By Anthony Black, Senior Writer

Published on 01/03/2022

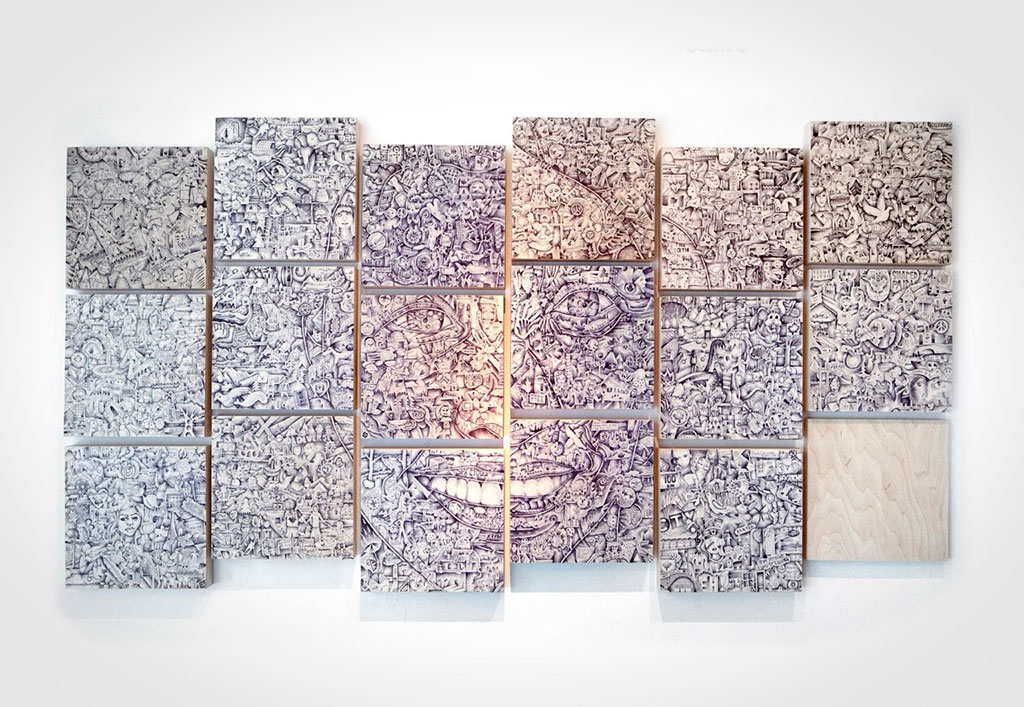

March 4, 2022 was the unveiling of a new art project by the Museum’s Artist-in-Residence, Aquil Virani. Read what he has to say about what makes a hero, what makes for an ideal immigrant, and his hopes for the future.

Your project is called “Our Immigrant Stories.” How would you describe it?

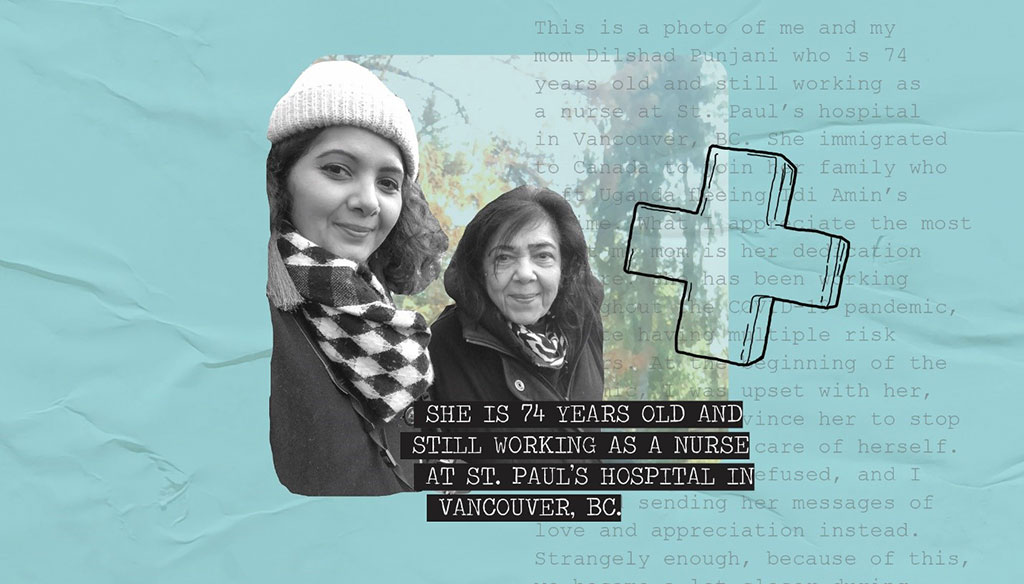

It’s an art project that asks you, “who is an immigrant hero in your life?” I tried to create an occasion for us to take a moment, to actually write it down, and to voice our appreciation for others.

Participants were asked to write down stories, submit photos – I left it quite open. Once people submitted their work (in whatever format) my goal was to present the submissions as they are, and then integrate them into an art project where you see the individual submissions, but also experience the overall artwork as a whole. Sometimes the writing of the initial submission turned into visual art. Sometimes photography turned into animation. My role was to find a way to amplify the stories of others in a creative way, as a kind of mediating megaphone or a conductor of the choir.

