by Lindsay Van Dyk, Former Junior Researcher

(Updated November 19, 2020)

Introduction: The Arrival of Black Refugees Related to the War of 1812

Nova Scotia has been home to people of African descent for over 300 years. Some individuals came as slaves in the service of white masters, but many others arrived as free migrants seeking a new homeland. During and following the War of 1812, approximately 2,000 escaped slaves arrived in Nova Scotia, having attained freedom in the course of the conflict. An estimated 400 of this number journeyed onward to New Brunswick. This group collectively became known as the Black Refugees.

Nova Scotia has been home to people of African descent for over 300 years.

Upon their arrival in Nova Scotia, the Black Refugees experienced many hardships. The government withheld land grants, an influx of white immigration increased competition for the few jobs available, and the rocky, infertile land proved difficult to cultivate. Under these conditions, extreme poverty became a reality for many Black Refugees. White society had difficulty accepting the new immigrants as free settlers since black individuals were often perceived of as slaves. As a result, the Black Refugees were largely excluded from Nova Scotia society. Despite their marginalization and impoverishment, the Black Refugees made valuable contributions to Nova Scotia’s cultural fabric as they established enduring communities throughout the province and helped to shape the development of an African Nova Scotian identity.

Previous Black Migrations to Nova Scotia: The Black Loyalists and Jamaican Maroons

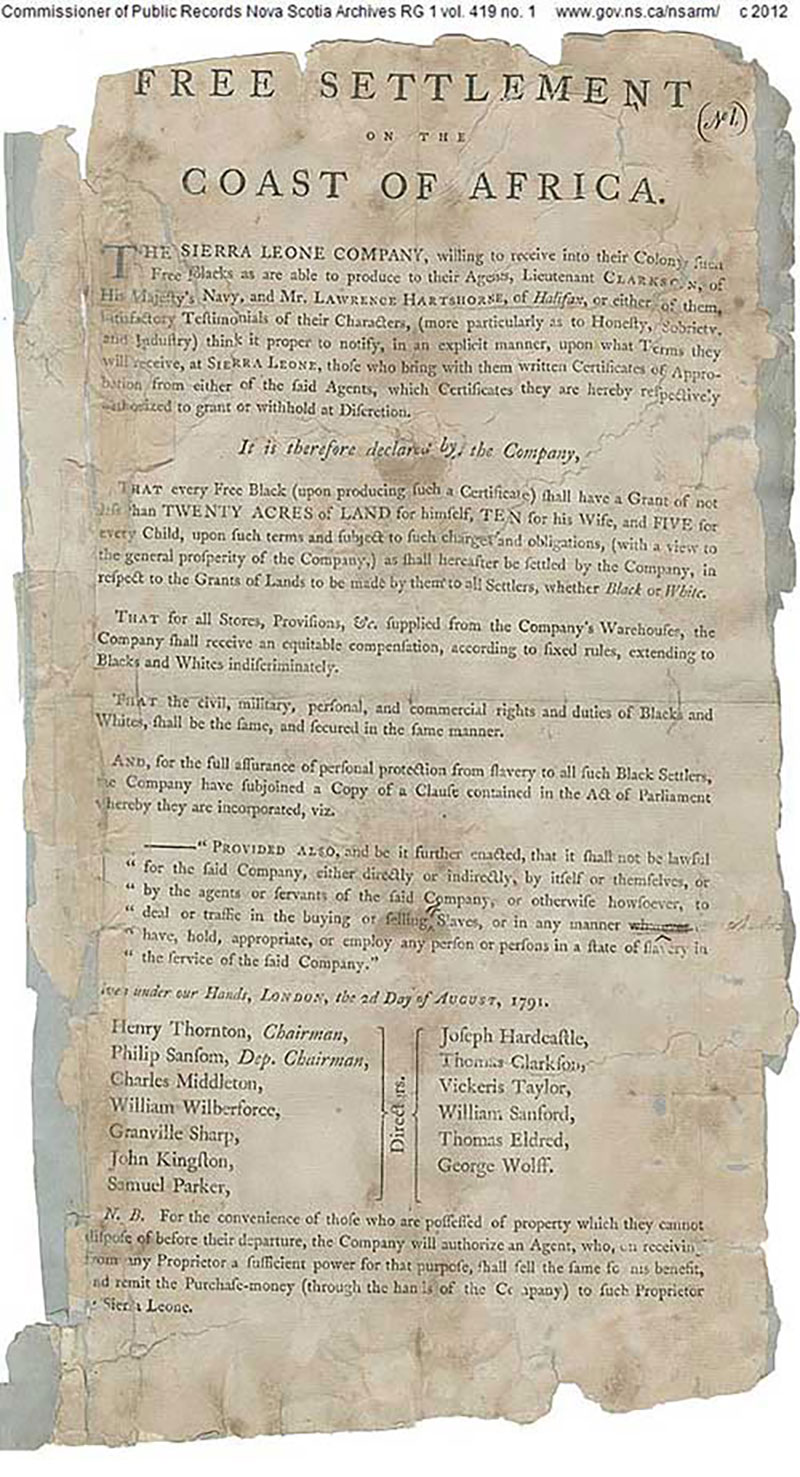

The Black Refugees are considered the third major wave of free black migrants in Nova Scotia, preceded by the Black Loyalists (1783) and the Jamaican Maroons (1796). Over one third of the Black Loyalists and nearly all of the Jamaican Maroons eventually resettled in Sierra Leone.

The experience of the Black Refugees in Nova Scotia was heavily influenced by previous Black migrations into the province. Until the late eighteenth century, the majority of the province’s Black population consisted of enslaved individuals. In the early 1700s, approximately 300 slaves were brought to the French stronghold at Île Royale in present day Cape Breton, while additional numbers of slaves arrived between 1760 and 1774 in the service of New England settlers. The presence of black slaves prior to the arrival of any free migrants conditioned many white Nova Scotians to equate black skin colour with slavery, negatively influencing their attitude toward later black immigrants.[1]

The first large-scale migration of free Blacks into Nova Scotia occurred in the aftermath of the American Revolutionary War. During the conflict, the British offered liberty and protection to any black slaves that fled their American masters and took up arms with the British. More than 3,000 Black Loyalists came to Nova Scotia following the British defeat in 1783, settling in Birchtown, Digby, Guysborough County, Annapolis Royal, Preston, and Halifax. By 1785, most Black Loyalist communities had established independent black churches and many also had their own schools.[2] However, the Black Loyalists were consistently denied land grants and exploited as a source of free labour by the provincial government. Disillusioned with their experience in Nova Scotia, over one third of the Black Loyalists opted to resettle in Sierra Leone in 1792. Included in this number were the majority of the black teachers, preachers, and leaders, leading to the disruption of Black Loyalist communities and institutions.[3]

