How a vivid dream and a nearly forgotten history led to a new exhibition

Artist JJ Lee thought of herself as a second-generation Canadian, her parents having been born in China. A discovery in her childhood home set in motion a series of discoveries that revealed her family’s history in this country goes back a lot farther than she thought. It also inspired an artistic installation, on exhibit at the Museum May 12- July 23, 2023.

“Years and years and years ago I had a dream -it was very vivid- that I went up to the attic, and I found these drawings on brown paper that was a little bit stripey. Apparently, I had done them. And I’m like ‘I don’t remember doing these. That’s weird!’”

A homecoming to help move house

In 2020, with life disrupted by the pandemic, Lee (who lives in Toronto) was back in Halifax where she’d grown up. Her aging parents were moving to a retirement residence, and for two months she lived in the house she’d grown up in, faced with the daunting task of going through the house and deciding what to keep and what to throw away. She was able to teach her courses at the Ontario College of Art and Design remotely. Her husband, a kindergarten teacher, was teaching online too; their child was learning remotely.

Discoveries in the attic

A house accumulates a lot of things in a lifetime, as Lee discovered. She became very interested in the many papers- and the things made from paper-in the house. Paper is a Chinese invention with a deep history. But paper is also a conveyer. It can carry instructions, records, monetary value, laws, and memories. She found engineering diagrams her father had drawn as a student. Old receipts from her grandfather’s laundry in Halifax’s south end. A 1921 Chinese-English Dictionary.

