by Daniel Meister, PhD

Introduction: The Context of Colonialism

“Let us take possession of Canada. Let our cry be CANADA FOR THE BRITISH.”

- Isaac Barr[1]

At the turn of the twentieth century, the two largest groups of immigrants to Canada by nationality were Americans and British. British agriculturalists were viewed by many Canadians as the most desirable settlers, so these numbers were reassuring to them.[2] Many British people shared this feeling, as they wanted to see their colonies settled with British immigrants in order to keep them firmly within the Empire.

Of course, there were still some British people throughout the Empire who wished for British settlers to form an even larger percentage of all immigrants to the colonies. The town of Lloydminster, which straddles the border of Alberta and Saskatchewan, was established as a result of this sentiment. Originally known as the “Barr Colony” (later the “Britannia Colony”), it was founded in 1903 as an all-British settlement.[3].

The Barr colonists were likely unaware of the specific history of the lands they came to settle. However, all of them were entangled in – and active agents in the advancement of – the broader project of British settler colonialism. Before the history of the colony is traced, it is important to understand this settler colonial context.

For thousands of years prior to the arrival of Europeans, the land on which the colony was eventually established had been inhabited by Indigenous peoples, specifically the Nehiyawak or Plains Cree.[4] In 1670, King Charles II of England claimed ownership of this land, which the English called Rupert’s Land. This vast area that represented a third of the territory that came to be known as Canada, stretching across what is now Quebec to Alberta and as far north as the Northwest Territories. That same year, Charles II granted a Royal Charter to the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), declaring them “the true and absolute Lords and Proprietors” of the land. Almost two centuries later, in 1868, the HBC sold the land to the newly confederated Canada, though the transfer did not come into effect until 1870.

But Charles II, nor the HBC, nor the Canadian federal government had acquired title to the land from the Nehiyawak. In fact, the land where the Barr Colony was established was not even covered by treaty until 1876, with the signing Treaty 6. The Indigenous signatories were interested in signing a treaty to share land and resources in order to protect lands from settlement, but also were motivated more directly by “the imminent collapse of the buffalo-hunting economy and their changing relationship with the HBC.” The federal government used starvation to coerce hold-outs, such as by deliberately withholding rations from the starving Nehiyawak clan led by Mistahimaskwa (Big Bear) until he signed Treaty 6 in 1882.

The text of Treaty 6 declared that the lands were ceded to the Dominion of Canada. However, it is unclear to what extent the text was verbally communicated to the Indigenous signatories. As a result, and ever since the signing, there have been disagreements about the meaning and intentions of the treaty’s terms.[5] The treaty also assigned various reserves of land to different bands, two of which were forced to amalgamate into the Onion Lake Band in 1914; their reserve is located about fifty kilometres north of what is now Lloydminster.[6]

This history was likely not known to many of the colonists or their leaders, the Canadian-born Isaac M. Barr and later the British-born George E. Lloyd. Both were Anglican clergymen and the specific ideas about empire, gender, and religion that they held were instrumental in shaping their colonial endeavours. These ideas were also shared by some Canadian authorities, which helps to explain why the Barr Colonists received different treatment than their Cree neighbours.

A Dreamer Turned Leader: Isaac Barr

In 1847, Isaac Montgomery Barr was born in what is now Halton Hills, Ontario. His parents were Irish immigrants, his father a Presbyterian minister and his mother a homemaker. Little is known of his early years. Although his father bought a piece of farmland for him and his brother Jack in order that they might settle down, both sold their plots of land and left: Isaac sailed to Ireland while Jack headed to western Canada, where the two would later reunite. In Ireland, Isaac sought out his family roots and spent much time in the company of his great-uncle, Captain John Baird, who had been present at the well-known Battle of Trafalgar. Baird must have appreciated the company for, when he died, he left Barr with an inheritance. He also instilled in him “the belief that he too had a part to play in the great tide of British expansion, that he too would be an empire builder.”[7]

Barr then returned to Canada, studied theology, married, and entered the Christian ministry (within the Anglican denomination). His initial religious career was quite varied. According to Helen Evans Reid, his sympathetic biographer, his troubles at numerous early parishes stemmed from his lack of humour, unwillingness to accept lower wages, and his controversial theological opinions, including a belief in evolution. After a brief falling-out with his superiors, he eventually apologized and pledged his belief in the Church’s teachings. He and his growing family then moved to the United States where Barr continued his religious career for twelve years. This was evidently a similarly eventful period, as he divorced, remarried, then remarried a third time, all the while continuing to serve as a priest.[8]

In 1901, Barr was inspired by the wide press coverage of Cecil Rhodes' African colonization schemes.[9] He thus announced his intentions to quit his ministry and move to South Africa to pursue a settlement scheme with Rhodes, with the first step being a move to England to recruit settlers. However, this was probably never more than a dream in Barr’s mind as no evidence of correspondence between the two men has ever been found.