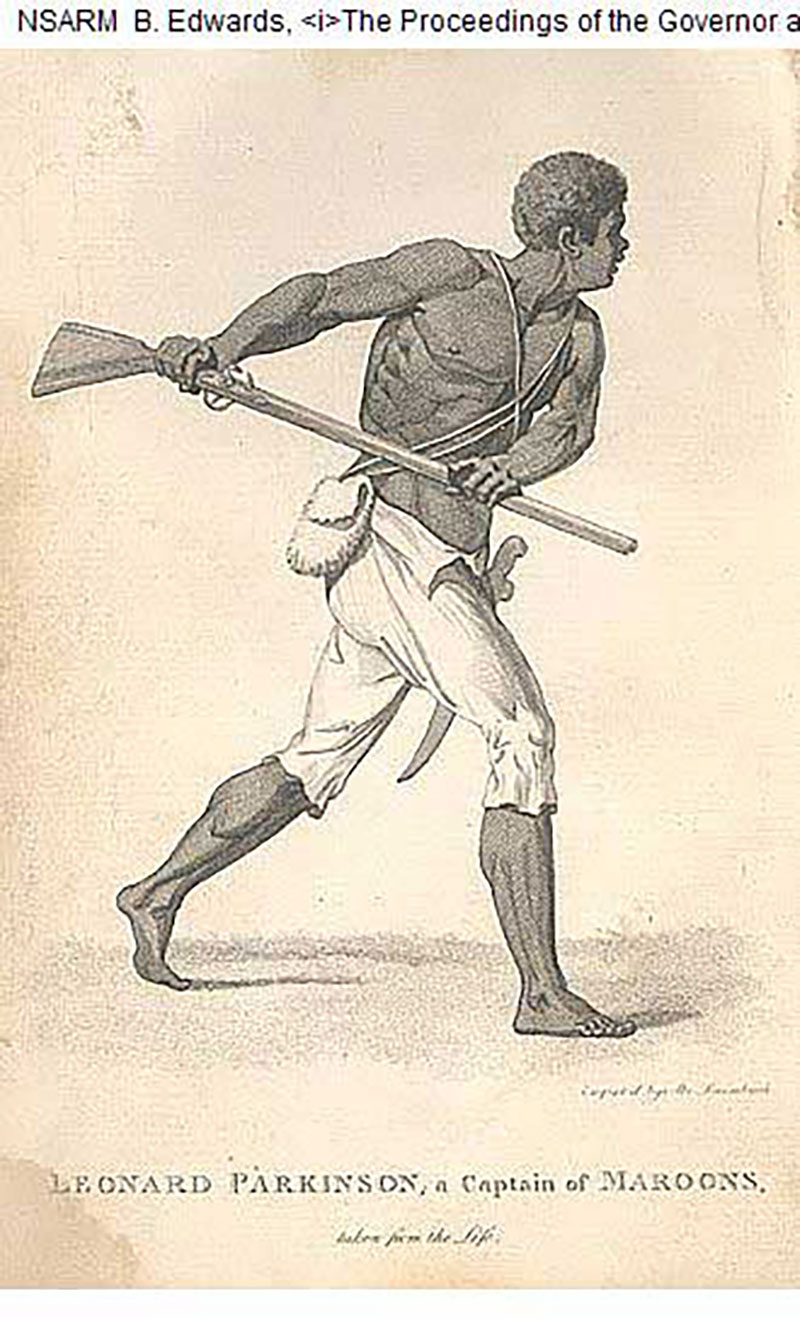

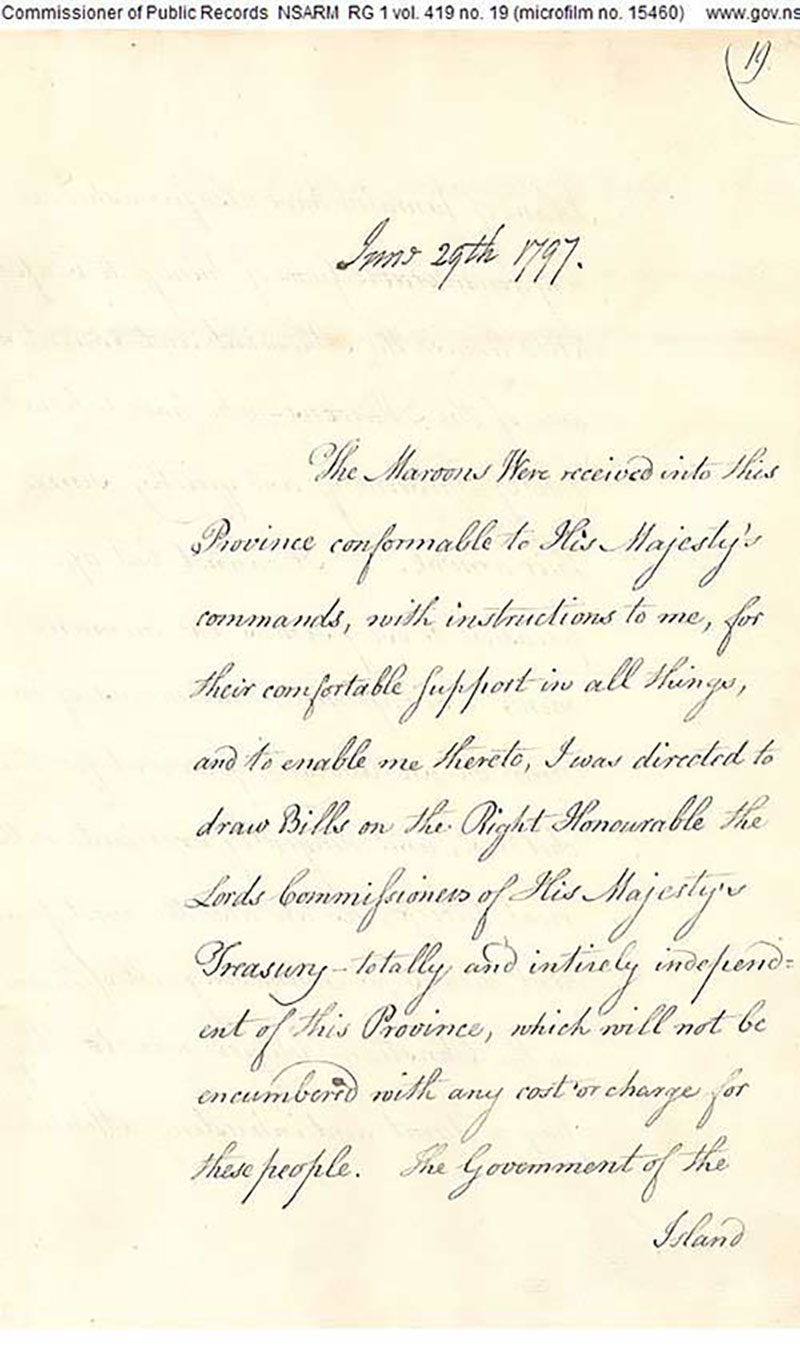

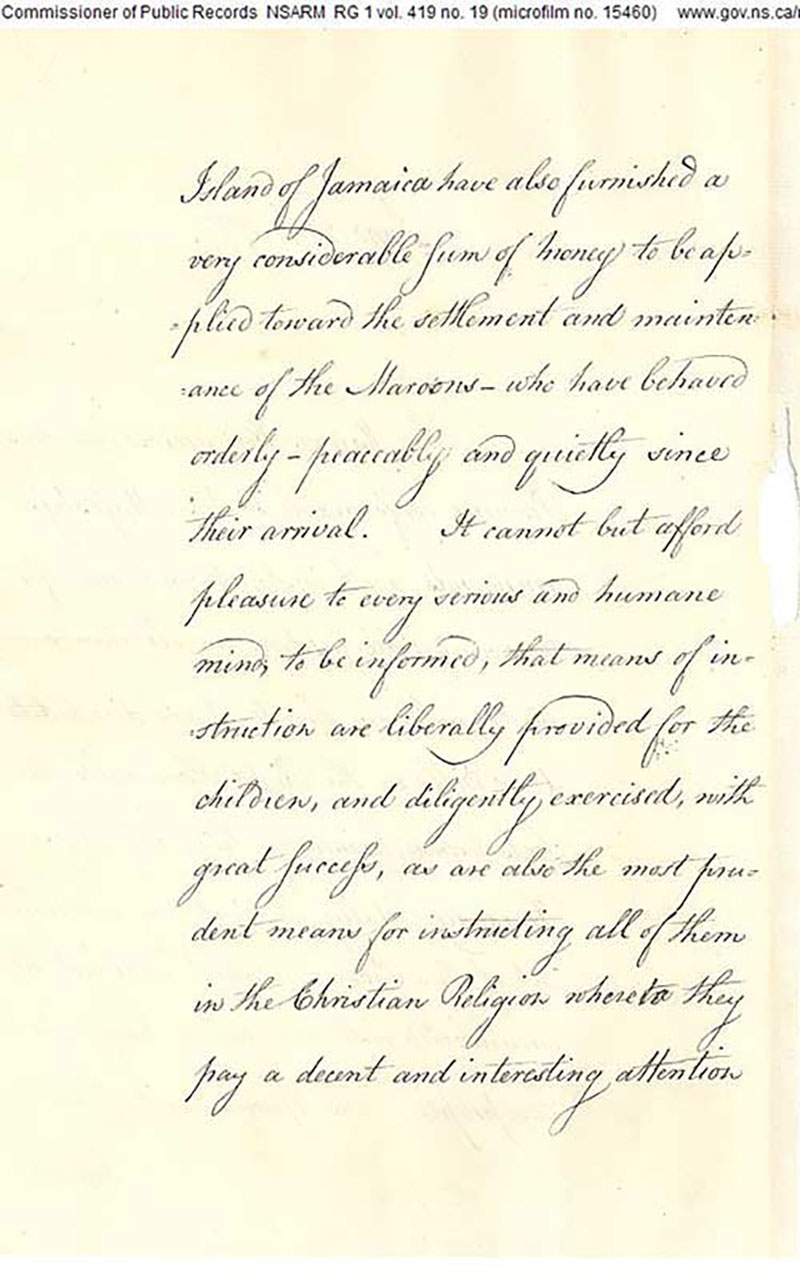

The arrival of over 500 black Maroons from Jamaica in 1796 signalled the second mass migration of free Blacks into Nova Scotia. British colonial authorities had expelled the Maroons from Jamaica after an uprising against the island’s colonial government. Many of the Maroons were employed by the British to work on the fortifications at Citadel Hill. However, the Maroons had difficulty adapting to the harsh climate of Nova Scotia and resented the government’s attempts to convert them to Christianity and use them as cheap labourers. Growing dissatisfaction with their experience in Nova Scotia influenced nearly all the Jamaican Maroons to voluntarily resettle in Sierra Leone in 1800.[4] By the time the Black Refugees migrated to Nova Scotia, the Black population remaining in the province was widely scattered and isolated.[5]

