First movement, Santiago de Cuba

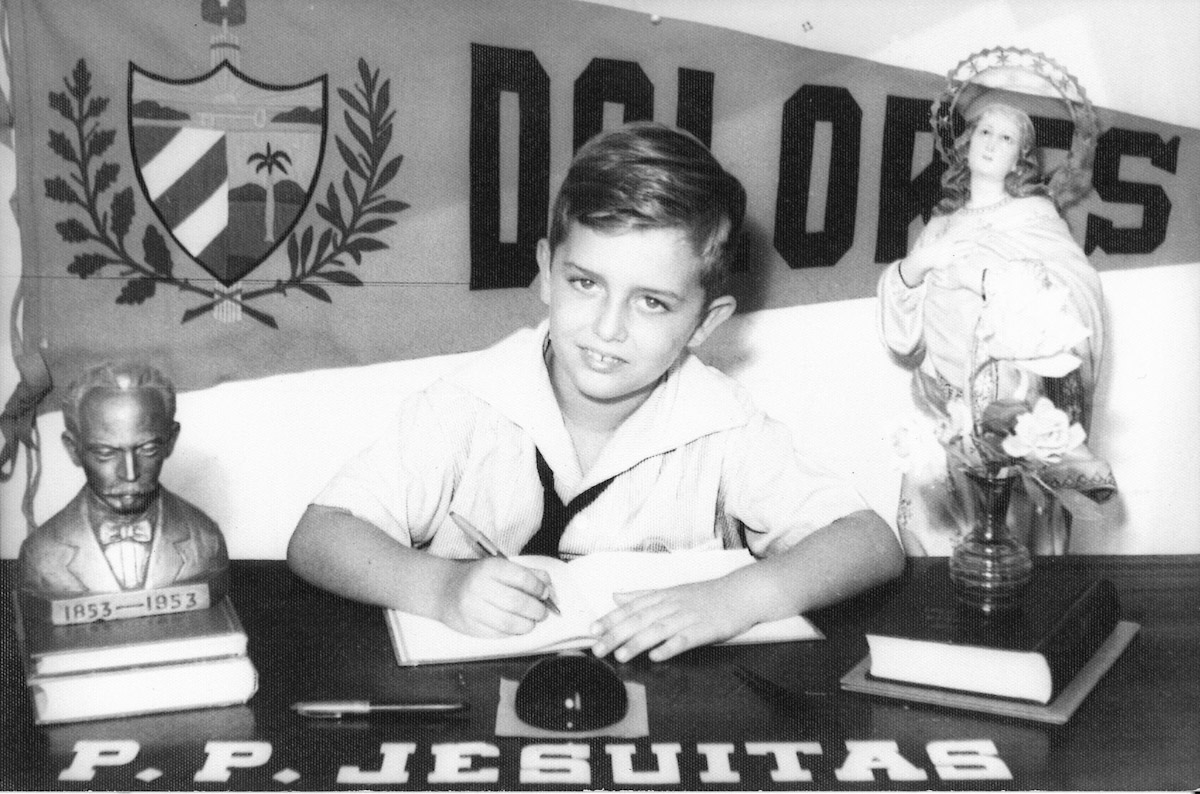

On January 1, 1959, Rafael Alcolado was a 12-year-old student at a Jesuit-run school, Colegio de Dolores, in Santiago de Cuba.

That same day, on the other side of the island, former student of Dolores Fidel Castro led a group of revolutionaries as they overthrew Cuba’s government and seized power.

In the next few years, Rafael’s world changed radically. As Fidel’s government veered towards communism, many professionals fled. Some estimate that 50% of Cuba’s doctors and teachers left the island. The Jesuits and other religious orders were expelled. Rafael was moved to a public high school. In the new Cuba, where loyalty to revolutionary ideals was mandatory, students like Rafael had to earn “revolutionary merits” by contributing unpaid labour harvesting sugar cane to prop up Cuba’s ailing economy.

