by Jan Raska, PhD, Historian

Introduction

Canada is home to the fourth-largest Irish diaspora in the world.[1] According to the 2021 Canadian Census, 4,413,120 Canadians claimed full or partial Irish ethnicity. Within this population, 3,819,255 Canadians reported multiple origins, while 593,865 Canadians claimed only to be of Irish origin.[2] The Irish Canadian community comprises 11.9 percent of Canada’s total population.[3] These figures include Irish Canadians of all religious backgrounds and do not differentiate between the two largest denominations: Catholic and Protestant. Existing estimates that balanced census figures for origins and religion, indicate that by 1851, the Irish Catholic population in British North America (i.e. United Province of Canada (Canada West and Canada East), Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick)) numbered some 200,000 individuals. By 1861, this figure had grown to 280,000. In 1871, a few short years after Confederation, the Irish Catholic community in Canada numbered approximately 260,000 people, with onward migration accounting for this decrease.[4] While the Canadian Census does not currently cross-tabulate ethnocultural origin and religion, it did so with the 1931 Canadian Census in which one-third of the Irish population in Canada was Catholic and two-thirds was Protestant.[5] While these demographic patterns illustrate the scope and composition of the Irish presence in Canada, they only hint at the historical processes that shaped such a sizable diaspora. To fully understand the development of this community, it is necessary to examine the early movements of Irish migration to British North America and the socioeconomic and political forces that propelled them across the Atlantic.

Pre-20th Century Irish Migration to British North America

Significant Irish Catholic migration to British North America began in the 17th and 18th centuries, when many individuals arrived in Newfoundland to work as fisherman in an effort to escape poverty in their homeland.[6] Following the 1801 Act of Union, Ireland – a majority Catholic country – became controlled by Britain (majority Protestant) as part of the United Kingdom. Apart from six counties that constitute Northern Ireland, a majority of the Irish were Catholics who lived on small farms rented from English landlords.[7] From 1815 onwards, Irish migration to North America became more prevalent than in previous decades. Approximately 800,000 to 1 million individuals left Ireland between 1815 and 1846. Ireland’s growing population and deteriorating economy – Ireland’s textile industry, a significant source of employment, collapsed because it could not compete with Britain’s new production methods – forced a growing movement of Irish to emigrate to North America, particularly after 1815.[8]

The Irish (Catholic and Protestant) represented the single largest migrant group to settle in nineteenth-century Canada. Yet, most of them came before the Great Potato Famine. Between 1825 and 1845, some 450,000 Irish migrants arrived in British North America. Less than one-half of them were Catholic, and of the Protestant majority, most were Anglican. The necessary capital required to fund a journey across the Atlantic Ocean meant that mostly individuals from the largely commercial farming class with sufficient means undertook the voyage to a new land. They were not motivated by poverty and hunger as those subsequent arrivals of the late 1840s, but rather by fear as they stood to lose their economic status if they remained in Ireland. Upon arriving in British North America, most of these newcomers settled in rural areas and undertook agricultural work.[9]

Irish migrants began arriving in British North America’s east coast ports in large numbers. Towns in the British colony of New Brunswick, such as Newcastle, Chatham, and Miramichi, saw hundreds arrive before 1820. Many Irish newcomers were economically on the margins. At the time, the economies of British North America’s colonies were expanding, which offered Irish migrants better opportunities than at home. By the 1830s, the British colonies of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Upper Canada (Ontario), and Lower Canada (Quebec) had significant Irish populations. The Irish tended to remain in port cities such as Halifax, Saint John, and Montreal. Halifax was home to a large and permanent population by the middle of the 19th century. Irish migrants provided a source of cheap labour in the cities, as they often worked on public construction projects, such as the Rideau (Ottawa) and Lachine (Montreal) canals, and the Victoria Bridge in Montreal. Outside of urban areas, Irish newcomers established farms in rural counties.[10]

The year 1847, in which over 100,000 Irish emigrants left their homeland in search of refuge in British North America, remains a pivotal period in the history of the Irish community in Canada. Most settled in what would later become the Canadian provinces of Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. Approximately 70 percent of this movement of Irish were of Catholic background with the remaining 30 percent of Protestant background. These emigrants had fled their homeland due to poverty, disease, and hunger caused by the Great Potato Famine. The famine-era emigrants initially came to be defined in popular and scholarly literature as “destitute, shiftless, diseased, and Catholic.” They were also viewed as “helpless victims of forces beyond their control, forced to choose between migration or death” and uprooted to live in overcrowded, unsanitary, and violent urban ghettos of North America.[11] In recent decades, this inaccurate portrayal of the largely Catholic Irish emigrants of the mid-nineteenth century has been revised to include, for example, the Irish emigrant’s own agency over the events of the famine and their migration experience.[12]

An Gorta Mór: The Great Potato Famine or the Great Hunger?