Black Refugees Settle in Nova Scotia, Experience Adverse First Years

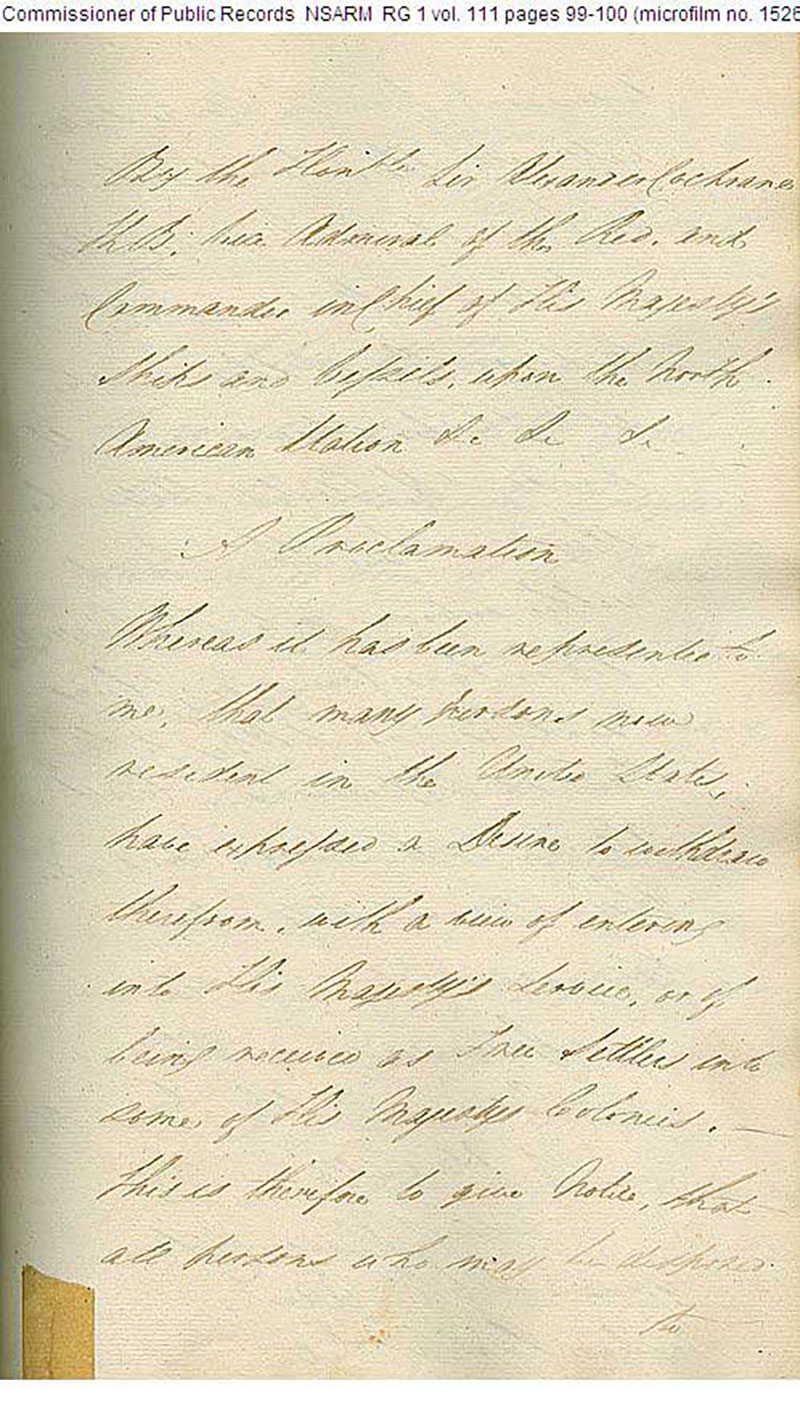

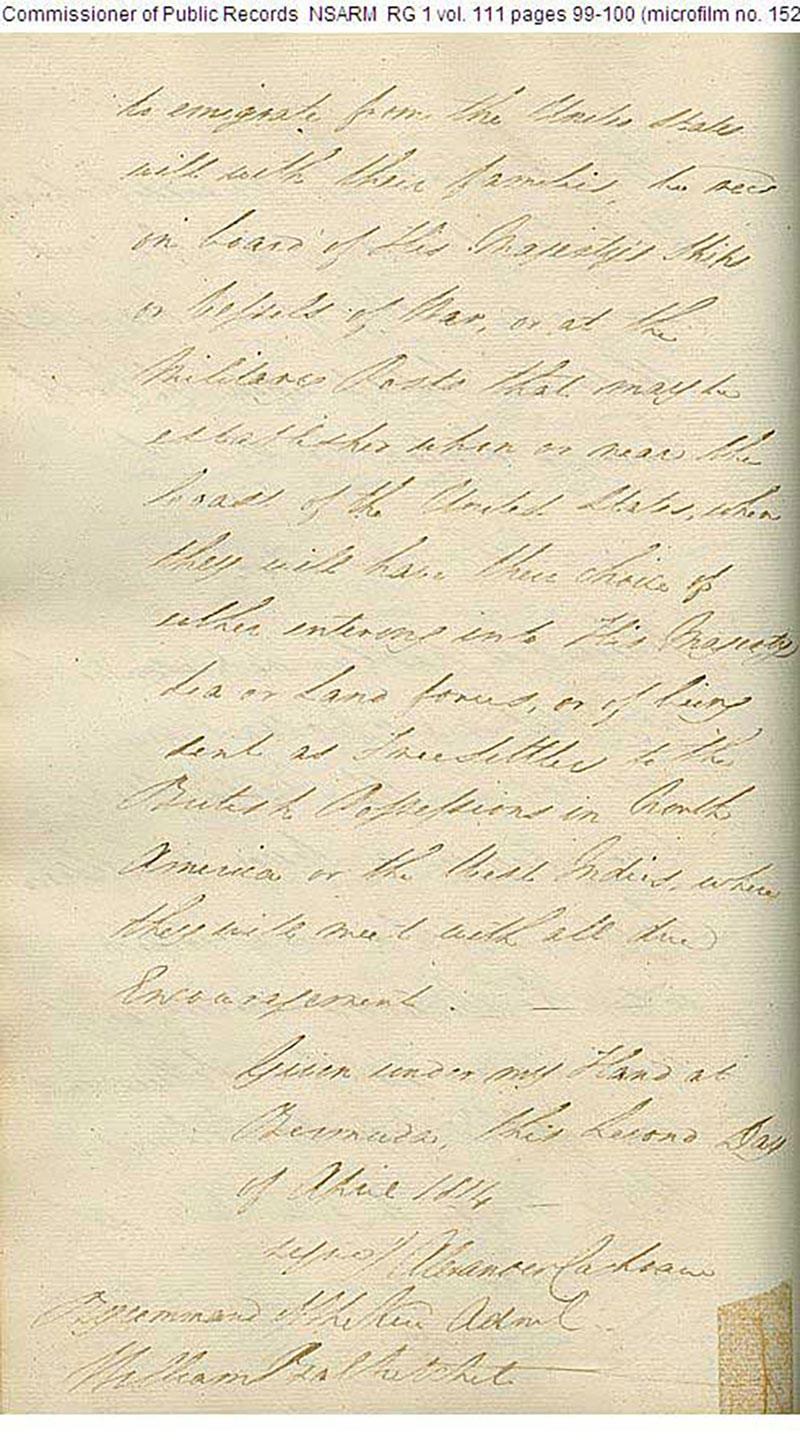

The advent of war between the United States and Britain in June 1812 provided the Black Refugees with the opportunity to escape their enslavement. Lingering feelings of dissent from the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) had gradually escalated into a full scale conflict.[6] When the British set up a naval blockade on the eastern coast of the United States in 1813, slaves began to escape their plantations and seek refuge aboard British ships. In April 1814, Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane issued an official proclamation offering freedom to anyone that joined the British side, promising resettlement in the British colonies in North America and the West Indies.[7] Between 1813 and 1815, approximately 3,500 slaves successfully escaped, primarily coming from the Chesapeake region (Maryland and Virginia) and coastal Georgia. Nearly 2,000 Black Refugees were transported to Nova Scotia, with 400 of this number conveyed to New Brunswick in 1815.[8]

Adversity and struggle characterized the first years of Black Refugee settlement in Nova Scotia. Many of the Black Refugees arrived sick and impoverished and were unable to work, forcing them to seek refuge in the Halifax Poor House or at the quarantine centre on Melville Island. Those in good health were sent into the interior of the province to search for employment. Lieutenant Governor Sir John Coape Sherbrooke expressed confidence in their ability “to maintain themselves comfortably by their Labour.”[9] However, the end of the war in 1814 initiated a period of economic depression within Nova Scotia, making it difficult for the Black Refugees to obtain wage labour. An increase in European immigration during the same period intensified competition for the few jobs available.[10] Many Black Refugees were reduced to begging and stealing in order to provide for themselves and their families.[11] In spite of these difficulties, the Black Refugees were intent on settling in Nova Scotia.