Although Rhodes’ death in 1902 likely put a definitive end to Barr’s plans for South Africa, he may had been considering other locations even before this, as he had already been corresponding with the Canadian Commissioner for Immigration in London seeking employment as an immigration officer. Upon being informed they did not have any vacancies, he found work as a minister in London. At the same time, he launched a campaign promoting Canadian colonization by writing scores of letters, giving interviews, and delivering public addresses. In all of these venues, he emphasized that Canada offered an escape from poverty and a chance to build the empire by “planting a colony of pure British culture.”[10]

Barr’s initial plan, which he pitched to Canadian immigration officials in London, was to take 25 families who had agricultural skills and to help them immigrate to Canada, where they would form the heart of a new, all-British colony on the Canadian prairies that would in turn attract more British immigrants. In August 1902 Barr prepared a pamphlet to help publicize the idea, and the Commissioner of Immigration, W.T.R. Preston, agreed to pay for its publication. Barr then used this to argue that the federal government officially endorsed his plan, though they did not.[11]

The modest number of settlers soon mushroomed: by September 6, fifty people had agreed to go; by September 8, Barr had received over two hundred inquiries; and by September 22 interest had grown so much that he was planning to travel to Canada to make preliminary arrangements. Yet on that very day, a letter appeared in a London newspaper encouraging British immigration to Canada, signed by a Rev. George E. Lloyd. Keen for assistance, Barr wrote to Lloyd, stating that he was also working on a colonization plan, and asked for a meeting. Lloyd evidently agreed and the two met at some point before the end of the month.[12] But just who was this Rev. Lloyd?

The “Fighting Bishop”: G.E. Lloyd

George Exton Lloyd was born in Britain but, like Barr, little is known of his early years. His family moved repeatedly owing to his father’s work as a teacher, and Lloyd eventually enrolled in college in London, intending to use the education to apply for army officer training. At this point he already had the beginnings of a successful military career: he had enrolled with a volunteer regiment and risen to the rank of sergeant by the age of nineteen. However, a speech by a visiting Canadian bishop changed his life’s path.

In June 1865, Rev. Robert Machray delivered the Ramsden Sermon at Cambridge University. The Ramsden Sermon was an annual address dedicated to “Church Extension over the Colonies and Dependencies of the British Empire.” Machray was about to be appointed Bishop of Rupert’s Land and, in his sermon, he spoke of the territory to which he was about to travel and of its special needs, intending for his words to promote interest in missionary work. He got at least one passionate recruit: Lloyd, after hearing the message, abandoned his plans for a military career and decided to sail for Canada and pursue a life in the Christian ministry. However, as his biographer Chris Kitzan notes, “there remained echoes of a British army sergeant in many of the approaches he took in his new position.”[13]

Lloyd arrived in Canada in 1881 and stayed at his first mission only briefly before heading to Toronto, where he enrolled at Wycliffe College and joined a militia unit, the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada. When the North-West Resistance/Rebellion broke out in 1885, he volunteered to be mobilized. His unit was posted to Battleford and was led by General Otter. During a subsequent unauthorized and successful attack on a group of Cree and Assiniboine people (the Battle of Cut Knife), Lloyd was seriously wounded while attempting to extract some other soldiers who were pinned down and was later decorated for his efforts. In part due to his newfound fame, he was subsequently ordained as deacon by the very Bishop who had inspired him to come to Canada.[14] He spent two years recovering, during which time he married an Englishwoman named Marion Tuppen, whom he had known prior to moving to Canada. In 1886 he accepted a position as Chaplain of a boy’s reformatory in Ontario. After a falling out with his superiors, he relocated to become Rector of St. Paul’s Parish in Rothesay, NB. While there, he transformed a tiny private school into an Anglican boarding school for boys (now the Rothesay Netherwood School). The school was a success and for his efforts he was awarded an honorary doctorate from UNB in 1894, a rare distinction in that period. The following winter he suffered a breakdown, which he attributed to his wartime injuries and extensive administrative duties, but it was likely also due to conflict with prominent people in the area.[15]

The next two years saw him travel south and preach in the southern United States as well Jamaica before returning to Canada in 1898 to become editor of the Anglican Church’s newspaper, the Evangelical Churchman. This proved short-lived, for in 1900 he returned to England to work for the Colonial and Continental Church Society (CCCS), where his job was simply to promote emigration to Canada.