Rafael wasn’t a good revolutionary. He felt those in authority weren’t telling the truth, but he couldn’t speak up. “I remember some of my friends saying to me, don't keep talking like that. You're going to be put in jail.”

Soon, he felt like he couldn’t trust anyone. He had no friends.

Rafael was a gifted musician - one of the youngest students to graduate from the Conservatorio Esteban Salas in Santiago de Cuba. In 1966, aged 19, he played in a music competition in Havana. “I was lucky that there were 2 famous pianists and pedagogues there by the name of Halina Czerny-Stefańska and her husband, Ludwik Stefański from Krakow, Poland.”

They invited Rafael to come to study music and live with them and arranged a scholarship. But it wasn’t easy for Rafael to leave the country because, “I didn't have enough revolutionary merits.”

Eventually, he was allowed to go.

Before leaving, he spoke with his family. “I told my parents, if I have a chance to stay anywhere in the world, they won't see me back here.”

Second movement, Krakow, Poland

Rafael studied at the State Music Academy in Krakow and later, at the Franz-Liszt College of Music in Weimar (then East Germany). But even abroad, he felt pressure from his home government. “I had to go once or twice a week to meet with other [Cuban] students,” he says. In order to earn revolutionary merits, “we were supposed to discuss for hours… about all the revolutionary, amazing things that were happening in Cuba... Everybody knew that they were all lies.”

Then, in December of 1970, he made plans to return to Cuba. His intention was never to go home. He’d heard the plane would have to refuel at an airport en route where he might have the opportunity to claim asylum.

Third movement, Gander, Newfoundland

There were several other Cuban students on the flight, including one assigned to sit next to Rafael and prevent him from defecting. “This person had more revolutionary merits than I had. He had my passport.”

When the plane touched down in Gander to refuel, the immigration officer took everyone’s passports to hold during their short stop in the terminal.

It was around 2 am, December 24. In the airport, they ate. They waited. Rafael’s mind worked, trying to make a plan. He noticed that adjacent to the Immigration office was an area with an art exhibition.

He suggested to his companion that they go and have a look at the paintings. “I had a suspicion he didn't have any affinity for the arts, so I stayed in front of each picture for a long time until, after the 3rd or 4th picture, he got tired of standing with me. And I said… ‘Just go and sit over there.’”

Then, he says, “I took my comb, gave it to him and said ‘your hair looks terrible.’ He went to the bathroom, which was exactly in the opposite direction... As soon as I saw his back disappear into the bathroom, I ran into the immigration office.”

There was just one person working in the office, head down, asleep. Rafael pounded on the desk. The officer woke up, disoriented.

“I said, ‘Please, I am a Cuban student. I want to ask for political asylum.’ I had to repeat it many times because I was so nervous. And then I proceeded to ask him, please lock me up in that room over there.”

The officer reassured him he was safe.

“I said, no. You have to lock me up in that room. He saw the fear in my eyes, and he locked me up in that room.”

He had only his backpack with 4 or 5 changes of underwear, perhaps a bit of toothpaste and some music books. Everything else was on the plane.

Through a window inside the locked room, he eventually saw the plane take off.

“I didn't have a Canadian penny in my pocket, but that was one of the happiest days in my life because I figured I'm at the bottom of everything. From here, I can only go up. And I am free.”

Fourth movement, Halifax, Nova Scotia

Later that day, Rafael was flown on a large Air Canada plane from Gander to Halifax to be processed at Pier 21’s immigration facilities. It being Christmas Eve, there were only about 12 people on the flight.

“I remember there was a big storm because the bus took 2 and a half hours from the airport to Pier 21. Normally, you can make that trip in half an hour.”

The bus made stops to let other passengers off. By the time it arrived at its final destination, about a block from Pier 21, Rafael was the only passenger remaining.

