Attention history nerds: Clear your next several hours. There are thousands of years of history to learn about on the Museum’s new digital timeline!

The timeline is full of information about the histories of peoples in the lands we now know as Canada, and presented in a way you won’t find anywhere else.

Discover landmark moments in the history of the settlers and immigrants who arrived, the forces and laws that have shaped those movements, and the history of Indigenous peoples in the territory now known as Canada.

History is not a single, straight line.

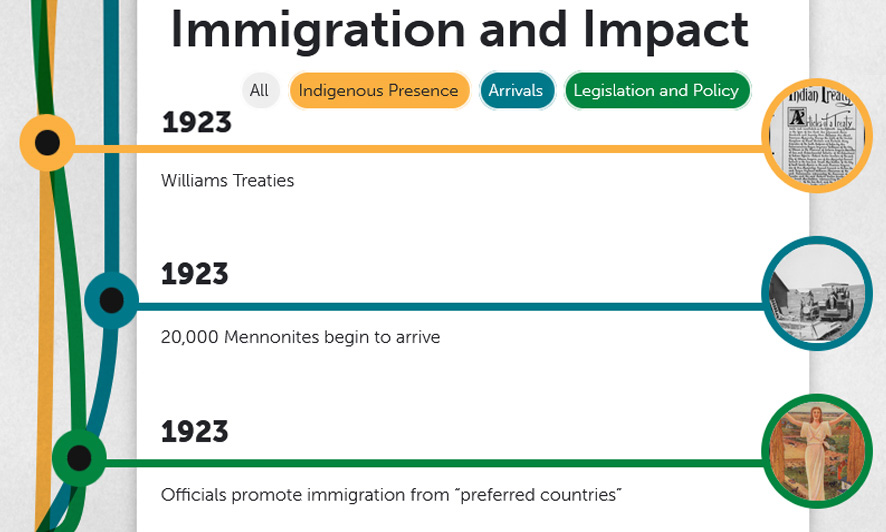

There are many perspectives on the past. That’s why our timeline is made up of three different timeline threads, which we call lenses.

“It made sense to divide the information into lenses,” says Museum historian Jan Raska, who served as principal writer for the non-Indigenous content of the timeline. “We wanted timeline visitors to [be able to] explore the individual timelines within the broader timeline”

Users can view one lens at a time or all at once to see how one timeline relates to the others.

Indigenous Presence

This lens looks at the enduring presence, from time immemorial to today, of Indigenous peoples in the territories we now know as Canada. Covering the longest historical span by far, the entries in this timeline were created by Dr. Daniel Sims, Associate Professor, First Nations Studies at the University of Northern British Columbia, working with a team of Indigenous scholars and knowledge keepers from across the country. It includes archeological evidence of human presence as early as 38,000 BCE at Van Tat (Old Crow Flats) in present-day Yukon, and takes us all the way to today. We learn about the history of confederacies between Indigenous nations, the impact of colonization and settlement in different parts of the country, and landmark legal cases in the fight for land restitution and treaty rights.

Arrivals

The arrivals lens is about the history of people coming to these lands, beginning with the temporary settlement of Vikings in Newfoundland 1000 years ago, all the way up to the 300,000 refugees that have arrived since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. It also marks the arrival of a selection of notable individuals like brewer John Molson (arrived from England, 1782) Manzo Nagano, the first known immigrant from Japan (arrived 1877), and former cabinet member Jean Augustine (arrived from Grenada, 1960), the first Black woman to hold a seat in Canadian Parliament.

Legislation and Policy

Law, policies and regulations have had a huge impact on who is encouraged to come to this land and who is allowed to stay. This lens begins with the so-called “Doctrine of Discovery”, which gave an ideological framework for colonialism by telling European rulers they could claim dominion over lands they had “discovered” if their inhabitants were not “civilized,” and milestone shifts like the 1976 Immigration Act, which allowed groups of five individuals to privately sponsor refugees - the first such policy in the world. This lens is devoted to the law, policies and regulations that have shaped human movement to, and sometimes from, these lands.

An important new resource

Lisa Prosper, a Whitehorse-based consultant who served as Advisor and Liaison for Indigenous Content on the project, calls the timeline “a great resource from an educational point of view, that hopefully will be taken up by educators and researchers.”

“As we negotiate this shared space that we're trying to develop - this nation-to-nation discourse, this idea of reconciliation - we're all trying to feel our way forward. One of the myths to dispel is the historicization of Indigenous peoples - speaking about Indigenous peoples in the past. This project indicates that those timelines are together through to the present. As the timelines in this project indicate, Indigenous peoples have been an integral part of this story through to the present, and will continue to be into the future.”

“History is important to our futures, in terms of getting to a place where there is a healthier relationship between the crown and Indigenous peoples and Canadians across the country. Education is going to be the way out of that. It's a super important resource because it targets a general public and it's in a format that's digestible and compelling.”