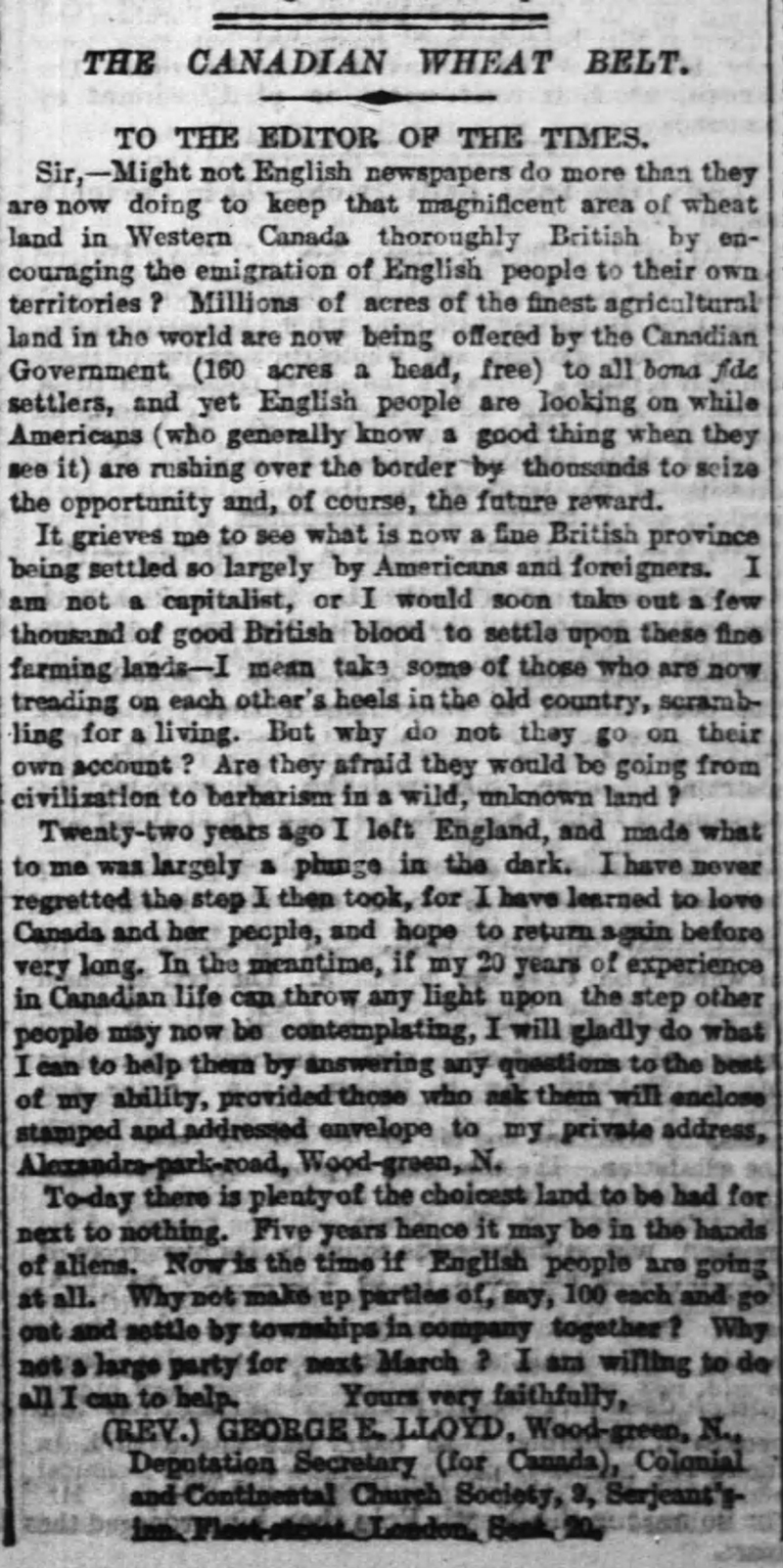

Lloyd approached the task with typical zeal and, according to his own account, over the next two years he preached 147 sermons and addressed over 700 meetings, all on the topic “The Expansion of Canada.” These attracted wide attention, especially from disillusioned Boer War veterans. He then had a letter published in the London Times, which was subsequently reprinted in a number of other papers and received thousands of replies – far more than he had ever anticipated – including a letter from one similarly-minded clergyman, Isaac Barr.[16]

Credit: George Exton Lloyd, “The Canadian Wheat Belt,” The Times [London] (22 September 1902), 8. Reproduced with permission from Newspapers.com.