How to label the catastrophic events of the widespread potato crop failures, starvation, migration, and death across Ireland in the mid-to-late 1840s remains contentious and sensitive today. Although these events are most often referred to as part of a famine, this remains a matter of some debate as scholars note that the ‘famine’ occurred in a country that, despite its concurrent economic problems at the time, was still at the centre of a growing British empire. With the resources of the United Kingdom, the consecutive years of potato blight in Ireland could have either completely or largely been mitigated by British officials. Within Ireland itself, there were substantial resources of food that, had the political will existed, could have been diverted, even as a short-term measure, to feed the starving population. At the height of these catastrophic events in 1847, the British Prime Minister, Lord John Russell, indicated his view of the situation:

It must be thoroughly understood that we cannot feed the people…We can at best keep down prices where there is no regular market and prevent established dealers from raising prices much beyond the fair price with ordinary profits.[13]

Discrimination against the majority Irish Catholic population took many forms. Political and economic power rested largely with the Protestant minority, which viewed Irish Catholics as inferior and backward. This religious difference soon became a moral justification for discriminatory treatment. British (Protestant) lawmakers often depicted the famine as a result of Catholic laziness, ignorance, or divine punishment rather than colonial exploitation or political failure. The Irish Catholic population was often racialized by the British newspaper industry who referred to the community as a “Celtic” race distinct from the “civilized” English, for example. In addition, a vast majority of Irish Catholic peasants were tenant farmers or landless labourers who rented or worked for Anglo-Irish Protestant landlords.

Given these ethnic, religious, and class differences in Ireland, discrimination against the Irish Catholic population at the hands of the British authorities and British landowners was widespread. As the Irish population grew considerably in this period so too did their poverty. By the mid-nineteenth century, potatoes, a vegetable brought to the island from the Americas became a staple of the Irish diet and helped to sustain many poor Irish families during the winter months and through periods of unreliable crop yields, including successive years of crop failures. The potato became a base food for the poor in Ireland. Land holdings were so small that that no crop other than potatoes would suffice to feed a family. The Great Potato Famine was caused by several factors including: overpopulation, decline in commercial farming, and the failure of the potato crop, which many individuals relied on for most of their nutrition. The Irish population relied on the potato as a nutritious, calorie-dense foodstuff that was easily grown on Irish soil. By the time of the Great Potato Famine, nearly half of Ireland’s population relied almost exclusively on potatoes for their diet. A disease known as Phytophthira infectans (late blight), a fungus destroyed the leaves and edible roots of the potato plants in successive years, between 1845 and 1852.

Credit: Civvi~commonswiki, Wikipedia Commons, 2005.

From Potato Blight to ‘Famine Food’ in Ireland

The potato blight struck for the first time in the eastern United States in the summer of 1843. The invisible fungus spores were then transported to Belgium in a cargo of apparently healthy potatoes, and in the summer of 1845, the fungus revived and devastated the potato crop in Belgium (Flanders), France (Normandy), Netherlands (Holland), and southern England. In August 1845, the blight was first recorded at the Dublin Botanical Gardens in Ireland, and a week later a total failure of the potato crop occurred in County Fermanagh. By October 1845, widespread panic had occurred in western Ireland as the blight destroyed healthy potatoes harvested in August. The potato blight would go on to cause a series of failed potato crops which brought about mass starvation. While the potato blight was the triggering event that destroyed food supplies, it did not directly cause deaths. Mass starvation led to a weakened, malnourished, and displaced Irish population which hastened the spread of cholera, typhus, body lice, fleas, among other conditions. Levels of personal hygiene among the Irish population remained low and the effects of the famine forced many individuals and families to abandon their homesteads for the country’s roads in search of work and or food. This produced a new term for these diseases during the famine: “road fever.”[14]

