By guest contributor John Moses, Delaware & Upper Mohawk bands, Six Nations of the Grand River Territory, and Director, Repatriation and Indigenous Relations at the Canadian Museum of History

Departures

During parts of its history, Pier 21 was as much a point of departure as it was a destination. As a member of the Delaware and Upper Mohawk bands from the Six Nations of the Grand River Territory near Brantford, Ontario, and as a Six Nations veteran and community knowledge holder myself, I have been fortunate to become heir to the wartime letters and other ephemera of my relative, the late Jesse Moses. A Six Nations Delaware band member, he served with the 11th Canadian Armoured Regiment (the Ontario Tanks) throughout the Second World War. I am pleased to share aspects of Jesse’s wartime service on the occasion of Remembrance Week 2022. My point in so doing is to encourage readers to consider Indigenous contributions to Canada’s military heritage and history in perhaps greater depth than they have done previously; and thus in this sense to begin viewing Pier 21, at least symbolically, as much a point of departure for a discussion of Indigenous military service as it has been a destination for newly arrived immigrants to these shores.

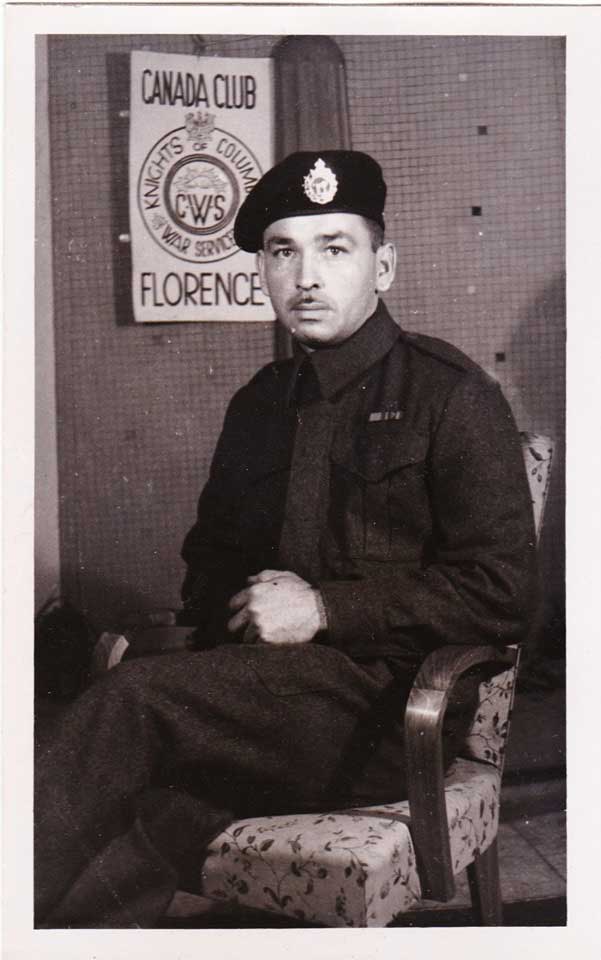

Historical evidence records five troopships with Canadian soldiers aboard departing Halifax's Pier 21 on June 21, 1941. Trooper Jesse Moses, a member of the Delaware band at the Six Nations of the Grand River Territory at Brantford, Ontario was embarked in one of these, the Pasteur.[1] He proudly wore the distinctive black beret with brass cap badge of the 11th Canadian Armoured Regiment - the Ontario Tanks ("the ONTARS") - featuring the unique emblem of an Ontario wildcat ready to pounce. A second cousin of mine, Jesse had been a farm labourer on the family acreage on the Six Nations reserve near Brantford, Ontario, when the war began and was being readied to succeed his father in running the farm when the time came. Young and physically fit, he enlisted soon after the outbreak of the Second World War, as so many other Six Nations band members were doing and had done a quarter-century prior during the Great War.[2]

Indeed, his service is just one manifestation of a political relationship dating from earliest colonial encounters that still endures today in the spirit and intent of the Covenant Chain wampum belt: mutually beneficial diplomatic and trade relations in peace, and military alliance during war. Many Six Nations extended families and individuals were willing to support the notion of a strong and united Dominion and Commonwealth - so long as the Crown respected inherent Indigenous rights in return.