Scouting in Saskatchewan and Recruiting in London

The meeting between the Anglican ministers was apparently a success. The two agreed to work together, so Lloyd supplied Barr with his list of potential colonists (that is, all those who had replied to his published letter).[17] Barr subsequently issued his pamphlet, entitled British Settlements for North-Western Canada on Free Grant Lands: Canada for the British, and had established himself in an office near to Lloyd. Historians have since noted that it is unclear where Barr got his information about the west but that much of what he printed was “excessively optimistic and even dangerously misleading.”[18]

At the end of the month, Barr sailed for Canada to select a site and make arrangements. Lloyd stayed behind at the office with their secretary and typist, fielding questions and conducting personal interviews of potential colonists, exhorting them: “If you are healthy, go, go, go west. If you are strong, go west. If you have a hundred pounds then go west!”[19]

Barr’s actions had thus far done little to endear him to officials at the Department of the Interior (then in charge of immigration) whom he was to meet in Canada. In addition to falsely claiming that his plan was officially endorsed by the Department, he had begun telling prospective colonists that they could forward any required fees to the Department’s London office where they would be held in trust. This led to the Acting Commissioner of Immigration in London to caution Barr: “I presume you have [the Commissioner’s] consent to act in this way, as otherwise it identifies him and the government with yourself and your colonisation scheme in a way that is misleading,” adding that the Commissioner ought to at least have “an opportunity of considering the matter before you commit him in print.”[20]

Despite his tactics, Barr succeed in convincing the government to reserve sixteen townships for the British colonists, though the Department made it clear that they would not be held indefinitely.[21] As word of this new project spread across the Prairies, the settler attitude was one of “curious optimism, tempered by many memories of the hardships of settlers in other years.” Some officials, however, feared Barr had bitten off more than he could chew; little would come of his schemes, they predicted. Others pointed to practical issues with his plan, such as the early date of arrival, when the weather would be cold and damp. Barr was eventually convinced to delay his departure, however, the remote location of the proposed settlement – about 240 kilometres from Saskatoon, with no railway access – remained unchanged.[22]

Barr Returns to England and Canadian Officials Begin to Plan

When Barr returned to England, he published an overview of his trip in a second pamphlet, this one entitled British Settlements in North Western Canada on Free Grant Lands: Canada for the British. Report of my Journey to the Saskatchewan Valley, N.W. Canada to Select Land for the First British Settlement. As historian Eric Holmgren puts it, “This interesting and rather curious document of some twenty-eight pages is in the form of a long and rather rambling letter. Barr may have intended to set it out in logical form but the result indicates that he simply set down his ideas as they came to him and made little or no attempt at an orderly revision.” He adds that a discerning reader would have concluded that Barr was neither systematic nor businesslike.[23]

Barr’s pamphlet ended with a dramatic call for action: “Britons have ever been great colonizers. Let it not be said that we are the degenerate sons of brave and masterful sires.” Apparently, this call resonated with some colonists; when later asked why he came to Canada, one colonist reportedly replied: “Why, to claim Canada for the bloomin’ Hempire.”[24]

By this time, Department officials and some of the more skeptical Prairie press had begun to worry that Barr had not made sufficient preparations. Immigration officials were determined to not have the colonists fail, as this would discourage future British immigration, so they began making contingency plans.[25] Barr, however, was rather belatedly making further plans of his own. As he had never obtained adequate financing for his project, he was constantly coming up with new ways to get money from prospective colonists.

Specifically, only months before the group was to sail, Barr issued circulars announcing the creation of a number of cooperatives (or “syndicates,” as he called them), one for supplies and one for transportation from the end of the railway to the reserved land, as well as a plan for a hospital and another to prepare the land for late arrivals. Most of these plans either did not come to fruition or did not last.[26] Some of his group were skeptical from the outset. Reflecting on his decision-making process, one such colonist remarked:

I rather liked Lloyd, he did not make light of the undertaking ahead of the party, but Barr appeared eager to advise everybody to invest in his numerous schemes … I came to the conclusion, rather than pay Barr for the necessary equipment for the journey I would provide my own.[27]

Anticipating that Barr was not going to have made adequate preparations, and that not all colonists would have sufficient supplies or experience, the government arranged to rent a building in a nearby community to serve as an immigration hall, appointed a sub-land agent to help with the settlement, and hired two farmers to instruct the considerable number of inexperienced colonists who would soon be arriving. For the trip between the end of the tracks and the settlement, the government hired guides and a surveyor. They also equipped rest sites at regular intervals with tents, stoves and firewood, as well as hay for the animals every 24 kilometres, near to a supply of water.[28]

The government’s skepticism was warranted. Although Barr repeatedly promised that nearly all of the colonists were experienced farmers, only 22 percent of the nearly 2,000 colonists who would sail to Canada on SS Lake Manitoba listed occupations relating to agriculture. This included not only farmers, but also “dairy and poultry breeders, as well as farm labourers, nurserymen, market gardeners, livestock breeders and cattle dealers. There were others with relevant trade skills like butchers, blacksmiths, carpenters, and labourers like railway employees.” The oldest colonist was 69 years old, while the mean age was mid-twenties.