How did the residency come about?

I had the privilege of sharing some of my previous art projects at the Museum in 2016 (the Canada's Self-Portrait project). But even before then, I've always kept an eye on the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 because the museum deals with a lot of the things that I'm interested in, both as an artist and as a person. The residency’s virtual element allowed me to apply while living in Toronto or Tkaronto (the Kanien’keha word for “the place in the water where the trees are standing.”)

What are the overlaps between what the Museum does and your interests?

I am proudly the son of two immigrants to Canada: my father is an Ismaili Muslim of Indian origin, born in Tanzania in east Africa; my mom is a French woman, an early childhood educator, now retired, from Beauvais, north of Paris. My parents moved to Vancouver in the 1970s. That's where my interest in immigration comes from: my own heritage and the link between migration and identity.

There's a sense of pride I have, being the son of two immigrants to Canada. I want to help tell their story (and my story) and to adapt it in some way for an audience that's more like me – that was born in Canada. That’s why I connect with the Museum's mandate and the work that the Museum does. There’s also an affinity I have for real stories. I have a drive to document things as I get older, to write things down, to take photos of everything.

Your work blurs the line between art and activism. Can you talk about activism in the context of this project?

Activism for me is a broad umbrella term for the ways in which we can build a better world in an active way, in a deliberate way. This project is a form of activism because I see storytelling, especially about immigrant stories, as fitting into a larger landscape of systemic change.

Systemic issues can feel overwhelming because of their scope. But I ask myself, “what can I do today? What are the tools available to me in this moment?” I view the act of telling my story, the act of sharing and amplifying and uplifting others' stories, as a form of activism. It can be hard to see all of the ripple effects of our actions. But I can tell you with confidence that sharing our immigrant stories builds empathy. And empathy is one of the things lacking in some of the political views in our country.

The request for immigrant hero stories says, “the work is going to celebrate the achievements, big and small, of those who've immigrated to this land.” Why is it important to focus on both big and small stories?

Our social norms suggest that the person who wins at the Olympics deserves to be celebrated, but the janitorial service worker who wipes the floors every evening doesn’t merit the TV spotlight. We have a way of internalizing who gets to be seen and celebrated without actually questioning why. I wrote “big or small” so that everyone would feel welcome to share their story, whether they see it as inspiring or not. So that they would feel valued. There is something lost when we only hear the stories of certain people. It’s not the whole picture.

In the past, Canada's immigration policies have coalesced around ideas of an idealized immigrant. Do you have a sense that Canada today has an idealized immigrant?

Yes. Part of the issue is that politicians feel pressure to “make the business case” for immigration. When a politician says “we should accept immigrants because it's the right thing to do and because they help us build our economy,” critics start to evaluate immigrants based on their contributions – this is a very misguided and dangerous thing to do. I don't agree with the lens of evaluating immigrants based on their economic contribution. People are people.

A lot of the discourse around immigration should be anchored on the understanding that someone is taking a big risk to set up a new life in a new country. There's likely a very good reason – fleeing a war-torn country, or a jeopardized livelihood brought about by social issues or climate change, for example. Our hands are not clean either; we cannot ignore the cascading effects of our own government’s participation in the exploitation, extraction, and colonial intervention in foreign lands all over the world – especially in what-is-called the “Global South.”

Your work feels hopeful and aspirational. What are your hopes for this project and for the future of Canada?

I will admit that I feel overwhelmed by the issues facing Canada and the world sometimes, but we have to start somewhere. In a lot of my projects, I try to create bite-size actions for people to do as an access point into building a better world.

I have a lot of hopes for the future. I hope that the future of the world involves people of different backgrounds coming together more than ever for very honest and safe conversations. I hope that my Muslim family [and] communities can feel safer walking down the street. I hope that settlers, including newer immigrants, can ask themselves hard questions about their role in reconciliation, in reparations, in a meaningful and resource-based contribution to “righting historical wrongs”. I hope that we don't lose a sense of optimism about how we can improve the world by starting small and being honest with ourselves about the consequences of our actions. I hope politicians will find enough courage to hold corporations accountable. I hope that future generations of settlers can appreciate the sacrifices of their immigrant heroes in the past.

Is there anything else that you want to talk about?

I strive to make work that is inclusive and accessible, but that comes with harder questions about who this project involves and who it doesn't involve – working folks with minimal leisure time might not participate, nor families with traumatic stories that feel too raw to share. It's important for us as artists, storytellers and cultural institutions [to ask] which groups of people are not included and what solutions might make our work more inclusive.

I'm also thinking a lot about how the story of immigration interacts with the story of reconciliation and that of Indigenous peoples. How do we celebrate the sacrifices of our immigrant heroes in our personal lives while acknowledging how these stories fit into the colonial project? These are hard questions as we find ourselves in an imperfect reality, trying to sort out the mess. These conversations are difficult, sure, but absolutely essential.

See more of Aquil Virani’s work at aquil.ca.