Difficult Farming Conditions and Lack of Acceptance From White Populations

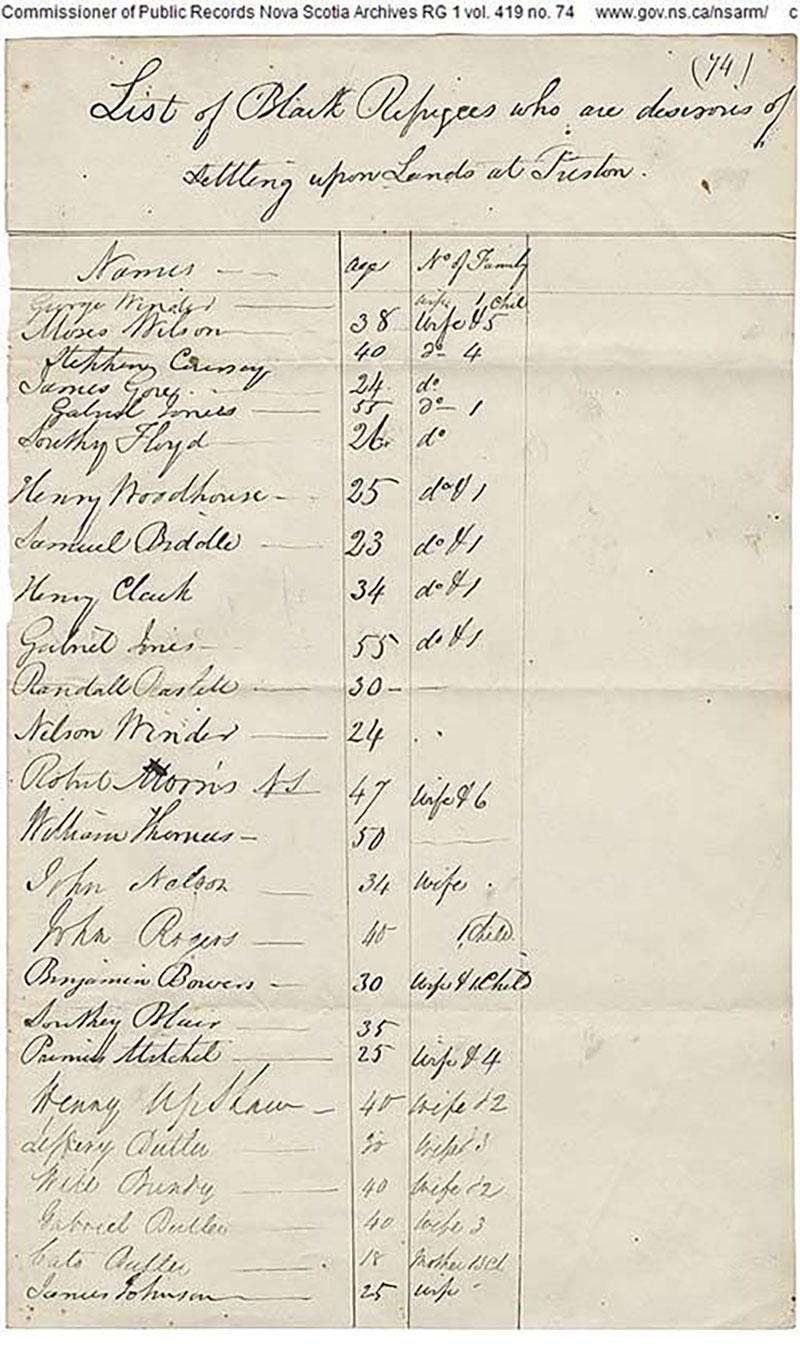

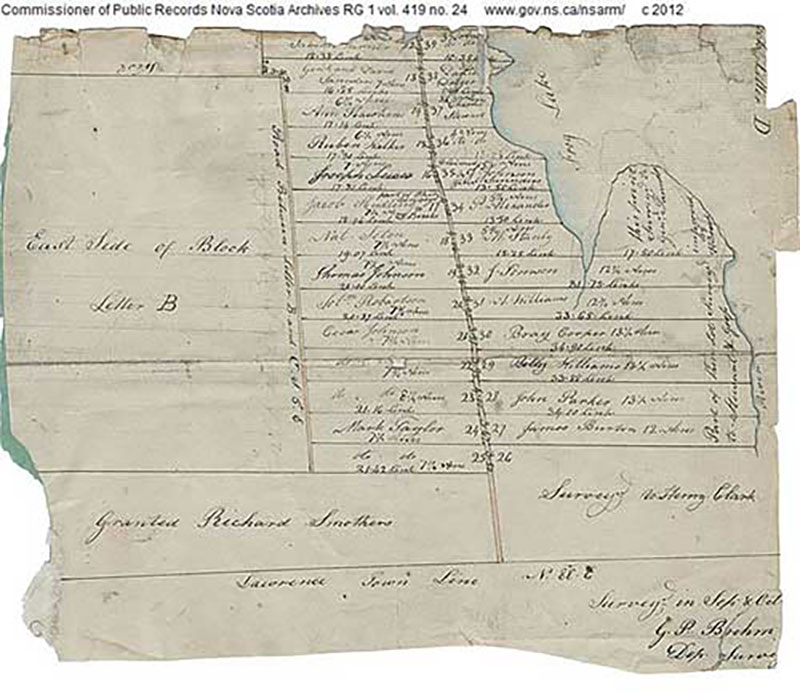

The Black Refugees settled in the rural areas around Halifax, with the largest communities established at Preston, Hammonds Plains and Beechville. Initially, the settlers were “well pleased and satisfied” at the prospect of having land to call their own.[12] However, the government did not give the Black Refugees outright grants to the land, but rather tickets of location or licenses of occupation. This denied the Black Refugees the opportunity to own land or sell it for a profit. The lots provided by the government were limited to ten acres and located on rocky, infertile soil. In these conditions, crops planted by the Black Refugees repeatedly failed. A series of devastating natural events made efforts to cultivate the land even more difficult. In 1815, entire fields were destroyed by hordes of mice that swept across Nova Scotia’s countryside. The following year became known as the “Year without a Summer,” as the ground stayed frozen until June and ten inches of snow fell that same month. Even when the Black Refugees did achieve some success in producing crops, the long, cold winter seasons generally depleted their resources. Many Black Refugees were forced to rely on government assistance and private charity despite their best efforts to become independent.[13]

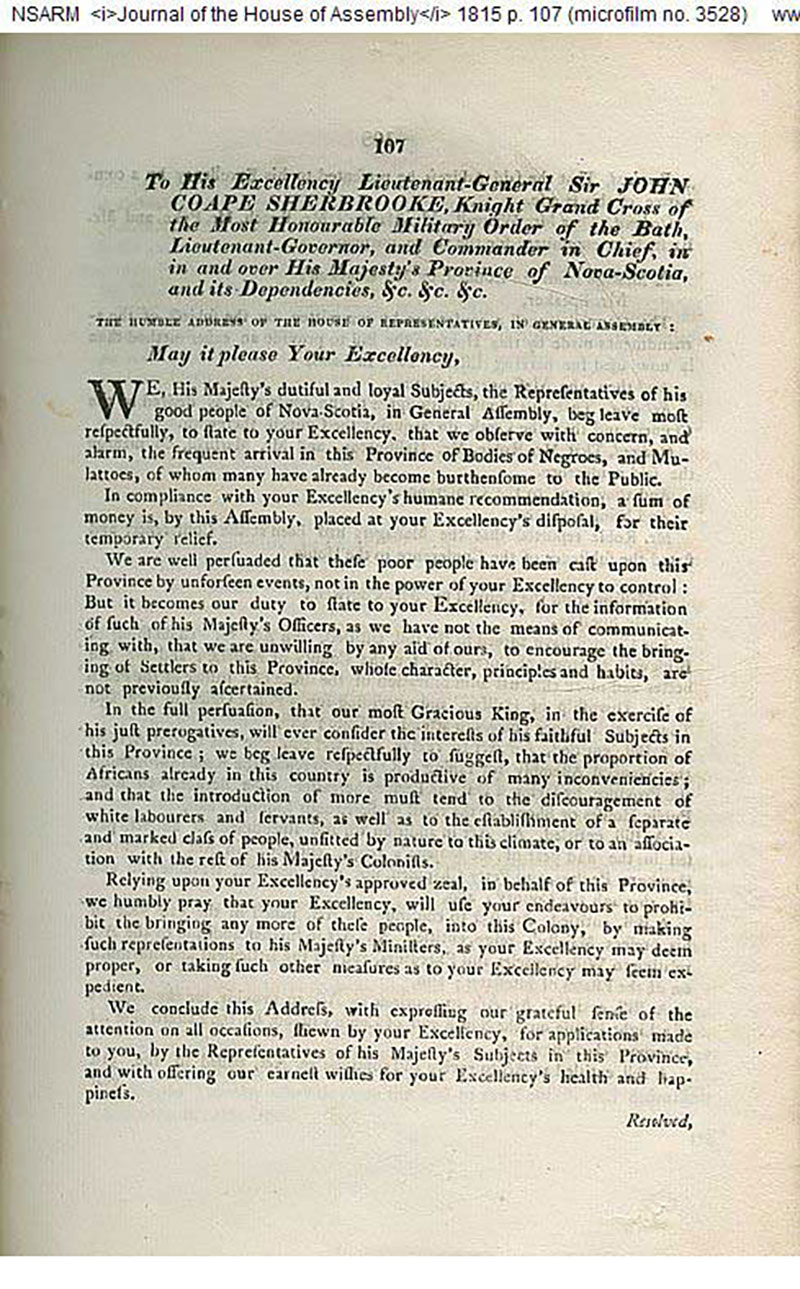

Provincial authorities protested that the Refugees were "unfitted by nature to this climate, or to an association with the rest of His Majesty's Colonists."

The white population of Nova Scotia resented the dependence of the Black Refugees versus other farmers amid these calamities and did not accept them as equal members of society. Provincial authorities protested that the Refugees were “unfitted by nature to this climate, or to an association with the rest of His Majesty’s Colonists.”[14] The general poverty of the Black Refugees was regarded as proof that the Black population was more suited to slavery than freedom.

Failed Resettlement by Colonial Authorities and a Commitment to Establishing Sustainable Communities

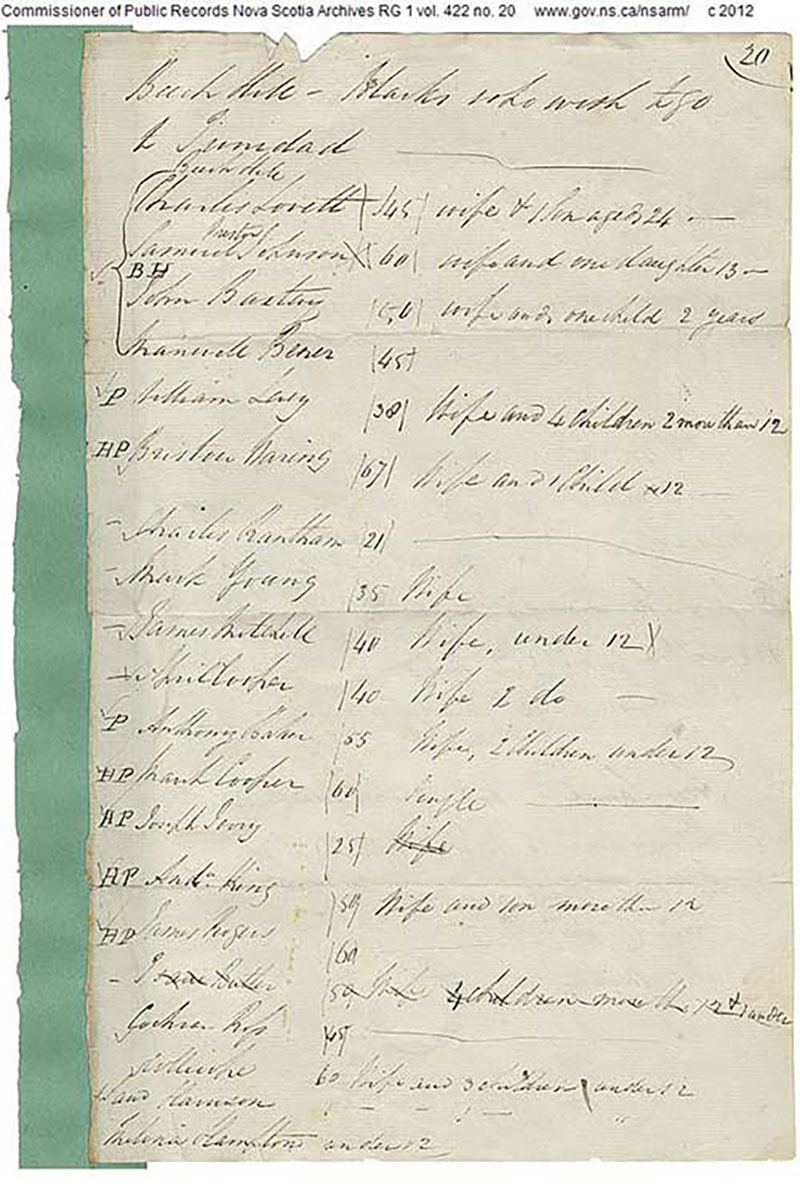

In 1821, colonial authorities attempted to remove the Black Refugees from Nova Scotia by pressuring them to resettle in Trinidad, but the majority refused to relocate to any place where slavery still existed.[15] In the end, only 81 adults and 14 children accepted the government’s offer for resettlement.[16] Despite their ongoing struggles, most of the Black Refugees were unwilling to leave their new communities and risk their freedom by relocating to Trinidad. The influx of Black Refugees into the province had facilitated a community revival amongst the Black population. Many of the Black Loyalists remaining in Nova Scotia migrated to the Black Refugee settlements and integrated into their communities.[17] The shared experiences of hardship created a sense of unity amongst the Black population and contributed to the growth and renewal of distinct black communities in Nova Scotia.

The Black Refugees did not passively accept the difficulties of settling in Nova Scotia.

The Black Refugees did not accept the difficulties of settling in Nova Scotia. Some of the Black Refugees sought employment in Halifax after continual crop failures. Men occasionally found work on ships or in the dockyards, while women primarily worked as domestic servants.[18] The sale of strawberries, raspberries and blueberries at the Halifax market provided an additional source of income.[19] Other Black Refugees petitioned the government for more land to improve their chances of harvesting a viable crop. Although these petitions were often ignored in the early years of settlement, the Black Refugees at Hammonds Plains received a grant for an additional 600 acres in 1834, while the Preston Refugees received 1,800 acres in 1842.[20] As the Black Refugees made efforts to improve their situation, they demonstrated a commitment to establishing sustainable communities.