As one historian put it, the “great majority” of the colonists were from the towns and cities of Britain and had no farming experience. The doctors found that their early days were spent bandaging colonists’ self-inflicted axe wounds, as most were unfamiliar with the tool. The two farming instructors hired by the government certainly had their hands full.[29]

The Group Sails for the “Promised Land”

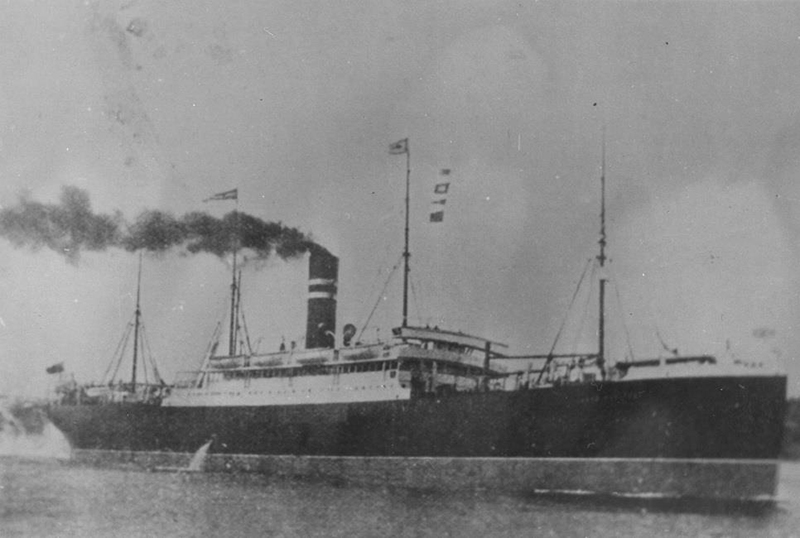

The colonists were originally to set sail on 25 March 1903 but this was postponed by the shipping company until 31 March. At midnight on 30 March, the train full of colonists steamed from London to Liverpool, where all 1,962 of them boarded SS Lake Manitoba and sailed for Canada. The numbers aboard another ship increased during the trip: on SS Lake Simcoe, which sailed later, some twenty stowaways were discovered and one baby was born.

Credit: Photograph of SS Lake Manitoba, 1901-1920, Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 Collection (DI2013.239.1).

SS Lake Manitoba was a new ship, having been constructed only two years prior to this voyage, but it was not equipped for the number of passengers it carried (it was originally prepared to accommodate about 750). The ship was also insufficiently staffed, so the company hired some of the passengers to help the crew. Throughout the voyage there were complaints about the food, drinking water, poor ventilation, and - unsurprisingly - overcrowding. There were reportedly “scuffles among the men” along with some accidents, such as a man who fell down a flight of stairs and broke his leg.[30]

Credit: Saskatoon Public Library, Hillyard Photographs Collection, item B-2099. Photo courtesy of Saskatoon Public Library. It is possible this photo was taken by Frank Henbrow-Smith; see “Transcript of Mr. F. Hembrow-Smith’s Diaries,” 12.

The forward hold had been converted into steerage accommodations by the addition of wooden bunk beds, equipped with straw mattresses but no bedding. All but 300 passengers were in steerage; one remembered discovering that the “snow-white paint on the woodwork turned out to be merely whitewash, and, when the vessel received a smart smack from a wave, large flakes of it fell off along with the dried undercoat of manure.” Seasickness was common – another colonist recalled laying on his bunk and suffering, while

those who had recovered would lean out of their bunks to read in the dim light. They soon learned, however, to pull their heads back in a hurry when a seasick mate in an upper bunk shouted ‘DUCK!’

Although there was little the passengers could do to calm their stomachs, Lloyd worked hard to calm their minds. Every morning and afternoon he gave a series of lectures on what to expect in Canada, followed by a question-and-answer period. And every evening, he held religious services in steerage. The passengers also organized some amusements for themselves, such as a concert, a boxing competition, and a baby beauty contest.[31]

The ship arrived in Saint John, New Brunswick on Good Friday - the exact day that Lloyd had first visited the country in 1881, some 22 years before. Unfortunately, this meant no unloading crews were available on account of the holiday. The vessel sat anchored off the coast, waiting for a berth, as its unhappy passengers fumed. Still, there was plenty to do: during the delay, the passengers exchanged currency and had their health inspections. The latter included an inspection to ensure that the immigrants had been vaccinated against smallpox, which left a small scar. But this inspection was not overly stringent: one colonist observed that passengers who did not have the required vaccination made a mark by pressing a coin hard against their bare arm before the doctor examined them. One recalled that he could not find his mark and simply gestured to the area on his arm where it should have appeared. He was cleared and only later did he realize that he had shown the wrong arm.[32]