As he disembarked from the bus, he was greeted by a man in his 60s. He said he’d been sent to receive Rafael. He spoke in Spanish in an accent that was recognizably Cuban.

Rafael was on edge immediately.

“I said to him, “Look. You're Cuban. I am Cuban. You know I must fear you right now. I don't know if you have connections with the [Cuban] embassy. So I'm not going to walk next to you. You have to walk ahead of me to convince me that you are taking me to an immigration office.”

The man replied that he’d arrived a few days prior and understood perfectly. They agreed that Rafael would follow about a block behind.

The walk to Pier 21 was via a long pedestrian overpass. Rafael kept his distance until the man disappeared inside a door. When Rafael reached the door, he too went through it.

Inside Pier 21, Rafael was greeted by a guard. He seemed to be the only person working there. No immigration officers were on duty to receive him because of the holiday. They would be in the following week, the guard explained.

As he looks at Pier 21 today, Rafael recognizes the windows from the room where he stayed for several weeks with other asylum seekers from communist countries. He recalls there were Polish, Bulgarians, East Germans and more, all seeking a new life of freedom.

Fifth movement, home

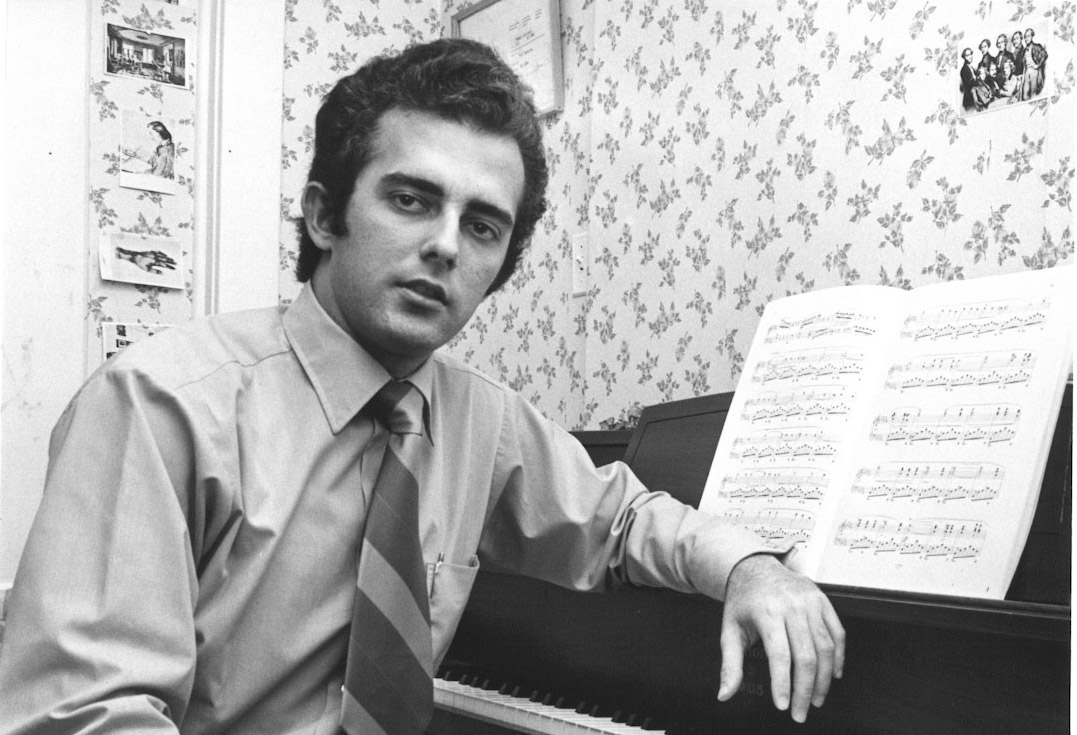