The Importance of the Church for Black Refugees and Black Communities

The church offered the Black population a sense of security and strength in the midst of hardships. It was a place where the community could come together to worship, hold meetings and events and support one another.

The development of Black churches within Refugee settlements further strengthened the presence of the Black Refugees in Nova Scotia. Although independent Black churches previously existed in Black Loyalist communities, most disbanded in the wake of the Loyalist exodus to Sierra Leone.[21] Under the leadership of Richard Preston, the African Baptist Church was founded in Halifax in 1832, leading the way for the creation of other Black churches in surrounding areas. The church became the focal point of community life and provided the Black population with a sense of security and strength in the midst of hardship. Gradually, the Black Refugees founded other social and religious organizations, including the African Friendly Society, the African Abolition Society, and the African United Baptist Association. These institutions built up the Black Refugee communities and helped the Black population establish an enduring presence in the province as African Nova Scotians.[22]

The Black Refugees were not the first Black migrants in the province, nor were they the last, but their endeavour to persist in the face of white prejudice, infertile land, and poor economic prospects helped sustain the Black presence in Nova Scotia. The lasting impact of the early Black Refugee communities is still evident in contemporary Nova Scotia. Communities like Preston, Hammonds Plains and Beechville still have sizeable and active Black communities, while African Nova Scotians remain one of the largest visible minority groups within the province.[23]

Conclusion: Continued Growth And Cultural Contributions Over Time

Did You Know?

William Hall, the first Nova Scotian to receive the Victoria Cross, was a descendant of the Black Refugees. He received the medal for his actions at the Siege of Lucknow in 1857.

Over time, the Black community has continued to grow and make valuable cultural contributions. In 1983, the Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia officially opened as an institution dedicated to the protection, preservation and promotion of Black culture in Nova Scotia. More recently in 2000, the Nova Scotia Department of Education introduced high school Social Studies and English courses focused on African Canadian heritage and history. African Nova Scotians remain a definitive part of Nova Scotia society, building upon the cultural foundations of previous generations. Despite their struggles with poverty, destitution and discrimination, the Black Refugees created lasting settlements and strengthened the foundation of an African Nova Scotian identity.

Timeline:

1783-1785 –Approximately 3,000 Black Loyalists arrive in Nova Scotia. During the American Revolutionary War, the British offered freedom to Black slaves that joined the British war effort. When the British lost the war, those loyal to the Crown were forced to flee the United States. Black Loyalists came to Nova Scotia and settled at Birchtown, Digby, Guysborough County, Annapolis Royal, Preston, and Halifax.

1792 – Approximately 1,200 Black Loyalists leave Halifax for Sierra Leone. Denied land grants and exploited as a source of free labour, many Black Loyalists became dissatisfied with their experience in Nova Scotia. Over one third of the Black Loyalists chose to resettle in Sierra Leone, including the majority of Black teachers, preachers, and leaders.

1796 – Over 500 Jamaican Maroons arrive in Nova Scotia. The British colonial authorities expelled the Maroons from Jamaica for inciting a rebellion against the colonial government. The Maroons settled near Preston and were employed to work on fortifications at Citadel Hill.

1800 – Nearly all the Jamaican Maroons leave Halifax for Sierra Leone. The Maroons had difficulty adapting to the harsh climate and resented the government’s attempts to convert them to Christianity and use them as cheap labourers.

1812 – United States declares war on Great Britain. Lingering feelings of dissent from the Revolutionary War (1775-1783) had gradually escalated, intensified by American expansionism and the British Royal Navy's search and seizure of American vessels.

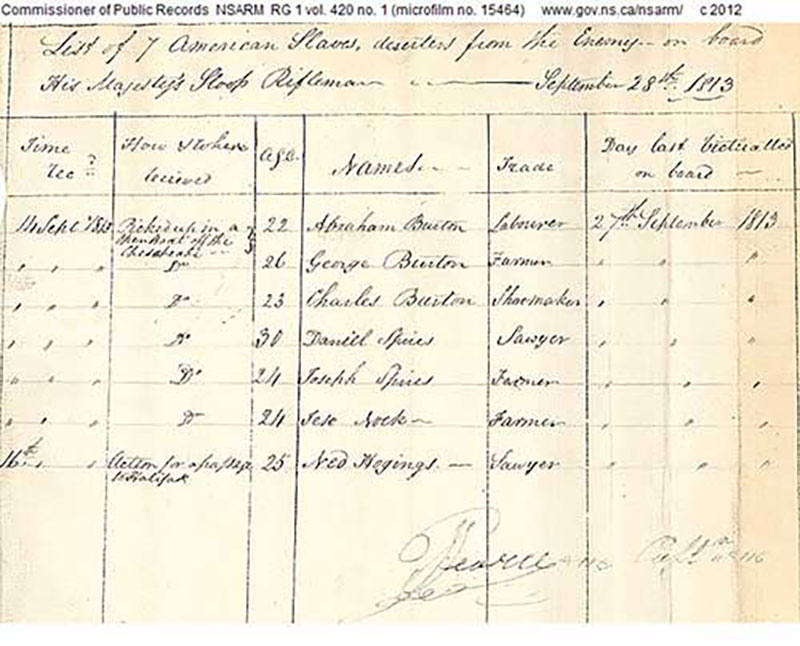

1813 – Black slaves seek refuge aboard British vessels. In the spring of 1813, the British set up a naval blockade in the Chesapeake region on the eastern coast of the United States. The proximity of British ships to the mainland prompted slaves to escape their plantations. In September of that year, 133 Black slaves were brought to Halifax.

1814 - Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochran issues a proclamation of freedom. In response to the continued escape of slaves to British vessels, Cochran officially offered freedom to Black slaves wishing to join the British side. The proclamation stated that individuals would be resettled in the British colonies in North America and the West Indies.

1815 – Between 1813 and 1815, approximately 2,000 escaped slaves arrive in Nova Scotia via British ships. This group of migrants became known as the Black Refugees and primarily originated from the Chesapeake region (Maryland and Virginia) and coastal Georgia.

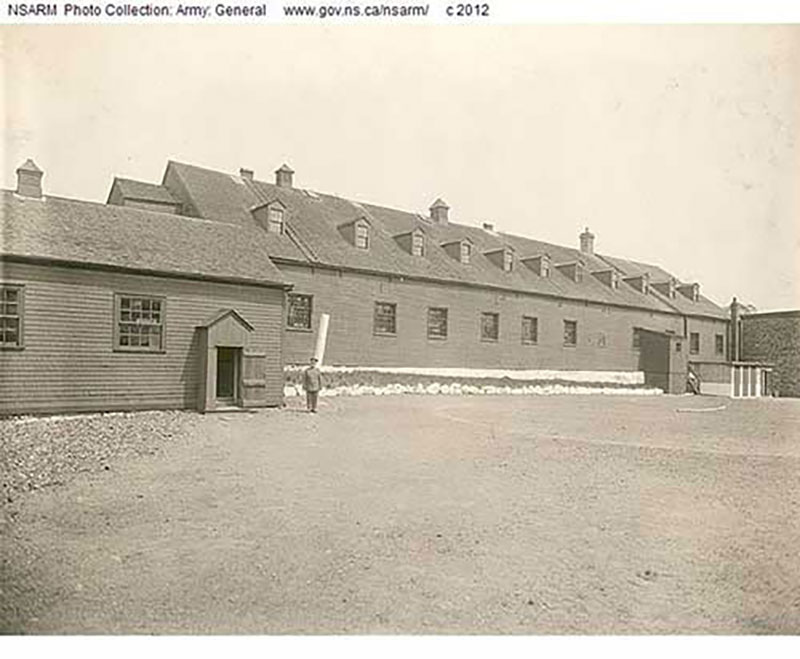

1815 – Melville Island opens as a quarantine centre for new Black migrants. In its first months of operation, Melville Island received over 700 Black Refugees. The centre was shut down in 1816 after a significant decrease in Black migration. Today it is the site of the Armdale Yacht Club.

1815-1816 – Refugees settle on land in the rural areas near Halifax. The largest settlements were formed at Preston, Hammonds Plains, and Beechville. The government withheld land grants from the Black Refugees and the rocky, infertile land proved difficult to cultivate.

1816 – Richard Preston arrives in Nova Scotia. Preston was a former slave that came to Nova Scotia in search of his mother. Intending to pursue a career in ministry, Preston became an apprentice of Reverend John Burton and gained popularity amongst the Black Refugee population as he traveled to the settlements delivering sermons.

1821 – Ninety-five Black Refugees relocate to Trinidad. The government had plans to resettle the Black Refugees in Trinidad as early as 1815, but did not have the resources to pursue the plan until the colonial government offered to subsidize relocation. Despite consistent government pressure, the majority of the Black Refugees refused to resettle in Trinidad.

1832 – Richard Preston receives his ordination in England from the West London Baptist Association. While overseas, Preston also raised funds for the erection of an independent Black church in Halifax.

1832 – Richard Preston founds the African Baptist Church in Halifax. It was later incorporated as Cornwallis Street Baptist Church in 1892. Between 1832 and 1853, Preston would establish a total of eleven African Baptist churches in Nova Scotia.

1833 – Slavery is officially abolished in the British Empire. The law would go into effect the following year.

1834 – Nova Scotia House of Assembly passes a law barring liberated slaves from arriving in the province. The Imperial government later disallows this law on discriminatory grounds.

1846 – The African Methodist Episcopal Zion Chapel is founded. For over a century, the church stood at the southwest corner of Gottingen and Falkland Streets. It was demolished ca. 1955.

1848 – Black Refugees settle at Africville. William Brown Sr. and William Arnold purchased land on the southern shore of the Bedford Basin in Halifax. People from the Black Refugee communities at Hammonds Plains and Preston began settling there and the area gradually became known as Africville.

1854 – Richard Preston and Septimus Clarke found the African United Baptist Association. The AUBA united Black churches across Nova Scotia and provided them with organizational structure.