The Overland Trip Begins

The ship finally docked early Sunday morning and the colonists then boarded the four trains that awaited them, with their baggage to follow on a later train. Many of the colonists found the train trip unsatisfactory, with its slow speed, frequent stops to let other trains pass, and - for most passengers - the spartan and uncomfortable accommodations. There were two types of cars, Tourist and Colonist. The Tourist cars had pillows, bedding, and curtains. The Colonist cars, however, were bare. One colonist recorded his impressions of them:

The entire coach seated eighty-four passengers. At night, the seat pulled together forming a sleeping place for two persons and the roof portion above pulled down making another berth for two … At the end of each coach was a small apartment furnished with a stove for heating water and warming up food. Wash rooms and lavatories for both men and women were also provided. There were no mattresses for the berths and no privacy if you wished to undress when going to bed. It was rather embarrassing the first night, but after that the women either erected a blanket or pinned up sheets of paper. This method of travelling was quite novel to most of us but we soon got accustomed to it.[33]

Whether or not it would be novel depended on which of Barr’s pamphlets the colonists had read and remembered. In the first, he promised that both types of train cars would provide both comfortable sleeping accommodations and “absolute privacy.” However, in the second he admitted the Colonist cars were not all that comfortable and advised settlers to bring “pillows, blankets (a good supply), drop curtains with safety pins to fasten them to be suspended in front of the berths, soap and towels,” adding that straw mattresses had to be rented from the railway. Those who did not obtain a mattress soon regretted it, though some found novel solutions.

The rolling and jolting of the coach appears always more trying at night, more especially so [for me] in the upper berth. I have discovered a way to pad my hips to save them from getting too sore. Before leaving the boat I changed what money I carried with me into Canadian currency and being late in doing so I could only get dollar bills. These I stuffed into the pockets of a money belt round my waist but have felt rather embarrassed at my rotund appearance during the day but at night by lowering the belt they made a good cushion beneath my hips and the hard Canadian timber beneath.

In retrospect, aside from being crowded, the Barr Colonists “probably did not suffer much more than the average Canadian railway passenger of the time.”[34]

Credit: Canadian Railroad Historical Association (CRHA)/Exporail, the Canadian Railway Museum; Canadian Pacific Railway fonds; P170/NS-12968. Thanks to Exporail for permission to reproduce this photograph here.

Those travelling aboard “The Kennels,” as the train with one or two boxcars filled with 150 dogs became known, were subjected to the noise of the animals barking, howling, and fighting for the duration of the trip.[35] Among the humans, the trip was marked by a few more fights and another birth and death, with the arrival of a new baby and the passing of one colonist who fell between the still-moving train and a station platform, later succumbing to his injuries.[36]

One trainload of four hundred people, mainly young men who did not have sufficient capital and knowledge of farming to begin at the settlement, headed only as far as Winnipeg. There they disembarked and went to work for other farmers, hoping to gain enough experience and money to eventually strike out on their own. The few women of this group primarily sought employment as domestics, also hoping to save enough money to begin a new life.[37]

The rest of the group continued on their train voyage. When they stopped in Regina, a crowd had gathered to greet them and sang “The Maple Leaf Forever.” The colonists replied by singing some popular English songs. And, when the train was departing, the two groups sang “O Canada” together.[38]

Conclusion

At the turn of the twentieth century, two Anglican ministers – keen to play an active role in the British colonization of Canada – convinced nearly 2,000 English people to leave their old lives behind and begin anew in Canada. Few were farmers, many were veterans of the Boer War disillusioned with life in England, but all chose to put their faith in the plans of Isaac Barr. Barr was a dreamer who did not set a limit on how many could participate and quickly became overwhelmed by the numbers involved, leading the Canadian government to make their own plans to ensure the colonists wellbeing in order to prevent negative publicity.

Despite the chaotic preparations, the colonists arrived in Canada in April 1903. They were safe and sound, but already discouraged by the discomfort of the voyage. These feelings would only grow as they traveled across the country by train. Once they arrived at their reserved land, did this group, with so little farming experience, succeed at planting crops and establishing homesteads? Find out in Part II of this paper.

