant status after completing their contracts, while others were deemed to be in high demand and were given permanent residency upon landing in Canada.

Prior to the implementation of the points system in 1967, foreign worker schemes were often subject to the ethnocentric biases and bureaucratic interests of the federal cabinet and Canadian immigration officials who restricted the admission of foreign workers, such as caregivers, based on ethnocultural background, geographic origin, and economic and diplomatic interests. The liberalization of Canadian immigration policy in the late 1960s removed the last vestiges of racial and geographic discrimination from immigration regulations and practice, placing further emphasis on the educational, occupational, and experiential background of prospective immigrant workers. Today, the Live-In Caregiver Program admits workers from around the world and offers the potential for permanent residency in Canada.

- For example, the Conference Board of Canada estimates that Canada’s labour shortage in the agricultural sector will reach some 113,000 individuals by 2025. See Michael Burt and Robert Meyer-Robinson, “Sowing the Seeds of Growth: Temporary Foreign Workers in Agriculture,” The Conference Board of Canada, 1 December 2016, https://www.cfa-fca.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/8363_SowingtheSeeds-BR.pdf.↩

- Marilyn Barber, “Domestic Service (Caregiving) in Canada,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, last edited 17 June 2021, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/domestic-service. For further context, see Marilyn Barber, Immigrant Domestic Servants in Canada (Ottawa: Canadian Historical Association, 1991).↩

- Lorraine Cecilia Brown, “Domestic Service in British Columbia, 1850-1914,” (M.A. thesis, University of Victoria, 1995), 72.↩

- Barber, “Domestic Service (Caregiving) in Canada.”↩

- Eric W. Sager, “The Transformation of the Canadian Domestic Servant, 1871-1931,” Social Science History 31.4 (Winter 2007): 509, 513.↩

- “Immigrants to Canada, Porters and Domestics, 1899-1949,” Library and Archives Canada, https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/immigration/immigration-records/porters-domestics-1899-1949/Pages/introduction.aspx.↩

- For further context, see “Guadeloupe women [1911]” in Louis Takács, “LET ME GET YOU THERE: Visualizing Immigrants, Transnational Migrants & U.S. Citizens Abroad, 1904-1925,” Alliance for Networking Visual Culture, https://scalar.usc.edu/works/let-me-get-there/guadeloupe-women-1911.↩

- Steve Schwinghamer, “The Colour Bar at the Canadian Border: Black American Farmers,” Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 (hereafter CMI), https://pier21.ca/research/immigration-history/black-american-farmers.↩

- Lindsay Van Dyk, “Chinese Immigration Act, 1923,” CMI, https://pier21.ca/research/immigration-history/chinese-immigration-act-1923.↩

- For further context, see Canadian Council for Refugees, “A hundred years of immigration to Canada 1900-1999,” May 2000, https://ccrweb.ca/en/hundred-years-immigration-canada-1900-1999.↩

- Immigration Story of Anna Marcin (née Flat), CMI Collection (S2012.1187.1).↩

- Abigail B. Bakan and Daiva Stasiulis, “Foreign Domestic Worker Policy in Canada,” in Not One of the Family: Foreign Domestic Workers in Canada, ed. Abigail B. Bakan and Daiva Stasiulis (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997), 33.↩

- Donald H. Avery, Reluctant Host: Canada’s Response to Immigrant Workers, 1896- 1994 (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1995), 208.↩

- Oral History with Constantina Kambouris, interviewed by Cassidy Bankson, Halifax, NS, 14 August 2008, CMI Collection (08.08.14CK), 01:15:06.↩

- Oral History with Constantina Kambouris, 01:15:22.↩

- Letter sent on behalf of Konstandina [sic.] Kambouri [sic.], 20 March 1958, CMI Collection (DI2016.9.1).↩

- Oral History with Constantina Kambouris, 00:03:28; 00:13:20; 00:20:06; 00:21:49.↩

- Bakan and Stasiulis, “Foreign Domestic Worker Policy in Canada,” 33.↩

- Library and Archives Canada (hereafter LAC), Privacy Council Office (hereafter PCO) fonds, RG 2, Series A-5-a, vol. 2658, file “Cabinet Conclusions,” item 14423, title “Immigration; admission of British West Indians for domestic service,” 8 June 1955, reel T-12184.↩

- Avery, Reluctant Host, 209.↩

- LAC, PCO fonds, RG 2, Series A-5-a, vol. 5775, file “Cabinet Conclusions,” item 14995, title “Immigration; admission of coloured domestics,” 29 March 1956, reel T-12185.↩

- LAC, PCO fonds, RG 2, Series A-5-a, vol. 5775, file “Cabinet Conclusions,” item 14344, title “Immigration; admission of domestics from Jamaica,” 6 May 1955, reel T-12184.↩

- LAC, PCO fonds, RG 2, Series A-5-a, vol. 5775, file “Cabinet Conclusions,” item 14995, title “Immigration; admission of coloured domestics,” 29 March 1956, reel T-12185.↩

- LAC, PCO fonds, RG 2, Series A-5-a, vol. 1892, file “Cabinet Conclusions,” item 15763, title “Immigration; admission of coloured domestics from British West Indies,” 14 March 1957. In March 1957, federal cabinet approved a recommendation from the Minister of Citizenship and Immigration and the Minister of Labour to increase the number of domestic workers in the scheme to 230 individuals (during 1957); 100 from Jamaica, 40 from Barbados, 30 from Trinidad, 30 from British Guiana, 15 from St. Lucia, and 15 from St. Vincent.↩

- LAC, PCO fonds, RG 2, Series A-5-a, vol. 2745, file “Cabinet Conclusions,” item 18906, title “Admission of domestics from West Indies,” 8 October 1959.↩

- Avery, Reluctant Host, 209.↩

- Simone A. Brown, “Of ‘Passport Babies’ and ‘Border Control’: The Case of Mavis Baker v. Minister of Citizenship and Immigration,” Atlantis, 26.2 (Spring/Summer 2002): 102-103.↩

- Parks Canada, “West Indian Domestic Scheme (1955-1967) National Historic Event,” https://parks.canada.ca/culture/designation/evenement-event/domestiques-domestic.↩

- Avery, Reluctant Host, 209.↩

- Oral History with Liza R. Bautista, interviewed by Emily Burton, Burnaby, BC, 2 November 2018, Canadian Museum of Immigration Collection (18.11.02LRB), 00:55:10.↩

- Rina Cohen, “‘Mom is a Stranger’: The Negative Impact of Immigration Policies on the Family Life of Filipina Domestic Workers,” Canadian Ethnic Studies/Études éthniques au Canada 32.3 (2000): 83-84.↩

- Kachulis and Perez-Leclerc, “Temporary Foreign Workers in Canada,” i, 5-8; Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (hereafter IRCC), Facts and Figures 2016: Immigration Overview – Temporary Residents (Ottawa: Citizenship and Immigration Canada, 2016), 4-5. Molnar, “Canada’s Temporary Foreign Worker Programs.”↩

- Barber, “Domestic Service (Caregiving) in Canada;” Kachulis and Perez-Leclerc, “Temporary Foreign Workers in Canada.” See page 7.↩