Image Gallery:

Images from the Nova Scotia Archives

- Declaration of Sierra Leone Company

https://archives.novascotia.ca/Diaspora/archives/?ID=1 - Maroon Captain

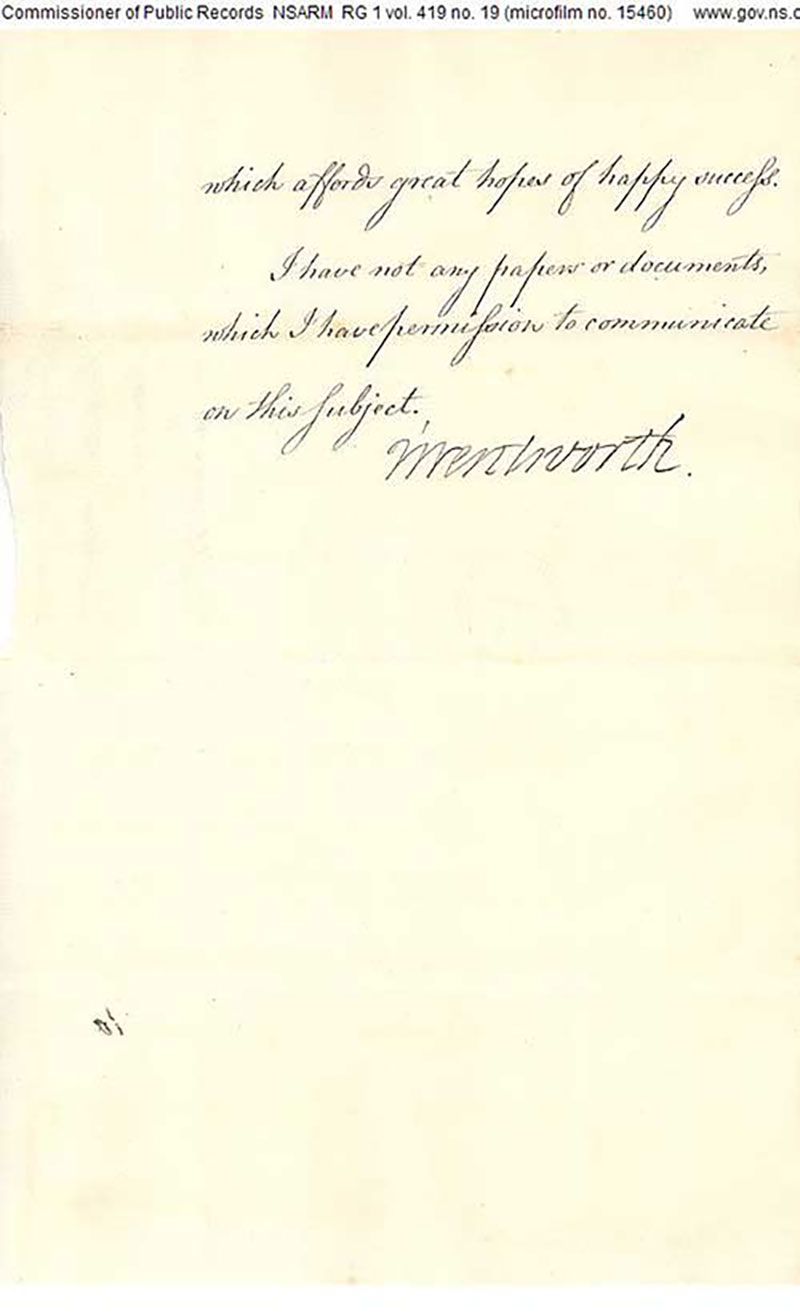

https://archives.novascotia.ca/Africanns/archives/?ID=53 - Lieutenant Governor Wentworth’s letter

https://archives.novascotia.ca/Africanns/archives/?ID=56 - Vice Admiral Cochran’s Proclamation

https://archives.novascotia.ca/Africanns/archives/?ID=70 - List of slaves on board HMS Rifleman

https://archives.novascotia.ca/Africanns/archives/?ID=69 - Melville Island military prison

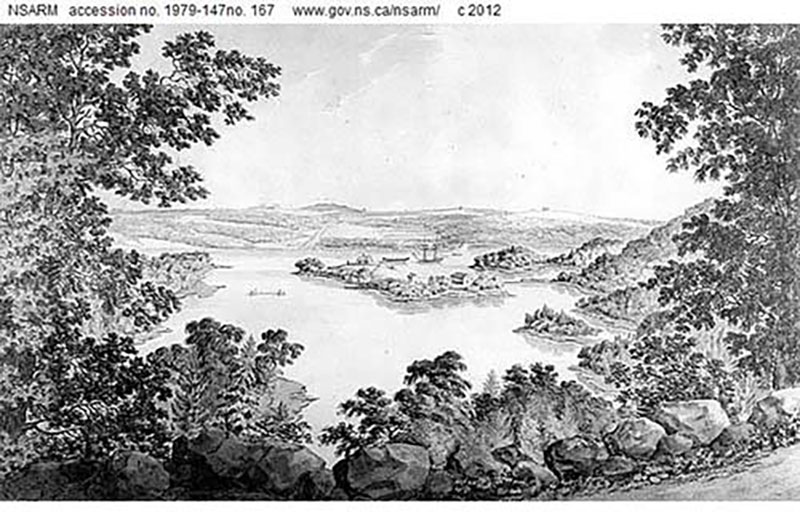

https://archives.novascotia.ca/Africanns/archives/?ID=72 - View of Melville Island from Cowie’s Hill

https://archives.novascotia.ca/Halifax/archives/?ID=6 - Health Officer’s Certificate

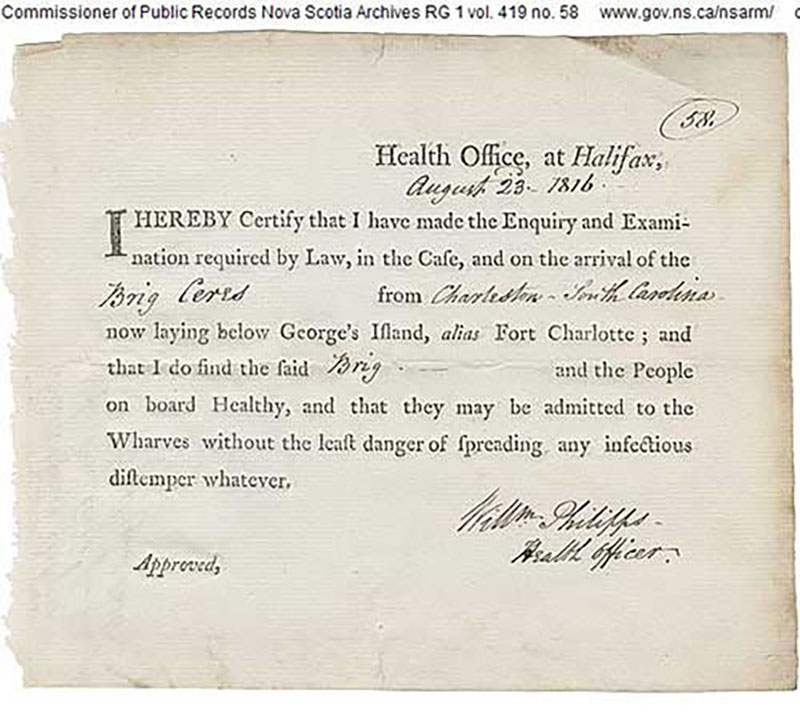

https://archives.novascotia.ca/Diaspora/archives/?ID=58 - List of Black Refugees on HMS Diadem

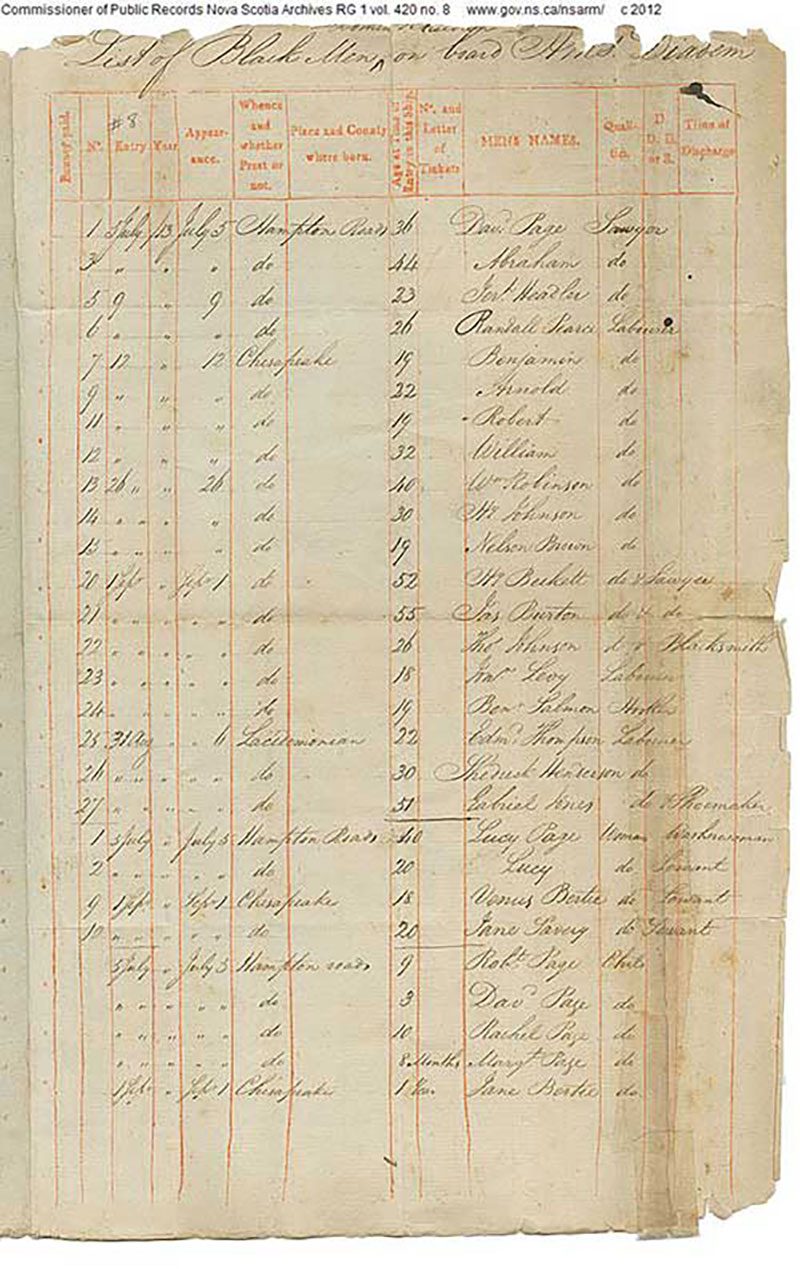

https://archives.novascotia.ca/Diaspora/archives/?ID=139 - Address of the House of Assembly

https://archives.novascotia.ca/Africanns/archives/?ID=76 - List of Black Refugees wishing to settle upon land at Preston

https://archives.novascotia.ca/Diaspora/archives/?ID=74 - Lots occupied by Black individuals at Preston

https://archives.novascotia.ca/Diaspora/archives/?ID=24 - Black Family near the Bedford Basin

https://archives.novascotia.ca/Africanns/archives/?ID=108 - List of Black Refugees at Beech Hill expressing a desire to settle in Trinidad