- Isaac Barr, letter to colonists, quoted in Lynne Bowen, Muddling Through: The Remarkable Story of the Barr Colonists (Vancouver and Toronto: Greystone Books [Douglas & McIntyre], 1992), 53.↩

- Though it should be noted that wealthier Britons from urban settings were viewed with skepticism. For a helpful overview, see Joy Parr’s review article, “The Significance of Gender Among Emigrant Gentlefolk,” Dalhousie Review 62, no. 4 (Winter 1982-83): 693–9.↩

- On block settlements (frequently spelled “bloc”), see Alan Anderson, “Ethnic Bloc Settlements,” Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan (2007).↩

- On the territory prior to the twentieth century, see Wade Leslie Dargin, “The 18th and 19th Century Cree Landscape of West Central Saskatchewan: Implications for Archaeology” (MA thesis, University of Saskatchewan, 2004).↩

- On Treaty 6, see J.R. Miller, Compact, Contract, Covenant: Aboriginal Treaty-Making in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009), chapter six; Arthur J. Ray, Jim Miller, and Frank Tough, Bounty and Benevolence: A History of Saskatchewan Treaties (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2000), chapter nine (quote on 146); and James Daschuk, Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life (Regina: University of Regina Press, 2013), esp. 96–8 and 123 (withholding of rations).↩

- See Honour Bound: Onion Lake and the Spirit of Treaty Six: The International Validity of Treaties with Indigenous Peoples, International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, Document No. 84 (Copenhagen, Denmark: IWGIA, 1997); Christian Thompson, “Onion Lake First Nation,” Indigenous Saskatchewan Encyclopedia; and Sylvie Marceau-Kozicki, “Onion Lake Indian Residential Schools, 1892-1943” (MA thesis, University of Saskatchewan, 1993), chapter two.↩

- Helen Evans Reid, All Silent, All Damned: The Search for Isaac Barr (Toronto: Ryerson, 1969), 19.↩

- Reid, All Silent, All Damned, 27–35.↩

- Rhodes was an “arch imperialist” whose callousness made him controversial even in his lifetime. His “British South Africa Company” invaded and occupied what become known as Rhodesia (or much of what are now the countries of Zambia and Zimbabwe); thousands of African soldiers perished in these battles and there were subsequently “brutal suppressions of people on their own land.” See William Beinart, “Rhodes Must Fall: The Uses of Historical Evidence in the Statue Debate in Oxford, 2015–6,” Oxford and Empire Network (October 2019).↩

- Reid, All Silent, All Damned, 39–45; and Eric Holmgren, “Isaac M. Barr and the Britannia Colony” (MA thesis, University of Alberta, 1964) 24.↩

- Bowen, Muddling Through, 11.↩

- Bowen, Muddling Through, 9-13.↩

- Chris Kitzan, “The Fighting Bishop: George Exton Lloyd and the Immigration Debate” (MA thesis, University of Saskatchewan, 1996),” 9.↩

- Kitzan, “Fighting Bishop,” 9–12. Lloyd was awarded a North-West Field Force medal with clasp and, according to Reid, All Silent, All Damned, 113, he was also recommended for the Victoria Cross. Details of the conflict, otherwise known as Battle of Cut Knife, are debated to this day. In Lloyd’s mind, however, the uprising represented a direct attack on British authority, law, and order, the end result was that “the Indian learned that he could not buck the white man and so settled down to the new conditions” (Kitzan, “Fighting Bishop,” 10). Lloyd’s actions can be seen in keeping with a longer tradition of settler colonial vigilante violence, discussed in such works as Tyler Shipley, Canada in the World: Settler Capitalism and the Colonial Imagination (Halifax: Fernwood Publishing, 2020). On the North-West Resistance/Rebellion, see also Miller, Skyscrapers Hide the Heavens, chapter ten.↩

- The exact nature of the controversy is not clear, but his letter of resignation admitted that he had alienated at least three individuals, all of whom were making his job difficult; see Kitzan, “Fighting Bishop,” 13–15 and 15n35.↩

- Kitzan, “Fighting Bishop,” 13–16. On the CCCS, see Hilary M. Carey, God’s Empire: Religion and Colonialism in the British World, c.1801-1908 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), chap. five and, on the Barr Colony, 366–68.↩

- Kitzan, “Fighting Bishop,” 16–17; and Bowen, Muddling Through, 13–14.↩

- Holmgren, “Barr and the Britannia Colony,” 28; and Bowen, Muddling Through, 12 (“misleading”). The pamphlet is reproduced in J[ames] Hanna McCormick, Lloydminster, or, 5000 Miles with the Barr Colonists (London: Dranes, 1924), 21–35.↩

- Reid, All Silent, All Damned, 52–3. According to Bowen, Muddling Through, 24, Lloyd’s office received up to 50 letters per day.↩

- Acting Commissioner [C.F. Just], letter to Rev. J.N. Barr [sic], 30 August 1902, RG76B, Subject, policy and case files in the First Central Registry series of the Immigration Program, 1892-1950, reel C-7403, Library and Archives Canada (hereafter LAC). As Holmgren, “Barr and the Britannia Colony,” put it: “In his readiness to pursue his plans to the utmost, Barr revealed a way of capitalizing on verbal promises from [the Commissioner of Immigration] and others (even though these may not have been very firm) and of committing these men in print and so embarrassing them into agreeing with him. In this way … Barr’s conduct verged on indiscreet and … may have antagonized others.”↩