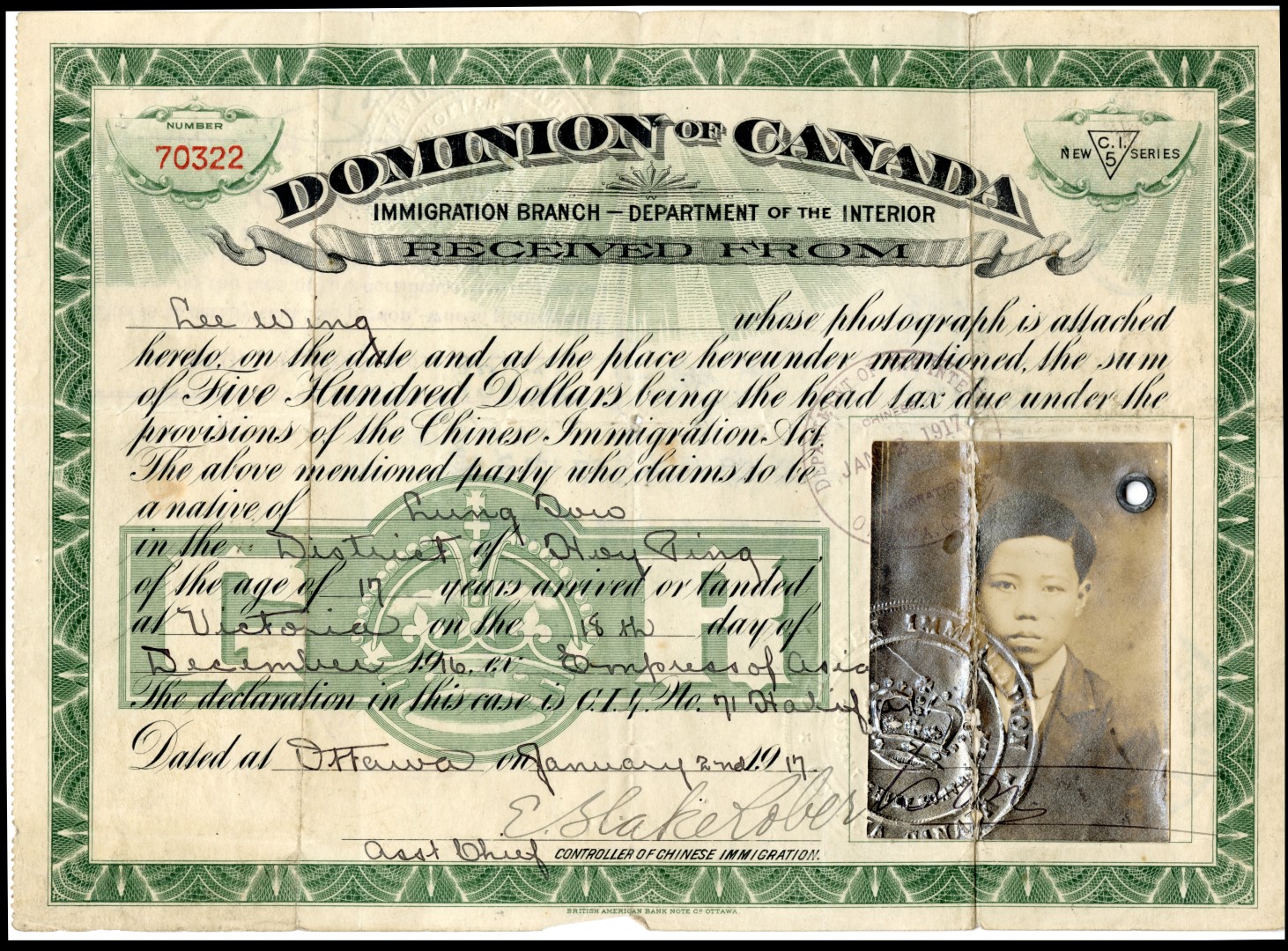

Perhaps most significantly she found a 1916 certificate issued by the Immigration Branch of the Dominion of Canada. It featured the picture of a 17-year-old boy.

“I was like ‘Dad who’s this?’ And he said, ‘That’s my father’.”

Beginning in 1885, the Canadian government began charging a duty to each Chinese immigrant arriving in Canada: the Head Tax. Starting at $50, the tax was increased to $500 by 1903. The restrictions escalated again after the First World War when the Chinese Immigration Act, 1923 almost completely prohibited Chinese immigration. From 1923 until 1947, when the racist exclusionary policy was repealed, only a handful of Chinese immigrants were able to enter Canada.

“Growing up I didn’t even know about the Head Tax,” she says.

She has asked her father why he never told the family about its history. His reply: “I didn’t think anyone would be interested.”

The various discoveries inspired an exhibition called In My Yesterday. It includes drawings, artifacts, digital collage, and animated video. Both the artwork and the exhibition are designed to feel “as if you’re walking through someone’s memory.”

Memory- its preservation and its loss- is meaningful to Lee. Last year, her mother died; her father’s memories were becoming harder to access because of his progressing Alzheimer’s disease. The process of creating artwork for the exhibition is a blending of her own memories and her family’s history. It is a way of remembering, reclaiming and reconstituting. She describes it as “a way of understanding this ancestral intergenerational story through the making of these drawings.”

A lot of the drawing that Lee has done is on paper she found while clearing out her parents’ home. She has drawn on old technical drawings her father made as an engineering student, layering her father’s decades-old lines with her own. A charcoal drawing, done on a notepad of lined paper found at the house, resurfaced the imprint of Chinese characters written by her mother. Though the imprints are still there, it’s impossible to make out their sense. Like an old jumbled childhood memory, the mark is undeniably there, but also lost to time.

“It’s hard to read because there were several letters written on that pad of paper. And I didn’t even realize it until I started drawing and the charcoal picked up the text. It might have been [from] the 90s or in the 50s, I have no idea.”

Lee knows that memories are not static. When you remember something, it’s like taking a sculpture made of Play-Doh down off the shelf for a bit and putting it back. Every interaction changes it a bit as the present mixes with the past.

Artistic inspiration or prophetic dreams

Among the paper she found in the attic was the brown, striped paper used to wrap folded laundry at her grandfather’s laundromat. It was the same paper she had seen in her dream years before.

Lee finds it slightly haunting that she is now living out her dream of years before. “It’s very weird,” she says.

“I was like, ‘Dad it’s kind of like my ancestor, grandpa or my great grandfather saying draw this and tell this story and do this show.’ Because it really doesn’t feel like my work.”

Adding herself to her family’s history

Museums preserve artifacts in an effort to capture history. Indeed, Lee donated a number of family belongings to the Museum’s collection. She is using other items, including brown striped paper from her grandfather’s laundromat, her father’s old technical drawings and old receipts, in the artwork for the exhibition. In drawing on the found paper, Lee imprints her own memories- and her own history-on her family’s.

She reflects, “It’s this kind of tension with using all of this historic paper, this vintage paper that has been living in an attic for decades. Or this other paper that’s been living in my parents’ drawers. But it also feels responsible.”

As Lee integrates her own memories with her newly discovered family history, it is both constructive and difficult.

“Since the time I found the objects and moved my parents out, my mom died. Now my father is in palliative care. Working on this show is very painful. Ever since my mom passed away-they were together 65 years-he hasn’t been the same. My dad is going to pass away any day now, so it feels even more important for me to tell this story and to honour them.”

Among the artifacts Lee has donated to the Museum’s collection are the head tax certificate, the dictionary, an application from her grandfather to bring his family to Canada, banking receipts, a Chinese encyclopedia, tax bills, and Certificates of Canadian Citizenship. Many of these artifacts, will be incorporated into Lee’s exhibition.

For Lee, it’s meaningful that her exhibition is in the same institution that houses artifacts from her family. “I love that it’s in the Museum,” she says.