In order to stave off starvation and death, several species of edible algae, including dulse, channeled wrack, and Irish moss (Chondrus crispus), were eaten by coastal peasants during the famine. Further inland, famine foods included stinging nettle, wild mustard, sorrel, and watercress.[15] In the area of Skibbereen (County Cork), people resorted to eating donkey meat, earning the nickname “Donkey Aters” (Eaters) for people in the area.[16] Others ate dogs, cats, corncrakes, rotten pigs, and even human flesh.[17] In recent years, scholars have begun to examine what, if any, role cannibalism played in the Great Potato Famine. Irish historian, Cormac Ó Gráda asserts that “Cannibalism is one of our darkest secrets and taboos.”[18] He points out that

On the other hand, the relative ‘silence’ on cannibalism in Ireland during the 1840s is no proof that it did not happen. The taboo against cannibalism meant that, when and if it occurred, it would have been furtive, all traces hidden by the perpetrators. And the same taboo would have inhibited others from recalling it.[19]

While there are very few documented cases of cannibalism (documentation of a taboo is itself a problem), the consumption of silverweed, sea anemones, wild carrot, sloes, pignut, common limpet, snails, dock leaves, sycamore seeds, laurel berries, holly berries, dandelion, juices of red clover and heather blossoms have been recorded.[20] In Ireland, silverweed is known as ‘famine food’ because people returned to eating it in times when cultivated food was rare. Unlike many other ‘famine foods,’ silverweed (silverweed root or Potentilla anserina) has a tasty and nutty flavour. Many accounts of the Famine mention people dying with green stains around their mouths from eating grass or other green plants.

The subsequent deaths attributed to the potato famine and emigration overseas saw Ireland’s population decrease from 8 million inhabitants in 1841 to approximately 2 million by 1860.[21] The famine migration between 1845 and 1852 remains the largest contiguous movement of (predominantly Catholic) Irish to Canada. By 1871, the Irish constituted the largest ethnic group in every large town and city of Canada, with the exceptions of Montreal and Quebec City.[22]