- See for instance James A. Smart, letter to Barr, 26 February 1903, RG76B, Subject, policy and case files in the First Central Registry series of the Immigration Program, 1892-1950, reel C-7403, LAC. Despite the similar terminology, land reserved for European settlers should not be confused with First Nations reserves, which were administered completely differently.↩

- Holmgren, “Barr and the Britannia Colony,” 44 and 47; and E.H. Oliver, “Coming of the Barr Colonists: The ‘All British’ Colony that Became Lloydminster,” Canadian Historical Association Annual Report (1926), 74. Sources give differing accounts of the distance but all range between 241–321 kilometers; it is approximately 270 kilometers by modern highway.↩

- Holmgren, “Barr and the Britannia Colony,” 48 and 53.↩

- Holmgren, “Barr and the Britannia Colony,” 52–53; Reid, All Silent, All Damned, 47 (“sires”); and McCormick, Lloydminster, 37 (“Hempire [sic]”).↩

- Holmgren, “Barr and the Britannia Colony,” 58–63 and 76–7.↩

- Holmgren, “Barr and the Britannia Colony,” 67–70. He further suggests failure of the syndicates may have been due to a lack of subscriptions being sold, which would have in turn left Barr with insufficient funds to purchase adequate supplies (71–76, see also 80).↩

- “Transcription of M. F. Hembrow-Smith’s Diaries,” 6. The latter is held by the Museum of Western Development (Saskatoon), and I would like to thank them for making a copy available to me.↩

- Holmgren, “Barr and the Britannia Colony,” 77, 79, 80, and 90; Lucina Rasmussen, “Empire, Identity, and the Britannia Colony: Female Settlers’ Perspectives on Life in Western Canada” (MA thesis, University of Alberta, 2006), 105; and Bowen, Muddling Through, 64.↩

- Ivany, “An Ethnic Experience,” 39 and 58 (ages and occupations of colonists); Holmgren, “Barr and the Britannia Colony,” 132 (“great majority”); and, for the doctor’s account, Oliver, “Coming of the Barr Colonists,” 69; and Bowen, Muddling Through, 94.↩

- On the vessel, see “Lake Manitoba,” Tyne Built Ships, which states it was originally built to accommodate 122 in first class, 130 in second, and 500 in third; sometime after this voyage the ship would be refitted to transport 150 passengers in cabins and an additional 1,000 in steerage. On the voyage, see Bowen, Muddling Through, 51–68 and 111; Keith Foster, “The Barr Colonists: Their Arrival and Impact on the Canadian North-West,” Saskatchewan History 35, no. 3 (1982), 84–5; Holmgren, “Barr and the Britannia Colony,” 85–7; and Reid, All Silent, All Damned, 5 and 59–68. The anecdote about the birth and the stowaways is from Alice Rendell, quoted in Oliver, “Coming of the Barr Colonists,” 76.↩

- Foster, “The Barr Colonists,” 85 (both quotes); Bowen, Muddling Through, 54 (“all but 300”); Reid, All Silent, All Damned, 62 (on Lloyd’s lectures); and “Transcript of Mr. F. Hembrow-Smith’s Diaries,” 13–14 (on amusements). For the sailing schedule, see here.↩

- Reid, All Silent, All Damned, 64; and “Transcript of Mr. F. Hembrow-Smith’s Diaries,” 14.↩

- “Transcript of Mr. F. Hembrow-Smith’s Diaries,” 14.↩

- First pamphlet reproduced in McCormick, Lloydminster, 27; the second quoted in Reid, All Silent, All Damned, 51; and Foster, “The Barr Colonists,” 87.↩

- Reid, “Clerical Con Man,” 40, asserted that the dogs were thrown overboard during the sea voyage, but this erroneous claim disappeared from her subsequent book, All Silent, All Damned, 61 (but not before it was repeated in Foster, “The Barr Colonists,” 85). Bowen, Muddling Through, 69–70, reports that each of the trains had a dog car, while the report that there were two cars full of dogs and that the train was called “the Kennel” appears only in “Transcript of Mr. F. Hembrow-Smith’s Diaries,” 14.↩

- Reid, All Silent, All Damned, 68–9; Rendell in Oliver, “Coming of the Barr Colonists,” 76–7; and Holmgren, “Barr and the Britannia Colony,” 88.↩

- Bowen, Muddling Through, 81; and “Transcript of Mr. F. Hembrow-Smith’s Diaries.”↩

- “Transcript of Mr. F. Hembrow-Smith’s Diaries,” 18.↩