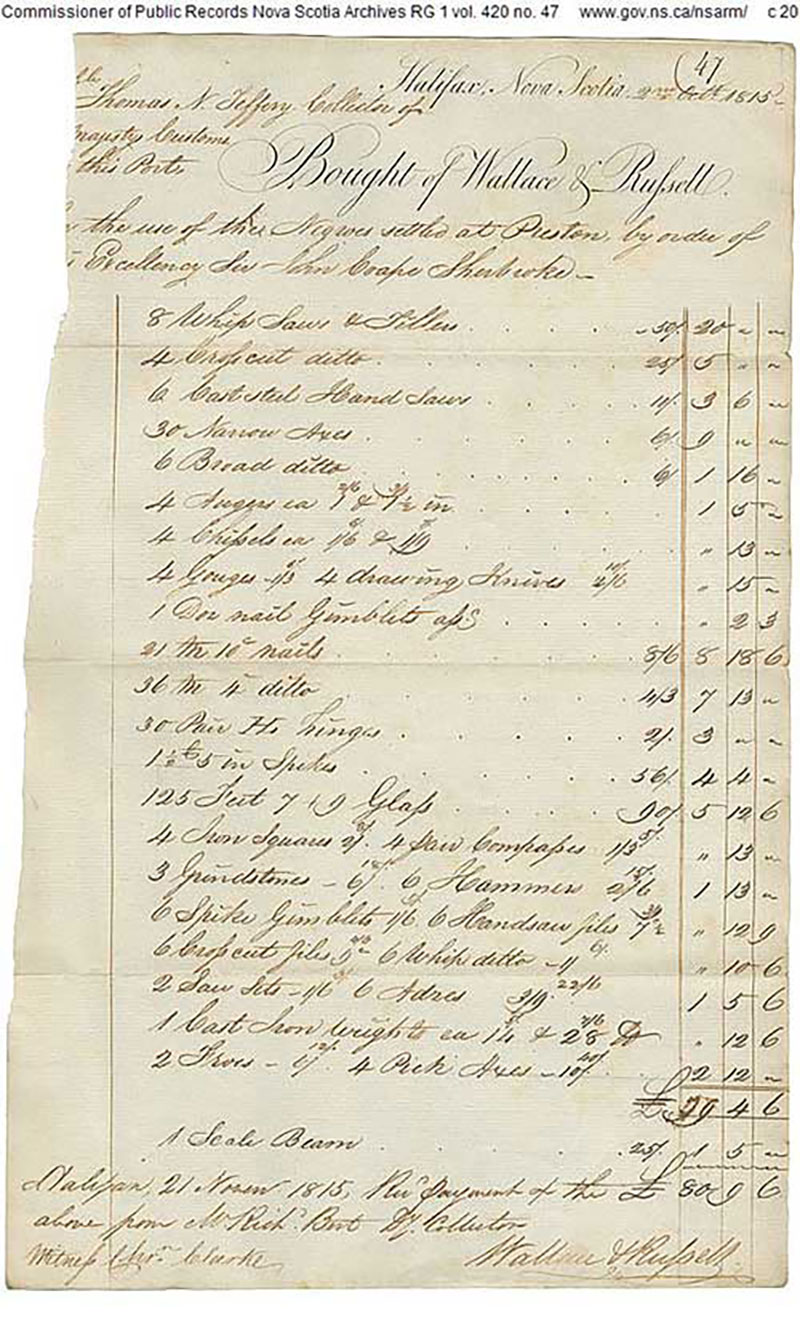

https://archives.novascotia.ca/Diaspora/archives/?ID=411 - Various accounts for supplies given to Black Refugees

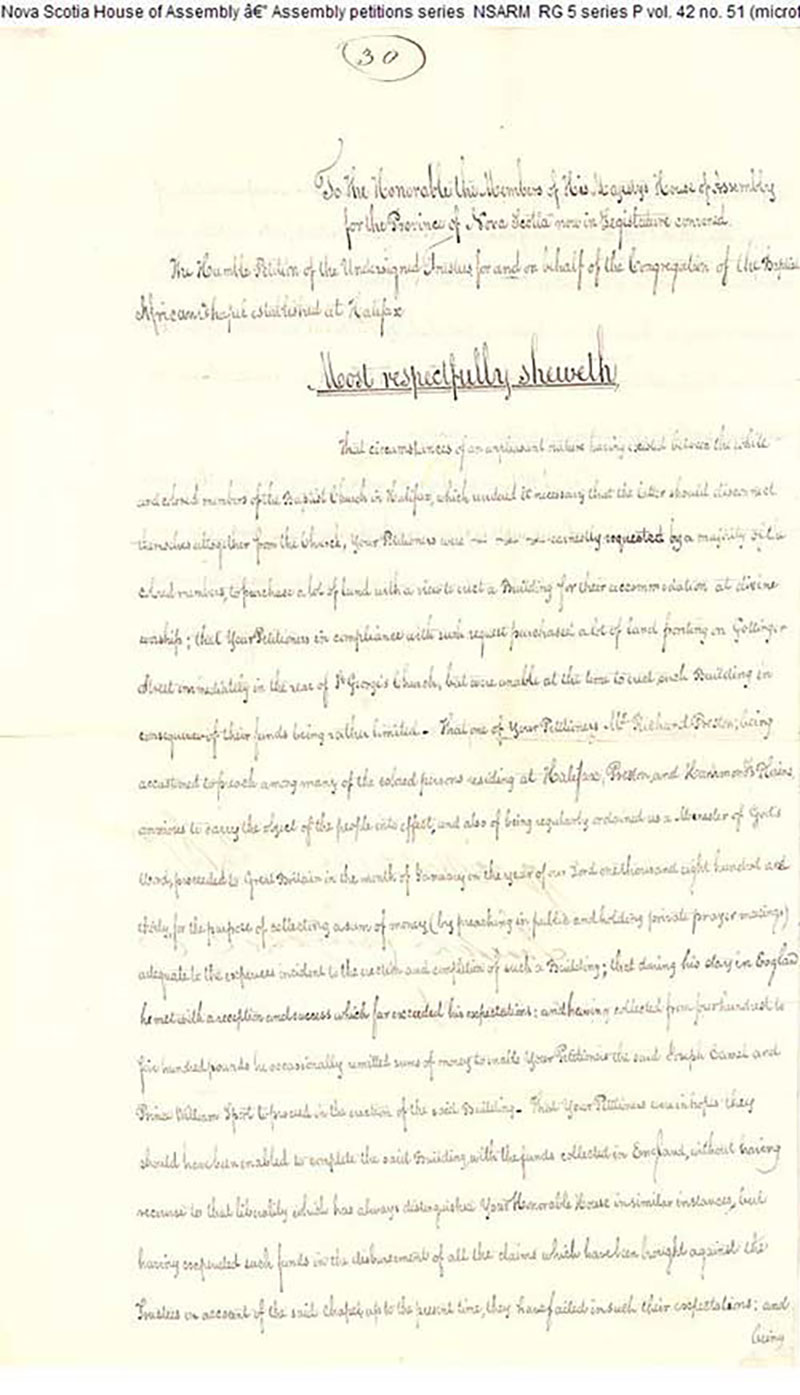

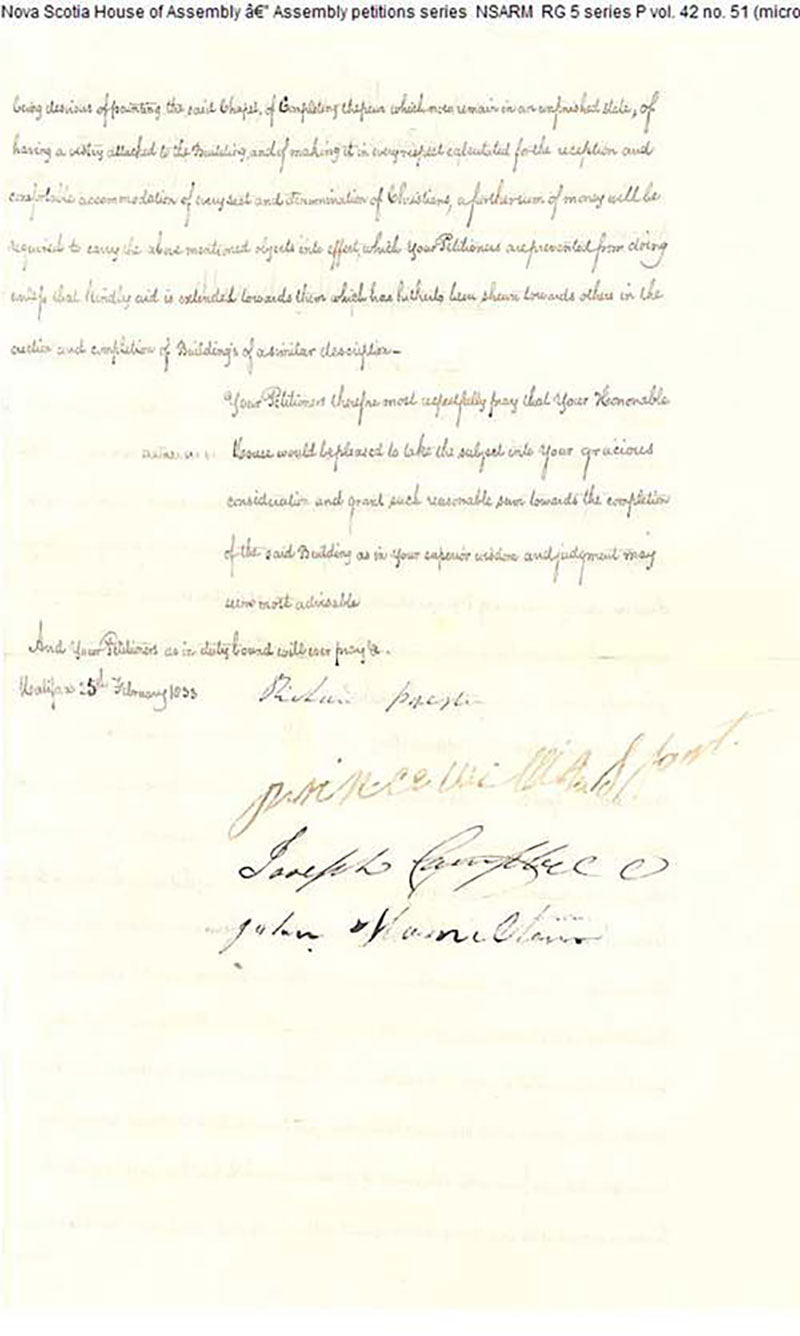

https://archives.novascotia.ca/Africanns/archives/?ID=178 - Petition from Richard Preston