Transatlantic Journey and Arrival in Nineteenth-Century British North America

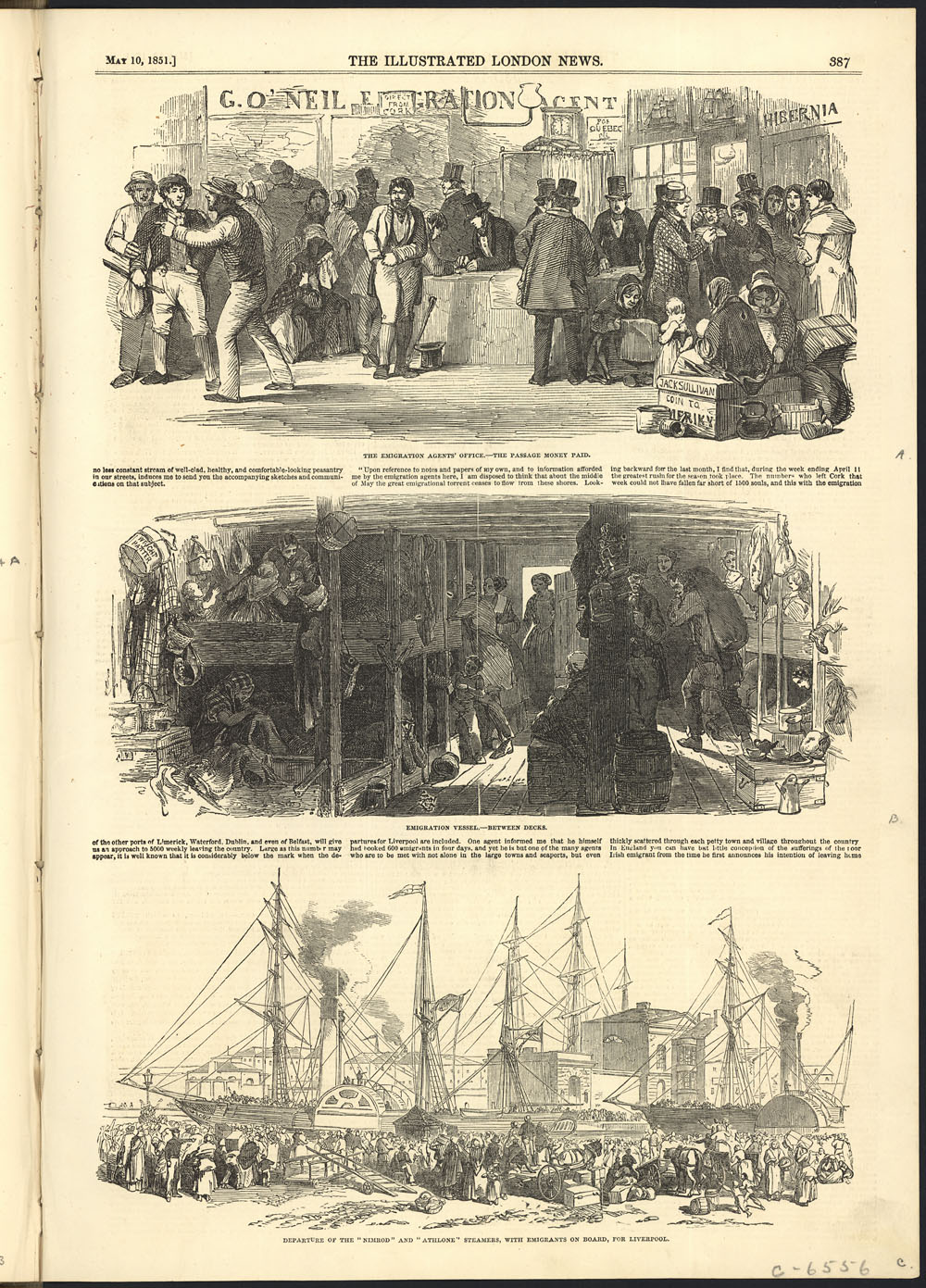

The majority Catholic Irish who emigrated to British North America during the Great Potato Famine of the 1840s did so without the same means as their earlier Protestant compatriots. On a typical transatlantic crossing, cargo was loaded first, then the cabin passengers and only when the ship was ready to sail could steerage passengers board. Most of the passengers had never been on a ship before. They were expected to bring their own food with them and cook it on the few grates provided aboard ship. The staple food of Irish emigrants on the ships was oatmeal and water.[23] The high levels of sickness and death can be attributed to overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, and a lack of food aboard the vessels transporting Irish emigrants to British North America.[24]

Credit: D.A. McLaughlin / Library and Archives Canada / C-006556.

Suffering from hunger and poverty, many died onboard ship due to diseases such as typhus, cholera, dysentery, fever, and smallpox. It is estimated that upwards of 20,000 Irish died of typhus onboard “coffin ships” headed towards British North America.[25] The largest port of entry for Irish emigrants into British North America was Quebec City and its Grosse Île Quarantine Station.[26]

Table 1: Arrivals at Grosse Île Quarantine Station, 1825-1847[27]

| Immigrants | Hospital Admissions | Deaths | Cholera | Fever & Dysentery | Smallpox | Other |

| 425,490 | 14,533 | 3,934 | 290 | 4,648 | 722 | 726 |

| Immigrants | 425,490 |

|---|---|

| Hospital Admissions | 14,533 |

| Deaths | 3,934 |

| Cholera | 290 |

| Fever & Dysentery | 4,648 |

| Smallpox | 722 |

| Other | 726 |

Following Grosse Île, Saint John, New Brunswick’s Partridge Island Quarantine Station also processed a large movement of Irish emigrants in the 1840s. During the period 1840-1847, some 59,200 newcomers arrived in New Brunswick, of which 88 percent were of Irish origin. A majority of these individuals landed at Saint John. In 1845-1847, most of the arrivals were sick with typhus and smallpox, which created a public health emergency as the city’s population totalled more than 30,000 residents (32,957 in 1840), of which some 19,000 of them lived in the city proper. Yet, at the height of the Great Potato Famine in 1847, around 2,000 Irish emigrants were quarantined on Partridge Island during a typhus epidemic. Of these newcomers, 601 were buried later in a mass grave on the island. From March 1847 to March 1848, 2,381 Irish emigrants and a further 610 paupers were admitted to the city’s Almshouse establishment, including emigrant hospitals and sheds. Of this population, 560 emigrants and 126 paupers later died from disease in that year alone. The mass arrival of predominantly Irish emigrants created havoc throughout Saint John.[28] Many of the Irish passengers that entered British North America through Saint John eventually settled in either New Brunswick, the United Province of Canada, or continued on to the United States.

Credit: D.A. McLaughlin / Library and Archives Canada / C-079029.