Destinations

Before enlisting, Jesse would have had neither opportunity nor occasion to venture much beyond the limits of the Six Nations reserve. Travelling to Oshawa where the ONTARS were garrisoned and later to the Armoured Fighting Vehicles Schools at Petawawa and Borden would have been adventure enough. By June 1941, however, the ONTARS were ready to ship overseas, destination the United Kingdom. There, they would undertake further training before finally joining combat for the first time in Sicily. The ONTARS would fight throughout the Italian campaign and later northwest Europe, including the liberation of Belgium and Holland. Jesse was finally repatriated home from the Netherlands in the autumn of 1945.

Correspondence

Jesse's service with the ONTARS included the battles of Monte Cassino and Ortona in the Italian campaign, and Arnhem during the liberation of Holland. However, his letters home, subject to strict wartime censorship rules, are nearly devoid of any technical or operational details to interest the military historian today. Jesse's service medals were truly well-earned. But the vagueness of details about his service is understandable given who he was writing to. Jesse’s primary correspondent was his betrothed, Olive, and he wanted to encourage and support her during their forced separation and not worry her. Thus, the content of Jesse’s letters home to Olive largely has to do with tiny snapshots of daily life: the quality (or not) of the food and lodging and, here and there, incidents of humour and irony.

Concerning his departure from Halifax's Pier 21 and the voyage overseas, Jesse's letter to Olive dated England, July 2, 1941, reveals the following:

“This letter is coming from somewhere in England, and I mean somewhere, because if they turned me loose, I wouldn’t know which way to go to get out. This is our third day in England, that is since we landed. We have been in two countries though, England and Scotland … Gee, I could write a book about that trip across, if a fellow could tell all he saw, but they say it’s against the rules to mention nations and so on … I was going to write before we left Canada, but they would have held our letters until we had reached England … That ocean trip is one I’ll never forget. I never dreamed that there could be so much water … When we landed in Scotland, we had to stay on the boat for a whole day … We saw them put up and take down the balloons, and not the kind you buy at the fairs. Most likely you have read about these old castles. We passed about six of them on our train ride from Scotland to England.” (England, July 2, 1941).

By the end of the following month, the ONTARS were well into more specialized training—which did not always proceed smoothly, as Jesse's letter dated August 22, 1941 hints:

"Yesterday we went on a loading scheme. We went down to the station to learn how to load tanks on a train. They have a lot of stone walls along roads over here. Now they have one less."

By 1944 Jesse and the ONTARS were battle-hardened, having fought through the battles of Monte Cassino and Ortona. His letter dated January 9, 1944 was written in the days following the fighting at Ortona and is the most descriptive he gets in writing back home to Olive on the Six Nations reserve:

“I’ll bet my letters have dropped off considerably in the last month. There is only one reason for that. Old Jerry was seeing to it that we didn’t have time to write … Right now we are having a rest period … I could go on and tell you a lot of stories of what we did and saw. But what’s the use. All I can say is that we have seen war at its worst. For being in tight corners our crew has had its fill. So much for the war end of it … We have been practically living in our jalopies. It is surprising what good kitchenettes they make … We spent the most hectic New Year’s Eve that I ever spent, and I hope never to spend again. It was raining like sin and we were sitting about fifty yards from old Jerry’s lines. When we would get out we would sink half way to our knees in mud. What a time we had.”

Returns

Despite an absence of operational detail, Jesse's letters home are invaluable in that they provide insight into the daily round and the thoughts and feelings of a young Indigenous serviceman from Canada who was in the thick of things overseas during wartime. They also bear witness in microcosm to the military service tradition of the Six Nations Confederacy of Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) and other allied First Nations, including the Delaware band of which the Moses family at Six Nations are members, in support of the Crown. Jesse's outward-bound trip thus reveals the history of Pier 21 not only as a destination but as a point of departure for considering other matters, including Indigenous contributions to Canada’s military effort during the Second World War.

- See Rod Henderson, 2016, Fidelus et Paratus: A History of the Ontario Regiment (RCAC), 1866-2016, p. 119

- Two of Jesse’s uncles, Jim Moses and Arnold Moses, had served successively in Canada's two largely Indigenous formations of the Great War, the 107th "Timber Wolf" Battalion, CEF; and the 114th Battalion, "Brock's Rangers". Arnold survived the War as a sapper in the Canadian Engineers and would go on to serve a term as the Six Nations band council elected chief in the the 1950s. Arnold's elder brother Jim, who was recruited as one of the 114th and later 107th's commissioned officers, transferred to the fledgling Royal Air Force and was reported Missing, later confirmed Killed in Action, on April 1, 1918 while serving as air gunner and forward artillery observer with 57 Squadron Royal Air Force, crewing in two-seater DH-4 day bombers.