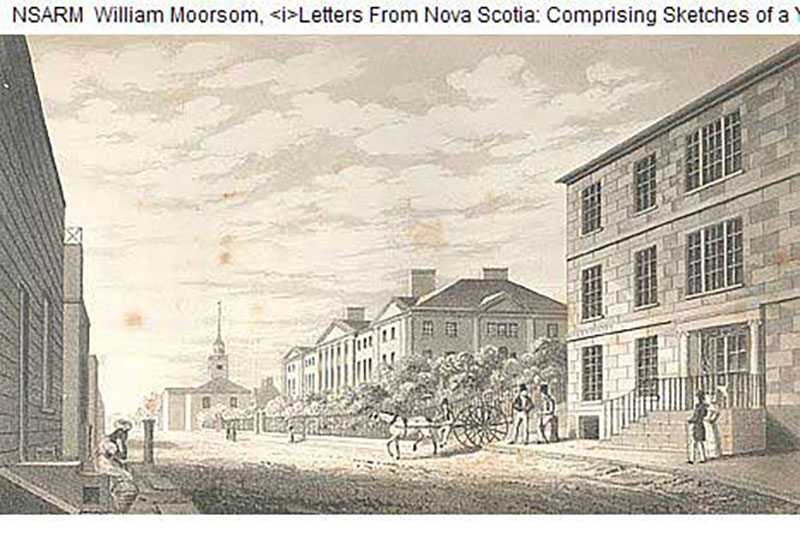

https://archives.novascotia.ca/Africanns/archives/?ID=103 - Engraving of Province House

https://archives.novascotia.ca/Africanns/archives/?ID=101 - Pencil sketch of unidentified Black man

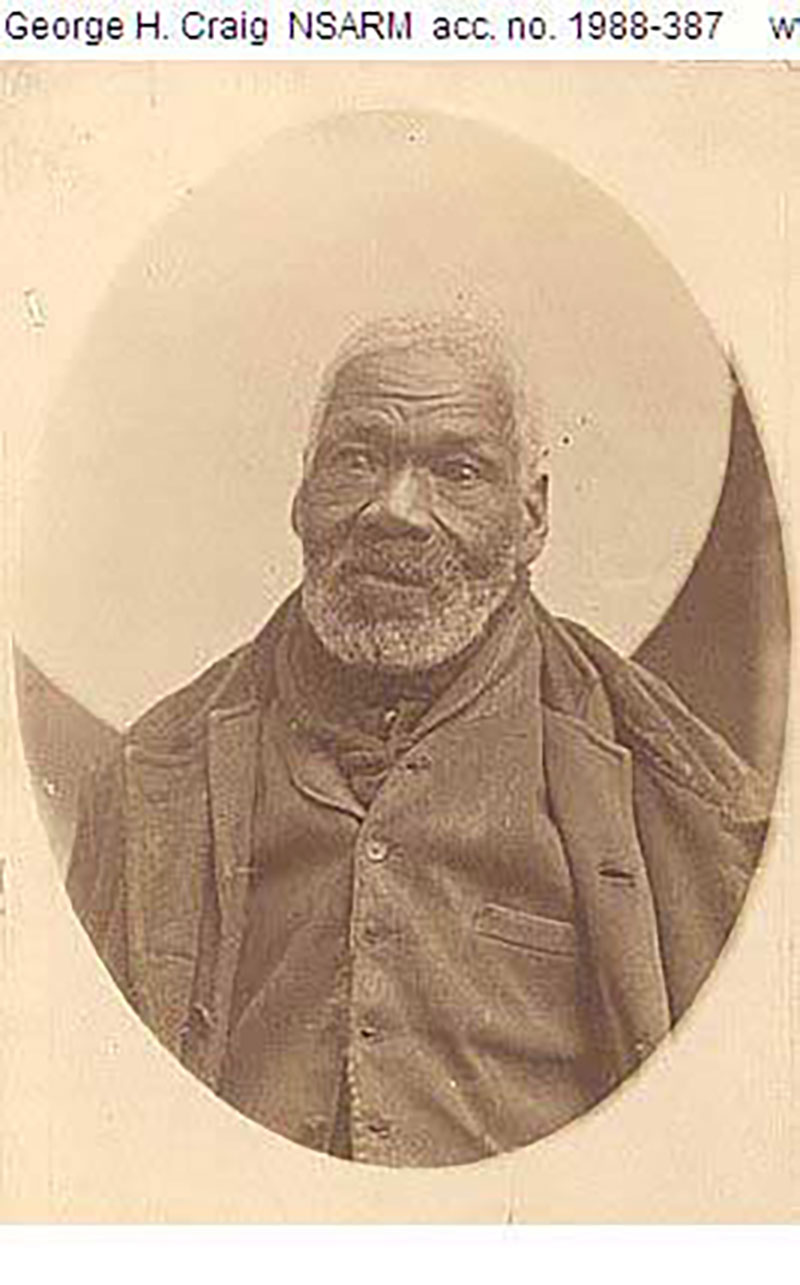

https://archives.novascotia.ca/Africanns/archives/?ID=112 - Gabriel Hall

https://archives.novascotia.ca/Africanns/archives/?ID=151 - William Hall

https://archives.novascotia.ca/Africanns/archives/?ID=152

- Harvey Amani Whitfield, “The Development of Black Refugee Identity in Nova Scotia 1813-1850,” Left History 10, no. 2 (Fall 2005): 10. ↩

- James W.St.G Walker, The Black Identity in Nova Scotia: Community and Institutions in Historical Perspective (Dartmouth: Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia, 1995), 10-11. ↩

- James W.St.G. Walker, The Black Loyalists: The Search for a Promised Land in Nova Scotia and Sierra Leone 1783-1870 (New York: Africana Publishing Co., 1976), 386, 388. ↩

- John N. Grant, “Black Immigrants into Nova Scotia, 1776-1815,” The Journal of Negro History 58, no.3 (July 1979): 258-261; Whitfield, “The Development of Black Refugee Identity,” 11. ↩

- Walker, The Black Loyalists, 388. ↩

- Harvey Amani Whitfield, Blacks on the Border: The Black Refugees in British North America, 1815-1860 (Burlington, Vermont: University of Vermont Press, 2006), 30.↩

- ”Admiral Cochran’s Proclamation,” 2 April 1814, Commissioner of Public Records Collection, Nova Scotia Archives and Record Management (hereafter NSARM), RG 1, Vol. 111, No. 99-100, Microfilm No. 15262, https://archives.novascotia.ca/africanns/archives/?ID=70↩

- Whitfield, Blacks on the Border, 32.↩

- “Sherbrooke to Bathurst,” 18 October 1813, Dispatches from Governors of Nova Scotia to Secretaries of State, NSARM, RG 1, Vol. 111, No. 66-37, Microfilm No. 15262.↩

- Harvey Amani Whitfield, “’We Can Do As We Like Here’: An Analysis of Self Assertion and Agency Among Black Refugees in Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1813-1821,” Acadiensis 32, no. 1 (Autumn 2002): 41.↩

- “Coleman to Sabathier,”23 March 1815, Correspondence and Other Material, NSARM, RG 5 A, Vol. 21, No. 84, Microfilm No. 15598.↩

- “Morris to Sherbrooke,” 6 September 1815, Commissioner of Public Records Collection, NSARM, RG 1, Vol. 420, No. 76, Microfilm No. 15464.↩

- Robin Winks, The Blacks in Canada: A History, 2nd ed. (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen`s University Press, 1997), 121, 125, 129;“Dalhousie to Bathurst,” 16 May 1817, Dispatches from Governors of Nova Scotia to Secretaries of State, NSARM, RG 1, Vol. 112, No. 23-25, Microfilm No. 15262.↩

- “Address of the House of Assembly to Lieutenant Governor Sherbrooke Opposing Black Refugee Immigration,” 1 April 1815, Journal of the House of Assembly 1815, NSARM, p. 107, Microfilm No. 3528. https://archives.novascotia.ca/africanns/archives/?ID=76↩

- “Kempt to Bathurst,” 16 October 1823, Lieutenant-Governor’s Letterbook, NSARM, RG 1, Vol. 113, No 82.↩

- “Kempt to Harrison,” 20 January 1822, Lieutenant-Governor’s Letterbook, NSARM, RG 1, Vol. 113, No 35-36.↩

- Walker, The Black Identity in Nova Scotia, 14-15.↩

- Whitfield, “The Development of Black Refugee Identity,” 16-17.↩

- Whitfield, Blacks on the Border, 74.↩

- Winks, 129-130.↩

- Walker, The Black Loyalists, 386.↩

- Whitfield, “The Development of Black Refugee Identity,” 19.↩

- Statistics Canada. Visible minority groups, 2006 counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, and census divisions (table), 2006 Census of Population. Last updated 6 October 2010. Accessed 24 March 2014. http://www12.statcan.ca/census-recensement. Aboriginal peoples are not included in statistics for visible minority populations because the Employment Equity Act defines visible minorities as “persons, other than Aboriginal peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour.” The 2006 census indicates that Nova Scotia has an Aboriginal population of 24,175 while the black population numbers 19,230.↩