Irish newcomers with a farming background left the port areas of Quebec City, Montreal, Saint John, or Halifax for rural locations: the Ottawa Valley in Canada West, Beauharnois and Lotbinere in Canada East, as well as inland in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. However, most Irish emigrants tended to settle in cities as they offered a greater chance of securing much needed employment.[29]

Conclusion

Irish migration to British North America profoundly influenced Canada’s demographic and cultural development. From early settlers in the seventeenth century to the mass exodus during the Great Potato Famine, Irish migrants—both Catholic and Protestant—formed one of the largest and most significant ethnic communities in nineteenth-century Canada. The famine-era migration, driven by poverty, disease, and political neglect, resulted in immense suffering but also demonstrated the resilience of those who endured perilous transatlantic journeys and harsh quarantine conditions.

Despite initial hardship and widespread discrimination, Irish migrants played a crucial role in shaping Canada’s emerging social and economic landscape. They contributed to the growth of urban labour forces, agricultural settlement, and community institutions that became integral to Canadian society. The legacy of Irish migration thus reflects both the tragedy of displacement and the enduring capacity for adaptation and nation-building. Today, the prominence of Irish ancestry in Canada attests to the lasting impact of this migration on the country’s identity and historical development.

- “Irish diaspora,” Wikipedia, n.d. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irish_diaspora. See “List of countries by population of Irish heritage.” Canada is fourth on this list after the United States, Britain, and Australia.↩

- Statistics Canada, “Ethnic or cultural origin by generation status: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts,” Data Table 98-10-0338-01, October 26, 2022, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=9810033801.↩

- See Statistics Canada, “Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population,” https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?LANG=E&GENDERlist=1,2,3&STATISTIClist=1&HEADERlist=1&SearchText=Canada&DGUIDlist=2021A000011124. This figure was calculated by dividing the total Canadian population (36,991,981) by the number of Canadians of Irish origins (4,413,120).↩

- Daniel Conner, “The Irish-Canadian; Image and Self-Image” (M.A. thesis, University of British Columbia, 1976), 1.↩

- Garth Stevenson, “Irish Canadians and the National Question in Canada,” in Irish Nationalism in Canada, ed. David A. Wilson (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2009), 165.↩

- Peter Toner and Gillian I. Leitch, “Irish Canadians,” Canadian Encyclopedia, last edited January 26, 2018, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/irish.↩

- Canadian Institute for the Study of Antisemitism, “Unit 4: Immigration, Migration, Refugees: Chapter 3: Italian and Irish Immigration,” Voices into Action, n.d., https://www.voicesintoaction.ca/lessons/unit4/chapter3/. See section “Irish Immigration to Canada in the 19th century: This Really Happened: The Great Hunger (The Irish Famine).”.↩

- “The fascinating history of Irish emigration to Canada,” Irish Post, February 25, 2022, https://www.irishpost.com/history/the-fascinating-history-of-irish-emigration-to-canada-230370.↩

- Iacovetta, Draper, and Ventresca, “Topic One: The Irish in Nineteenth-Century Canada: Class, Culture, and Conflict,” 3.↩

- Toner and Leitch, “Irish Canadians;” Belshaw, Canadian History, 368.↩

- Franca Iacovetta, Paula Draper, and Robert Ventresca, “Topic One: The Irish in Nineteenth-Century Canada: Class, Culture, and Conflict,” in A Nation of Immigrants: Women, Workers, and Communities in Canadian History, 1840s-1960s, eds. Franca Iacovetta, Paula Draper, and Robert Ventresca (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997), 3.↩

- See for example, Mark McGowan, Creating Canadian Historical Memory: The Case of the Famine Migration of 1847 (Ottawa: Canadian Historical Association, 2006), 2.↩

- Quinnipiac University, “Learn About the Great Hunger,” Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum, https://www.ighm.org/learn.html.↩

- Powderly, “How Infection Shaped History: Lessons from the Irish Famine;” Quinnipiac University, “Learn About the Great Hunger;” Doreen McBride, The Little Book of Fermannagh (Dublin: THP Ireland, 2018); Arthur Green, ed. The Great Famine and the Irish Diaspora in America (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press), 31; A.T. Lucas, “Nettles and charlock as famine food,” Breifne: Journal of Cumann Seanchais Bhreifne 1.2 (1959): 137-146.↩

- Powderly, “How Infection Shaped History: Lessons from the Irish Famine;” Quinnipiac University, “Learn About the Great Hunger;” McBride, The Little Book of Fermannagh; Green, ed. The Great Famine and the Irish Diaspora in America, 31; A.T. Lucas, “Nettles and charlock as famine food,” 137-146.↩

