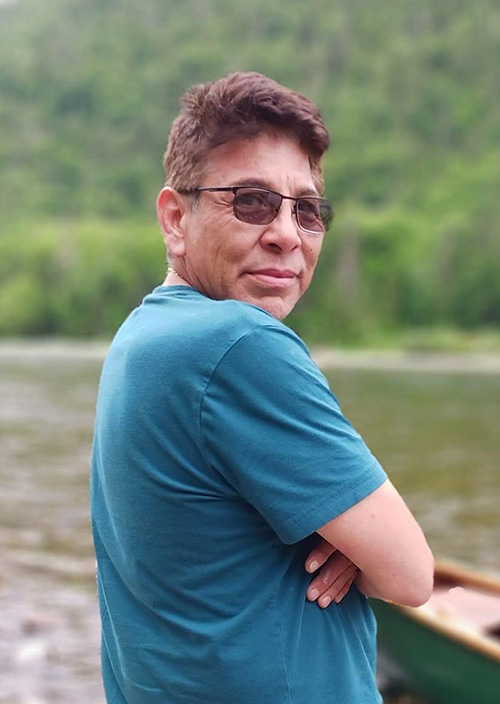

“I don't consider myself a basket maker”

An interview with artist-in-residence Virick Francis about art-making, finding solutions and what it means to be welcomed by Mi’kmaq.

When did you start weaving?

In my early teens, I was making big baskets with my mom. I never made baskets on my own till I was like 17, 18, living in Maine. There was really limited income, living in Maine. All you had was either work for farmers or baskets because black ash is abundant everywhere in Maine.

I was trying to bring back some ash last year through the border. The restrictions are really magnified at the border now because of the ash-boring beetle. Even though I told them the beetle doesn't recognize borders. I would love to get wood transported from Maine to here because it's part of our natural territory.

Can you tell me about the tradition of weaving in Mi’kmaw culture?

Back far as I remember, on reserves or in nearby Mi’kmaw communities, there were more people making baskets as a source of supplementing their income. There was a lot of poverty back then. So they would make baskets and they would go peddle them.

When I was a child, my grandmother and my mom would take a box of baskets and go peddle them in Margaree, Arichat and throughout Cape Breton.

What makes your work different?

I figured anybody can make actually a big basket, so I started focusing on small baskets. I started focusing on making them smaller and smaller. I used to fool kids and tell them I microwaved the big ones and made them small.

The smallest I've ever made fits inside Queen Elizabeth's head on a dime. I can make a miniature tea set that’s two inches by one inch. A tray with cups and saucers. On average, I make smaller baskets faster and easier than I would make bigger ones.

These days I don't even consider myself a basket maker. I'm more leaning toward it as an artist. I'd like to make more pieces of art or something different each time.

During your residency, you’ll be weaving the life cycle of the salmon. Why have you chosen that subject and how are you approaching it?

The salmon is very important to the Mi’kmaq. I plan on starting out with the eggs and then the different components: As an egg grows, as a fish grows, smolts, all different levels, and finishes off with the full-grown salmon.

I want to paint one side as they are and leave the opposite side natural, all in ash. And I want to incorporate spruce gum too so everything will be all natural. I want to incorporate a river and I might even include other species of fish. I was thinking about making eels and trout to be part of the display.

Will you be working in a small scale?

It's going to be a life scale. The full-grown salmon will be three to four feet.

What else does your residency consist of?

I’m going to [teach] some classes at the Museum. And I've been talking with the UINR (Unama'ki Institute of Natural Resources) in Cape Breton here. We are brainstorming about incorporating a visual display with a TV monitor about the history of the Mi’kmaq, the salmon, and incorporating lnuita’simk and two-eyed seeing.

In Mi’kmaw, lnuita’simk is thinking in a different way: There's more than one answer to a question. That's how I teach baskets and how I make them. When people ask me if I can make designs I tell them I can make anything, I just have to think about it and figure it out.

That's how I approach basket making and teaching and everything: There is always a solution.

Your residency spans the period when the North American Indigenous games are taking place here in Kjipuktuk (Halifax) but also in other spots in Mi’kmaki. What does that mean to you?

I was commissioned by the committee to provide baskets as gifts; I'm in the process of trying to complete them.

I believe it's going to be over a hundred thousand people during the summer that would be visiting Halifax. It'll be the ideal time to provide awareness of the Mi’kmaq and who we are and what we stand for in terms of conservation, rather than just monetary gain. It's a food source for us. And, tying in with the 1752 treaty, we're granted the right to hunt, trade and fish as a source of income as well.

The theme of the games, “Pjila’si” is usually translated into English as “Welcome”. What does it mean to you?

When I was growing up, when somebody come to visit, my grandma would always say, “Pjila'si”. Us kids, we had to get out of the room and make room for this person to come in and sit down. They were the pinnacle of the whole house at that time. That person's the most important person there. If you gave that person that greeting, “pjila’si”, it’s like “Hey, you're on the top pedestal.”

What does it mean about how guests are going to be treated?

They should be treated with utmost respect and hospitality, and whatever they need should be accommodated, to show how it feels to be welcomed by Mi’kmaq.Is there anything else that you want to say?

I'm really grateful and happy to be chosen to have this opportunity to show my work and share it. I'm going to be doing a lot of trial and error. I want to make sure the piece will be right.

Supported by TD Bank Group through the TD Ready Commitment Initiative.