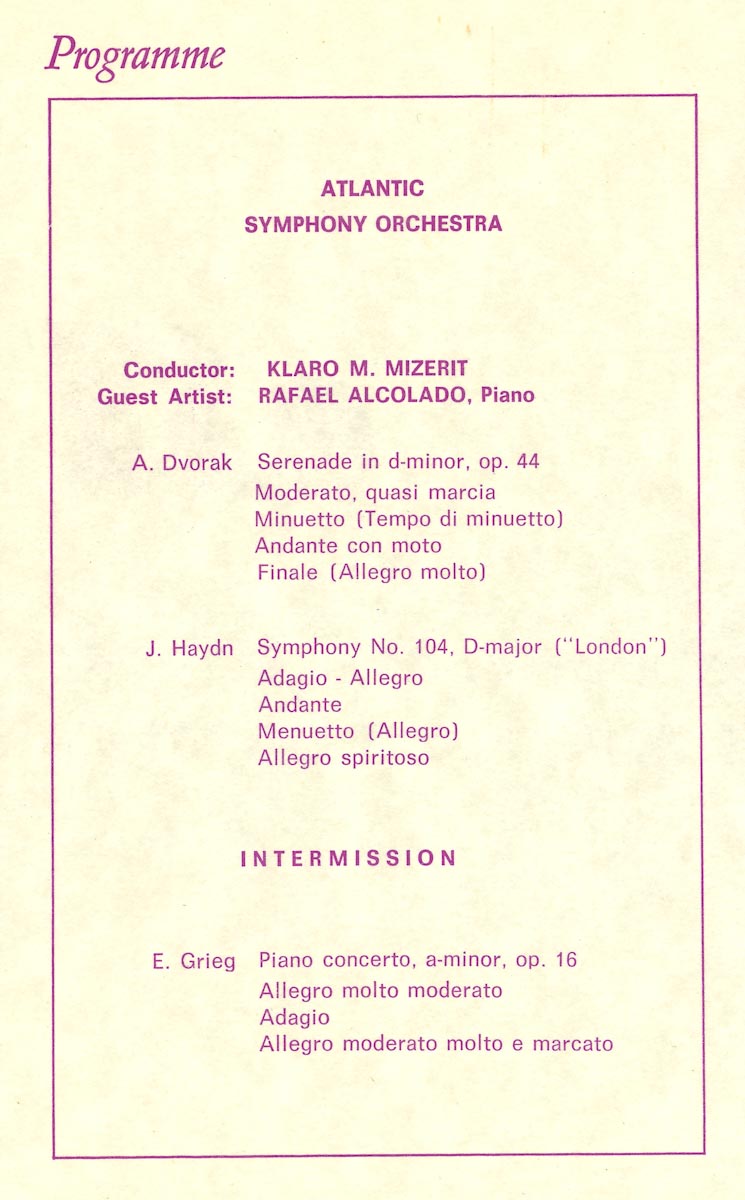

Bit by bit, Rafael began to build a life in Halifax. He found a place to live. He made friendships within the local Polish and Cuban communities. He was introduced to a local accountant who owned a baby grand piano Rafael could practice on during the day. A university professor and his wife, a former concert pianist, helped attract students for him to teach. A little over a year after his arrival, he made his North American debut, performing with the Atlantic Symphony Orchestra.

Last year he celebrated his 50th wedding anniversary to Elizabeth Susanne Alcolado, a Newfoundlander he met in Halifax. They have three children and three grandchildren.

Although officially retired, music is still central to Rafael’s life.

“This is the 3rd stage of my life as a musician in Canada. The first stage was playing with the Atlantic Symphony Orchestra and doing concert work... The second stage was teaching most of the time,” and now, his principal musical activities are arranging music for Sunday worship at Hope United Church in Halifax, where he has been the organist for over 40 years.

His arrangements include parts for instruments played by the minister, her husband, and members of the congregation: acoustic bass, saxophone, two flutes, a trumpet, drums, and a bagpipe.

“I'm having fun with my retirement.”