- Gary Connaughton, “Here’s the explanation behind some of the weirdest Irish County Nicknames,” Balls.ie, February 20, 2020, https://www.balls.ie/irishlife/irish-county-nicknames-426562.↩

- Ronan McGreevy, “Role of ‘survivor cannibalism’ during Great Famine detailed in new TV documentary,” Irish Times, November 30, 2020, https://www.irishtimes.com/news/ireland/irish-news/role-of-survivor-cannibalism-during-great-famine-detailed-in-new-tv-documentary-1.4423323; Donal MacNamee, “New RTE documentary finds evidence of cannibalism in four Irish counties during Great Famine,” Irish Mirror, November 30, 2020, https://www.irishmirror.ie/tv/new-rte-documentary-finds-evidence-23092963.↩

- Cormac Ó Gráda, “Eating people is wrong, and other essays on famine, its past, and its future,” ResearchGate (January 2015), 1. See https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282242649_Eating_people_is_wrong_and_other_essays_on_famine_its_past_and_its_future.↩

- Ó Gráda, “Eating people is wrong, and other essays on famine, its past, and its future,” 30.↩

- Cathal Poirteir, Famine Echoes: Folk Memories of the Great Irish Famine: An Oral History of Ireland’s Greatest Tragedy (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan Ltd., 1995); Maureen Langan-Egan, “Some Aspects of the Great Famine in Galway,” Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society 51 (1999), 120-139; Vivienne Campbell, “Edible and Medicinal Herbs,” Vegan Sustainability Magazine, n.d., http://vegansustainability.com/edible-and-medicinal-herbs/.↩

- William G. Powderly, “How Infection Shaped History: Lessons from the Irish Famine,” Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association 130 (2019): 127-135, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6735970/; Joel Mokyr, “Great Famine,” Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d., https://www.britannica.com/event/Great-Famine-Irish-history; Canadian Institute for the Study of Antisemitism, “Unit 4: Immigration, Migration, Refugees: Chapter 3: Italian and Irish Immigration.” See section “Irish Immigration to Canada in the 19th century: This Really Happened: The Great Hunger (The Irish Famine).”↩

- “The fascinating history of Irish emigration to Canada.”↩

- “Irish Emigration to America – The Journey,” National Museum of Ireland, n.d., https://www.museum.ie/en-IE/Collections-Research/Folklife-Collections/Folklife-Collections-List-(1)/Other/Emigration/Irish-Emigration-to-America-The-Journey.↩

- André Charbonneau and André Sévigny, Grosse Île: A Record of Daily Events (Ottawa: Canadian Heritage, 1997), 14.↩

- Canadian Institute for the Study of Antisemitism, “Unit 4: Immigration, Migration, Refugees: Chapter 3: Italian and Irish Immigration.”↩

- See Marianna O’Gallagher, Grosse Ile: Gateway to Canada, 1832-1937 (Ste. Foy: Livres Carraig Books, 1984).↩

- See Canadian Institute for the Study of Antisemitism, “Unit 4: Immigration, Migration, Refugees: Chapter 3: Italian and Irish Immigration.” See section “Irish Immigration to Canada in the 19th century: This Really Happened: The Great Hunger (The Irish Famine).”↩

- Harold E. Wright, “Partridge Island: ‘Canada’s Emerald Isle’ ‘A Gateway to North America,’” Irish Canadian Cultural Association of New Brunswick, 2008, https://newirelandnb.ca/quarantine-stations/partridge-island; Parks Canada, Directory of Federal Heritage Designations, “Partridge Island Quarantine Station National Historic Site of Canada,” n.d., https://www.pc.gc.ca/apps/dfhd/page_nhs_eng.aspx?id=191#:~:text=During%201847%2C%202000%20Irish%20immigrants,Canada%20and%20the%20United%20States; James M. Whalen, “Almost as Bad as Ireland: The Experience of the Irish Immigrant in Canada, Saint John, 1847,” Irish Canadian Cultural Association of New Brunswick, n.d., https://newirelandnb.ca/culture/irish-trail/early-settlement/almost-as-bad-as-ireland-the-experience-of-the-irish-immigrant-in-canada-saint-john-1847.↩

- CMI, Core Exhibition report, “3.5 - Where To Live?” [internal document], July 31, 2015, Reviewed January 26, 2017.↩